Nine Stones Close

Nine Stones Close, also known as the Grey Ladies, is a stone circle on Harthill Moor in Derbyshire in the English East Midlands. It is part of a tradition of stone circle construction that spread throughout much of Britain, Ireland, and Brittany during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages, over a period between 3300 and 900 BCE. The purpose of the monument is unknown.

| |

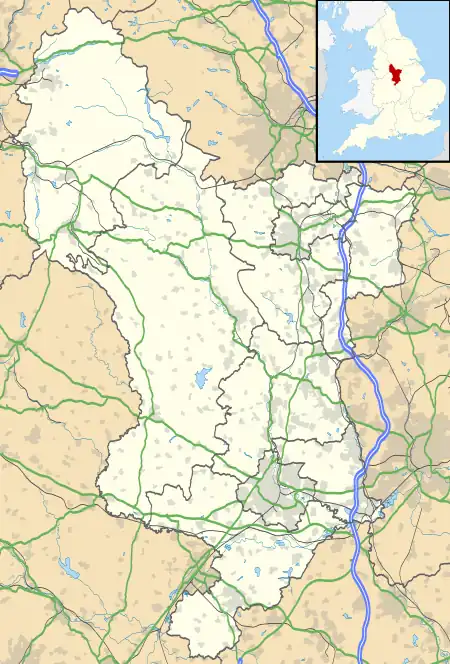

Location in Derbyshire | |

| Location | Derbyshire |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53°09′38″N 1°39′52″W |

| Type | Stone circle |

| History | |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

The Nine Stones Close originally measured 13.7 metres in diameter. In the mid-19th century it had seven stones in its ring, although by the early 21st century that number had declined to four. There are two carved cup marks, a form of rock art, evident on one of the remaining stones.There may have previously been at earthen tumulus inside the ring, suggested by a slight elevation observed in the mid-19th century. It is possible that the ring was deliberately positioned to allow sightlines to the nearby Robin Hood's Stride, a gritstone crag, and that a nearby sandstone boulder decorated with cup markings also had reference to the circle.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Nine Ladies attracted the attention of antiquarians like Hayman Rooke and Thomas Bateman. In 1877 the antiquarians William Greenwell and Llewellynn Jewitt excavated at the site, while in the late 1930s the Derbyshire Archaeological Society set two of the orthostats standing again.

Location

Nine Stones Close is located on Harthill Moor in Derbyshire.[1] It is located 1½ miles southeast of Youlgreave.[2] Less than 400m to the south-southwest of the stone circle is Robin Hood's Stride, a natural gritsone crag.[1] Harthill Moor itself also has a range of other archaeological features, including Bronze Age barrows and settlement enclosures.[3]

Context

While the transition from the Early Neolithic to the Late Neolithic in the fourth and third millennia BCE saw much economic and technological continuity, there was a considerable change in the style of monuments erected, particularly in what is now southern and eastern England.[4] By 3000 BCE, the long barrows, causewayed enclosures, and cursuses that had predominated in the Early Neolithic were no longer built, and had been replaced by circular monuments of various kinds.[4] These include earthen henges, timber circles, and stone circles.[5] Stone circles exist in most areas of Britain where stone is available, with the exception of the island's south-eastern corner.[6] They are most densely concentrated in south-western Britain and on the north-eastern horn of Scotland, near Aberdeen.[6] The tradition of their construction may have lasted 2,400 years, from 3300 to 900 BCE, the major phase of building taking place between 3000 and 1300 BCE.[7]

These stone circles typically show very little evidence of human visitation during the period immediately following their creation.[8] The historian Ronald Hutton noted that this suggests that they were not sites used for rituals that left archaeologically visible evidence, but may have been deliberately left as "silent and empty monuments".[9] The archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson argues that in Neolithic Britain, stone was associated with the dead, and wood with the living.[10] Other archaeologists have proposed that the stones might not represent ancestors, but rather other supernatural entities, such as deities.[9]

Across eastern Britain—including the East Midlands—stone circles are far less common than in the west of the island, possibly due to the general scarcity of naturally occurring stone here. There is much evidence for timber circles and earthen henges in the east, suggesting that these might have been more common than their stone counterparts.[11] In the area of modern Derbyshire, there are five or six known stone circles although the remains of many ring-cairns, a different style of prehistoric monument, are also common and can look much like the stone rings.[12] Stylistically, those found in this county are similar to those found in Yorkshire.[12] Within the Peak District, nine was frequently favoured as the number of stones used in a circle, as suggested by names like the Nine Stones Close and Nine Ladies.[13] The only large stone circles in the Peak are Arbor Low and The Bull Ring, both monuments which combine a stone circle with an earthen henge and which are located on the sandstone layers.[13] There are also a few smaller stone circles, such as Doll Tor and the Nine Stones Close, that are close to the limestone edge.[14]

Design, construction, and use

The circle once measured 13.7 metres in diameter.[2] As of 1847, there were seven stones recorded as part of the circle,[2] although by the early 21st century only four remained.[2][15] These are among the largest to be found in any stone circle in Derbyshire.[16] The archaeologists Graeme Guilbert, Daryl Garton, and David Walters described these as an "imposing group,"[17] while Burl characterised the monument as an "impressive site".[2] One of the stones was removed in the 18th century and is now used as an oversized field gatepost nearby.[15] Another long, prostrate stone lies in a field 230 metres to the north-west.[2]

The stones in the circle range from 1.2m in height to 2.1m in height, the tallest standing at the southern side of the ring.[2] Two of the remaining upright stones are now set in concrete bases.[2] Two of them have fluting on their tops, caused by longstanding weathering, although whether this occurred prior to their inclusion in the circle is unknown.[18] The southernmost orthostat in the circle contains two weathered cup marks on its southern face.[19] It is unclear if these cup marks were carved into the rock prior to it being incorporated into the stone circle or after.[20]

The precise date of Nine Stones Close is not known.[19] The large size of the stones used, in contrast to those at other stone circles in Derbyshire, had resulted in suggestions that it might be earlier than the others, having been created in the Neolithic period.[19] Excavations in 1847, 1877 and 1939 found flints and pot-sherds dating from the Bronze Age.[15]

From the stone circle, at midsummer the major southern moon can be seen setting between the two boulders of the nearby Robin Hood's Stride.[16] Burl suggested that this alignment may have been the reason for the deliberate placement of the circle.[2] It is also possible that the distinctive shape of Robin Hood's Stride was itself caused by human alteration of the natural feature.[21] A sandstone boulder lying 130m to the north/northeast of Nine Stones Close contains a row of three carved cup marks, one of which is partially enclosed by a ring. This is an example of the cup-and-ring style of rock art, which is typically regarded as being Neolithic or Early Bronze Age in date.[22] The intended meanings of this rock art, as elsewhere in Britain, are unclear.[23] Harthill Moor was also home to various tumuli, or earthen mounds, traces of some of which remain visible in the early 21st century.[23] A range of prehistoric artefacts, including food vessels, stone axes, a macehead, an axe-hammer, and a bronze flat axe have been found on Harthill Moor, often as chance discoveries.[24]

Modern history

The antiquarian Hayman Rooke noted the existence of the Nine Stones Close, which he called a "Druid temple," in a 1782 article about the heritage of Stanton and Harthill Moors published in the journal Archaeologia. At that point he observed six stones in the ring.[25] The idea that Britain's prehistoric monuments had been built by the druids, ritual specialists present in parts of Iron Age Western Europe, was one that had attracted broad support among antiquarians over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, having been adopted by influential writers such as John Aubrey and William Stukeley.[26]

This idea was repeated by the antiquarian Thomas Bateman in his 1848 book Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire, where he referred to "Nine-stone Close" as a "small druidical cirque."[27] Bateman observed seven stones in the circle and a slight elevation in the centre, "so as to appear as a low tumulus", suggesting the possibility that this had once been used for burials.[27] Bateman also commented on the presence of two monoliths standing erect about 80 yards south of the stone circle.[27] In 1847, Bateman had dug at the site, discovering "several fragments of imperfectly baked pottery accompanied by flint both in a natural and calcinated state."[2]

In 1877, William Greenwell and Llewellyn Jewitt excavated at the site.[28] Their trenches were located at the base of the second highest stone and in the centre of the circle, although produced no finds.[2] The Nine Stones Close were subsequently referenced, although not by name, in J. Ward's contribution on "Early Man" in the Victoria County History volume on Derbyshire, published in 1905. Ward described the ring as possessing "six upright stones of large size."[29]

In 1936, one of the stones in the circle fell over. The Derbyshire Archaeological Society decided to re-erect both this stone and another, which they believed had lain largely recumbent for centuries.[30] In seeking advice for this project, they turned to Alexander Keiller, known for his work at the stone circle at Avebury in Wiltshire.[31] During this reconstruction, these two fallen stones were set in concrete bases to keep them upright.[32]

Folklore

The site is also named the Grey Ladies.[33] Burl noted folklore that these stones were supposed to dance both at midnight and at midday.[2] In 1947, Heathcote suggested that this was not an example of folklore emerging from within the oral culture of the local community, but rather had been invented by "early guidebook writers".[34]

It is uncertain whether there were originally nine stones, one theory being that nine is a corruption of 'noon', said to be the time when, according to local folklore, fairies would gather at the site to dance.[35]

References

Footnotes

- Burl 2005, p. 53; Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 12.

- Burl 2005, p. 53.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 12; Historic England 1993.

- Hutton 2013, p. 81.

- Hutton 2013, pp. 91–94.

- Hutton 2013, p. 94.

- Burl 2000, p. 13.

- Hutton 2013, p. 97.

- Hutton 2013, p. 98.

- Hutton 2013, pp. 97–98.

- Burl 2000, pp. 283–284.

- Burl 2000, p. 297.

- Burl 2000, p. 298.

- Burl 2000, pp. 289–290.

- Historic England 1993.

- Burl 2000, p. 299; Burl 2005, p. 53.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 12.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 21.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 20.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, pp. 20–21.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, pp. 21–22.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, pp. 12–14, 16.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 26.

- Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2006, p. 25.

- Rooke 1782, p. 113.

- Hutton 2009, pp. 14–15.

- Bateman 1848, p. 111.

- Heathcote 1939, p. 126; Burl 2005, p. 53.

- Ward 1905, p. 183.

- Heathcote 1939, p. 126.

- Heathcote 1939, p. 128.

- Heathcote 1939, p. 127.

- Grinsell 1976, p. 159; Burl 2005, p. 53.

- Grinsell 1976, p. 159.

- Hamilton, Dave (2019). Wild Ruins BC. Bath: Wild Things Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 978-1910636169.

Bibliography

- Bateman, Thomas (1848). Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire. London: John Russell Smith.

- Burl, Aubrey (2000). The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08347-7.

- Burl, Aubrey (2005). A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11406-5.

- Grinsell, Leslie V. (1976). Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7241-6.

- Guilbert, Graeme; Garton, Daryl; Walters, David (2006). "Prehistoric Cup-and-Ring Art at the Heart of Harthill Moor". Derbyshire Archaeological Journal. 126: 12–30.

- Heathcote, J. P. (1939). "The Nine Stones, Harthill Moor" (PDF). Derbyshire Archaeological Journal. 60: 126–128.

- Historic England (1 December 1993). "Nine Stone Close small stone circle (1008007)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hutton, Ronald (2009). "Megaliths and Memory". In Joanne Parker (ed.). Written on Stone: The Cultural Reception of British Prehistoric Monuments. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 10–22. ISBN 978-1-4438-1338-9.

- Hutton, Ronald (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19771-6.

- Rooke, Hayman (1782). "An Account of Some Druidical Remains on Stanton and Hartle Moor in the Peak, Derbyshire". Archaeologia. 6: 110–115. doi:10.1017/S0261340900020130.

- Ward, J. (1905). "Early Man". In William Page (ed.). The Victoria History of the County of Derby: Volume I. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 159–190.

Further reading

- Barnatt, John (1978). Stone Circles of the Peak. London: Turnstone Books. ISBN 978-0855000882.

- Barnatt, John (1987). "Bronze Age Settlement on the East Moors of the Peak District of Derbyshire and South Yorkshire". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 53: 393–418. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00006307. S2CID 130330745.

- Barnatt, John (1990). The Henges, Stone Circles and Ringcairns of the Peak District. Sheffield Archaeological Monographs I. Sheffield: J. R. Collis Publications. ISBN 978-0906090343.

- Barnatt, J. and Robinson, F. (2003) Prehistoric rock-art at Ashover School and further new discoveries elsewhere in the Peak District' DAJ 123: l-28'

- Goss, W. 1889. The Life and Death of Llewellynn Jewitt. London: Henry Gray.

- Heathcote, J. Percy, Birchover – Its Prehistoric and Druidical Remains, Wilfrid Edwards: Chesterfield 1947

External links

![]() Media related to Nine Stones, Derbyshire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nine Stones, Derbyshire at Wikimedia Commons