Nipple

The nipple is a raised region of tissue on the surface of the breast from which, in females, milk leaves the breast through the lactiferous ducts to feed an infant.[1][2] The milk can flow through the nipple passively or it can be ejected by smooth muscle contractions that occur along with the ductal system. Male mammals also have nipples but without the same level of function, and often surrounded by body hair.

| Nipple | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Part of | Breast |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | papilla mammaria |

| MeSH | D009558 |

| TA98 | A16.0.02.004 |

| TA2 | 7105 |

| FMA | 67771 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The nipple is surrounded by the areola, which is often a darker colour than the surrounding skin.[3] A nipple is often called a teat when referring to non-humans. "Nipple" or "teat" can also be used to describe the flexible mouthpiece of a baby bottle. In humans, the nipples of both males and females can be stimulated as part of sexual arousal. In many cultures, human female nipples are sexualized,[4] or regarded as sex objects and evaluated in terms of their physical characteristics and sexiness.[5] Some cultures have little to no sexualization of the nipple, and going topless presents no barrier.

Anatomy

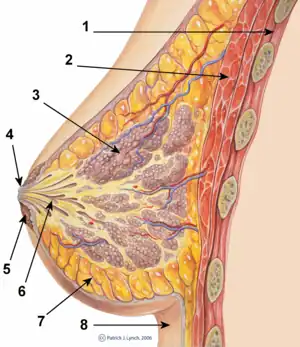

In mammals, a nipple (also called mammary papilla or teat) is a small projection of skin containing the outlets for 15–20 lactiferous ducts arranged cylindrically around the tip. Marsupials and eutherian mammals typically have an even number of nipples arranged bilaterally, from as few as 2 to as many as 19.[6]

The skin of the nipple is rich in a supply of special nerves that are sensitive to certain stimuli: these are slowly-adapting and rapidly-adapting cutaneous mechanoreceptors. Mechanoreceptors are identified respectively by Type I slowly-adapting with multiple Merkel corpuscle end-organs and Type II slowly-adapting with single Ruffini corpuscle end-organs, as well as Type I rapidly-adapting with multiple Meissner corpuscle end-organs and Type II rapidly-adapting with single Pacinian corpuscle end-organs. The dominant nerve supply to the nipple comes from the lateral cutaneous branches of fourth intercostal nerve.[7] The nipple is also used as an anatomical landmark. It marks the T4 (fourth thoracic vertebra) dermatome and rests over the approximate level of the diaphragm.[8]

The arterial supply to the nipple and breast originates from the anterior intercostal branches of the internal thoracic (mammary) arteries; lateral thoracic artery; and thoracodorsal arteries. The venous vessels parallel the arteries.[2] The lymphatic ducts that drain the nipple are the same for the breast.[2] The axillary nodes are the apical axillary nodes, the lateral group and the anterior group.[9] 75% of the lymph is drained through the axillary lymph nodes located near the armpit. The rest of the drainage leaves the nipple and breast through infroclavicular, pectoral, or parasternal nodes.

Since nipples change throughout the life span in men and women, the anatomy of the nipple can change and this change may be expected and considered normal.

In male mammals

Almost all mammals have nipples. Why males have nipples has been the subject of scientific research. Differences among the sexes (called sexual dimorphism) within a given species are considered by evolutionary biologists to be mostly the result of sexual selection, directly or indirectly. There is a consensus that the male nipple exists because there is no particular advantage to males losing the trait (this is called a spandrel).[10][11][12]

Function

The physiological purpose of nipples is to deliver milk, produced in the female mammary glands during lactation, to an infant. During breastfeeding, nipple stimulation by an infant will stimulate the release of oxytocin from the hypothalamus. Oxytocin is a hormone that increases during pregnancy and acts on the breast to help produce the milk-ejection reflex. Oxytocin release from the nipple stimulation of the infant causes the uterus to contract even after childbirth.[13][14] The strong uterine contractions that are caused by the stimulation of the mother's nipples help the uterus contract to clamp down the uterine arteries. These contractions are necessary to prevent post-partum haemorrhage.[15]

When the infant suckles or stimulates the nipple, oxytocin levels rise and small muscles in the breast contract, moving the milk through the milk ducts. The result of nipple stimulation by the infant helps to move breast milk out through the ducts and to the nipple. This contraction of milk is called the "let-down reflex".[16] Latching on refers to the infant fastening onto the nipple to breastfeed. A good attachment is when the bottom of the areola (the area around the nipple) is in the infant's mouth and the nipple is drawn back inside his or her mouth. A poor latch results in insufficient nipple stimulation to create the let down reflex. The nipple is poorly stimulated when the baby latches on too close to the tip of the nipple. This poor attachment can cause sore and cracked nipples and a reluctance of the mother to continue to breastfeed.[17][18] After birth, the milk supply increases based upon the continuous and increasing stimulation of the nipple by the infant. If the baby increases nursing time at the nipple, the mammary glands respond to this stimulation by increasing milk production.

Clinical significance

Pain

Nipple pain can be a disincentive for breastfeeding.[19] Sore nipples that progress to cracked nipples is of concern since many women cease breastfeeding due to the pain. In some instances, an ulcer will form on the nipple.[20] One reason for the development of cracked and sore nipples is the incorrect latching-on of the infant to the nipple. If a nipple appears to be wedge-shaped, white and flattened, this may indicate that the attachment of the infant is not good and there is a potential of developing cracked nipples.[21] Herpes infection of the nipple is painful.[22] Nipple pain can also be caused by excessive friction of clothing against the nipple that causes a fissure.

Discharge

Nipple discharge refers to any fluid that seeps out of the nipple of the breast. Discharge from the nipple does not occur in lactating women. And discharge in non-pregnant women or women who are not breastfeeding may not cause concern. Men that have discharge from their nipples are not typical. Discharge from the nipples of men or boys may indicate a problem. Discharge from the nipples can appear without squeezing or may only be noticeable if the nipples are squeezed. One nipple can have discharge while the other does not. The discharge can be clear, green, bloody, brown or straw-coloured. The consistency can be thick, thin, sticky or watery.[23][24]

Some cases of nipple discharge will clear on their own without treatment. Nipple discharge is most often not cancer (benign), but rarely, it can be a sign of breast cancer. It is important to determine what is causing the discharge and to get treatment. Reasons for nipple discharge include:[23]

- Pregnancy

- Recent breastfeeding

- Rubbing on the area from a bra or T-shirt

- Injury to the breast

- Infection

- Inflammation and clogging of the breast ducts

- Noncancerous pituitary tumors

- Small growth in the breast (usually not cancer)

- Severe underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism)

- Fibrocystic breast (normal lumpiness in the breast)

- Use of certain medicines

- Use of certain herbs, such as anise and fennel

- Widening of the milk ducts[23]

Sometimes, babies can have nipple discharge. This is caused by hormones from the mother before birth. It usually goes away in two weeks. Cancers such as Paget's disease (a rare type of cancer involving the skin of the nipple) can also cause nipple discharge.[23]

Nipple discharge that is not normal is bloody, comes from only one nipple, or comes out on its own without squeezing or touching the nipple. Nipple discharge is more likely to be normal if it comes out of both nipples or happens when the nipples are squeezed. Squeezing the nipple to check for discharge can make it worse. Leaving the nipple alone may make the discharge stop.[23]

Nipple discharge in a male is usually of more concern. Most of the time a mammogram and an examination of the fluid is done. A biopsy is often performed. A fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy can be fast and least painful. A very thin, hollow needle and slight suction will be used to remove a small sample from under the nipple. Using a local anesthetic to numb the skin may not be necessary since a thin needle is used for the biopsy. Receiving an injection to prevent pain from the biopsy may be more painful than the biopsy itself.[25]

Some men develop a condition known as gynecomastia, in which the breast tissue under the nipple develops and grows. Discharge from the nipple can occur. The nipple may swell in some men possibly due to increased levels of estrogen.[26]

Appearance

.jpg.webp)

Changes in appearance may be normal or related to disease.

- Inverted nipples – This is normal if the nipples have always been indented inward and can easily point out when touched. If the nipples are pointing in and this is new, this is an unexpected change.

- Skin puckering of the nipple – This can be caused by scar tissue from surgery or an infection. Often, scar tissue forms for no reason. Most of the time this issue does not need treatment. This is an unexpected change. This change can be of concern since puckering or retraction of the nipple can indicate an underlying change in breast tissue that may be cancerous.[27]

- The nipple is warm to the touch, red or painful – This can be an infection. It is rarely due to breast cancer.

- Scaly, flaking, or itchy nipple – This is most often due to eczema or a bacterial or fungal infection. This change is not expected. Flaking, scaly, or itchy nipples can be a sign of Paget's disease.

- Thickened skin with large pores – This is called peau d'orange because the skin looks like an orange peel. An infection in the breast or inflammatory breast cancer can cause this problem. This is not an expected change.

- Retracted nipples – The nipple was raised above the surface but changes, begins to pull inward, and does not come out when stimulated.[28]

The average projection and size of human female nipples is slightly more than 3⁄8 inch (9.5 mm).[29]

Breast cancer

Symptoms of breast cancer can often be seen first by changes of the nipple and areola, although not all women have the same symptoms, and some people do not have any signs or symptoms at all. A person may find out they have breast cancer after a routine mammogram. Warning signs can include:[30][31]

- New lump in the nipple, or breast or armpit

- Thickening or swelling of part of the breast, areola, or nipple

- Irritation or dimpling of breast skin

- Redness or flaky skin in the nipple area or the breast

- Pulling in of the nipple or pain in the nipple area

- Nipple discharge other than breast milk, including blood

- Any change in the size or the shape of the breast or nipple

- Pain in any area of the breast[30][31]

Changes in the nipple are not necessarily symptoms or signs of breast cancer. Other conditions of the nipple can mimic the signs and symptoms of breast cancer.[30]

Vertical transmission

Some infections are transmitted through the nipple, especially if irritation or injury to the nipple has occurred. In these circumstances, the nipple itself can become infected with Candida that is present in the mouth of the breastfeeding infant. The infant will transmit the infection to the mother. Most of the time, this infection is localized to the area of the nipple. In some cases, the infection can progress to become a full-blown case of mastitis or breast infection.[32] In some cases, if the mother has an infection with no nipple cracks or ulcerations, it is still safe to breastfeed the infant.

Herpes infection of the nipple can go unnoticed because the lesions are small but usually are quite painful. Herpes in the newborn is a serious and sometimes fatal infection.[22] Transmission of Hepatitis C and B to the infant can occur if the nipples are cracked.[33]

Other infections can be transmitted through a break of the skin of the nipple and can infect the infant.

Other disorders

- Nipple bleb

- Candida infection of the nipple

- Eczema of the nipple

- Inverted nipple

- Staphylococcus infection of the nipple

- Edematous areola[34]

- Herpes infection of the nipple

- Reynaud phenomenon of the nipple[22]

- Flat nipple[35]

Surgery

A nipple-sparing/subcutaneous mastectomy is a surgical procedure where breast tissue is removed, but the nipple and areola are preserved. This procedure was historically done only prophylactically or with mastectomy for the benign disease over the fear of increased cancer development in retained areolar ductal tissue. Recent series suggest that it may be an oncologically sound procedure for tumours not in the subareolar position.[36][37][38]

Society and culture

Exposure

The cultural tendency to hide the female nipple under clothing has existed in Western culture since the 1800s.[4][5][39] As female nipples are often perceived an intimate part, covering them might have originated under Victorian morality as with riding side saddle. Exposing the entire breast and nipple is a form of protest for some and a crime for others.[39][40] The exposure of nipples is usually considered immodest and in some instances is viewed as lewd or indecent behavior.[41]

A case in Erie, Pennsylvania, concerning the exposure of breasts and nipple proceeded to the US Supreme Court.[42] The Erie ordinance was regulating the nipple in public as an act that is committed when a person "knowingly or intentionally, ... appears in a state of nudity commits Public Indecency." Later in the statute, nudity is further described as an uncovered female nipple. But nipple exposure of a man was not regulated. An opinion column credited to Cecil Adams noted: "Ponder the significance of that. A man walks around bare-chested and the worst that happens is he won't get served in restaurants. But a woman who goes topless is legally in the same boat as if she'd had sex in public. That may seem crazy, but in the US it's a permissible law."[40]

The legality around the exposure of nipples is inconsistently regulated throughout the US. Some states do not allow the visualization of any part of the breast. Other jurisdictions prohibit any female chest anatomy by banning anatomical structures that lie below the top of the areola or nipple. Such is the case in West Virginia and Massachusetts. West Virginia's regulation is very specific and is not likely to be misinterpreted, stating: "[The] display of 'any portion of the cleavage of the human female breast exhibited by a dress, blouse, skirt, leotard, bathing suit, or other wearing apparel [is permitted] provided the areola is not exposed, in whole or in part.'"[40]

Instagram has a "no nipples" policy with exceptions: material that is not allowed includes "some photos of female nipples, but photos of post-mastectomy scarring and women actively breastfeeding are allowed. Nudity in photos of paintings and sculptures is OK, too".[43] Previously, Instagram had removed images of nursing mothers. Instagram removed images of Rihanna and had her account cancelled in 2014 when she posted selfies with nipples. This was incentive for the Twitter campaign #FreeTheNipple.[44] In 2016, an Instagram page invited users to post images of nipples from both sexes; @genderless_nipples, which displays close ups of both the nipples of men and women for the purpose of spotlighting what may be inconsistency.[45] Some contributors have circumvented the policy.[46][47] Facebook has also been struggling to define its nipple policy.[45][48][49]

Filmmaker Lina Esco made a film entitled Free the Nipple, which is about "laws against female toplessness or restrictions on images of female, but not male, nipples", which Esco states is an example of sexism in society.[50]

Sexuality

Nipples can be sensitive to touch, and nipple stimulation can incite sexual arousal.[51] Few women report experiencing orgasm from nipple stimulation.[52][53] Before Komisaruk et al.'s functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) research on nipple stimulation in 2011, reports of women achieving orgasm from nipple stimulation relied solely on anecdotal evidence.[54] Komisaruk's study was the first to map the female genitals onto the sensory portion of the brain; it indicates that sensation from the nipples travels to the same part of the brain as sensations from the vagina, clitoris and cervix, and that these reported orgasms are genital orgasms caused by nipple stimulation, and may be directly linked to the genital sensory cortex ("the genital area of the brain").[54][55][56]

Etymology

The word "nipple" most likely originates as a diminutive of neb, an Old English word meaning "beak", "nose", or "face", and which is of Germanic origin.[58] The words "teat" and "tit" share a Germanic ancestor. The second of the two, tit, was inherited directly from Proto-Germanic, while the first entered English via Old French.[59][60]

See also

- Breast milk

- Fleischer's syndrome

- Nip slip

- Nipplegate

- Nipple piercing

- Nipple prosthesis for breast cancer survivors

- Pasties

- Supernumerary (third) nipple

- Udder

References

Citations

- "nipple". Retrieved 4 August 2017 – via The Free Dictionary.

- Hansen 2010, p. 80.

- "nipple". Taber's Online. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Beer, Todd (2015-05-12). "Social Construction of the Body: The Nipple". SOCIOLOGYtoolbox. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- Dewar, Gwen (October 2012). "The sexualization of girls: Is the popular culture harming our kids?". Parenting Science.

- Ramel, Gordon. "Mammalian Milk & Nutritional Profile of the Milk of Various Mammals". Earth Life. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- Grabb & Smith's Plastic Surgery 6th edition. Chapter 59 page 593

- Hansen 2010, p. 73.

- Imwold, Denise (2003). Anatomica's body atlas. San Diego, CA: Laurel Glen. pp. 286–7. ISBN 9781571459237.

- Lawrence, Eleanor (5 August 1999). "Why do men have nipples?". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news990805-1.

- Burke, Anna (July 19, 2017). "Do Male Dogs Have Nipples?". American Kennel Club.

- Simons, Andrew M. (January 13, 2003). "Why do men have nipples?". Scientific American.

- Henry 2016, p. 117.

- "Glossary - womenshealth.gov". womenshealth.gov. 2017-01-10. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Abedi, P; Jahanfar, S; Namvar, F; Lee, J (27 January 2016). "Breastfeeding or nipple stimulation for reducing postpartum haemorrhage in the third stage of labour". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD010845. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010845.pub2. PMC 6718231. PMID 26816300.

- "Guide to breastfeeding" (PDF). www.womenshealth.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- "Breastfeeding checklist: How to get a good latch". WomensHealth.gov. 2017-06-09. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Common questions about breastfeeding and pain". womenshealth.gov. 2017-06-09. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "WHO - Breastfeeding: Only 1 in 5 countries fully implement WHO's infant formula Code". www.who.int. Archived from the original on August 6, 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Santos, Kamila Juliana da Silva; Santana, Géssica Silva; Vieira, Tatiana de Oliveira; Santos, Carlos Antônio de Souza Teles; Giugliani, Elsa Regina Justo; Vieira, Graciete Oliveira (2016). "Prevalence and factors associated with cracked nipples in the first month postpartum". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 16 (1): 209. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0999-4. ISSN 1471-2393. PMC 4975913. PMID 27496088.

- "Sore or cracked nipples when breastfeeding, Pregnancy and baby guide". www.nhs.uk. National Health Services (UK). 2017-12-21. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Walker 2011, p. 533.

- "Nipple discharge: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Nipple discharge". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- "How Is Breast Cancer in Men Diagnosed?". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Cuhaci, Neslihan; Polat, Sefika Burcak; Evranos, Berna; Ersoy, Reyhan; Cakir, Bekir (2014). "Gynecomastia: Clinical evaluation and management". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 18 (2): 150–158. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.129104. ISSN 2230-8210. PMC 3987263. PMID 24741509.

- Hansen 2010, p. 83.

- "Breast skin and nipple changes: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - M. Hussain, L. Rynn, C. Riordan and P. J. Regan, "Nipple-areola reconstruction: outcome assessment"; European Journal of Plastic Surgery, Vol. 26, Num. 7, December, 2003

- "CDC - Bring Your Brave Campaign - Symptoms of Breast Cancer". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Breast Cancer in Young Women". October 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Nepal art" (PDF). www.who.int. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-25. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- "Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Walker 2011, p. 524.

- Walker 2011, p. 530.

- Gerber B, Krause A, Reimer T, et al. (2003). "Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure". Ann. Surg. 238 (1): 120–7. doi:10.1097/01.SLA.0000077922.38307.cd. PMC 1422651. PMID 12832974.

- Mokbel R, Mokbel K (2006). "Is it safe to preserve the nipple areola complex during skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer?". Int J Fertil Female's Med. 51 (5): 230–2. PMID 17269590.

- Sacchini V, Pinotti JA, Barros AC, et al. (2006). "Nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer and risk reduction: oncologic or technical problem?". J. Am. Coll. Surg. 203 (5): 704–14. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.015. PMID 17084333.

- "Toplessness - the one Victorian taboo that won't go away". BBC News. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- "Why Are Women Expected to Keep Their Nipples Covered?". 14 February 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- D. Leder, The Body in Medical Thought and Practice, page 223, Springer Science & Business Media, 1992, ISBN 978-0-7923-1657-2

- "Erie v. Pap's A. M., 529 U.S. 277 (2000)". Justia Law. Justia. March 2000. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

Nudity cannot be considered an inherent form of expression.

- "Community Guidelines". help.instagram.com. Instagram. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Instagram Clarifies Its No-Nipple Policy". 17 April 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- Toor, Amar (6 December 2016). "Genderless Nipples exposes Instagram's double standard on nudity". The Verge. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- "Art student challenges 'sexist' ban on nipples on Instagram with new project - BBC Newsbeat". BBC News. 6 June 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Shire, Emily (9 September 2014). "Women, It's Time to Reclaim Our Breasts". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- "Community Standards". m.facebook.com. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- "Is Facebook going to start freeing the nipple?". Fox News. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Shire, Emily (9 September 2014). "Women, It's Time to Reclaim Our Breasts". The Daily Beast.

- Harvey, John H.; Wenzel, Amy; Sprecher, Susan (2004). The Handbook of Sexuality in Close Relationships. Psychology Press. p. 427. ISBN 978-1135624705. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Kinsey, Alfred C.; Pomeroy, Wardell B.; Martin, Clyde E.; Gebhard, Paul H. (1998). Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Indiana University Press. p. 587. ISBN 978-0253019240. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

There are some females who appear to find no erotic satisfaction in having their breasts manipulated; perhaps half of them derive some distinct satisfaction, but not more than a very small percentage ever respond intensely enough to reach orgasm as a result of such stimulation (Chapter 5). [...] Records of females reaching orgasm from breast stimulation alone are rare.

- Boston Women's Health Book Collective (1996). The New Our Bodies, Ourselves: A Book by and for Women. Simon & Schuster. p. 575. ISBN 978-0684823522. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

A few women can even experience orgasm from breast stimulation alone.

- Merril D. Smith (2014). Cultural Encyclopedia of the Breast. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 71. ISBN 978-0759123328. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Justin J. Lehmiller (2013). The Psychology of Human Sexuality. John Wiley & Sons. p. 120. ISBN 978-1118351321. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Komisaruk, B. R.; Wise, N.; Frangos, E.; Liu, W.-C.; Allen, K; Brody, S. (2011). "Women's Clitoris, Vagina, and Cervix Mapped on the Sensory Cortex: fMRI Evidence". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (10): 2822–30. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02388.x. PMC 3186818. PMID 21797981.

- Stephanie Pappas (August 5, 2011). "Surprise finding in response to nipple stimulation". CBS News.

- Disser, Nicole (19 August 2014). "This New Bushwick Bar Is The Most Literal Boobie Trap We've Ever Seen". Bedford and Bowery.

- Harper, Douglas (2001–2010). "nipple". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Harper, Douglas (2001–2010). "teat". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Harper, Douglas (2001–2010). "tit (1)". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

General bibliography

- Davidson, Michele (2014). Fast facts for the antepartum and postpartum nurse: a nursing orientation and care guide in a nutshell. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, LLC. ISBN 978-0-8261-6887-0.

- Durham, Roberta (2014). Maternal-newborn nursing: the critical components of nursing care. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0803637047.

- Hansen, John (2010). Netter's clinical anatomy. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 9781437702729.

- Henry, Norma (2016). RN maternal newborn nursing: review module. Stilwell, KS: Assessment Technologies Institute. ISBN 9781565335691.

- Lawrence, Ruth A.; Lawrence, Robert M. (13 October 2015). Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Professional. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 227–8. ISBN 978-0-323-39420-8.

- Walker, Marsha (2011). Breastfeeding management for the clinician: using the evidence. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 9780763766511.