Noah

Noah[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈnoʊ.ə/)[3] appears as the last of the Antediluvian patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baha'i writings. Noah is referenced in various other books of the Bible, including the New Testament, and in associated deuterocanonical books.

Noah | |

|---|---|

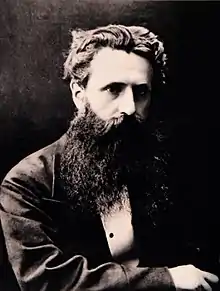

Noah's Sacrifice by Daniel Maclise | |

| Venerated in | Judaism Mandaeism Christianity Druze faith[1][2] Yazidism Islam Baháʼí Faith |

| Major shrine | on a hill at Karak, Lebanon |

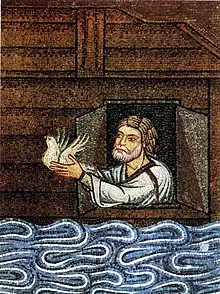

The Genesis flood narrative is among the best-known stories of the Bible. In this account, Noah labored faithfully to build the Ark at God's command, ultimately saving not only his own family, but mankind itself and all land animals, from extinction during the Flood, which God created after regretting that the world was full of sin. Afterwards, God made a covenant with Noah and promised never again to destroy all the Earth's creatures with a flood. Noah is also portrayed as a "tiller of the soil" and as a drinker of wine. After the flood, God commands Noah and his sons to "be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth".

Biblical narrative

Tenth and final of the pre-Flood (antediluvian) Patriarchs, son to Lamech and an unnamed mother,[4] Noah is 500 years old before his sons Shem, Ham and Japheth are born.[5]

Genesis flood narrative

The Genesis flood narrative is encompassed within chapters 6–9 in the Book of Genesis, in the Bible.[6] The narrative indicates that God intended to return the Earth to its pre-Creation state of watery chaos by flooding the Earth because of humanity's misdeeds and then remake it using the microcosm of Noah's ark. Thus, the flood was no ordinary overflow but a reversal of Creation.[7] The narrative discusses the evil of mankind that moved God to destroy the world by way of the flood, the preparation of the ark for certain animals, Noah, and his family, and God's guarantee (the Noahic Covenant) for the continued existence of life under the promise that he would never send another flood.[8]

After the flood

After the flood, Noah offered burnt offerings to God. God accepted the sacrifice, and made a covenant with Noah, and through him with all mankind, that he would not waste the earth or destroy man by another deluge.[5]

"And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth".[9] As a pledge of this gracious covenant with man and beast the rainbow was set in the clouds (ib. viii. 15–22, ix. 8–17). Two injunctions were laid upon Noah: While the eating of animal food was permitted, abstinence from blood was strictly enjoined; and the shedding of the blood of man by man was made a crime punishable by death at the hands of man (ib. ix. 3–6).[10]

Noah, as the last of the extremely long-lived Antediluvian patriarchs, died 350 years after the flood, at the age of 950, when Terah was 128.[5] The maximum human lifespan, as depicted by the Bible, gradually diminishes thereafter, from almost 1,000 years to the 120 years of Moses.[11][12]

Noah's drunkenness

After the flood, the Bible says that Noah became a farmer and he planted a vineyard. He drank wine made from this vineyard, and got drunk; and lay "uncovered" within his tent. Noah's son Ham, the father of Canaan, saw his father naked and told his brothers, which led to Ham's son Canaan being cursed by Noah.[10]

As early as the Classical era, commentators on Genesis 9:20–21[13] have excused Noah's excessive drinking because he was considered to be the first wine drinker; the first person to discover the effects of wine.[14] John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, and a Church Father, wrote in the 4th century that Noah's behavior is defensible: as the first human to taste wine, he would not know its effects: "Through ignorance and inexperience of the proper amount to drink, fell into a drunken stupor".[15] Philo, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher, also excused Noah by noting that one can drink in two different manners: (1) to drink wine in excess, a peculiar sin to the vicious evil man or (2) to partake of wine as the wise man, Noah being the latter.[16] In Jewish tradition and rabbinic literature on Noah, rabbis blame Satan for the intoxicating properties of the wine.[17][10]

In the context of Noah's drunkenness,[18] relates two facts: (1) Noah became drunken and "he was uncovered within his tent", and (2) Ham "saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without".[19][20]

Because of its brevity and textual inconsistencies, it has been suggested that this narrative is a "splinter from a more substantial tale".[21][22] A fuller account would explain what exactly Ham had done to his father, or why Noah directed a curse at Canaan for Ham's misdeed, or how Noah realised what had occurred. In the field of psychological biblical criticism, J. H. Ellens and W. G. Rollins have analysed the unconventional behavior that occurs between Noah and Ham as revolving around sexuality and the exposure of genitalia as compared with other Hebrew Bible texts, such as Habakkuk 2:15[23] and Lamentations 4:21.[24][19]

Other commentaries mention that "uncovering someone's nakedness" could mean having sexual intercourse with that person or that person's spouse, as quoted in Leviticus 18:7–8[25] and 20.[26] From this interpretation comes the speculation that Ham was guilty of engaging in incest and raping Noah[27] or his own mother. The latter interpretation would clarify why Canaan, as the product of this illicit union, was cursed by Noah.[20] Alternatively, Canaan could be the perpetrator himself as the Bible describes the illicit deed being committed by Noah's "youngest son", with Ham being consistently described as the middle son in other verses.[28]

Table of nations

Genesis 10[29] sets forth the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, from whom the nations branched out over the Earth after the flood. Among Japheth's descendants were the maritime nations (10:2–5). Ham's son Cush had a son named Nimrod, who became the first man of might on earth, a mighty hunter, king in Babylon and the land of Shinar (10:6–10). From there Ashur went and built Nineveh. (10:11–12) Canaan's descendants – Sidon, Heth, the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites – spread out from Sidon as far as Gerar, near Gaza, and as far as Sodom and Gomorrah (10:15–19). Among Shem's descendants was Eber (10:21).

These genealogies differ structurally from those set out in Genesis 5 and 11. It has a segmented or treelike structure, going from one father to many offspring. It is strange that the table, which assumes that the population is distributed about the Earth, precedes the account of the Tower of Babel, which says that all the population is in one place before it is dispersed.[30]

Family tree

Genesis 5:1–32 transmits a genealogy of the Sethites down to Noah, which is taken from the priestly tradition.[31] A genealogy of the Canites from the Jawhistic tradition is found in Genesis 4:17–26.[32] Biblical scholars see these as variants on one and the same list.[33] However, if we take the merged text of Genesis as a single account, we can construct the following family tree, which has come down in this form into the Jewish and Christian traditions.

- Hebrew: נֹחַ, Modern: Nōaẖ, Tiberian: Nōaḥ; Syriac: ܢܘܚ Nukh; Amharic: ኖህ, Noḥ; Arabic: نُوح Nūḥ; Ancient Greek: Νῶε Nôe

- Genesis 4:1

- Genesis 4:2

- Genesis 4:25; 5:3

- Genesis 4:17

- Genesis 4:26; 5:6–7

- Genesis 4:18

- Genesis 5:9–10

- Genesis 5:12–13

- Genesis 5:15–16

- Genesis 4:19

- Genesis 5:18–19

- Genesis 4:20

- Genesis 4:21

- Genesis 4:22

- Genesis 5:21–22

- Genesis 5:25–26

- Genesis 5:28–30

- Genesis 5:32

Narrative analysis

According to the documentary hypothesis, the first five books of the Bible (Pentateuch/Torah), including Genesis, were collated during the 5th century BC from four main sources, which themselves date from no earlier than the 10th century BC. Two of these, the Jahwist, composed in the 10th century BC, and the Priestly source, from the late 7th century BC, make up the chapters of Genesis which concern Noah. The attempt by the 5th-century editor to accommodate two independent and sometimes conflicting sources accounts for the confusion over such matters as how many of each animal Noah took, and how long the flood lasted.[34][35]

The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Books of the Bible notes that this story echoes parts of the Garden of Eden story: Noah is the first vintner, while Adam is the first farmer; both have problems with their produce; both stories involve nakedness; and both involve a division between brothers leading to a curse. However, after the flood, the stories differ. It is Noah, not God, who plants the vineyard and utters the curse, so "God is less involved".[36]

Other accounts

In addition to the main story in Genesis, the Hebrew Bible (Christian Old Testament) also refers to Noah in the First Book of Chronicles, Isaiah and Ezekiel. References in the deuterocanonical books include the books of Tobit, Wisdom, Sirach, 2 Esdras and 4 Maccabees. New Testament references include the gospels of Matthew and Luke, and some of the epistles (Epistle to the Hebrews, 1 Peter and 2 Peter).

Noah became the subject of much elaboration in the literature of later Abrahamic religions, including Islam (Surahs 71, 7, 11, 54, and 21 of the Quran) and Baháʼí faith (Kitáb-i-Íqán and Gems of Divine Mysteries).[37][38]

Pseudepigrapha

The Book of Jubilees refers to Noah and says that he was taught the arts of healing by an angel so that his children could overcome "the offspring of the Watchers".[39]

In 10:1–3 of the Book of Enoch (which is part of the Orthodox Tewahedo biblical canon) and canonical for Beta Israel, Uriel was dispatched by "the Most High" to inform Noah of the approaching "deluge".[40]

Dead Sea scrolls

There are 20 or so fragments of the Dead Sea scrolls that appear to refer to Noah.[41] Lawrence Schiffman writes, "Among the Dead Sea Scrolls at least three different versions of this legend are preserved."[42] In particular, "The Genesis Apocryphon devotes considerable space to Noah." However, "The material seems to have little in common with Genesis 5 which reports the birth of Noah." Also, Noah's father is reported as worrying that his son was actually fathered by one of the Watchers.[43]

Religious views

Judaism

The righteousness of Noah is the subject of much discussion among rabbis.[10] The description of Noah as "righteous in his generation" implied to some that his perfection was only relative: In his generation of wicked people, he could be considered righteous, but in the generation of a tzadik like Abraham, he would not be considered so righteous. They point out that Noah did not pray to God on behalf of those about to be destroyed, as Abraham prayed for the wicked of Sodom and Gomorrah. In fact, Noah is never seen to speak; he simply listens to God and acts on his orders. This led some commentators to offer the figure of Noah as "the righteous man in a fur coat," who ensured his own comfort while ignoring his neighbour.[44] Others, such as the medieval commentator Rashi, held on the contrary that the building of the Ark was stretched over 120 years, deliberately in order to give sinners time to repent. Rashi interprets his father's statement of the naming of Noah (in Hebrew – Noaħ נֹחַ) "This one will comfort us (in Hebrew– yeNaĦamenu יְנַחֲמֵנו) in our work and in the toil of our hands, which come from the ground that the Lord had cursed",[45] by saying Noah heralded a new era of prosperity, when there was easing (in Hebrew – naħah – נחה) from the curse from the time of Adam when the Earth produced thorns and thistles even where men sowed wheat and that Noah then introduced the plow.[46]

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "The Book of Genesis contains two accounts of Noah." In the first, Noah is the hero of the flood, and in the second, he is the father of mankind and a husbandman who planted the first vineyard. "The disparity of character between these two narratives has caused some critics to insist that the subject of the latter account was not the same as the subject of the former."[10]

The Encyclopedia Judaica notes that Noah's drunkenness is not presented as reprehensible behavior. Rather, "It is clear that ... Noah’s venture into viticulture provides the setting for the castigation of Israel’s Canaanite neighbors." It was Ham who committed an offense when he viewed his father's nakedness. Yet, "Noah’s curse, ... is strangely aimed at Canaan rather than the disrespectful Ham."[47]

Mandaeism

In Mandaeism, Noah (Classical Mandaic: ࡍࡅ) is mentioned in Book 18 of the Right Ginza. In the text, Noah's wife is named as Nuraita (Classical Mandaic: ࡍࡅࡓࡀࡉࡕࡀ), while his son is named as Shum (i.e., Shem; Classical Mandaic: ࡔࡅࡌ).[48][49]

Christianity

2 Peter 2:5 refers to Noah as a "preacher of righteousness".[50] In the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke, Jesus compares Noah's flood with the coming Day of Judgement: "Just as it was in the days of Noah, so too it will be in the days of the coming of the Son of Man. For in the days before the flood, people were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, up to the day Noah entered the ark; and they knew nothing about what would happen until the flood came and took them all away. That is how it will be at the coming of the Son of Man."[51][52]

The First Epistle of Peter compares the power of baptism with the Ark saving those who were in it. In later Christian thought, the Ark came to be compared to the Church: salvation was to be found only within Christ and his Lordship, as in Noah's time it had been found only within the Ark. St Augustine of Hippo (354–430), demonstrated in The City of God that the dimensions of the Ark corresponded to the dimensions of the human body, which corresponds to the body of Christ; the equation of Ark and Church is still found in the Anglican rite of baptism, which asks God, "who of thy great mercy didst save Noah," to receive into the Church the infant about to be baptised.[53]

In medieval Christianity, Noah's three sons were generally considered as the founders of the populations of the three known continents, Japheth/Europe, Shem/Asia, and Ham/Africa, although a rarer variation held that they represented the three classes of medieval society – the priests (Shem), the warriors (Japheth), and the peasants (Ham). In medieval Christian thought, Ham was considered to be the ancestor of the people of black Africa. So, in racialist arguments, the curse of Ham became a justification for the slavery of the black races.[54]

Isaac Newton, in his religious works on the development of religion, wrote about Noah and his offspring. In Newton's view, while Noah was a monotheist, the gods of pagan antiquity are identified with Noah and his descendants.[55]

Gnosticism

An important Gnostic text, the Apocryphon of John, reports that the chief archon caused the flood because he desired to destroy the world he had made, but the First Thought informed Noah of the chief archon's plans, and Noah informed the remainder of humanity. Unlike the account of Genesis, not only are Noah's family saved, but many others also heed Noah's call. There is no ark in this account. According to Elaine Pagels, "Rather, they hid in a particular place, not only Noah, but also many other people from the unshakable race. They entered that place and hid in a bright cloud."[56]

Druze faith

The Druze regard Noah as the second spokesman (natiq) after Adam, who helped transmit the foundational teachings of monotheism (tawhid) intended for the larger audience.[57] He is considered an important prophet of God among Druze, being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[1][2]

Islam

Noah is a highly important figure in Islam and he is seen as one of the most significant of all prophets. The Quran contains 43 references to Noah, or Nuḥ, in 28 chapters, and the seventy-first chapter, Sūrah Nūḥ (Arabic: سورة نوح), is named after him. His life is also spoken of in the commentaries and in Islamic legends.

Noah's narratives largely cover his preaching as well the story of the Deluge. Noah's narrative sets the prototype for many of the subsequent prophetic stories, which begin with the prophet warning his people and then the community rejecting the message and facing a punishment.

Noah has several titles in Islam, based primarily on praise for him in the Quran, including "Trustworthy Messenger of God" (26:107) and "Grateful Servant of God" (17:3).[47][58]

The Quran focuses on several instances from Noah's life more than others, and one of the most significant events is the Flood. God makes a covenant with Noah just as he did with Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Muhammad later on (33:7). Noah is later reviled by his people and reproached by them for being a mere human messenger and not an angel (10:72-74). Moreover, the people mock Noah's words and call him a liar (7:62), and they even suggest that Noah is possessed by a devil when the prophet ceases to preach (54:9). Only the lowest in the community join Noah in believing in God's message (11:29), and Noah's narrative further describes him preaching both in private and public. The Quran narrates that Noah received a revelation to build an Ark, after his people refused to believe in his message and hear the warning. The narrative goes on to describe that waters poured forth from both the earth and the Heavens, destroying all the sinners. Even one of his sons disbelieved him, stayed behind, and was drowned. After the Flood ended, the Ark rested atop Mount Judi (Quran 11:44).

Also, Islamic beliefs deny the idea of Noah being the first person to drink wine and experience the aftereffects of doing so.[47][58]

Quran 29:14 states that Noah had been living among the people who he was sent to for 950 years when the flood started.

Indeed, We sent Noah to his people, and he remained among them for a thousand years, less fifty. Then the Flood overtook them, while they persisted in wrongdoing.

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith regards the Ark and the Flood as symbolic.[59] In Baháʼí belief, only Noah's followers were spiritually alive, preserved in the ark of his teachings, as others were spiritually dead.[60][61] The Baháʼí scripture Kitáb-i-Íqán endorses the Islamic belief that Noah had a large number of companions, either 40 or 72, besides his family on the Ark, and that he taught for 950 (symbolic) years before the flood.[62]

Ahmadiyya

According to the Ahmadiyya understanding of the Quran, the period described in the Quran is the age of his dispensation, which extended until the time of Ibrahim (Abraham, 950 years). The first 50 years were the years of spiritual progress, which were followed by 900 years of spiritual deterioration of the people of Noah.[63]

Comparative mythology

Indian and Greek flood-myths also exist, although there is little evidence that they were derived from the Mesopotamian flood-myth that underlies the biblical account.[64]

Mesopotamian

The Noah story of the Pentateuch is quite similar to a flood story contained in the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, composed c. 1800 BCE. In the Gilgamesh version, the Mesopotamian gods decide to send a great flood to destroy mankind. Various correlations between the stories of Noah and Gilgamesh (the flood, the construction of the ark, the salvation of animals, and the release of birds following the flood) have led to this story being seen as the source for the story of Noah. The few variations include the number of days of the deluge, the order of the birds, and the name of the mountain on which the ark rests. The flood story in Genesis 6–8 matches the Gilgamesh flood myth so closely that "few doubt that [it] derives from a Mesopotamian account."[65] What is particularly noticeable is the way the Genesis flood story follows the Gilgamesh flood tale "point by point and in the same order", even when the story permits other alternatives.[66]

The earliest written flood myth is found in the Mesopotamian Epic of Atrahasis and Epic of Gilgamesh texts. The Encyclopædia Britannica says "These mythologies are the source of such features of the biblical Flood story as the building and provisioning of the ark, its flotation, and the subsidence of the waters, as well as the part played by the human protagonist."[67] The Encyclopedia Judaica adds that there is a strong suggestion that "an intermediate agent was active. The people most likely to have fulfilled this role are the Hurrians, whose territory included the city of Harran, where the Patriarch Abraham had his roots. The Hurrians inherited the Flood story from Babylonia".[47] The encyclopedia mentions another similarity between the stories: Noah is the tenth patriarch and Berossus notes that "the hero of the great flood was Babylonia’s tenth antediluvian king." However, there is a discrepancy in the ages of the heroes. For the Mesopotamian antecedents, "the reigns of the antediluvian kings range from 18,600 to nearly 65,000 years." In the Bible, the lifespans "fall far short of the briefest reign mentioned in the related Mesopotamian texts." Also, the name of the hero differs between the traditions: "The earliest Mesopotamian flood account, written in the Sumerian language, calls the deluge hero Ziusudra."[47]

However, Yi Samuel Chen writes that the oldest versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh never mentioned the flood, just mentioning that he went to talk to Utnapishtim to find the secret of immortality. Starting with the Old Babylonian Period, there were attempts to syncretize Utnapishtim with Ziusudra, even though they were previously seen as different figures. Gilgamesh meeting the flood hero was first alluded to in the Old Babylonian Period in "The Death of Bilgamesh" and eventually was imported and standardized in the Epic of Gilgamesh probably in the Middle Babylonian Period.[68]

Gilgamesh’s historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2700 BC,[69] shortly before the earliest known written stories. The discovery of artifacts associated with Aga and Enmebaragesi of Kish, two other kings named in the stories, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh.[70]

The earliest Sumerian Gilgamesh poems date from as early as the Third dynasty of Ur (2100–2000 BC).[71] One of these poems mentions Gilgamesh’s journey to meet the flood hero, as well as a short version of the flood story, although Chen writes that his was included in texts written during the Old Babylonian Period.[68][72] The earliest Akkadian versions of the unified epic are dated to c. 2000–1500 BC.[73] Due to the fragmentary nature of these Old Babylonian versions, it is unclear whether they included an expanded account of the flood myth; although one fragment definitely includes the story of Gilgamesh’s journey to meet Utnapishtim. The "standard" Akkadian version included a long version of the flood story and was edited by Sin-liqe-unninni sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC.[74]

Yi Samuel Chen analyzes various texts from the Early Dynastic III Period through to the Old Babylonian Period, and argues that the flood narrative was only added in texts written during the Old Babylonian Period. When it comes to the Sumerian King List, observations by experts have always indicated that the portion of the Sumerian King List talking about before the flood is stylistically different from the King List Proper. Essentially Old Babylonian copies tend to represent a tradition of before the flood apart from the actual King List, whereas the Ur III copy of the King List and the duplicate from the Brockmon collection indicate that the King List Proper once existed independent of mention to the flood and the tradition of before the flood. Essentially, Chen gives evidence to prove that the section of before the flood and references to the flood in the Sumerian King List were all later additions added in during the Old Babylonian Period, as the Sumerian King List went through updates and edits. The Flood as a watershed in early History of the world was probably a new historiographical concept emerging in the Mesopotamian literary traditions during the Old Babylonian Period, as evident by the fact that the flood motif didn't show up in the Ur III copy and that earliest chronographical sources related to the flood show up in the Old Babylonian Period. Chen concludes that the name of Ziusudra as a flood hero and the idea of the flood hinted by that name in the Old Babylonian Version of "Instructions of Shuruppak" are only developments during that Old Babylonian Period, when also the didactic text was updated with information from the burgeoning Antediluvian Tradition[68]

Ancient Greek

Noah has often been compared to Deucalion, the son of Prometheus and Pronoia in Greek mythology. Like Noah, Deucalion is warned of the flood (by Zeus and Poseidon); he builds an ark and staffs it with creatures – and when he completes his voyage, gives thanks and takes advice from the gods on how to repopulate the Earth. Deucalion also sends a pigeon to find out about the situation of the world and the bird returns with an olive branch.[75][76] Deucalion, in some versions of the myth, also becomes the inventor of wine, like Noah.[77] Philo[78] and Justin equate Deucalion with Noah, and Josephus used the story of Deucalion as evidence that the flood actually occurred and that, therefore, Noah existed.[79][80]

The motif of a weather deity who headed the pantheon causing the great flood and then the trickster who created men from clay saving man is also present in Sumerian Mythology, as Enlil, instead of Zeus, causes the flood, and Enki, rather than Prometheus, saves man. Stephanie West has written that this is perhaps due to the Greeks borrowing stories from the Near East.[81]

See also

- Bergelmir, a jötunn in Norse mythology who survives the worldwide flood in a floating container

- Cessair, Noah's daughter in the Lebor Gabála Érenn who travels to Ireland with a fleet as instructed by Noah to try to escape the flood.

- Jamshid, character of the Shahnameh that has similarities with the story of Noah

- Manu, the central character in the Hindu flood myth, and Vishnu.

- Noah's wine, a term that refers to an alcoholic beverage.

- Noah's pudding

- Nu'u, a mythological Hawaiian character who built an ark and escaped a Great Flood.

- Patriarchal age

- Searches for Noah's Ark, sometimes referred to as arkeology.

- Seven Laws of Noah

- Sumerian flood myth (Eridu Genesis)

- Tomb of Noah

- Thamanin

Citations

- Hitti, Philip K. (1928). The Origins of the Druze People and Religion: With Extracts from Their Sacred Writings. Library of Alexandria. p. 37. ISBN 9781465546623.

- Dana, Nissim (2008). The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status. Michigan University press. p. 17. ISBN 9781903900369.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 9781405881180.

- Fullom, S.W. (1855). The History of Woman, and Her Connexion with Religion, Civilization, & Domestic Manners, from the Earliest Period. p.10

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bechtel, Florentine Stanislaus (1911). "Noe". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bechtel, Florentine Stanislaus (1911). "Noe". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Silverman, Jason (2013). Opening Heaven's Floodgates: The Genesis Flood Narrative, Its Context, and Reception. Gorgias Press.

- Barry L. Bandstra (2008). Reading the Old Testament: Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Cengage Learning. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-495-39105-0.

- Cotter 2003, pp. 49, 50.

- Genesis 9:1

- "NOAH - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com.

- Genesis 6:3

- Deuteronomy 31:22, 34:37

- Genesis 9:20–21

- Ellens & Rollins. Psychology and the Bible: From Freud to Kohut, 2004, (ISBN 027598348X, 9780275983482), p.52

- Hamilton, 1990, pp. 202–203

- Philo, 1971, p. 160

- Gen. Rabbah 36:3

- Genesis 9:18–27

- Ellens & Rollins, 2004, p.53

- John Sietze Bergsma/Scott Walker Hahn. 2005. "Noah's Nakedness and the Curse on Canaan". Journal Biblical Literature 124/1 (2005), p. 25-40.

- Speiser, 1964, 62

- T. A. Bergren. Biblical Figures Outside the Bible, 2002, (ISBN 1563384116, ISBN 978-1-56338-411-0), p. 136

- Habakkuk 2:15

- Lamentations 4:21

- Leviticus 18:7–8

- Leviticus 20:11

- Levenson, 2004, 26

- Kugel 1998, p. 223.

- Genesis 10

- Bandstra, B. (2008), Reading the Old Testament: Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Cengage Learning, pp. 67–68, ISBN 978-0495391050

- von Rad, Gerhard (1961). Genesis: A Commentary. London: SCM Press. pp. 67–73.

- von Rad, Gerhard (1961). Genesis: A Commentary. London: SCM Press. pp. 109–113.

- von Rad, Gerhard (1961). Genesis: A Commentary. London: SCM Press. p. 71.

- Collins, John J. (2004). Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-8006-2991-4.

- Friedman, Richard Elliotty (1989). Who Wrote the Bible?. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 0-06-063035-3.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Books of the Bible, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 318.

- "The Kitáb-i-Íqán | Bahá'í Reference Library". www.bahai.org. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- "Gems of Divine Mysteries | Bahá'í Reference Library". www.bahai.org. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- Lewis, Jack Pearl, A Study of the Interpretation of Noah and the Flood in Jewish and Christian Literature, BRILL, 1968, p. 14.

- . The Book of Enoch. translated by Robert H. Charles. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1917.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Peters, DM., Noah Traditions in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity, Society of Biblical Lit, 2008, pp. 15–17.

- Schiffman, LH., Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Volume 2, Granite Hill Publishers, 2000, pp. 613–614.

- Lewis, Jack Pearl, A Study of the Interpretation of Noah and the Flood in Jewish and Christian Literature, BRILL, 1968, p. 11. "the offspring of the Watchers"

- Mamet, D., Kushner, L., Five Cities of Refuge: Weekly Reflections on Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, Schocken Books, 2003, p. 1.

- Genesis 5:29

- Frishman, J., Rompay, L. von, The Book of Genesis in Jewish and Oriental Christian Interpretation: A Collection of Essays, Peeters Publishers, 1997, pp. 62–65.

- Young, Dwight (2007). "Noah". In Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael; Thomson Gale (Firm) (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 15 (2nd ed.). pp. 287–291. ISBN 978-0-02-865943-5. OCLC 123527471. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

The earliest Mesopotamian flood account, written in the Sumerian language, calls the deluge hero Ziusudra, which is thought to carry the connotation "he who laid hold on life of distant days."

- Gelbert, Carlos (2011). Ginza Rba. Sydney: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034630.

- Lidzbarski, Mark (1925). Ginza: Der Schatz oder Das große Buch der Mandäer. Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht.

- "Bibler.org – 2 Peter 2 (NASB)". February 28, 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-02-28.

- Matthew 24:38

- Luke 17:26

- Peters, DM., Noah Traditions in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity, Society of Biblical Lit, 2008, pp. 15–17.

- Jackson, JP., Weidman, NM., Race, Racism, and Science: Social Impact and Interaction, ABC-CLIO, 2004, p. 4.

- Force, J E (1999), "Essay 12: Newton, the "Ancients" and the "Moderns"", in Popkin, RH; Force, JE (eds.), Newton and Religion: Context, Nature, and Influence, International Archive of the History of Ideas, Kluwer, pp. 253–254, ISBN 9780792357445 – via Google Books

- Pagels, Elaine (2013). The Gnostic Gospels. Orion. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-78022-670-5.

- Swayd 2009, p. 3.

- Gibb, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1995). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: NED-SAM. Brill. pp. 108–109. ISBN 9789004098343.

- From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, October 28, 1949: Baháʼí News, No. 228, February 1950, p. 4. Republished in Compilation 1983, p. 508

- Poirier, Brent. "The Kitab-i-Iqan: The key to unsealing the mysteries of the Holy Bible". Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- Shoghi Effendi (1971). Messages to the Baháʼí World, 1950–1957. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 104. ISBN 0-87743-036-5.

- From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer, November 25, 1950. Published in Compilation 1983, p. 494

- Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry (2005). Hadhrat Nuh (PDF). Islam International Publications. ISBN 1-85372-758-X.

- Frazer, JG., in Dundes, A (ed.), The Flood Myth, University of California Press, 1988, pp. 121–122.

- George, A. R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-927841-1. Retrieved 8 November 2012 – via Google Books.

- Rendsburg, Gary. "The Biblical flood story in the light of the Gilgamesh flood account," in Gilgamesh and the world of Assyria, eds Azize, J & Weeks, N. Peters, 2007, p. 117

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Noah.

- Chen, Yi Samuel. The Primeval Flood Catastrophe: Origins and Early Development in Mesopotamian Traditions. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, pages 123, 502

- Dalley, Stephanie, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press (1989), p. 40–41

- Andrew George, page xix

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk.

- Andrew George, p. 101, "Early Second Millennium BC" in Old Babylonian

- Andrew George, pages xxiv–xxv

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Deucalion.

- Wajdenbaum, P., Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible, Routledge, 2014, pp. 104–108.

- Anderson, G., Greek and Roman Folklore: A Handbook, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. pp. 129–130.

- Lewis, JP.; Lewis, JP., A Study of the Interpretation of Noah and the Flood in Jewish and Christian Literature, BRILL, 1968, p. 47.

- Peters, DM., Noah Traditions in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity, Society of Biblical Lit, 2008, p. 4.

- Feldman, LH., Josephus's Interpretation of the Bible, University of California Press, 1998, p. 133.

- West, S. (1994). Prometheus Orientalized. Museum Helveticum, 51(3), 129–149.

General and cited references

- Alter, Robert (2008). The Five Books of Moses. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33393-0.

- Brett, Mark G. (2000). Genesis: Procreation and the Politics of Identity. Routledge. ISBN 978-0203992029.

- Compilation (1983), Hornby, Helen (ed.), Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File, Baháʼí Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India, ISBN 81-85091-46-3

- Dimant, Devorah (2001). "Noah in early Jewish literature". In Michael E. Stone; Theodore E. Bergren (eds.). Biblical Figures Outside the Bible. Trinity Press. ISBN 9781563384110.

- Freedman, Paul H. (1999). Images of the Medieval Peasant. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804733731.

- Goldenberg, David M. (2005). "What did Ham do to Noah?". In Stemberger, Günter; Perani, Mauro (eds.). The Words of a Wise Man's Mouth Are Gracious. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110188493.

- Goldenberg, David M. (2003). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691114651.

- Goldenberg, David M. (1997). "The Curse of Ham: A Case of Rabbinic Racism?". In Salzman, Jack; West, Cornel (eds.). Struggles in the Promised Land: Toward a History of Black-Jewish Relations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198024927.

- Goldenberg, David M. (2009). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400828548.

- Graves, Robert; Patai, Raphael (1964). Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis. Princeton University Press, Cassel.

- Ham, Ken; Sarfati, Jonathan; Wieland, Carl (2001). Batten, Don (ed.). "Are Black People the Result of a Curse on Ham". ChristianAnswers.net. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- Keil, Carl; Delitzsch, Franz (1885). Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament. Vol. 1. Trans. James Martin. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Kissling, Paul (2004). Genesis. Vol. 1. College Press. ISBN 9780899008752.

- Kugle, James L. (1998). Traditions of the Bible. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674791510.

- Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: Introduction and Annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-529751-5. (Levenson author note).

- Lulat, G (2005). A History of African Higher Education from Antiquity to the Present: A Critical Synthesis. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 85, 86. ISBN 9780313068669.

an ideologically driven misnomer...

- Metcalf, Alida C. (2005). Go-betweens and the Colonization of Brazil, 1500–1600 (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0292712768.

- Reeve, W. Paul (2015). Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975407-6.

- Robertson, John M. (1910). Christianity and Mythology. Kessinger Publishing (2004 reprint). p. 496. ISBN 978-0-7661-8768-9.

- Sadler, R.S. (2005). Can a Cushite Change his Skin?. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567029607.

- Sarna, Nahum (1981). "The Anticipatory Use of Information as a Literary Feature of the Genesis Narratives". In Friedman, Richard Elliott (ed.). The Creation of Sacred Literature: Composition and Redaction of the Biblical Text. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09637-0.

- Trost, Travis D. (2010). Who should be king in Israel?. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 9781433111518.

- VanderKam, James Claire (1980). "The Righteousness of Noah". In John Joseph Collins; George W. E. Nickelsburg (eds.). Ideal figures in ancient Judaism: profiles and paradigms, Volumes 12–15. Chico: Scholars Press. pp. 13–32. ISBN 978-0891304340. Retrieved 1 December 2013. VanderKam-Vitae

- Van Seters, John (2000). "Geography as an evaluative tool". In VanderKam, James (ed.). From Revelation to Canon: Studies in the Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Literature. Brill. ISBN 0391041363.

- Whitford, David M. (2009). The curse of Ham in the Early Modern Era. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754666257.

- Swayd, Samy S. (2009). The a to Z of the Druzes. ISBN 9780810868366.

External links

- "Noah" from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia

- "Nuh"—MuslimWiki

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 722.