Troms

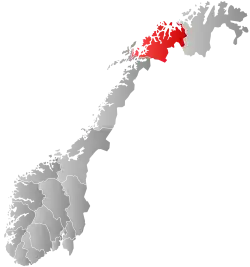

Troms (Norwegian: [trʊms] ⓘ; Northern Sami: Romsa;[3] Kven: Tromssa; Finnish: Tromssa) is a former county in northern Norway. On 1 January 2020 it was merged with the neighboring Finnmark county to create the new Troms og Finnmark county. This merger is expected to be reversed by the government resulting from the 2021 Norwegian parliamentary election.[4]

Troms fylke

Romssa fylka | |

|---|---|

Arnøyhøgda, Laukslettinden, Tjuvtinden and Rødhetta as seen over Skattørsundet in March 2012 | |

Flag  Troms within Norway | |

Troms fylke Troms within Troms  Troms fylke Troms fylke (Norway) | |

| Coordinates: 69.8178°N 18.7819°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Troms |

| District | Northern Norway |

| Established | 1866 |

| • Preceded by | Finnmarkens amt |

| Disestablished | 1 Jan 2020 |

| • Succeeded by | Troms og Finnmark |

| Re-established | 1 Jan 2024 (planned) |

| • Preceded by | Troms og Finnmark |

| Administrative centre | Tromsø |

| Government | |

| • Body | Troms County Municipality |

| • Governor (2017-2019) | Elisabeth Aspaker (H) |

| • County mayor (2011-2019) | Knut Werner Hansen (Ap) |

| Area (upon dissolution) | |

| • Total | 25,877 km2 (9,991 sq mi) |

| • Land | 24,884 km2 (9,608 sq mi) |

| • Water | 993 km2 (383 sq mi) 3.8% |

| • Rank | #4 in Norway |

| Population (30 September 2019) | |

| • Total | 166,375 |

| • Rank | #15 in Norway |

| • Density | 6/km2 (20/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | |

| Demonym | Tromsværing[1] |

| Official language | |

| • Norwegian form | Neutral |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-19 |

| Income (per capita) | 133,300 kr (2001) |

| GDP (per capita) | 211,955 kr (2001) |

| GDP national rank | #15 in Norway (2.11% of country) |

| Website | Official website |

It bordered Finnmark county to the northeast and Nordland county in the southwest. Norrbotten Län in Sweden is located to the south and further southeast is a shorter border with Lapland Province in Finland. To the west is the Norwegian Sea (Atlantic Ocean).

The entire county, which was established in 1866, was located north of the Arctic Circle. The Troms County Municipality was the governing body for the county, elected by the people of Troms, while the Troms county governor was a representative of the King and Government of Norway. The county had a population of 161,771 in 2014.

General information

Name

Until 1919, the county was formerly known as Tromsø amt. On 1 July 2006, the Northern Sami name for the county, Romsa, was granted official status along with Troms.[5]

The county (and the city of Tromsø) was named after the island Tromsøya on which it was located (Old Norse Trums). Several theories exist as to the etymology of Troms. One theory holds "Troms-" to derive from the old (uncompounded) name of the island (Old Norse: Trums). Several islands and rivers in Norway have the name Tromsa, and the names of these are probably derived from the word straumr which means "(strong) stream". (The original form must then have been Strums, for the missing s see Indo-European s-mobile.) Another theory holds that Tromsøya was originally called Lille Tromsøya (Little Tromsøya), because of its proximity to the much bigger island today called Kvaløya, that according to this theory was earlier called "Store Tromsøya" due to a characteristic mountain known as Tromma (the Drum). The mountain's name in Sámi, Rumbbučohkka, is identical in meaning, and it is said to have been a sacred mountain for the Sámi in pre-Christian times.

The Sámi name of the island, Romsa, is assumed to be a loan from Norse – but according to the phonetical rules of the Sami language the frontal t has disappeared from the name. However, an alternative form – Tromsa – is in informal use. There is a theory that holds the Norwegian name of Tromsø derives from the Sámi name, though this theory lacks an explanation for the meaning of Romsa. A common misunderstanding is that Tromsø's Sámi name is Romssa with a double "s". This, however, is the accusative and genitive form of the noun used when, for example, writing "Tromsø Municipality" (Romssa Suohkan).

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of Troms was made by Hallvard Trætteberg (1898–1987) and adopted by royal resolution on 15 January 1960. The official blazon in Norwegian ("På rød bunn en gull griff") translates to "On a field Gules a griffin [segreant] Or."[6] Trætteberg chose to have the griffin as charge because that animal was the symbol of the mighty clan of Bjarne Erlingsson on Bjarkøy in the 13th century.[7]

Geography

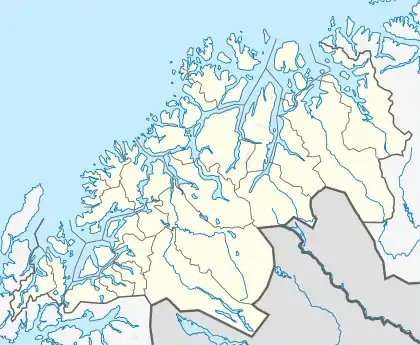

Troms, when it existed, was located in the northern part of the Scandinavian peninsula. Due to the long distance to the more densely populated areas of the continent, this is one of the least polluted areas of Europe. Troms has a very rugged and indented coastline facing the Norwegian Sea. However, the large and mountainous islands along the coast provide an excellent sheltered waterway on the inside. Starting in the south, the largest islands are: northeastern part of Hinnøya (the southern part is in Nordland), Grytøya, Senja, Kvaløya, Ringvassøya, Reinøy, Vanna, and Arnøy. Some of these islands, most noteworthy Senja, have a rugged outer coast with steep mountains, and a more calm eastern shore. There are several large fjords that stretch quite far inland. Starting in the south, the largest fjords are Vågsfjorden, Andfjorden (shared with Nordland), Malangen, Balsfjord, Ullsfjord, Lyngen, and Kvænangen (fjord). The largest lake is Altevatnet in the interior of the county.

There are mountains in all parts of Troms; the most alpine and striking are probably the Lyngen Alps (Lyngsalpene), with several small glaciers and the highest mountain in the county, Jiekkevarre with a height of 1,833 m (6,014 ft). Several glaciers are located in Kvænangen, including parts of the Øksfjordjøkelen, the last glacier in mainland Norway to drop icebergs directly into the sea (in the Jøkelfjord). The largest river in Troms (waterflow) is Målselva (in Målselv), and the largest (not the highest) waterfall is Målselvfossen at 600 m (2,000 ft) long and 20 m (66 ft) high. Marble is present in parts of Troms, and thus numerous caves, as in Salangen and Skånland.

Climate

Located at a latitude of nearly 70°N, Troms has short, cool summers, but fairly mild winters along the coast due to the temperate sea; Torsvåg Lighthouse in Karlsøy has January 24-hr average of −1 °C (30 °F). Tromsø averages −4 °C (25 °F) in January with a daily high of −2 °C (28 °F), while July averages 12 °C (54 °F) with high of 15 °C (59 °F). Temperatures are typically below freezing for about 5 months (8 months in the mountains), from early November to the beginning of April, but coastal areas are moderated by the sea: with more than 130 years of official weather recordings, the coldest winter temperature ever recorded in Tromsø is −20.1 °C (−4.2 °F) in February 1985.[8] The all-time high for Troms is 33.5 °C (92.3 °F) recorded in Bardufoss July 18, 2018. Thaws can occur even in mid-winter. There was often snow in abundance, and avalanches were not uncommon in winter. With the prevailing westerlies, lowland areas east of mountain ranges have less precipitation than areas west of the mountains.

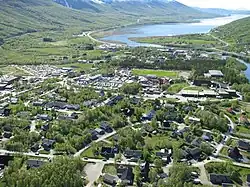

Skibotn (elevation: 46 m or 151 ft) in Storfjord is the location in Norway which has recorded the most days per year with clear skies (no clouds). Winter temperatures in Målselv and Bardu can get down to −35 °C (−31 °F), while summer days can reach 30 °C (86 °F) in inland valleys and the innermost fjord areas, but 15 to 22 °C (59 to 72 °F) is much more common. Along the outer seaboard, a summer day at 15 °C (59 °F) is considered fairly warm.

| Climate data for Tromsø, Troms county, Norway 1961-1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.1) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

0.1 (32.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 95 (3.7) |

87 (3.4) |

72 (2.8) |

64 (2.5) |

48 (1.9) |

59 (2.3) |

77 (3.0) |

82 (3.2) |

102 (4.0) |

131 (5.2) |

108 (4.3) |

106 (4.2) |

1,031 (40.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 13.7 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 13.4 | 13.1 | 15.5 | 17.1 | 14.8 | 15.1 | 159.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 3 | 32 | 112 | 160 | 218 | 221 | 205 | 167 | 92 | 49 | 6 | 0 | 1,265 |

| Source: Norwegian Meteorological Institute[9] | |||||||||||||

Sunlight

The aurora borealis is a common sight in the whole of the former Troms, but not in summer as there is no darkness. As with all areas in the polar latitudes, there are extreme variations in daylight between the seasons. As a consequence of this, the length of daylight increases (late winter and spring) or decreases (autumn) by 10 minutes from one day to the next.[10]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11:31 – 12:17 | 08:16 – 15:43 | 06:07 – 17:41 | 04:43 – 20:48 | 01:43 – 23:48 | Midnight sun | Midnight sun | 03:44 – 21:50 | 05:56 – 19:20 | 07:54 – 17:04 | 09:25 – 13:32 | Polar night |

| Source: Almanakk for Norge; University of Oslo, 2010. Note: The sun is below the horizon until 15 January in Tromsø, but the low sun is blocked by mountains and not visible until 21 January. | |||||||||||

Nature

Moose, red fox, hare, stoat, and small rodents are common in all of Troms county. Brown bears are sighted in the interior parts of the county in the summer. Other animals that can be seen are reindeer (interior mountain areas, with Sami owners), wolverine (interior mountain areas), Eurasian otters (along the coast and rivers), Eurasian lynx (in the forests), and harbour porpoises in the fjords. Sperm whales, killer whales and humpback whales are often seen in Andfjorden. Some of the common birds are ptarmigan, sea eagles, European herring gulls, and great cormorants.

The sheltered valleys in the interior of Troms have the highest tree line (summer warmth and length is the limiting factor), with downy birch reaching an elevation of 700 m (2,300 ft) on the southern slope of Njunis; all over Troms county birch trees forms the tree lines, often 200 metres (660 ft) above other trees. Rowan, aspen, willow, grey alder, and bird cherry are common in the lower elevations.

.jpg.webp)

Scots pine reaches an elevation of almost 400 m (1,300 ft) in Dividalen, where some of the largest trees are 500 years old. The upper part of the valley is protected by Øvre Dividal National Park,[11] which was enlarged in 2006.[12] In 2011, the Rohkunborri National Park (571 square kilometres or 220 square miles) was established in Bardu municipality, bordering Sweden and only a few kilometers south of Øvre Dividal National Park.[13]

The inland valleys, like Østerdalen (with Altevatnet), Kirkesdalen, Dividalen, Rostadalen, Signaldalen, and Skibotndalen, are perfect for summer hiking, with their varied nature, mostly dry climate and not too difficult terrain, although there are many accessible mountains for energetic hikers.

Reisadalen is one of the most idyllic river valleys in Norway; from Storslett in Nordreisa the valley stretches south-southeast, covered with birch, pine, grey alder, and willow. The northern part of the valley is 5 km (3.1 mi) wide, with 1,200-metre (3,900 ft) high mountains on both sides; the southern part of the valley narrows to a few hundred metres (canyon), with increasingly dry climate. The valley floor is fairly flat with little height difference for 70 km (43 mi) (to Bilto); the Reisa river can be navigated by canoe or river boat for much of this distance. The salmon swim 90 km (56 mi) up the river, and some 137 different species of birds have been observed. Several rivers cascade down into the valley; the Mollisfossen waterfall is 269 m (883 ft).[14] The valley ends 120 km (75 mi) southeast of Storslett, as the vast and more barren Finnmarksvidda plateau takes over. Reisa National Park protects the upper part of the valley.[15]

Economy

The city of Tromsø, in the north central part, was the county seat and an Arctic seaport, and seat of the world's northernmost university, renowned for research about the aurora borealis. The University of Tromsø has an astrophysical observatory located in Skibotn.[16] Tromsø was the only municipality in the former county with a strong population growth; most of the smaller municipalities experience decreasing populations as the young and educated moved to the cities, often in the southern part of Norway. Harstad is a commercial centre for the southern part of the former county, and has been chosen by Statoil as its main office in Northern Norway.

Along the coast and on the islands, fishing is dominant. Important ports for the fishing fleet are Skjervøy, Tromsø and Harstad. There is also some agriculture, especially in the southern part of the former county, which has a longer growing season (150 days in Harstad). Balsfjord is often regarded to be the most northern municipality with substantial agricultural activity in Norway, although there is also agriculture further north.

The Norwegian armed forces were vital employers in the former Troms, having the seat of the 6th army division, Bardufoss Air Station, helicopter wings and radar stations in the county. There are hospitals in Tromsø (university hospital and main hospital for North Norway) and Harstad.

While the busiest airport in the former Troms is Tromsø Airport, the southern part included Harstad/Narvik Airport, Evenes and Bardufoss Airport, with Sørkjosen Airport in the northeast. The E6 cuts through the county from Nordland into Gratangen in the south to Kvænangen in the north and then into Finnmark. The E8 road runs from Tromsø to Finland via Nordkjosbotn and the Skibotn valley. There are several large bridges; some of the largest are Tjeldsund Bridge, Mjøsund Bridge, Gisund Bridge, Tromsø Bridge and Sandnessund Bridge. There are several undersea road tunnels; Rolla to Andørja (in Ibestad), Tromsøya to the mainland (Tromsø), Kvaløya to Ringvassøya and Skjervøy to the mainland. The roads are well maintained, but have to go long detours around fjords. For this reason passenger boats are fairly popular, for example between Tromsø and Harstad, and there are also commercial flights inside the former county of Troms.

There was no railway in Troms, but in 2013, the government of Finland expressed interest in building a railway from the Finnish rail network to port facilities at Skibotn, though they also stated that they could not finance much of the cost.[17]

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 117,564 | — |

| 1961 | 127,771 | +8.7% |

| 1971 | 136,805 | +7.1% |

| 1981 | 146,818 | +7.3% |

| 1991 | 146,816 | −0.0% |

| 2001 | 151,777 | +3.4% |

| 2011 | 157,554 | +3.8% |

| 2021? | 168,953 | +7.2% |

| 2031? | 176,342 | +4.4% |

| Source: Statistics Norway.[18] | ||

Troms has been settled since the early Stone Age, and there are prehistoric rock carvings at several locations (for instance Ibestad and Balsfjord). These people made their living from hunting, fishing and gathering.

The first of the current ethnic groups to settle in the county were the Sami people, who inhabited Sápmi, an area much larger than today's Nordland, Troms and Finnmark counties. Archeological evidence has shown that a Norse iron-based culture in the late Roman Iron Age (200–400 AD), reaches as far north as Karlsøy (near today's Tromsø), but not further northeast.

The Norse with their iron and agriculture settled along the coast and in some of the larger fjords, while the Sami lived in the same fjord areas, usually just into the fjord and in the interior.[19] From the 10th century, Norse settlements start to appear along the coast further north, reaching into what is today the county of Finnmark.

Southern and mid-Troms was a petty kingdom in the Viking Age, and considered part of Hålogaland. Ottar from Hålogaland met King Alfred the Great around 890. The Viking leader Tore Hund had his seat at Bjarkøy. According to the sagas, Tore Hund speared King Olav Haraldsson at the Battle of Stiklestad. He also traded and fought in Bjarmaland, today the area of Arkhangelsk in northern Russia.[20] Trondenes (today's Harstad) was also a central Viking power centre, and seems to have been a gathering place.

Demographics

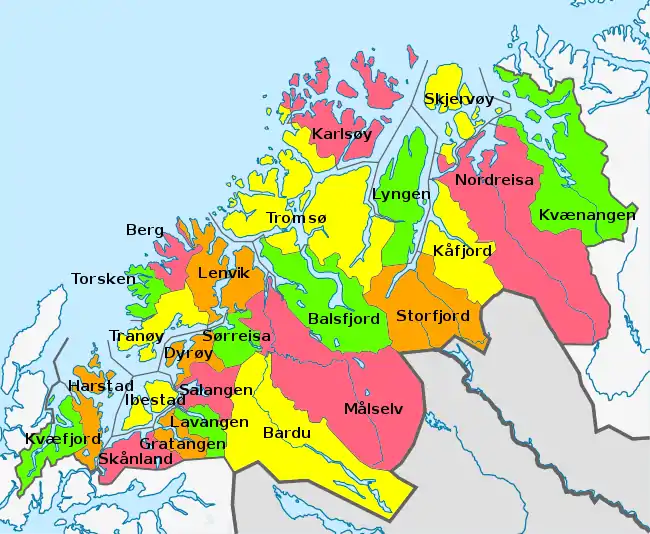

The Kven residents of Troms are largely descendants of Finnish immigrants who arrived in the area before the 19th century from Finland because of war and famine. They settled mainly in the northeastern part of Troms, in the municipalities of Kvænangen, Nordreisa, Skjervøy, Gáivuotna - Kåfjord and Storfjord, and some also reached Balsfjord and Lyngen.

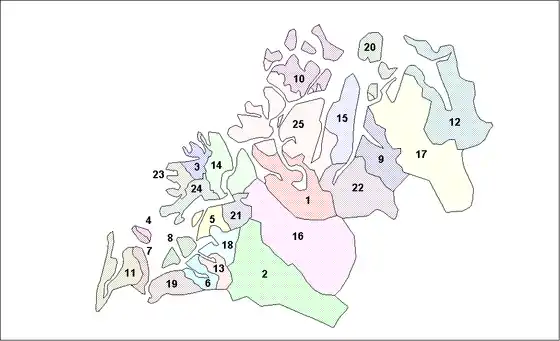

Municipalities

Troms county had a total of 24 municipalities at dissolution.

| Municipalities of Troms at time of 2020 dissolution | ||

|---|---|---|

| Key |  | |

Photo gallery

Inside Trondenes Church, the only medieval church in Troms

Inside Trondenes Church, the only medieval church in Troms Ersfjorden, Senja island

Ersfjorden, Senja island Skjervøy Church in northern Troms at night, February 2004

Skjervøy Church in northern Troms at night, February 2004 Sørvik in Harstad is at the southern tip of Troms

Sørvik in Harstad is at the southern tip of Troms Reindeer in Norway (Rekvika, Troms, Norway)

Reindeer in Norway (Rekvika, Troms, Norway) Summer evening in Jøkelfjord, Kvænangen.

Summer evening in Jøkelfjord, Kvænangen.

Notable people

- Samuel Georg Simeon Wennberg, member of parliament

See also

References

- "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- "Stadnamn og rettskriving" (in Norwegian). Kartverket. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- "Jubel i nord etter skilsmissen: – Nå skal vi feire!" (in Norwegian). NRK. 13 October 2021. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- "Offisielt samisk namn for Troms" (in Norwegian). Statens navnekonsulenter. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2006.

- "Troms" (in Norwegian). Arkivverket.no. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- "Hallvard Trætteberg: fylkesvåpen" (in Norwegian). Arkivverket.no. Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- "Yr coldest recordings in February". Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "eKlima Web Portal". Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 2004-06-14.

- "Sunrise and daylight in Tromsø". Gaisma.

- "I jervens rike". dirnat.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- "Øvre Dividal nasjonalpark utvidet". dirnat.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- "Rohkunborri nasjonalpark er opprettet" (PDF). Direktoratet for Naturforvalting (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- "Mollisfossen". mollis.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- "Mektig vassdragsnatur". dirnat.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- "Skibotn Astrophysical Observatory". Astrophysics Group of University of Tromso. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Nilsen, Thomas (December 3, 2013). "Katainen: Railway to Arctic Ocean is a great opportunity". Barents Observer.

- Projected population – Statistics Norway Archived 2013-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Urbańczyk, Przemyslaw (1992). Medieval Arctic Norway. Warsaw, Poland: Institute of the History of Material Culture, Polish Academy of Sciences. pp. 56–67. ISBN 978-83-900213-0-0.

- Bandlien, Bjørn. "Bjarmeland". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Statistics Norway – Church of Norway. Archived 2012-07-16 at archive.today

- "Statistics Norway – Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance. County. 2006–2010". Archived from the original on 2011-11-02. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

Other sources

- Haugan, Trygve B, ed. (1940). Det Nordlige Norge Fra Trondheim Til Midnattssolens Land. Trondheim: Reisetrafikkforeningen for Trondheim og Trøndelag.

- Moen, Asbjørn (1998). Nasjonalatlas for Norge: Vegetasjon. Hønefoss: Statens Kartverk. ISBN 9788290408263.

- "24-hr averages, 1961–90 base period". Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 2006-02-08.

- Tollefsrud, Jan Inge; Tjørve, Even; Hermansen, Pål (1991). Perler i Norsk Natur – En Veiviser. Aschehoug. ISBN 9788203166631.

- Almanakk for Norge. University of Oslo. 2010. ISBN 9788205394735.