Nizhnetoyemsky Selsoviet

Nizhnetoyemsky Selsoviet (Russian: Нижнетоемский сельсовет) is the low-level administrative division (a selsoviet) of Verkhnetoyemsky District of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia.[1] It was formed along with other fourteen selsoviets in April 1924 and occupied the territory of the former Nizhnetoyemskaya Volost of the former Solvychegodsky Uyezd of Northern Dvina Governorate.[2] The administrative center of the selsoviet is located in the village of Burtsevskaya, at the confluence of the Nizhnyaya Toyma and the Northern Dvina.[1]

The volost had been attested through archive records since the 16th century, but its name, known since the 12th century, refers to ancient speakers of Uralic languages that were by then already extinct or assimilated.

A station on the ancient trading route along the Northern Dvina River, in the end of the 17th century the volost became a hub of the Old Believers flight to the north.[3] The government suppressed the dissenters, the Russian Orthodox Church responded with continuous missionary activities, and in the 19th century the village was brought back into official Orthodoxy.[3]

The craftsmen of the volost developed a unique school of folk painting, notable for its use of black, red and gilding over a white background. This art, limited to household artifacts like distaff boards and murals over log houses and Russian stoves, remained unknown to historians and collectors until Olga Kruglova rediscovered it in 1959.[4]

Geography

A community in this area developed at the confluence of the Nizhnyaya Toyma and the Northern Dvina Rivers. The Nizhnyaya Toyma River freezes in November, thaws in late April or May, and allows commercial timber rafting.[5] Its valley, with an area of 1740 square kilometers, is continuously covered with small hills and ridges.[5] These terminal moraine ridges mark the southernmost extreme of the prehistoric glacier expansion.[6]

Yury Arbat, an ethnographer who studied the folk art of Arkhangelsk outback in the 1960s, described the place:

Nizhnyaya Toyma is not a village ... but a group of villages under a common title. An observer standing by the Nizhnyaya Toyma River, looking away from the Northern Dvina, sees a coastal village called Strelka (Spit) on a cape between two rivers. Further right is a boarding school and a diner, and the Krasnaya Gora (Red Hill) village behind them. Then there are Kholm (Hill) and Zagorye (Behind the Hill). Up on the crest are Navolotskaya and Vizhnitsa, the administrative center, behind it. The Gorodishche on the opposite side of Nizhnyaya Toyma River, is quite likely an ancient fort ... Eleven such villages, in total, compose Nizhnyaya Toyma.[7]

At least some of these villages, according to Arbat, sported traditional large, spacious Pomor type log houses with carved balconies and traditional exterior murals in local style.[8]

History

Etymology

The toponym Toyma is common to all northern Russian territories, from Toyma in Karelia to Toyma River in the Republic of Tatarstan. It relates to an extinct Finnic ethnonym also known to the Novgorodians since (at least) the beginning of the 12th century. Janet Martin considered Toima (sic) the southern extreme of Novgorodian control over the Dvina basin in this period.[9] The first mention of Toyma, paying tribute to Novgorodians, is dated 1137[10] but there is no evidence that the word Toyma relates to the present-day area or its neighbor, Verkhnetoyemsky Selsoviet. The 1219 chronicle mentions ethnonym toymokary (Russian: ... И поиде тои зимö Семьюнъ Öминъ въ 4 стöх на Тоимокары ...). The 1237 Tale of the Death of the Russian Land mentions "Toyma pagans" living between "the Karelians" and Veliky Ustyug (Russian: ...от корöлы до Оустьюга, гдö тамо бяхоу тоимици погании...),[11] a location roughly aligned with the Northern Dvina basin.

Russian linguists argue whether the ethnonym Toyma relates to a specific tribe, a tribal group, a language or a whole continuum of Finno-Ugric languages.[12] Evgeny Chelimsky applied ethnonym Toyma to the wide area in the southern part of Northern Dvina basin and wrote that it is equivalent to the Northern Finns in Aleksandr Matveyev's classification.[13] Matveyev objected, writing that the Northern Finnish continuum was considerably wider than Toyma's, and that the hypothetical Toyma people occupied only a minor portion of it.[14] He preferred to equate the Toyma with a particular tribe that lived in Nizhnaya Toyma area, and noted that it also could belong to Permic languages.[15] At any rate, the Toymas disappeared before the 17th century, when their existence could be recorded in Muscovite sources, either through russification or through earlier assimilation by other Finnic tribes.

Trade route

The west-east trade route along the Northern Dvina from Scandinavia and Novgorod to Bjarmaland has been known since the early Middle Ages but then the name of Toyma disappeared from Russian records until 1552, when Ivan IV of Moscow subordinated Toyma lands to the chief of Vaginsky Uyezd.[16]

The travel along the Northern Dvina has been extensively documented by the 1663 Dutch embassy to Muscovy headed by Koenraad van Klenk. The complete travel from the Netherlands to Moscow via Nordcap and Arkhangelsk took 175 days (return route: 125 days). The upstream travel from Arkhangelsk to Nizhnyaya Toyma took 14 days, from Nizhnyaya Toyma to Veliky Ustyug 11 days (downstream: 5 and 5 days).[17]

Raskol

According to the 1676–1681 population audit, Nizhnetoymenskaya Volost consisted of 34 villages with only 171 households (including 33 abandoned houses).[16] Local records attested significant decrease in population: some men were drafted into the troops, others left to seek fortune in Siberia, or simply disappeared.[16]

At the same time the Northern Dvina River became an escape route for the Old Believers, prosecuted by the government. The first record of the dissidents settling in Permogorye is dated 1686.[3] In March 1690, 212 dissidents from different volosts burned themselves in Cherevkovo in protest against a punitive expedition searching the area.[3] Self-immolations continued through the 18th century, police raids—until 1905. Cherevkovo, a village close to the Nizhnyaya Toyma, became a major Old Believers shrine and held its faith until the 1930s.[3] The Nizhnyaya Toyma River hosted settlements of the Aaronovtsy, a pro-marriage branch of the Filippovtsy sect established in the beginning of the 19th century.[3] Two other denominations active in the region were the Fedoseevtsy and the Danilovtsy.[18]

The official church considered Nizhnyaya Toyma and Cherevkovo areas especially dangerous (as opposed to the "safe" Verkhnyaya Uftyuga nearby) and maintained active missionaries in the area until the October Revolution; the volost even hosted missionary conventions.[19] The grand mainstream Church of Theotokos Orans, now dilapidated after decades of neglect, was erected in 1818. The volost, once completely "dissident", firmly returned into communion with the official church in the second half of the 19th century; isolated communities of Old Believers survived in nearby forests into the 20th century.[19]

Civil War

In 1919, the volost, as part of the whole upper Northern Dvina, became the site of a final battle between the British occupation forces and the Bolshevik troops.[20] In the beginning of the 1919 campaign the area was used by the air wing of the Red North Dvina flotilla.[21] Wheeled planes were stored in canvas tents on the coast, seaplanes on barges equipped with slipway ramps (leaky floats forced the Reds to pull their seaplanes out of water after each flight).[21] In May–June the Red airplanes relocated to Puchuga; on June 17 the British airplanes attacked the Puchuga airfield and destroyed 11 Red airplanes on the ground.[21]

Naval action also concentrated around Puchuga and gradually moved upstream.[21] The British employed river monitors (M27, M31, M33, Humber and Saikala), fast small boats and Fairey-IIIB seaplanes, one of which was shot down on July 14; local peasants caught the crew and gave them to the Reds.[20] The Bolsheviks operated makeshift gunboats carrying guns up to 130-mm caliber (the gunboats equipped in Petrograd with 203-mm guns were not yet ready for action).[20] They harassed their enemy with anchored and free-floating naval mines but the British easily recovered these mines and reused them against the Reds.[20]

On August 10, the British routed the Bolshevik ground forces near Borok (Boretskaya); the remaining Bolsheviks broke through the woods to the villages near the Nizhnyaya Toyma.[20] Their flotilla was temporarily split into two screening units guarding the villages of Puchuga and Sludka; ground forces marched forward to intercept the British.[20] On the night of August 13–14, the British secretly moved their ground artillery in the rear of the Bolshevik gunboats and shelled them down at close distance; Bolshevik infantry, again, retreated to the Nizhnyaya Toyma.[20] They were not aware that the British action was merely a diversion covering their general evacuation from Northern Russia.[20] The Bolshevik flotilla on the Northern Dvina existed until May 1920; minesweeping of the river was not completed until 1921.[20]

Painting school

Discovery

The volost was a center of traditional wood painting crafts discovered only in 1959 by ethnographers from the Zagorsk Museum.[4] The Zagorsk Expedition, led by Olga Kruglova, looked for the survivors of the Permogorye tradition of painting in black and red colours over a yellow background.[4] Their favorite motifs were the Sirin Bird and the black horses, symbols of a wealthy household.[4] Historians found plenty of these artifacts in and around Permogorye and Mokraya Yedoma (both names refer to clusters of villages rather than standalone communities), and as they traveled some 150 kilometers downstream the Northern Dvina River, to the Nizhnyaya Toyma, they discovered a yet unknown and completely different type of painting.[8]

Motifs and colours

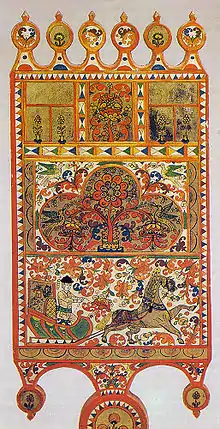

Toyma artists employed cinnabar painting over either white or gilded background, and their signature motif was a festive marriage ride hauled by two horses.[8] Two notable families of painters, the Tretyakovs and the Menshikovs, employed black, red, green, rarely blue and pink paint over a white background; one horse in their marriage rides was uniformly gilded, another was red or green with silver trim.[8] These families produced folk artists and Orthodox icon painters, and the folk line of their art reused the motifs and layout found in icons.[8] They

Leonid Latynin also noted the tree motif, common to all Northern Russian folk art.[22] Similar motifs were practiced in nearby Borok and Puchuga.[8] Victor Vasilenko classified Nizhaya Toyma painting under Shenkursk art heading (after the nearby town of Shenkursk) although, according to Yury Arbat, a Toyma-Borok art would be more descriptive.[8] The latter name, however, is ambiguous because the village of Toyma in Komi Republic had its own distinct painting tradition based on the Mezen school and unrelated to Nizhnaya Toyma.[23]

A typical spinning distaff from Toyma is divided vertically into three parts. The lower third features the trademark marriage ride, usually with only one human figure—the bridegroom. The middle third is filled with a complex floral ornament, sometimes with mythical birds. The upper and the most standardized part of the board is split horizontally into three "windows". Two side windows are adorned with images of pot flowers, in between them was a central tree of life motif.[8] Yury Arbat linked strict geometric division of the Toyma board to the Orthodox iconostasis design.[8]

Decline

By the 1960s, the craftsmen of the selsoviet still remembered their best painters of the 19th century (Ivan Tretyakov the elder, 1837–1922) and maintained their traditions.[8] The oldest painter witnessed by Arbat, a 95-year-old spinster from Borok, was still painting spinning distaffs, but most active craftsmen had already switched to interior murals over Russian stoves and into painting handmade wallpaper.[8] This placed them at disadvantage to artists from Khokhloma or Palekh who produced small, portable and marketable artifacts: the art of Toyma remained locked in peasant houses until they crumbled or burnt down, unknown even to collectors from Arkhangelsk.[8]

References

Notes

- Государственный комитет Российской Федерации по статистике. Комитет Российской Федерации по стандартизации, метрологии и сертификации. №ОК 019-95 1 января 1997 г. «Общероссийский классификатор объектов административно-территориального деления. Код 11 208 832», в ред. изменения №278/2015 от 1 января 2016 г.. (State Statistics Committee of the Russian Federation. Committee of the Russian Federation on Standardization, Metrology, and Certification. #OK 019-95 January 1, 1997 Russian Classification of Objects of Administrative Division (OKATO). Code 11 208 832, as amended by the Amendment #278/2015 of January 1, 2016. ).

- Архивный отдел администрации Архангельской области. Государственный архив Архангельской области. (1997). Административно-территориальное деление Архангельской губернии и области в XVIII-XX веках. Архангельск: Правда Севера. p. 135.

- Shchipin 2008, chapter 1

- Arbat 1968, chapter 1

- Nizhnyaya Toyma River entry in Russian in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- Demidov et al., p. 330

- Complete paragraph in Russian: "Нижняя Тойма — это тоже не село, а, как и Мокрая Едома и Дракованова Кулига, группа деревень, объединенных общим названием. Если стоять у речки Нижней Тоймы спиной к Северной Двине — справа прибрежный поселок Стрелка, прямо на мысу, образуемом двумя реками. Еще правее кирпичное здание школы-интерната и столовой сельпо, а за ним село Красная Гора. Поглубже Холм (Бурцевская), Загорье. На взгорье — Наволоцкая, а за ней центр сельского Совета — Вижница. Слева, на другом мысу Нижней Тоймы,— Городище. Видно, там в древние времена стояло укрепление, с двух сторон защищенное водой. Поглубже — Нижний Ручей, названный так по протоке Северной Двины, затем тесно слившиеся Абакумовская, Первая и Вторая Жерлыгинские. Одиннадцать этих деревень и составляют Нижнюю Тойму." – Arbat 1968, chapter 2.

- Arbat 1968, chapter 2

- Martin 2004, p. 57

- Martin 2004, p. 55, provides a list of tax-paying possessions of Novgorod in 1137, including Toyma.

- Original Russian version of the Tale of the Death of the Russian Land, second paragraph.

- Matveev 2007, provides a roundup of opposing views on the subject

- Chelimsky 2006, pp.38–39

- Matveyev 2007, p. 23

- Matveyev 2007, p. 24

- History of Verkhaya Toyma land (in Russian)

- Koenraad van Klenk (in Russian) (1900 edition). Voyagie van den Heere Koenraad van Klenk, ambassadeur aen zyne Zaarsche Majesteyt van Moscovien. Comments by the Russian editors, chapter VII.

- Shchipin 2008, chapter 2.

- Alekseyeva 2000

- Shirokorad 2006, part IV chapter 3

- Shirokorad 2006, part IV chapter 2

- Latynin 2006, chapter 1.

- Utkina 2003.

Sources

- O. V. Alekseyeva (2000). Mastera uftyugskoy rospisi (Мастера уфтюгской росписи). Proceedings of the III Ryabinin memorial conference (1999), Petrozavodsk.

- Yury Arbat (in Russian) (1968). Puteshestvie za krasotoy (Путешествие за красотой). Kultura, Moscow. Chapter 1, chapter 2.

- Evgeny Helimski (2006). Severno-zapadnaya gruppa finno-ugorskih yazykov (Северно-западная группа финно-угорских языков). Voprosy Onomastiki, No 3, 2006. pp. 38–51.

- Demidov, Houmark-Nielsen, Kjaer, Larsen, Lysa, Funder, Lunkka and Saarnisto (2004). Late Pleistocene stratigraphy and sedimentary environment of the Arkhangelsk area, northwest Russia, in: Quaternary glaciations: extent and chronology, Volume 1 (2004). Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-51462-7, ISBN 978-0-444-51462-2.

- Leonid Latynin (in Russian) (2006). "Osnovnye syuzhety russkogo narodnogo iskusstva" (Основные сюжеты русского народного искусства). Glas, Moscow. ISBN 5-7172-0078-1.

- Janet Martin (2004). Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54811-X, ISBN 978-0-521-54811-3.

- Aleksandr Matveyev (in Russian) (2007). K probleme klassifikatsii yazukov substratnoy toponimii russkogo severa (К вопросу классификации языков субстратной топонимии Русского Севера. Voprosy Onomastiki, No 4, 2007. pp. 14–27.

- V. I. Shchipin (in Russian) (2008). Staroobryadchestvo v verkhnem techenii Severnoy Dviny (Cтарообрядчество в верхнем течении Северной Двины). Chapter 1, chapter 2.

- Aleksandr Shirokorad (in Russian) (2006). Velikaya Rechnaya Voyna (Великая речная война). Veche, Moscow. ISBN 5-9533-1465-5.

- I. M. Utkina (in Russian) (2003). "Kollekzia pryalok iz sobraniya muzeya respubliki Komi" (Коллекция прялок из собрания музея республики Коми). Proceedings of the IV Ruabinin memorial conference (2003), Petrozavodsk.