Norwegian Coast Guard

The Norwegian Coast Guard (Norwegian: Kystvakten) is a maritime military force which is part of the Royal Norwegian Navy. The coast guard's responsibility are for fisheries inspection, customs enforcement, border control, law enforcement, shipping inspection, environmental protection, and search and rescue. It operates throughout Norway's 2,385,178-square-kilometer (920,922 sq mi) exclusive economic zone (EEZ), internal waters and territorial waters. It is headquartered at Sortland Naval Base. In 2013 the Coast Guard had 370 employees, including conscripts, and a budget of 1.0 billion Norwegian krone.

| Norwegian Coast Guard Kystvakten | |

|---|---|

Norwegian Coast Guards coat of arms | |

Racing stripe | |

Naval ensign | |

| Agency overview | |

| Employees | 829 employees (2013) |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Norway |

| Constituting instrument |

|

| Specialist jurisdiction |

|

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Sortland Naval Base |

| Parent agency | |

| Facilities | |

| Boats | |

| Planes | |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

.jpg.webp)

The force is subdivided into three main divisions. The Outer Coast Guard covers the EEZ and consists of three Nordkapp-class offshore patrol vessels, three Barentshav-class offshore patrol vessels as well as Ålesund, Svalbard and Harstad. The Inner Coast Guard consists of five Nornen-class patrol vessels. The Coast Guard has air support of the P-3 Orion patrol aircraft operated by the Royal Norwegian Air Force.

The Coast Guard has its basis in the defunct Fisheries Surveillance Service, which was established in 1908. It was a jointly military and civilian operation; it leased fishing vessels during the season to supplement larger navy vessels. This was converted into the Military Fisheries Surveillance in 1961. The Coast Guard was established on 1 April 1977, the same year as Norway delineated its EEZ. The restructuring led to the delivery of the Nordkapp-class and the Lynx helicopters. The Inner Coast Guard was established in 1996. The Coast Guard has participated in the 1990–91 Gulf War and the 2014 destruction of Syria's chemical weapons.

Jurisdiction and capabilities

The Coast Guard's main task is to assert and uphold Norwegian sovereignty over its inland waters, territorial waters and exclusive economic zone (EEZ).[2] Its structure is centered around a peace-time role,[3] with judicial basis in the Coast Guard Act (Kystvaktloven) of 1997.[4][1] It states that the authority of the Coast Guard lies with the primary agency responsible for a situation and that the Coast Guard's powers supplement these. However, the Coast Guard also holds a series of independent capabilities in which it can take action without external instruction. The act also grants the Coast Guard law enforcement jurisdiction in given circumstances.[5]

The Coast Guard is centered around providing services to a range of public agencies. These include the Coastal Administration, the Customs and Excise Authorities, the Directorate of Fisheries, the Environmental Agency, the Institute of Marine Research, the Mapping Authority, the Navy and the Police Service. This grants the Coast Guard a series of control rights including customs and border control for the Schengen Area.[5]

The most extensive work is carried out in relation to fisheries. This involves both inspection and assistance. Assistance duties to fishing vessels and other vessels at sea include firefighting, including the use of water cannons and smoke divers; removing foreign objects at sea; and mechanical help, diver assistance and towing for vessels which have experienced motor breakdown. Offshore vessels also feature equipment to contain oil spills.[6]

The Coast Guard is one of many agencies which can be called upon for search and rescue (SAR) missions. All such activity is either coordinated by the operations center of the respective police district, or by the Joint Rescue Coordination Centers in Southern Norway and Northern Norway, respectively.[7]

Structure

The Norwegian Coast Guard is a formation within the Royal Norwegian Navy. It is led by the Inspector of the Norwegian Coast Guard, who is subordinate to the Inspector General of the Royal Norwegian Navy.[8] The Coast Guard is one of two seaborne formations of the Navy, the other being the Norwegian Fleet. These share land-based support functions, such as naval bases and academies.[9]

The Coast Guard had its command and operative headquarters at Sortland Naval Base in downtown Sortland. It has a secondary base at Haakonsvern in Bergen, which is the primary base of the Navy. The Coast Guard uses four shared naval schools, the Norwegian Naval Academy in Bergen, RNoMS Tordenskjold at Haakonsvern, RNoMS Harald Hårfagre in Stavanger and the Navy Officer Candidate Schools in Bergen.[9]

Unlike the rest of the Navy, the Coast Guard has some of its ships owned and partially operated by private contractors. Four vessels, those in the Barentshav-class and the Reine-class, are owned by Remøy Management. The Fosnavåg-based company leases the ships for a reported 160 million Norwegian krone per year to the Coast Guard.[10] This includes all responsibility for maintenance and running of the galley and machine room.[11] Ålesund is owned by Fosnavåg Shipping,[12] while the Nornen-class is jointly owned by Remøy Management and Remøy Shipping.[13]

In 2012 the Coast Guard carried out about 1,700 inspections and issued warnings to about a quarter of these. It also participated in 171 search and rescue missions.[14] In 2013 it had a revenue of NOK 1,027 million. It had 829 employees that year, consisting of 382 military, 18 civilian employees and 429 conscripts. It performed 3,812 patrol-days and flew 599 helicopter-hours.[15] Coast Guard vessels have two crews, which alternate between being at sea and are on leave. This allows for high utilization of the fleet.[16]

Equipment

The fleet consists of fourteen vessels; nine are part of the Outer Coast Guard and five are part of the Inner Coast Guard.[17] The Coast Guard does not itself operate any aircraft; these are instead operated by the Royal Norwegian Air Force (RNoAF) or by private contractors.[18]

Outer Coast Guard vessels

The Coast Guard is replacing its existing Nordkapp-class vessels with significantly larger ice-capable ships, each displacing just under 10,000 tonnes. The three new Jan Mayen-class ships are armed with a 57mm main gun and capable of operating up to two medium-sized helicopters. The ships have an overall length of 446 feet with a beam of 72 feet and a draft of 20 feet. The maximum speed is 22 knots with more than 60 days endurance and the complement is up to 100 people.[19] The first ship, KV Jan Mayen, was launched by the Vard Tulcea shipyard in Romania in 2021 and towed to the Vard Langsten shipyard in Tomrefjord for completion. She was christened into service in November 2022,[20][21] having started builder's sea trials in October. The ship was delivered in early 2023.[22][23] The second ship of the class, KV Bjørnøya, was transferred to Norway for her final fit out at the Vard Langsten yard in February/March 2022[24][25][26] followed by the third and final ship, KV Hopen, in January 2023.[27]

NoCGV Svalbard (W303) has a displacement of 6,375 tonnes and an overall length of 103.7 meters (340 ft). It has a complement of 48, is armed with a Bofors 57 mm gun and can carry two helicopters. It predominantly serves Svalbard and the surrounding waters.[28]

The Coast Guard operated three Nordkapp-class offshore patrol vessels, Nordkapp (W320), Senja (W321) and Andenes (W322). They were predominantly used in the Barents Sea. They have a displacement of 3,200&tonnes and an overall length of 105 meters (344 ft). They operate at 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) and have a crew of 50. They are armed with a Bofors 57 mm gun and four 20 mm guns. They have space for one helicopter and are equipped with two torpedo tubes.[17] In 2022, it was indicated that Nordkapp would be transferred to the navy to operate in a mine countermeasures command role[29] while Senja was decommissioned in 2021.[30]

The Barentshav-class is made up of three vessels, Barentshav (W340), Bergen (W341) and Sortland (W342). Compared to older models they have been equipped with more extensive oil spill protection equipment. Supplemented with extensive firefighting and towing capabilities, they are built for expedient response for shipwrecking. They have a displacement of 4,000 tonnes, a length overall of 94 meters (308 ft) and a speed of 20 km/h (12 mph). Powered by liquefied natural gas, they have a crew of 40.[17]

NoCGV Harstad (W318) is primarily designed as a tow boat. It is well equipped to handle oil spills and is designed to handle both deep-submergence rescue vehicle and remotely controlled vehicles. It is equipped with a Bofors 40 mm gun. Harstad has a displacement of 3,130 tonnes, a length 83 meters (272 ft) and a crew of 22. It has an exceptional range and is used to refuel the outposts on Jan Mayen, Bjørnøya and Hopen.[31]

NoCGV Ålesund (W312) is a general-purpose offshore patrol vessel. It operates in Southern Norway and is mostly used for fisheries inspection in the Norwegian Sea. It has a displacement of 1,357 tonnes, is 63 meters (207 ft) long has a crew of 20 to 25. It is armed with a Bofors 40 mm gun.[12]

Inner Coast Guard vessels

The Inner Coast Guard operates five Nornen-class patrol vessels, Nornen (W33), Farm (W331), Heimdal (W332), Njord (W333) and Tor (W334). They have a displacement of 743 tonnes (731 long tons; 819 short tons) and a length overall of 47.2 meters (155 ft). They have a compartment of 20 crew and are armed with a 12.7 mm machine gun. Their 2,200-kilowatt (3,000 hp) diesel-electric engines provide a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).[13]

Aircraft

Prior to 2022, 333 Squadron operated six Lockheed P-3N Orion anti-submarine and maritime patrol aircraft. During peacetime their main role is intelligence and surveillance through a range of data sensing equipment.[32] The major advantage of the Orions was that they could cover a very large area; some missions allowed it to monitor 450,000 square kilometers (170,000 sq mi).[33] During wartime they would be used for anti-submarine warfare and intelligence. The Orions had a range of 8,000 kilometers (5,000 mi) and were based at Andøya Air Station.[32] From 2022, the squadron re-equipped with the Boeing P-8 Poseidon aircraft.

Lufttransport operates two Dornier 228 aircraft out of Svalbard Airport, Longyear. These fly a combined 400 hours per year for the Coast Guard for aerial surveillance of Svalbard.[34]

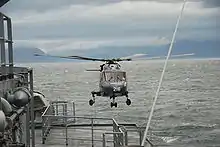

The 337 Squadron operated six Westland Lynx Mk 86 helicopters for the Coast Guard. These could be stationed on the Nordkapp-class, the Barentshav-class and on Svalbard. They were used to extend the mobility and efficiency of the vessel's operation. At any given time at least two Coast Guard vessels had a Lynx on board, which remained on two-week cycles. They were predominantly used to patrol the coast off Troms, Finnmark and the Barents Sea, including the seas off Svalbard. The Lynxes were plagued with technical problems causing them often to be out of service.[35] The helicopters had a range of 480 kilometers (300 mi), are 14.6 meters (48 ft) long and have a cruising speed of 222 km/h (138 mph).[36]

Norway was in the process of replacing the Lynx with the NHIndustries NH90. Fourteen units were ordered, of which eight were to be used with Coast Guard vessels. Six more were to be used by the Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates.[37] Operationally the helicopters were larger, with a length of 19.5 meters (64 ft), have a higher cruising speed of 259 km/h (161 mph) and have an improved range of 1,000 kilometers (620 mi).[38]

In June 2022 the Norwegian Minister of Defense announced the Norwegian Defence Material Agency was given the task to terminate the NH90 contract due to NHI not meeting contractual obligations, and announced that the NH90 is taken out of operation with immediate effect.[39]

In 2023, Norway announced the acquisition of 6 MH-60R helicopters. The helicopters were initially to be deployed with the Coast Guard, though they would be prepared to be equipped for anti-submarine operations.[40]

History

Predecessors

Following the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden in 1905 there arose a debate concerning access to fishing in Norwegian territorial waters. The predominant concern was that Swedes were fishing in Norwegian waters. Norway declared a 4-nautical-mile (7 km; 5 mi) territorial water in 1906 and instructed the navy to take action against any foreign vessels fishing in those waters.[41]

The following year British fishing vessels started fishing along the coast of Finnmark.[42] The fisheries inspection had an unarmed ship at the time, but asked for navy support. Eidsvold and Heimdal the following year was dispatched to aid.[43] The first arrest of a foreign vessel took place in 1911 of a British trawler outside Varangerfjorden.[44] The work was seasonal and was jointly financed by the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Fisheries. From 1914 it was entirely a military-funded operation. Later ships to participate were Farm and Valkyrje.[45]

.jpg.webp)

From 1924 Michael Sars also participated in this work.[46] The first dedicated coast guard vessel, Fridtjof Nansen, was commissioned in 1930.[47] From 1937 it was supported by two smaller vessels, Nordkapp and Senja. Meanwhile, an espionage program was established to better locate illegal fisheries.[48] All but Nordkapp were sunk in 1940 as part of the Second World War, although Senja was raised and repaired.[49]

After the end of the war, the fisheries surveillance services were reorganized. A number of whaling ships which had participated in the Arctic convoys were put into use as surveillance vessels while the navy focused on minesweeping.[50] The surveillance was supplemented with Flower-class corvettes. Three used River-class frigates were taken into use in 1956,[51] allowing Nordkapp to be decommissioned in 1956 and Senja two years later.[49] The corvettes and later the frigates were used both for fisheries inspection and held in readiness for war. They, therefore, incurred high operational costs, were inefficient and had a large degree of conscripts.[52]

The Ministry of Fisheries appointed a committee in 1958 to consider the organization, and it concluded that the inspections should be a military affair. This led to the establishment of the Military Fisheries Surveillance, which consisted of three squadrons. Two were subordinate to the Navy Commands in Northern and Western Norway, respectively, while the third, serving the Oslofjord, was subordinate to the Oslo office.[53] Meanwhile, work started on planning a new class of patrol vessels,[54] which resulted in the commissioning of the Farm-class patrol vessel in 1962 and 1963.[55] They were supplemented in 1964 by the used civilian Andenes-class patrol vessels.[56]

Establishment

Norway extended its fisheries zone to 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) from 1 September 1961, although it kept the old definition of territorial waters. This followed Norway's participation in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, where there was a growing consensus for such an approach.[57] Norway signed the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission in 1959, which took effect from 1970. This established common rules for fisheries within large parts of the European North Atlantic and standardized the inspection regimes.[58]

The surveillance ships carried out inspections during the fishing season and regularly caught foreign vessels using too small mesh size. However, few vessels were controlled due to the fleet's lack of suitability for the task. The issue was discussed in Parliament in 1973.[59] After negotiations with the neighboring countries, a series of trawler-free zones were established. Norway continued to work towards international agreements to secure an EEZ, led by Jens Evensen.[60]

Parallel with this work the government started considering a new organization for the fisheries surveillance. The Stoltenberg Commission, led by Thorvald Stoltenberg, was appointed in April 1974 and published its report in June 1975.[61] In Norway there has traditionally been a strong negative sentiment against allowing military forces to be used against civilians. The Military Fisheries Surveillance represented one of very few exceptions.[62] Several organizational models were discarded, including a civilian agency, a continuation of an integrated model and a virtual coast guard made up of units from various branches. Instead the commission proposed that the coast guard be organized as a separate unit under the navy. An important argument was to avoid duplicating services, such as an operative headquarter and naval bases. Meanwhile, the coast guard could act as a military presence to assert sovereignty.[61]

The Coast Guard was originally organized with two squadrons. The location of the garrison for Northern Norway became a heated political debate. A commission led by Johan Jørgen Holst recommended either Ramsund, Sortland or Harstad, and the former received the majority vote in Parliament. The government followed up on the commission's report and established the Norwegian Coast Guard on 1 April 1977. At this time the Coast Guard had ten vessels in Northern Norway in addition to a seasonal fleet of up to thirty smaller, civilian vessels. Four vessels, all rented, were used in Southern Norway.[18]

The government funded the establishment with 1.4 billion Norwegian krone (NOK), of which 1.2 billion was to be used for new ships. Two new P-3B Orions were bought for the 333 Squadron and the Coast Guard paid an hourly lease for their use in maritime surveillance. The new agency received three new helicopter-capable offshore patrol vessels, the Nordkapp-class. These were delivered in 1981 and 1982.[18] During the second half of the 1970s there was a discussion as to which helicopter should be procured. A government commission recommended the Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk, but the Westland Lynx was eventually preferred due to faster delivery and lower price.[63] To operate the six Lynxes, the 337 Squadron was established and became operational in 1983.[35] The Andenes-class was retired, while the Farm-class vessels were rebuilt and remained in service.[64]

Early operations

During the 1980s the Coast Guard's concentrated its work on fisheries surveillance. A major part of this involved inspection of the fisheries protection zones around Jan Mayen and Svalbard. Here Soviet and later Spanish fishing vessels were a major participant. The Coast Guard played a major role in assessing the amount of caught fish. In most cases where it found non-conformities the agency would issue warnings. In 1988 it carried out 1,273 inspections, of which 21 involved seizure and 16 were reported. However, written warnings were issued in 268 cases, and 106 oral warnings were given.[65]

Andenes carried out two research expeditions to the Antarctic, in 1984–85 and 1989–90 as part of the Pro Mare research program. It was also used to signal the territorial claim to Dronning Maud Land and the Weddell Sea.[66] Andenes also participated in the Gulf War as Norway's participation. It acted as a support ship of the Royal Danish Navy's Olfert Fischer frigate.[67]

Decreased fish stock during the 1990s resulted in more strict handling of violations. At the same time cooperation with neighboring countries improved. Greenlandic fishermen started fishing in the fisheries protection zones in 1991. In exchange for a Greenlandic acceptance of Norwegian and Russian management of the Barents Sea stocks, Greenland was issued quotas. This simply escalated the conflict, with Iceland joining fisheries from 1993. They claimed the protection zone was not valid in accordance with the Svalbard Treaty.[68] The issue peaked on 5 August 1994, when Senja seized an Icelandic trawler.[69] In 1997 the Coast Guard carried out 2,192 inspections, issued 566 warnings and seized 18 vessels.[70]

After whaling commenced in 1993, the Coast Guard was involved with in a series of skirmishes with vessels from Greenpeace and Sea Shepherd. The conflict with the latter peaked in 1994 with a collision between Andenes and Whales Forever. After this incident, the forceful threat from anti-whaling activists diminished.[68]

Change of scope

Following the end of the Cold War there arose a debate regarding the Coast Guards scope. With a diminishing threat from Russia, the navy decided that it would downplay the military role of the Coast Guard. This would allow the Norwegian Fleet and the Coastal Artillery to focus on training while the Coast Guard would focus entirely on its core tasks.[71] In line with the trend of new public management, the government was eager to introduce user payment for the Coast Guard. This would have involved the various civilian agencies, such as the JCRRs, having to pay for Coast Guard services. The Navy argued that a key role of the Coast Guard was a constant presence and that invoicing for use would decrease its efficiency since it had low marginal costs with participating in SAR missions. In the end user payment was abandoned.[72]

By the late 1980s the L-3B Orions were becoming obsolete. Five were therefore sold to the Spanish Air Force. Two were upgraded to the L-3N standard and four more new N-variants were bought.[32]

Most Coast Guard ships have been leased instead of owned. This was a continuation of the practice of the Military Fisheries Surveillance. At first, these were issued on short-term contracts, but from 1994 ten-year contracts were used instead. As part of this arrangement two new major ships were built, Ålesund and Tromsø. They were built based on specifications from the Coast Guard and included equipment for handling oil spills.[72]

The Coast Guard underwent a major restructuring in the mid-1990s. The former services became the Outer Coast Guard (Ytre Kysvakt, YKV) while a new Inner Coast Guard (Indre Kystvakt, IKV) was established to patrol the territorial waters. The latter was based on seven patrol areas, each assigned one vessel. A new Coast Guard Act was passed in 1997 and took effect in 1999. This involved a clearer division of roles between the Norwegian Fleet and Coastal Artillery on the one hand, and the Coast Guard on the other. The goal was to allow for closer integration of the Coast Guard and other civilian search and rescue agencies.[4]

The relationship with Russia was complicated. In 1993 the Norwegian and Russian Coast Guard held a common conference in Sortland and since communication has eased and several top-level conferences have been held.[73] Management in the Barents Sea is subordinate to the Joint Norwegian–Russian Fisheries Commission. Issues escalated in the early 2000s. In 2002 Russian inspectors boarded a Russian ship while it was being inspected by Norwegians. Three years later Elektron ran off with Norwegian inspectors on board.[74]

Svalbard was commissioned in 2002 as the first icebreaking vessel of the Coast Guard.[71] For the Inner Coast Guard, five Nornen-class patrol vessels were commissioned in 2007 and 2008.[75] Harstad was commissioned in 2009 and was followed up with the tree vessels in the Barentshav-class for the Outer Coast Guard.[75] Norway ordered fourteen NH90s in 2001. Eight of these were designated to the Coast Guard, while six will be used on the Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates. However, the first helicopter was not delivered until November 2011 and as of 2014 no Coast Guard variants have been completed.[76]

The Coast Guard was reorganized from 2012. After a controversy regarding the new location, the two squadrons were disbanded. The new structure has its head office at Sortland Naval Base. This allows all staff, previously with a command at Akershus Fortress in Oslo and the squadrons at Sortland and Haakonsvern to be co-located. All ships were subsequently re-registered with Sortland as their home port, although those based in Southern Norway retain use of Haakonsvern as their base.[14][77]

The Naval Home Guard commissioned two Reine-class patrol vessels in 2010.[78] One of these were transferred to the Coast Guard in 2013.[14] Andenes was dispatched to the Mediterranean Sea in May 2014 to participate in the destruction of Syria's chemical weapons. Replacing the frigate Helge Ingstad, Andenes was used to escort the freighter MV Taiko.[79]

Due to delays on the new replenishment oiler HNoMS Maud it was decided that both Reine-class patrol vessels would be transferred to the navy as auxiliary ships.[80]

References

- "Lov om Kystvakten (kystvaktloven)". Lovdata. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 462.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 473.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 463.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 464.

- Jensen 1998, p. 105.

- Ministry of Justice and the Police: 13

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 466.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 523.

- Eidsvik, Øyvind Lefdal (16 October 2014). "Krever mer i leie for kystvaktskip" (in Norwegian). Sysla. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "KV Barentshav" (in Norwegian). Remøy Management. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Jensen 1998, p. 136.

- "Polish-built ships" (PDF). Mashe Morze. September 2006. pp. 38–39. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "Kystvakten inn i 2013 med flere skip ute av drift". Nationen (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- "Forsvarets årsrapport 2013" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Armed Forces. 2014. pp. 49–51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- Jensen 1998, p. 107.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 487.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 467.

- "Norway's New Coast Guard Vessel Arrives for Fitting Out at Vard".

- https://www.nrk.no/mr/kystvakten-sitt-nye-skip-_jan-mayen_-er-ferdig_-_-viktig-for-beredskapen_-sier-justisministeren-1.16182764

- "Romanian Built Norwegian Coast Guard Ship Arrives – SeaWaves Magazine".

- "Norway's Newest Coast Guard Vessel Ready for Operations in the High North". High North News. 23 June 2023.

- https://www.janes.com/defence-news/naval-weapons/latest/first-jan-mayen-class-opv-for-norwegian-coast-guard-nears-completion

- "VARD transfers Norwegian Coast Guard's newest vessel to Norway". 12 March 2022.

- "Here comes Norway's new ice-strengthened coast guard ship". The Independent Barents Observer.

- Choi, Timothy (2019-06-13). "Recent Developments in Arctic Maritime Constabulary Forces: Canadian and Norwegian Perspectives". Arctic Relations. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- Nilsen, Thomas (2023-01-28). "Third new Norwegian Coast Guard vessel arrives". The Barents Observer. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "KV Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- https://www.forsvaret.no/aktuelt-og-presse/aktuelt/fra-kystvakt-til-marinefartoy-na-er-knm-nordkapp-klar-for-nato-oppdrag?q=knm%20nordkapp

- https://www.forsvaret.no/aktuelt-og-presse/aktuelt/slutten-pa-eit-kapittel-og-starten-pa-eit-nytt

- "KV Harstad" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

- Mo & Sælensminde 2013, p. 259.

- Jensen 1998, p. 111.

- "Kystvakt" (in Norwegian). Lufttransport. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Mo & Sælensminde 2013, p. 273.

- Mo & Sælensminde 2013, p. 272.

- Mo & Sælensminde 2013, p. 275.

- Mo & Sælensminde 2013, p. 274.

- "Norway terminates its contract for the NH90". regjeringen.no (Norwegian Government). 10 June 2022.

- Felstead, Peter (15 March 2023). "Norway to Replace its Cancelled NH90s with Six Sikorsky MH-60Rs". European Security and Defence. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- Jensen 1998, p. 29.

- Jensen 1998, p. 30.

- Jensen 1998, p. 31.

- Jensen 1998, p. 62.

- Jensen 1998, p. 34.

- Jensen 1998, p. 39.

- Jensen 1998, p. 44.

- Jensen 1998, p. 51.

- Jensen 1998, p. 54.

- Jensen 1998, p. 60.

- Jensen 1998, p. 61.

- Jensen 1998, p. 68.

- Jensen 1998, p. j68.

- Jensen 1998, p. 69.

- Jensen 1998, p. 71.

- Jensen 1998, p. 74.

- Jensen 1998, p. 87.

- Jensen 1998, p. 88.

- Jensen 1998, p. 89.

- Jensen 1998, p. 91.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 461.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 460.

- Jensen 1998, p. 114.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 469.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 477.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 484.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 486.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 479.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 480.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 481.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 470.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 471.

- Jensen 1998, p. 128.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 483.

- Terjesen, Kristiansen & Gjelsten 2010, p. 472.

- "Norway Growing Impatient With NH90 Delays". DefenseNews. 28 June 2012. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Berg-Hansen, Morten (15 September 2010). "Lager helt ny kystvakt". Bladet Vesterålen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "Olav Tryggvason". Maritimt Magasin (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Alfheim, Ruben Lund (20 August 2014). "Fikk medaljer for Syria-oppdrag" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ""Magnus Lagabøte"".

Bibliography

- Jensen, Jan P. (1998). Havets voktere – historien om Kystvakten (in Norwegian). Oslo: Schibsted. ISBN 82-516-1679-4.

- Ministry of Justice and the Police. The Norwegian Search and Rescue Service. p. 13. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Mo, Sverre; Sælensminde, Ole Bjørn (2013). Norske militærfly (in Norwegian). Bergen: Bodoni Forlag. ISBN 978-82-7128-687-3.

- Terjesen, Bjørn; Kristiansen, Tom; Gjelsten, Rune (2010). Sjøforsvaret i krig og fred (in Norwegian). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. ISBN 978-82-450-1014-5.

External links

- Official website (in Nynorsk)

- The Barentshav Class (Official website) (in Norwegian)

- The Reine Class (Official website) (in Nynorsk)

- NoCGV Harstad (Official website) (in Nynorsk)