Aga of Kish

Aga (Sumerian:𒀝𒂵)[2] commonly known as Aga of Kish, was the twenty-third and last king in the first dynasty of Kish during the Early Dynastic I period.[3][4] He is listed in the Sumerian King List and many sources as the son of Enmebaragesi.[5][6][7] The Kishite king ruled the city at its peak, probably reaching beyond the territory of Kish, including Umma and Zabala.[1]

| Aga 𒀝𒂵 | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| King of the First dynasty of Kish | |

| Reign | EDI (2900-2700 BC) |

| Predecessor | Enmebaragesi |

| Successor | End of Kishite hegemony Gilgamesh (Uruk Dynasty) |

| Father | Enmebaragesi |

The Sumerian poem Gilgamesh and Aga records the Kishite siege of Uruk after its lord Gilgamesh refused to submit to Aga, ending in Aga's defeat and consequently the fall of Kish's hegemony.[8]

Name

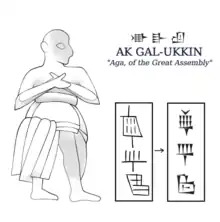

The name of Aga is Sumeriana and a relatively rarely attested personal name in Early Dynastic times, making his identification in royal texts spottable.[9] His name appears in the Stele of Ushumgal, as the gal-ukkin ("Great Assembly official").b

AK (𒀝) was likely an Early Dynastic spelling of Akka, (the past particle of the Sumerian verb "to make").[10] The name in question is to be interpreted as a Sumerian genitival phrase, Akka probably means "Made by [a god]" (ak + Divine Name.ak).[11]

| Cuneiform | Transliteration | Main inscription | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| 𒀝 | Ag/Ak |

Stele of Ushumgal Gem of King Aga |

2900-2700 BC |

| 𒀝𒂵 | Ag-ga/Ak-ka |

1900–1600 BC | |

| 𒀝𒃷 | Ag-ga3/Ak-ka3 |

1900–1600 BC |

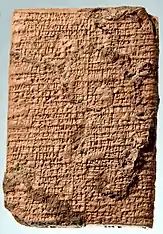

Historical king

Aga is attested in two compositions of an historiographical nature, the Sumerian King List and the Tummal Inscription, both as the son of Enmebaragesi, who has been verified through archaeological inscriptions; these sources may confirm Aga and Gilgamesh's existence.[15][16] Aga's name appears in the Stele of Ushumgal and the Gem of King Aga, both showing influence over Umma.[1]

Enmebaragesi,

the king in this very city (Nippur),

built the House of Enlil,

Agga the son of Enmebaragesi,

made the Tummal pre-eminent.

Reign

According to the Sumerian King List (ETCSL 2.1.1), Kish had the hegemony of Sumer where he reigned 625 years, succeeding his father Enmebaragesi to the throne, finally ending in defeat by Uruk.[6]

The use of the royal title King of Kish expressing a claim of national rulership owes its prestige to the fact that Kish once did rule the entire nation.[18] His reign probably covered Umma, and consequently Zabala, which was a dependent of it in the Early Dynastic Period; this can be supported on his appearance in the Gem of King Aga, where he is mentioned as the king of Umma.[1] There is some scant evidence to suggest that like the later Ur III kings, the rulers of ED Kish sought to ingratiate themselves to the authorities in Nippur, possibly to legitimize a claim for leadership over the land of Sumer or at least part of it.[1] Archeological evidence from Kish shows a city flourishing in ED II with its political influence extending beyond the territory, however in ED III the city declined rapidly.[19]

Gilgamesh and Aga

In the poem Gilgamesh and Aga (ETCSL 1.8.1.1), Aga of Kish sends messengers to his vassal Gilgamesh[20] in Uruk with a demand slave labor for the irrigation of Kish.[21][22]

There are wells to be finished.

There are wells in the land to be finished.

There are shallow wells in the land to be completed.

There are deep wells and hoisting ropes to be completed.— Aga commanding Uruk to work for the irrigation of Kish.

Gilgamesh repeats the message before the "city fathers" (ab-ba-iri) to suggest defiance of Aga, but the elders refuse. Gilgamesh, goes on to incite rebellion among the guruš (able-bodied men) who would have to do the labor. They refer to Aga as the "son of the king", which suggests he was still young and immature.[23] The guruš accept Gilgamesh's call to revolt and declare him lugal (king).c

After ten days, Aga lays siege to the walls of Uruk, whose citizens are now confused and intimidated. Gilgamesh asks for a volunteer to stand before Aga; his royal guard Birhurtura offers himself. On leaving the city gates, he is captured and brought before Aga, who interrogates and tortures him. Aga asks an Uruk soldier leaning over the wall if Birhurtura is his king. Birhurtura denies this, replying that when the true king appears, he will beat capture Aga and beat his army to dust. The infuriated Aga redoubles his torture.

Then Gilgamesh leans over the wall. Aga withstands his divine radiance, but it terrifies the Kishite army. Enkidu and the guruš take advantage of their confusion to cut through them and capture Aga in the middle of his army. Gilgamesh addresses Aga as his superior, remembering how Aga saved his life and gave him refuge; Aga withdraws his demand and begs his favor to be returned. Gilgamesh, in the sight of his god Utu, sets Aga free to return to Kish.[24]

Replacement in the poem

The Shulgi Hymn O (ETCSL 2.1.1) of the Ur III ruler Shulgi (c. 2094 BC – 2047 BC) praises Gilgamesh for defeating Enmebaragesi of Kish rather than his son. While such an encounter is quite conceivable,d the assumption of two different wars is difficult to uphold because Gilgamesh emerges as victorious in both; his first victory would have left Kish already defeated, pre-empting the second victory.[25] If Gilgamesh had won a previous war against Kish, he would not have spoken with Aga of past military cooperation and indebtedness for saving his life.

Another theory is that for literary considerations, the founding hegemon Enmebaragesi would be a more impressive opponent than his son. Enmebaragesi was merely inserted to replace Aga, and the different versions of the hymn constitute to a single literary work.[26]

Notes

Citations

- Faryne "The Struggle for Hegemony in Early Dynastic II Sumer" The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies pp.65-66

- "Sumerian Dictionary "Aga" (RN) entry". Upenn.edu.

- Beaulieu A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75 p.36

- Kramer (1963) The Sumerians: their history, culture, and character p.49

- Jacobsen The Sumerian King List p.83

- Sumerian King List (ETCSL 2.1.1)

- Kuhrt The Ancient Near East, C. 3000-330 BC, Volume 1 p.29

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.10

- Selz (2003) p. 506

- "Epsd2".

- Sallaberger Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia p.149

- Selz (2003) p. 510

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- George The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts p.105

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.13

- Sollberger (1962) p. 40-47

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.30 n.83

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.16

- Keetman. Akka von Kiš und die Arbeitsverweigerer p.17

- W.G Lambert (1980) p.339-340

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.17

- Keetman. Akka von Kiš und die Arbeitsverweigerer p.19

- George The epic of Gilgamesh: a new translation p.148

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.14

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.15

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.20

- Fleming (2009) p.209

- Katz Gilgamesh and Akka p.29

References

- Faryne, Douglas (2009). "The Struggle for Hegemony in "Early Dynastic II" Sumer". The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies. IV: 65–66.

- Beaulieu, Paul Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75 (First ed.). Wiley Blackway. ISBN 978-111-945-9071.

- Katz, Dina (1993). Gilgamesh and Akka (First ed.). Groningen, the Netherlands: SIXY Publication. ISBN 90-72371-67-4.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1939). Sumerian King List (Second ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226622736.

- Sallaberger, Walther (2015). Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia (First ed.). Brepols Publishers. ISBN 978-2-503-53494-7.

- George, A.R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts (First ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927841-1.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: their history, culture, and character (First ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

- Fleming, Daniel E. (2000). Time at Emar: The Cultic Calendar and the Rituals from the Diviner's Archive (First ed.). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-044-6.

- George, Andrew (1999). The Epic of Gilgamesh: A new translation (First ed.). Penguin classics. ISBN 0-14-044721-0.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1999). The Ancient Near East, C. 3000-330 BC, Volume 1 (First ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01353-4.

- Keetman, Jan (2012). "Akka von Kiš und die Arbeitsverweigerer". Babel und Bibel:Annual of Ancient Near Eastern, Old Testament, and Semitic Studies. VI.

- Selz, G (2003). "Who is who? Aka, King of Giš(š)a: on the historicity of a king and his possible identity with Aka, King of Kiš". Old Orient and Old Testament (274).

- Sollberger, E (1962). "The Tummal Inscription". JCS (16).

- W.G, Lambert (1980). "Akka's threat". OrNS (40).