Ur-Nammu

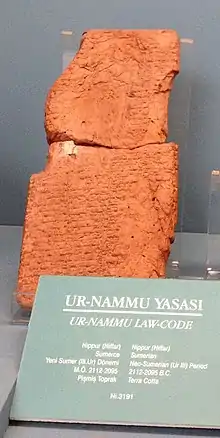

Ur-Nammu (or Ur-Namma, Ur-Engur, Ur-Gur, Sumerian: 𒌨𒀭𒇉, ruled c. 2112 BC – 2094 BC middle chronology, or possibly c. 2048–2030 BC short chronology) founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries of Akkadian and Gutian rule. His main achievement was state-building, and Ur-Nammu is chiefly remembered today for his legal code, the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving example in the world. He held the titles of "King of Ur, and King of Sumer and Akkad".

| Ur-Nammu 𒌨𒀭𒇉 | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of the Neo-Sumerian Empire | |

| Reign | c. 2112 BC – 2094 BC

(Middle Chronology) c. 2048 BC – 2030 BC (Short Chronology) |

| Predecessor | Utu-hengal |

| Successor | Shulgi |

| Consort | Watartum |

| Issue | Shulgi |

| Dynasty | 3rd Dynasty of Ur |

| Religion | Sumerian religion |

.jpg.webp)

𒀭𒈹 Dinanna.... "For Inanna-"

𒎏𒂍𒀭𒈾 Nin-e-an-na.... "Ninanna,"

𒎏𒀀𒉌 NIN-a-ni.... "his Lady"

𒌨𒀭𒇉 UR-NAMMU.... "Ur-Nammu"

𒍑𒆗𒂵 NITAH KALAG ga.... "the mighty man"

𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠𒈠 LUGAL URIM KI ma.... "King of Ur"

𒈗𒆠𒂗𒄀𒆠𒌵𒆤 LUGAL ki en gi ki URI ke.... "King of Sumer and Akkad"

Reign

According to the Sumerian King List, Ur-Nammu reigned for 18 years.[4] Year-names are known for 17 of these years, but their order is uncertain. One year-name of his reign records the devastation of Gutium, while two years seem to commemorate his legal reforms ("Year in which Ur-Nammu the king put in order the ways (of the people in the country) from below to above", "Year Ur-Nammu made justice in the land").[5]

Among his military exploits were the conquest of Lagash and the defeat of his former masters at Uruk. He was eventually recognized as a significant regional ruler (of Ur, Eridu, and Uruk) at a coronation in Nippur, and is believed to have constructed buildings at Nippur, Larsa, Kish, Adab, and Umma. He was known for restoring the roads and general order after the Gutian period.[6] It is now known that the reign of Puzur-Inshushinak in Elam overlapped with that of Ur-Nammu.[7] Ur-Nammu, who styled himself "King of Sumer and Akkad" is probably the one who, in his reign, reconquered the territories of central and northern Mesopotamia that had been occupied by Puzur-Inshushinak, possibly at the expense of the Gutians, and conquered Susa.[8]

Ur-Nammu was also responsible for ordering the construction of a number of ziggurats, including the Great Ziggurat of Ur.[9]

He was killed in a battle against the Gutians after he had been abandoned by his army.[6] Ur-Nammu's death in battle was commemorated in a long Sumerian elegiac composition, "The Death of Ur-Nammu".[6][10][11] He was succeeded by his son Shulgi.[4] The king seems to have married family members to important people all over the empire to secure loyalty in provinces. One example is his daughter Simat-Ištaran, who was married to a local general.[12]

Deification debate

Ur-Nammu is notable for having been one of the few Mesopotamian kings of the third millennium BC who was not deified after his death.[13] This is testified by the posthumous Sumerian literature which never includes the divine determinative before Ur-Nammu's name (this can be seen on the transliterations for the texts on ETCSL), the themes of divine abandonment in "The Death of Ur-Nammu", and the fact that Shulgi promoted his lineage to members of the legendary Uruk dynasty as opposed to Ur-Nammu.[14] While some translations of Sumerian texts had included the divine determinative before Ur-Nammu's name[4] more recent evidence indicates this was a mistaken addition.[15] Despite this, the belief that the king was deified after death has been expressed just as recently, demonstrating a lack of certainty on this issue (though these were written during the same year as the new interpretations of the evidence and thus could not refer to them).[16] Sharlach has more recently noted that favour for Ur-Nammu not having been deified has been accepted by many scholars.[13]

Year names of Ur-Nammu

Several of the year names of Ur-Nammu are known, documenting the major events of his reign. The main year names are:

- "Ur-Namma (is) King"

- "Ur-Namma declared an amnesty (misharum) in the land"

- "The wall of Ur was built"

- "The king received kingship from Nippur"

- "The temple of Nanna was built"

- "The 'A-Nintu' canal was dug"

- "The land of Guti was destroyed"

- "The god Lugal-bagara was brought into his temple"[17]

Artifacts

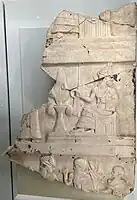

.jpg.webp)

Ur Namma stele detail, Penn Museum.

Ur Namma stele detail, Penn Museum.

Fired mudbrick, stamped. The cuneiform inscription mentions the name of Ur-Nammu, and there are two presumably accidentally impressed dog's paw-marks near one edge. From the Ziggurat of Ur, Ur, Iraq. Ur III period, 21st century BC. British Museum

Fired mudbrick, stamped. The cuneiform inscription mentions the name of Ur-Nammu, and there are two presumably accidentally impressed dog's paw-marks near one edge. From the Ziggurat of Ur, Ur, Iraq. Ur III period, 21st century BC. British Museum Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu. British Museum.[20]

Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu. British Museum.[20].jpg.webp) Name of Ur-Nammu on a seal, and standard cuneiform

Name of Ur-Nammu on a seal, and standard cuneiform "Ur-Nammu, King of Ur, and King of Sumer and Akkad" (𒌨𒀭𒇉: Ur-Nammu 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠: Lugal Urimki 𒈠: ma 𒈗𒆠𒂗𒄀: Lugal Kiengir 𒆠𒌵: Kiuri)

"Ur-Nammu, King of Ur, and King of Sumer and Akkad" (𒌨𒀭𒇉: Ur-Nammu 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠: Lugal Urimki 𒈠: ma 𒈗𒆠𒂗𒄀: Lugal Kiengir 𒆠𒌵: Kiuri) Foundation figure in the form of a peg surmounted by the bust of King Ur-Nammu.

Foundation figure in the form of a peg surmounted by the bust of King Ur-Nammu.

See also

- Nammu: the god Ur-Nammu was named after.

Notes

- 𒌨𒀭𒇉 URDNAMMU / 𒍑𒆗𒂵 NITAH KALAG ga / 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠𒈠 LUGAL URIM KI ma.

- "Hash-hamer Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu". British Museum.

- Enderwitz, Susanne; Sauer, Rebecca (2015). Communication and Materiality: Written and Unwritten Communication in Pre-Modern Societies. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 28. ISBN 978-3-11-041300-7.

- Thorkild Jacobsen, The Sumerian King List (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939),pp. 122f

- Year-names for Ur-Nammu

- Hamblin, William J., Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC (New York: Routledge, 2006).

- Wilcke; See Encyclopedia Iranica articles AWAN, ELAM

- Steinkeller, Piotr. "Puzur-Inˇsuˇsinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered". Susa and Elam. Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives. Mémoires de la Délégation en Perse: 298–299.

- "The ziggurat (and temple?) of Ur-Nammu". Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- Shipp, R. Mark (2002). Of Dead Kings and Dirges: Myth and Meaning in Isaiah 14:4b-21. BRILL. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-90-04-12715-9.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). "The Death of Ur-Nammu and His Descent to the Netherworld". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 21: 104–122. doi:10.2307/1359365. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359365. S2CID 163757208.

- Steven J. Garfinkle: The Kingdom of Ur, in: Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts (Herausgeber): The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume II: Volume II: From the End of the Third Millennium BC to the Fall of Babylon, Oxford 2022, ISBN 978-0-19-068757-1, pp. 154–155.

- Sharlach, T.M. (2017). An Ox of One's Own: Royal Wives and Religion at the Court of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Boston/Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 15.

- Michalowski, Piotr (2008). Brisch, Nicole (ed.). "The Mortal Kings of Ur: A Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia". Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond: 36–7.

- Michalowski, Piotr (2008). Brisch, Nicole (ed.). "The Mortal Kings of Ur: A Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia". Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond: 35.

- Winter, Irene (2008). Brisch, Nicole (ed.). "Touched by the Gods: Visual Evidence for the Divine Status of Rulers in the Ancient Near East". Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond: 77.

- "Year names of Ur-Nammu". CDLI:wiki. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, Cambridge University. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- "The Stela of the Flying Angels". The Museum Journal.

- Legrain, Leon (1927). "The Stela of the Flying Angels" (PDF). The Museum Journal. Philadelphia. The University Museum. 18: 74-98.

- "Hash-hamer Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu". British Museum.

External links

- Site drawings of the temple built by Ur-Nammu at Ur to the moon god Nanna.

- Nabonidus dedication to the Ziggurat

- The Code of Ur-Nammu at Britannica

- Foundation Figurine of King Ur-Nammu at the Oriental Institute of Chicago

- The "Ur-Nammu" Stela. Penn Museum. 2006. ISBN 978-1-931707-89-3.

- The face of Ur-Namma. A realistic statue of Ur-Namma shows us how he may have looked.

- A brief description of the reign of Ur-Namma.

- I am Ur-Namma. The life and death of Ur-Namma, as told in Babylonian literature.