Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Re") was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2465 – c. 2325 BC). He reigned for about 13 years in the early 25th century BC during the Old Kingdom Period. Sahure's reign marks the political and cultural high point of the Fifth Dynasty.[28] He was probably the son of his predecessor Userkaf with Queen Neferhetepes II, and was in turn succeeded by his son Neferirkare Kakai.

| Sahure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sahura, Sahu-Re, Sephrês, Σϵϕρής | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Head of a gneiss statue of Sahure in the gallery 103 of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1][2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Duration: 13 years, 5 months and 12 days in the early 25th century BC[note 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Userkaf | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Neferirkare Kakai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Meretnebty[24] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Ranefer ♂ (ascended the throne as Neferirkare Kakai), Netjerirenre ♂ (possibly the same person as Shepseskare), Horemsaf ♂, Raemsaf ♂, Khakare ♂ and Nebankhre ♂[25][26] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Userkaf | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Neferhetepes II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Sahure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid of Sahure "The Rising of the Ba Spirit of Sahure"[27] Sun temple "The Field of Ra" Palaces "Sahure's splendor soars up to heaven" and "The crown of Sahure appears" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Fifth Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During Sahure's rule, Egypt had important trade relations with the Levantine coast. Sahure launched several naval expeditions to modern-day Lebanon to procure cedar trees, slaves and exotic items. His reign may have witnessed the flourishing of the Egyptian navy, which included a high-seas fleet as well as specialized racing boats. Relying on this, Sahure ordered the earliest attested expedition to the land of Punt, which brought back large quantities of myrrh, malachite and electrum. Sahure is shown celebrating the success of this venture in a relief from his mortuary temple which shows him tending a myrrh tree in the garden of his palace named "Sahure's splendor soars up to heaven". This relief is the only one in Egyptian art depicting a king gardening. Sahure sent further expeditions to the turquoise and copper mines in Sinai. He also ordered military campaigns against Libyan chieftains in the Western Desert, bringing back livestock to Egypt.

Sahure had a pyramid built for himself in Abusir, thereby abandoning the royal necropolises of Saqqara and Giza, where his predecessors had built their monuments. This decision was possibly motivated by the presence of the sun temple of Userkaf in Abusir, the first such temple of the Fifth Dynasty. The Pyramid of Sahure is much smaller than the pyramids of the preceding Fourth Dynasty but the decoration and architecture of his mortuary temple is more elaborate. The valley temple, causeway and mortuary temple of his pyramid complex were once adorned by over 10,000 m2 (110,000 sq ft) of exquisite polychrome reliefs, representing the highest form reached by this art during the Old Kingdom period. The Ancient Egyptians recognized this particular artistic achievement and tried to emulate the reliefs in the tombs of subsequent kings and queens. The architects of Sahure's pyramid complex introduced the use of palmiform columns (columns whose capital has the form of palm leaves), which would soon become a hallmark of ancient Egyptian architecture. The layout of his mortuary temple was also innovative and became the architectural standard for the remainder of the Old Kingdom period. Sahure is also known to have constructed a sun temple called "The Field of Ra", and although it is yet to be located it is presumably also in Abusir.

Sahure was the object of a funerary cult, the food offerings for which were initially provided by agricultural estates set up during his reign. This official, state-sponsored cult endured until the end of the Old Kingdom. Subsequently, during the Middle Kingdom period, Sahure was venerated as a royal ancestor figure but his cult no longer had dedicated priests. During the New Kingdom, Sahure was equated with a form of the goddess Sekhmet for unknown reasons. The cult of "Sekhmet of Sahure" had priests and attracted visitors from all over Egypt to Sahure's temple. This unusual cult, which was celebrated well beyond Abusir, persisted up until the end of the Ptolemaic period nearly 2500 years after Sahure's death.

Family

Parentage

Excavations at the pyramid of Sahure in Abusir under the direction of Miroslav Verner and Tarek El-Awady in the early 2000s provide a picture of the royal family of the early Fifth Dynasty. In particular, reliefs from the causeway linking the valley and mortuary temples of the pyramid complex reveal that Sahure's mother was queen Neferhetepes II.[29] She was the wife of pharaoh Userkaf, as indicated by the location of her pyramid immediately adjacent to that of Userkaf,[30] and bore the title of "king's mother".[note 2][31] This makes Userkaf the father of Sahure in all likelihood. This is further reinforced by the discovery of Sahure's cartouche in the mortuary temple of Userkaf at Saqqara, indicating that Sahure finished the structure started most probably by his father.[30]

This contradicts older, alternative theories according to which Sahure was the son of queen Khentkaus I,[32] believed to be the wife of the last pharaoh of the preceding Fourth Dynasty, Shepseskaf and a brother to either Userkaf or Neferirkare.[note 3][35]

Children

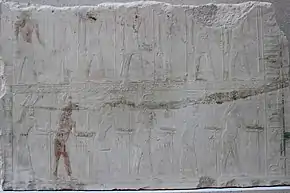

Sahure is known to have been succeeded by Neferirkare Kakai,[note 4] who until 2005 was believed to be his brother.[37] That year, a relief originally adorning the causeway of Sahure's pyramid and showing Sahure seated in front of two of his sons, Ranefer and Netjerirenre,[38] was discovered by Verner and another Egyptologist, Tarek El-Awady.[39] Next to Ranefer's name the text "Neferirkare Kakai king of Upper and Lower Egypt" had been added, indicating that Ranefer was Sahure's son and had assumed the throne under the name "Neferirkare Kakai" at the death of his father.[29] Since both Ranefer and Netjerirenre are given the titles of "king's eldest son", Verner and El-Awady speculate that they may have been twins with Ranefer born first. They propose that Netjerirenre may have later seized the throne for a brief reign under the name "Shepseskare", although this remains conjectural.[40] The same relief further depicts queen Meretnebty,[41] who was thus most likely Sahure's consort[42] and the mother of Ranefer and Netjerirenre.[39] Three more sons, Khakare,[43] Horemsaf,[44] and Nebankhre[45] are shown on reliefs from Sahure's mortuary temple, but the identity of their mother(s) is unknown.[24]

Netjerirenre bore several religious titles corresponding to high-ranking positions in the court and which suggest that he may have acted as a vizier for his father.[46] This is debated, as Michel Baud points out that at the time of Sahure, the eviction of royal princes from the vizierate was ongoing if not already complete.[47]

Reign

Chronology

Relative chronology

The relative chronology of Sahure's reign is well established by historical records, contemporary artifacts and archeological evidence, which agree that he succeeded Userkaf and was in turn succeeded by Neferirkare Kakai.[48] An historical source supporting this order of succession is the Aegyptiaca (Αἰγυπτιακά), a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II (283–246 BC) by Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus, Africanus wrote that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Usercherês → Sephrês → Nefercherês" at the start of the Fifth Dynasty. Usercherês, Sephrês (in Greek, Σϵϕρής), and Nefercherês are believed to be the Hellenized forms for Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare, respectively.[49] Manetho's reconstruction of the early Fifth Dynasty is in agreement with those given on two more historical sources, the Abydos king list where Sahure's cartouche is on the 27th entry, and the Saqqara Tablet where Sahure's name is given on the 33rd entry. These lists of kings were written during the reigns of Seti I and Ramses II, respectively.[50]

Reign length

The Turin canon, a king list written during the Nineteenth Dynasty in the early Ramesside era (1292–1189 BC), credits him with a reign of twelve years five months and twelve days. In contrast, the near contemporary royal annal of the Fifth Dynasty known as the Palermo Stone records his second, third, fifth and sixth years on the throne as well as his final 13th or 14th year of reign[note 5] and even records the day of his death as the 28th of Shemu I, which corresponds to the end of the ninth month.[55][56] Taken together these pieces of information indicate that the royal annal of the Fifth Dynasty recorded a reign of 13 years 5 months and 12 days for Sahure, only one year more than given by the Turin Canon and close to the 13 years figure given in Manetho's Aegyptiaca.[49]

Sahure appears in two further historical records: on the third entry of the Karnak king list, which was made during the reign of Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) and on the 26th entry of the Saqqara Tablet dating to the reign of Ramses II (1279–1213 BC).[12] Neither of these sources give his reign length. The absolute dates of Sahure's reign are uncertain but most scholars date it to the first half of the 25th century BC, see note 1 for details.[12]

Trade and tribute

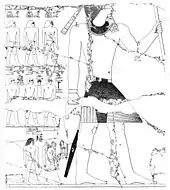

Historical records and surviving artifacts suggest that contacts with foreign lands were numerous during Sahure's reign. Furthermore, these contacts seem to have been mostly economic rather than military in nature. Reliefs from his pyramid complex show the return of a naval expedition to Lebanon, the boats laden with the trunks of precious cedar trees.[27] Other ships are represented loaded with "Asiatics",[note 6] both adults and children who were either slaves,[9][12][59] or merchants,[60] greeting Sahure:

Hail to thee, O Sahure! God of the living, we behold thy beauty!.[61]

The same relief strongly suggests that interpreters were on board the ships, tasked with translations to facilitate trade with foreign lands.[62] A relief, unique to Egyptian art, depicts several Syrian brown bears, presumably brought back from the Levantine coast by seagoing ships as well. These bears appear in association with 12 red-painted one-handled jars from Syria. The Egyptologists Karin Sowada and William Stevenson Smith have proposed that, taken together, the bears and jars are likely to constitute a tribute.[63][64]

Trade contacts with Byblos took place during Sahure's reign. Excavations of the temple of Baalat-Gebal yielded an alabaster bowl inscribed with Sahure's name.[12] The layout of the fourth phase of this temple might even have been influenced by the architecture of Sahure's valley temple,[note 7][67] although this remains debated.[68] There is further corroborating evidence for trade with the wider Levant during the Fifth Dynasty, several stone vessels being inscribed with cartouches of pharaohs of this dynasty discovered in Lebanon.[note 8][71] So much so that the archeologist Gregory Mumford points to the fact that "Sahure is [the] best attested [king] for international relations" and has the highest number of texts inscribed in Sinai proportionally to his reign length.[72]

In his last year, Sahure sent the first documented[73] expedition to the fabled land of Punt,[74] probably along the Somalian coast.[75] The expedition, which is conjectured to have departed Egypt from the harbor of Mersa Gawasis,[16] is reported on the Palermo Stone[6] where it is said to have come back with 80,000 of an unspecified measure of myrrh, along with malachite, 6000 measures of electrum and 2600 or 23,020 staves,[12][76] possibly made of ebony.[19] In his last year Sahure sent another expedition abroad, this time to the copper and turquoise mines of Wadi Maghareh[5][57][77] and Wadi Kharit in Sinai,[note 9][79][80] which had been active since at least the beginning of the Third Dynasty.[81] This expedition, also mentioned by the Palermo stone,[6] brought back over 6000 units of turquoise to Egypt[61] and produced two reliefs in Sinai, one of which shows Sahure in the traditional act of smiting Asiatics[12] and boasting "The Great God smites the Asiatics of all countries".[82] In parallel with these activities, diorite quarries near Abu Simbel were exploited throughout Sahure's reign.[75]

Military campaigns

Sahure's military career is known primarily from reliefs in his mortuary complex. It apparently consisted of campaigns against Libyans from Tjemehu, a land possibly located in the northern Western desert.[6] These campaigns are said to have yielded livestock in huge numbers[note 10] and Sahure is shown smiting local chieftains. The historical veracity of these depictions remains in doubt as such representations are part of the standard iconography meant to exalt the king.[6] The same scene of the Libyan attack was used two hundred years later in the mortuary temple of Pepi II (2284–2184 BC) and in the temple of Taharqa at Kawa, built some 1800 years after Sahure's lifetime.[86] In particular, the same names are quoted for the local chieftains. Therefore, it is possible that Sahure too was copying an even earlier representation of this scene.[87][88] Nonetheless, several overseers of the Western Nile Delta region were nominated by Sahure, a significant decision as these officials occupied an administrative position that existed only irregularly during the Old Kingdom period and which likely served to provide "traffic regulation across the Egypto-Libyan border".[89] At the same time, Sahure's mortuary temple presents the earliest known mention of pirates raiding the Nile Delta, possibly from the coast of Epirus.[90]

Sahure's pretensions regarding the lands and riches surrounding Egypt are encapsulated in several reliefs from his mortuary temple which show the god Ash telling the king "I will give you all that is in this [Libya] land", "I give you all hostile peoples with all the provisions that there are in foreign lands" and "I grant thee all western and eastern foreign lands with all the Iunti and the Montiu bowmen who are in every land".[note 11][91][61]

Religious activities

The majority of Sahure's activities in Egypt recorded on the Palermo stone are religious in nature. This royal annal records that in the "year of the first time of traveling around", Sahure journeyed to the Elephantine fortress, where he may have received the submission of the Nubian chiefs in a ceremonial act connected with the commencement of his reign.[92][93] The fashioning of six statues of the king as well as the subsequent opening of the mouth ceremonies are also reported.[94] During Sahure's fifth year on the throne, the Palermo stone mentions the making of a divine barge, possibly in Heliopolis, the appointment of 200 priests and the exact quantity of daily offerings of bread and beer to Ra (138, 40 and 74 measures in three temples), Hathor (4 measures), Nekhbet (800 measures) and Wadjet (4800 measures) fixed by the king.[95] Also reported are gifts of lands to temples of between 1 and 204 arouras (0.7 to nearly 140 acres).[82] Concerning Lower Egypt, the stone register corresponding to this reign gives the earliest known mention of the city of Athribis in the Delta region.[96]

Further indication of religious activities lies in that Sahure is the earliest known king to have used the Egyptian title of Nb írt-ḫt.[97] This title, possibly meaning "Lord of doing effective things", indicates that he personally performed physical cultic activities to ensure the existence and persistence of the Maat, the Egyptian concept of order and justice.[98] This title remained in use until the time of Herihor, some 1500 years later.[99] Sahure's reign is also the earliest during which the ceremony of the "driving of the calves" is known to have taken place. This is significant in the context of the progressive emergence of the cult of Osiris throughout the Fifth Dynasty, as this ceremony subsequently became an integral part of the Osiris myth. In subsequent times, the ceremony corresponded to Seth's threshing of Osiris by driving calves trampling fields of barley.[100]

Sahure reorganized the cult of his mother, Nepherhetepes II, whose mortuary complex had been built by Userkaf in Saqqara.[101] He added an entrance portico with four columns to her temple, so that the entrance was not facing Userkaf's pyramid any more.[101][102]

Building and mining activities

Archeological evidence suggests that Sahure's building activities were mostly concentrated in Abusir and its immediate vicinity, where he constructed his pyramid and where his sun temple is probably located.[103] Also nearby was the palace of Sahure, called Uetjes Neferu Sahure, "Sahure's splendor soars up to heaven". The palace is known from an inscription on beef tallow containers discovered in February 2011 in Neferefre's mortuary temple.[104] A second palace, "The Crown of Sahure appears", is known from an inscription in the tomb of his chief physician.[105] Both palaces, if they were different buildings, were likely on the shores of the Abusir lake.[106]

The stones for Sahure's buildings and statues were quarried throughout Egypt. For example, the limestone cladding of the pyramid comes from Tura, while the black basalt used for the flooring of Sahure's mortuary temple comes from Gebel Qatrani, near the Faiyum in Middle Egypt.[107] South of Egypt, a stele bearing Sahure's name was discovered in the diorite quarries located in the desert north-west of Abu Simbel in Lower Nubia.[108]

Further mining and quarrying expeditions may be inferred from indirect evidence. An inscription of Sahure in the Wadi Abu Geridah in the Eastern desert[109] as well as other Old Kingdom inscriptions there suggest that iron ore was mined in the vicinity since the times of the Fourth Dynasty.[110] The lower half of a statue with the name of the king was discovered in 2015 in Elkab, a location possibly connected with expeditions to the Eastern desert and south of Egypt to Nubia.[note 12][111] Sahure's cartouche has been found in graffiti in Tumas and on seal impressions from Buhen at the second cataract of the Nile in Lower Nubia.[112][113][114]

Development of the Egyptian Navy

Sahure's reign may have been a time of development for the Egyptian navy. His expeditions to Punt and Byblos demonstrate the existence of a high seas navy and reliefs from his mortuary complex are described by Shelley Wachsmann as the "first definite depictions of seagoing ships in Egypt",[115][116] some of which must have been 100-cubits long (c. 50 m, 170 ft).[27] Because of this, Sahure has been credited by past scholars with establishing the Egyptian navy. It is recognized today that this is an overstatement: fragmentary reliefs from Userkaf's temple depict numerous boats, while a high seas navy must have existed as early as the Third Dynasty.[116] The oldest known sea harbor, Wadi al-Jarf on the Red Sea was operating under Khufu.[117] Finally, there is the distinct possibility that some of the reliefs are copied from earlier examples. Nonetheless, Sahure remains the earliest known ruler to have depicted, and thus possibly made use of, sea power for transporting troops over the Mediterranean sea, to Syria.[118]

The extensive nautical scenes from Sahure's mortuary complex are sufficiently detailed to show that specialized racing boats for the military and perhaps for ceremonial training were built at the time.[119] They also give the earliest depiction of specific rope uses aboard ships, such as that of a hogging-truss.[120] They permit precise estimates regarding shipbuilding, for example indicating that the mid-ship freeboard for seagoing vessels was of 1 m (3.3 ft),[121] and that the masts employed at the time were bipodal, resembling an inverted Y.[122] Further rare depictions include the king standing in the stern of a sailing boat with a highly decorated sail,[123][124] and one of only two[note 13] reliefs from ancient Egypt showing men aboard a ship paddling in a wave pattern, possibly during a race.[126]

Court life

Officials

Several high officials serving Sahure during his lifetime are known from their tombs as well as from the decoration of the mortuary temple of the king. Niankhsekhmet, chief physician of Sahure and first known rhinologist in history,[127] reports that he asked the king that a false door be made for his [Niankhsekhmet's] tomb, to which the king agreed.[128] Sahure had the false door made of fine Tura limestone, carved and painted blue in his audience-hall, and made personal daily inspections of the work.[10][105][129] The king wished a long life to his physician, telling him:

As my nostrils enjoy health, as the gods love me, may you depart into the cemetery at an advanced old age as one revered.[128][130]

A similar though much less detailed anecdote is reported by Khufuankh, who was overseer of the palace and singer of the king.[131] Other officials include Hetepka, who was keeper of the diadem and overseer of the hairdressers of the king,[132] Pehenewkai, priest of the cult of Userkaf during the reigns of Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai, then vizier for the latter;[133] Persen, a mortuary priest in the funerary cult of Sahure's mother Nepherhetepes;[note 14] and Washptah, a priest of Sahure, then vizier of Neferirkare Kakai.[136] The high-official Ptahshepses, probably born during the reign of Menkaure, was high priest of Ptah and royal manicure under Sahure, later promoted to vizier by Nyuserre Ini.[137]

Two viziers of Sahure are known: Sekhemkare, royal prince, son of Khafre and vizier under Userkaf and Sahure;[138] and Werbauba, vizier during Sahure's reign, attested in the mortuary temple of the king.[139][140][141]

Evolution of the high offices

Sahure pursued Userkaf's policy of appointing non-royal people to high offices.[139][143] This is best exemplified by the office of vizier, which was exclusively held by princes of royal blood with the title of "King's son" since the mid-Fourth Dynasty and up until the early Fifth Dynasty.[144] Toward the end of this period princes were progressively excluded from the highest office, an evolution undoubtedly correlated with changes in the nature of kingship.[145] This process, possibly initiated by Menkaure because of dynastic disputes,[146] seems to have been completed by Sahure's time as from then onwards no royal prince was promoted to vizier. Those already in post were allowed to keep their status[147] and so in the early part of Sahure's reign vizier Sekhemkare was a "King's son" while his successor, Werbauba, seems to have been non-royal. In response to this change, the state administration began its expansion as it included more and more non-royal people.[148]

Concurrently with these developments, architectural and artistic innovations relating to tombs of private individuals can be dated to Sahure's reign. These including torus molding and cornices for false doors, first found in Persen's tomb.[149] This feature would subsequently become common and here demonstrates the particularly high esteem in which Persen must have been held by the king.[150] Another innovation is the depiction of small unusual offerings such as that of seven sacred oils on false doors, first found in Niankhsekhmet's tomb.[151] The canonical list of offerings was also developed during or shortly before Sahure's time in the tombs of the royal family, and spread to those of non-royal high-officials[152] – the earliest of whom was Seshemnefer I – under Sahure.[153]

Sun temples

Sekhetre

Sahure built or started to build a temple dedicated to the sun god Ra, the second such temple of the Fifth Dynasty. Yet to be located, it is known to have existed thanks to an inscription on the Palermo stone where it is called Sekhetre (also spelt Sekhet Re), meaning "The Field of Ra"[82] as well as mentions of it in 24 tombs of administration officials.[154] A few limestone blocks bearing reliefs which once adorned the temple have been found embedded in the walls of the mortuary complex of Nyuserre Ini, Sahure's fourth successor.[103] This suggests either that these blocks were leftovers from the construction of the temple, or as Wener Kaiser has posited,[155] that Nyuserre dismantled Sahure's temple,[156] using it as a quarry for construction materials because it was largely unfinished.[52][103] Indeed, the rather meager evidence for the Sekhetre leads Miroslav Verner to propose that it never fully functioned as a sun temple.[156]

New analyses of the verso of the Palermo stone performed in 2018 by the Czech Institute of Archeology enabled the reading of further inscriptions mentioning precisely the architecture of the temple as well as lists of donations it received, establishing firmly that it was a distinct entity from the earlier sun temple of Userkaf, the Nekhenre but leaving its ultimate fate uncertain.[157] Further precision as to the architecture of the temple may be inferred from the absence[156] of the obelisk determinative in some hieroglyphic variants of the name Sekhetre and its presence in others. For Anthony Spalinger this possibly indicates that Sahure's sun temple was effectively built and acquired such an obelisk at some point after its construction, perhaps after Sahure's reign.[158]

Nekhenre

Userkaf was the first king to build a sun temple in Abusir. Known to the ancient Egyptians as the Nekhenre, or "Fortress of Re", it was unfinished at his death. Construction works continued in at least four building phases, the first of which may have taken place under Sahure,[156] and then under his successors Neferirkare Kakai and Nyuserre Ini.[159][160]

Pyramid complex

Sahure built a pyramid complex for his tomb and funerary cult, named Khaba Sahura,[161] which is variously translated as "The Rising of the Ba Spirit of Sahure",[162][163] "The Ba of Sahure appears",[6] "Sahure's pyramid where the royal soul rises in splendor",[164] or "In glory comes forth the soul of Sahure".[165] The builders and artisans who worked on Sahure's mortuary complex lived in an enclosed pyramid town located next to the causeway leading up to Sahure's pyramid and mortuary temple. The town later flourished under Nyuserre and seems to have still been in the existence during the First Intermediate Period.[166]

In terms of the size, volume, and the cheap construction techniques employed, Sahure's pyramid exemplifies the decline of pyramid building.[note 15] At the same time, the quality and variety of the stones employed in other parts of the complex increased,[168] and the mortuary temple is considered to be the most sophisticated one built up to that time.[12] With its many architectural innovations, such as the use of palmiform columns, the overall layout of Sahure's complex would serve as the template for all mortuary complexes constructed from Sahure's reign until the end of the Sixth Dynasty, some 300 years later.[27][169] The highly varied colored reliefs decorating the walls of the entire funerary complex display a quality of workmanship and a richness of conception that reach their highest level of the entire Old Kingdom period.[168]

Location

Sahure chose to construct his pyramid complex in Abusir, thereby abandoning both Saqqara and Giza, which had been the royal necropolises up to that time. A possible motivation for Sahure's decision was the presence of the sun temple of Userkaf,[170] something which supports the hypothesis that Sahure was Userkaf's son.[171] Following Sahure's choice, Abusir became the main necropolis of the early Fifth Dynasty, as pharaohs Neferirkare Kakai, Neferefre, Nyuserre Ini and possibly Shepseskare built their pyramids there. In their wake, many smaller tombs belonging to members of the royal family were built in Abusir, with the notable exceptions of those of the highest-ranking members, many of whom chose to be buried in Giza or Saqqarah.[172]

Mortuary temple

Sahure's mortuary temple was extensively decorated with an estimated 10,000 m2 (110,000 sq ft) of fine reliefs.[173] This extensive decoration seems to have been completed within Sahure's lifetime.[174] The walls of the entire 235 m (771 ft)-long causeway were also covered with polychrome bas-reliefs.[162][175] Miroslav Bárta describes the reliefs as "the largest collection known from the third millennium BCE".[176]

Many surviving fragments of the reliefs which decorated the walls of the mortuary complex are of very high quality and much more elaborate than those from preceding mortuary temples.[9][177] Several of the depictions are unique in Egyptian art. These include a relief showing Sahure tending a myrrh tree (Commiphora myrrha) in his palace in front of his family;[178][179] a relief depicting Syrian brown bears and another showing the bringing of the pyramidion to the main pyramid and the ceremonies following the completion of the complex.[180] The high craftmanship of the reliefs is here manifested by the finely rounded edges of all figures, so that they simultaneously blend in with the background and stand out clearly.[181] Reliefs are sufficiently detailed to permit the identification of the animals shown, such as hedgehogs and jerboas,[182] and even show personified plants such as corn represented as a man with corn-ears instead of hair.[90]

The many reliefs of the mortuary, causeway and valley temples also depict, among other things, Sahure hunting wild bulls and hippopotamuses,[183] Sahure being suckled by Nekhbet,[184] the earliest depictions of a king fishing and fowling,[185][186] a counting of foreigners by or in front of the goddess Seshat, which Egyptologist Mark Lehner believes was "meant to ward off any evil or disorder",[162] the god Sopdu "Lord of the Foreign Countries" leading bound Asiatic captives,[72] and the return of an Egyptian fleet from Asia, perhaps Byblos. Some of the low relief-cuttings in red granite are still in place at the site.[28][187] Among the seminal innovations of Sahure's temple are the earliest relief depictions of figures in adoration, either standing or squatting with both arms raised, their hands open and their palms facing down.[188]

The mortuary temple featured the first palmiform columns of any Egyptian temple,[27] massive granite architraves inscribed with Sahure's titulary overlaid with copper, lion-headed waterspouts, black basalt flooring[189] and granite dados.[27]

Pyramid

The pyramid of Sahure reached 47 m (154 ft) at the time of its construction,[162] much smaller than the pyramids of the preceding Fourth Dynasty. Its inner core is made of roughly hewn stones organized in steps and held together in many sections with a thick mortar of mud. This construction technique, much cheaper and faster to execute than the stone-based techniques hitherto employed, fared much worse over time. Owing to this, Sahure's pyramid is now largely ruined and amounts to little more than a pile of rubble showing the crude filling of debris and mortar constituting the core, which became exposed after the casing stones were stolen in antiquity.[27]

While the core was under construction, a corridor was left open leading into the shaft where the grave chamber was built separately and later covered by leftover stone blocks and debris. This construction strategy is clearly visible in later unfinished pyramids, in particular the Pyramid of Neferefre.[27] This technique also reflects the older style from the Third Dynasty seemingly coming back into fashion after being temporarily abandoned by the builders of the five great pyramids at Dahshur and Giza during the Fourth Dynasty.[27]

The entrance at the north side is a short descending corridor lined with red granite followed by a passageway ending at the burial chamber with its gabled roof comprising large limestone beams of several tons each.[190] Today all of these beams are fractured, which weakens the pyramid structure. Fragments of a basalt sarcophagus, likely Sahure's, were found here in the burial chamber when it was first entered by John Shae Perring in the mid 19th century.[27]

The mortuary complex immediately around the pyramid also includes a second smaller cult pyramid which must have stood nearly 12 m (39 ft) high, originally built for the Ka of the king.[27]

Legacy

Artistic and architectural legacy

The painted reliefs covering the walls of Sahure's mortuary temple were recognized as an artistic achievement of the highest degree by the Ancient Egyptians. A New Kingdom inscription found in Abusir for example poetically compares the temple to the heaven lit by full moon.

Subsequent generations of artists and craftsmen tried to emulate Sahure's reliefs, using them as templates for the tombs of later kings and queens of the Old Kingdom period.[192] The layout of Sahure's high temple was also novel and it became the standard template for all subsequent pyramid complexes of the Old Kingdom. Some of its architectural elements, such as its palmiform columns, became hallmarks of Egyptian architecture.[note 16][27][194]

This trend continued to hold in later times. For example, in the Middle Kingdom, Senusret I had reliefs for his temple directly copied from those of Sahure. He also chose to follow the innovative layout of Sahure's complex once again. At the time, Senusret I's decision was in stark contrast with the burial customs of the 11th Dynasty pharaohs, who were buried in saff tombs. These consisted of an open courtyard fronting a row of entrances into subterranean corridors and chambers dug in the hillsides of El-Tarif and Deir el-Bahari, near Thebes.[note 17][195]

Old Kingdom

Sahure was the object of a funerary cult from the time of his death and which continued until the end of the Old Kingdom, some 300 years later. At least 22 agricultural estates were established to produce the goods necessary for providing the offerings to be made for this cult.[139] Decorated reliefs from the upper part of the causeway represent the procession of over 150 personified funerary domains created by and for Sahure, demonstrating the existence of a sophisticated economic system associated with the king's funerary cult.[196] The enormous quantities of offerings pouring into the mortuary and sun temples of Sahure benefitted other cults as well, such as that of Hathor, which had priests officiating on the temple premises.[197]

Several priests serving the mortuary cult or in Sahure's sun temple during the later Fifth and Sixth Dynasties are known thanks to inscriptions and artifacts from their tombs in Saqqara and Abusir.[198] These include Tjy, overseer of the sun temples of Sahure, Neferirkare, Neferefre and Nyuserre;[199] Neferkai priest of Sahure's funerary cult;[200] Khabauptah priest of Sahure, Neferirkare, Neferefre, and Niuserre,[201][202] Atjema, priest of the sun temple of Sahure during the Sixth Dynasty;[203] Khuyemsnewy, who served as priest of the mortuary cult of Sahure during the reigns of Neferirkare and Nyuserre;[note 18] Nikare, priest of the cult of Sahure and overseer of the scribes of the granary during the Fifth Dynasty.[205] Further priests are known, such as Senewankh, serving in the cults of Userkaf and Sahure and buried in a mastaba in Saqqara;[206] Sedaug, a priest of the cult of Sahure, priest of Ra in the sun-temple of Userkaf and holder of the title of royal acquaintance;[207] Tepemankh, priest of the cults of kings of the Fourth to early Fifth Dynasty including Userkaf and Sahure, buried in a mastaba at Abusir.[208][209][210]

Middle Kingdom

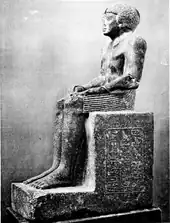

No priest serving in the funerary cult of Sahure is known from the Middle Kingdom period. Evidence from this period rather come from works undertaken in the Karnak temple by 12th Dynasty pharaoh Senusret I (fl. 20th century BC), who dedicated statues of Old Kingdom kings[212] including one of Sahure.[note 19][214] The statue and the accompanying group of portraits of deceased kings indicates the existence of a generic cult of royal ancestor figures, a "limited version of the cult of the divine" as Jaromir Málek writes.[215] The statue of Sahure, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (catalog number CG 42004), is made of black granite and is 50 cm (20 in) tall. Sahure is shown enthroned, wearing a pleated skirt and a round curly wig. Both sides of the throne bear inscriptions identifying the work as a portrait of Sahure made on the orders of Senusret I.[216]

Sahure's legacy had endured sufficiently by the Middle Kingdom period that he is mentioned in a story of the Westcar Papyrus, probably written during the 12th Dynasty although the earliest extent copy dates to the Seventeenth Dynasty.[217] The papyrus tells the mythical story of the origins of the Fifth Dynasty, presenting kings Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai as three brothers, sons of Ra and a woman named Rededjet destined to supplant Khufu's line.[34]

New Kingdom: emergence of Sekhmet of Sahure

As a deceased king, Sahure continued to receive religious offerings during the New Kingdom as part of the standard cult of the royal ancestors. For example, Sahure is present on the Karnak king list, a list of kings inscribed on the walls of the Akhmenu, the Karnak temple of Thutmose III. Unlike other ancient Egyptian king lists, the kings there are not listed in chronological order. Rather, the purpose of the list was purely religious, its aim being to name the deceased kings to be honored in the Karnak temple.[214]

In the second part of the Eighteenth Dynasty and during the Nineteenth Dynasty numerous visitors left inscriptions, stelae and statues in the temple.[218][219] These activities were related to a cult then taking place in the mortuary temple of Sahure since the time of Thutmose III. This cult was devoted to the deified king in a form associated with the goddess Sekhmet[220][221][222] named "Sekhmet of Sahure".[223] For example, the scribe Ptahemuia and fellow scribes visited Sahure's temple in the 30th year of Ramses II's reign (c. 1249 BC) to ask Sekhmet to grant them a long life of 110 years.[224] The reason for the appearance of this cult during the New Kingdom is unknown.[225] In any case, the cult of Sekhmet of Sahure was not a purely local phenomenon as traces of it were found in the Upper Egyptian village of Deir el-Medina, where it was celebrated during two festivals taking place every year, on the 16th day of the first month of Peret and on the 11th day of the fourth month of that season.[226]

During the same period, prince Khaemwaset, a son of Ramses II, undertook works throughout Egypt on pyramids and temples which had fallen into ruin, possibly to appropriate stones for his father's construction projects while ensuring a minimal restoration for cultic purposes.[227] Inscriptions on the stone cladding of the pyramid of Sahure show that it was the object of such works at this time.[198][228] This renewed attention had negative consequences as the first wave of dismantlement of the Abusir monuments, particularly for the acquisition of valuable Tura limestone, arrived with it. Sahure's mortuary temple may have been spared at this time due to the presence of the cult of Sekhmet.[229] The cult's influence likely waned after the end of Ramses II's reign, becoming a site of local worship only.[230]

Third intermediate, late and Ptolemaic periods

During the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (744–656 BC) at the end of the Third Intermediate Period, some of Sahure's temple reliefs were copied by Taharqa,[231] including images of the king crushing his enemies as a sphinx.[232] Shortly after, under the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664–525 BC) of the Late Period, a statue of Sahure was among a group of statues of Old Kingdom kings hidden in a cachette of the Karnak temple, testifying to some form of cultic interest up to that time.[233] In parallel, a new period of dismantlement of the pyramids of Abusir took place, yet Sahure's was once again spared. This might be because of the cult of Sekhmet of Sahure[223] the temple hosted well into the Ptolemaic period (332–30 BC), albeit with a very reduced influence.[234] Several graffiti dating from the reigns of Amasis II (570–526 BC), Darius II (423–404 BC) and up until the Ptolemaic period attest to continued cultic activities on the site.[198][235][236] For example, a certain Horib was "Priest of Sekhmet of the temple of Sekhmet of Sahure" under the Ptolemaic dynasty.[237]

The dismantlement of Sahure's pyramid started in earnest in the Roman period, as shown by the abundant production of mill-stones, presence of lime production facilities and worker shelters in the vicinity.[238]

Notes

- Proposed dates for the reign of Sahure: 2517–2505 BC,[4] 2506–2492 BC,[5][6] 2496–2483 BC,[7][8] 2491–2477 BC,[9] 2487–2475 BC,[10][11][12][13][14][15][16] 2471–2458 BC,[17] 2458–2446 BC,[1][18][19] 2446–2433BC,[8] 2428–2417 BC,[20] 2428–2416 BC.[21]

- Ancient Egyptian Mwt-Nswt.[31]

- In a version of this theory, Khentkaus possibly remarried Userkaf after the death of her first husband[33] and became the mother of Sahure and his successor on the throne, Neferirkare Kakai.[10] This theory is based on the fact that Khentkaus is known to have borne the title of mwt nswt bity nswt bity, which could be translated as "mother of two kings". A story from the Westcar Papyrus tells of a magician foretelling to Khufu that the future demise of his lineage will come from three brothers, born of the god Ra and a woman named Rededjet, who will reign successively as the first three kings of the Fifth Dynasty.[34] Some Egyptologists have therefore proposed that Khentkaus was the mother of Sahure and the historical figure on which Rededjet is based. Following the discoveries of Verner and El-Awady in Abusir, this theory has been abandoned[29] and the real role of Khentkaus remains difficult to ascertain. This is in part because the translation of her title is problematic and because the details of the transition from the Fourth to the Fifth Dynasty are not yet clear. In particular, an ephemeral pharaoh Djedefptah may have ruled between Shepseskaf and Userkaf.[33]

- The first pharaoh to have a throne name, called the prenomen, different from his birth name, called the nomen

- During the Old Kingdom period, the Egyptians did not record time as we do today. Rather, they counted years since the beginning of the reign of the current king. Furthermore these years were referred to by the number of cattle counts which had taken place since the start of the reign. The cattle count was an important event aimed at evaluating the amount of taxes to be levied on the population. This involved counting cattle, oxen and small livestock.[51] During the first half of the Fifth Dynasty, this count might have been biennial[52] although it may not always have happened at regular intervals.[53] Following these principles, the Palermo stone actually talks of the years after the first, second and either sixth or seventh[54] cattle counts of Sahure's reign. If the count was indeed biennial, which is uncertain, this would correspond to Sahure's second, third and fourteenth years.

- In the context of Egyptology, the term "Asiatics" is used to refer to people from the Levant, including Canaan, modern-day Lebanon and the southern coast of modern-day Turkey.

- It is possible that the Egyptians wielded sufficient influence over Byblos at the time to have the temple built to satisfy their cultic needs, as they could have sought the protection of Baalat as a form of Hathor. As this remains conjectural, alternative explanations have been brought forth to explain the presence of Egyptian artifacts and Egyptian influence on the temple layout. The architects of the temple may have been Egyptians working for the Byblite king while the alabaster bowl found in the temple could come from Egyptian payments to the Byblite king for wood,[65] or it may have been donated by pious individuals.[66] While the Egyptian influence over Byblos cannot be denied, there is far from enough evidence to conclude that Byblos functioned as an Egyptian colony at the time of Sahure.[66]

- Finally, a piece of thin gold stamped to a wooden throne and bearing Sahure's cartouches has been purportedly found during illegal excavations in Turkey among a wider assemblage known as the "Dorak Treasure".[9][69][6] The existence of the treasure is now widely doubted.[70]

- The expedition to the copper mine of Wadi Kharit left an inscription reading: "Horus Lord-of-Risings, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Sahure, granted life eternally. Thot lord-of-terror who smashes Asia".[78]

- The relief say that the following was taken as bounty: over 123,440 cattle, more than 223,200 donkeys, 232,413 goats and 243,688 sheep.[83] In another scene, 212,400 donkeys are said to have been taken.[84][85] Even if these numbers are overestimates, they show that Tjemehu was seen by the Egyptians as a rich land,[83] and that economic considerations motivated Egyptians attempts at controlling the neighboring lands.[60]

- The Iunti and Montiu were Nubian and Asiatic nomads, respectively.[91]

- This is one of only three known statues of Sahure, the other two being that of Sahure with a nome god heading this article, and that dedicated by Senusret I shown at the end this article.[111]

- The only other similar relief is found in Userkaf's temple.[125]

- His mastaba tomb is located close to Nepherhetepes's pyramid in Saqqara.[29][134][135]

- For example, Sahure's main pyramid had a volume of 98,000 m3 (3,500,000 cu ft) versus Khufu's 2,595,000 m3 (91,600,000 cu ft).[167]

- The standard work on Sahure's pyramid complex is Borchardt's excavation report, available online in its entirety.[193]

- This change may have been spurred by the return of the Egyptian capital to Middle Egypt, in Itjtawy, close to Memphis and the attraction of then already ancient pyramids of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties.[195]

- Khuyemsnewy was also priest of Ra and Hathor in Neferirkare's sun temple, priest of Neferirkare, priest in Nyuserre Ini's and Neferirkare Kakai's pyramid complexes and Overseer of the Two Granaries.[204]

- Another statue from this group is that of Intef the Elder.[213]

References

- MET 2015.

- Allen et al. 1999, pp. 329–330.

- Online archive 2014.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 144.

- Verner 2001b, p. 588.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 598.

- Walters Art Museum website 2015.

- von Beckerath 1997, p. 188.

- Clayton 1994, pp. 60–63.

- Rice 1999, p. 173.

- Málek 2000a, pp. 83–85.

- Baker 2008, pp. 343–345.

- Sowada 2009, p. 3.

- Mark 2013, p. 270.

- Huyge 2017, p. 41.

- Bard & Fattovich 2011, p. 116.

- von Beckerath 1999, p. 283.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. xx.

- Phillips 1997, p. 426.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- Leprohon 2013, p. 38.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 337.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 62–69.

- El Awady 2006a, pp. 214–216.

- Borchardt 1910, p. Plate (Blatt) 32, 33 & 34.

- Lehner 2008, pp. 142–144.

- Brinkmann 2010a, Book abstract, English translation available online and on the Internet archive.

- El Awady 2006a, pp. 192–198.

- Labrousse & Lauer 2000.

- Baud 1999b, p. 494.

- Clayton 1994, p. 46.

- Hayes 1978, pp. 66–68 & p. 71.

- Lichteim 2000, pp. 215–220.

- Baud 1999b, pp. 547–548 & 550.

- Borchardt 1910, Pl. 32, 33 & 34.

- Verner 2002, p. 268.

- Baud 1999b, pp. 509–510.

- El Awady 2006a, pp. 208–213.

- El Awady 2006a, pp. 213–214.

- El Awady 2006a, pp. 198–203.

- Callender 2011, p. 133 & 141.

- Baud 1999b, p. 535.

- Baud 1999b, p. 521.

- Baud 1999b, p. 487.

- Mac Farlane 1991, p. 80.

- Baud 1999a, p. 297.

- von Beckerath 1999, pp. 56–57, king number 2.

- Waddell 1971, p. 51.

- Daressy 1912, p. 205.

- Katary 2001, p. 352.

- Verner 2001a, p. 391.

- Spalinger 1994, p. 297.

- Wilkinson 2000, p. 168.

- Wilkinson 2000, p. 259.

- Breasted 1906, p. 70.

- Gardiner, Peet & Černý 1955, p. 15.

- Sethe 1903, p. 32.

- Hayes 1978, pp. 66–67.

- Bresciani 1997, p. 228.

- Redford 1986, p. 137.

- Bresciani 1997, p. 229.

- Sowada 2009, p. 160 and Fig. 39.

- Smith 1971, p. 233.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 150.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 151.

- Saghieh 1983, p. 121.

- Espinel 2002, pp. 105–106.

- Smith 1965, p. 110.

- Mazur 2005.

- Mumford 2006, p. 54.

- Mumford 2006, p. 55.

- Sowada 2009, p. 198.

- Hawass 2003, pp. 260–263.

- Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- Wicker 1998, p. 155.

- Strudwick 2005, p. 135, text number 57.

- Giveon 1977, p. 61.

- Giveon 1977, pp. 61–63.

- Giveon 1978, p. 76.

- Mumford 1999, pp. 875–876.

- Breasted 1906, pp. 108–110.

- García 2015, p. 78.

- Borchardt 1913, pl. 1–5 & 19.

- Sethe 1903, pp. 167–169.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 156.

- Baines 2011, pp. 65–66.

- Kuiper 2010, p. 48.

- García 2015, p. 79 & 99.

- Eisler & Hildburgh 1950, p. 130.

- Bresciani 1997, p. 268.

- Goedicke 1988, p. 119.

- Sethe 1903, 243,3.

- Dunn Friedman & Friedman 1995, p. 29 & Fig. 18b p. 31.

- Strudwick 2005, pp. 71–72.

- Rowland 2011, p. 29.

- Routledge 2007, p. 216.

- Routledge 2007, p. 220.

- Routledge 2007, p. 194.

- Tooley 1996, p. 174, footnote 22.

- Baud 1999a, p. 336.

- Labrousse 1997, p. 265.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 110.

- Verner 2012, pp. 16–19.

- Wilson 1947, pp. 241–242.

- Verner 2003, p. 150.

- Bloxam & Heldal 2007, p. 312.

- Smith 1971, p. 167.

- Green 1909, p. 321 & pl. LIV.

- Bradbury 1988, p. 151.

- Huyge 2017, pp. 41–43.

- Petrie Museum, online catalog, seal UC 21997 2015.

- Petrie Museum, online catalog, seal UC 11769 2015.

- List of attestations of Sahure 2000.

- Wachsmann 1998, p. 12.

- Faulkner 1941, p. 4.

- Tallet 2012.

- Faulkner 1941, p. 3.

- Mark 2013, p. 285.

- Veldmeijer et al. 2008, p. 33.

- Wicker 1998, p. 161.

- Faulkner 1941, p. 6.

- El Awady 2009, pl. 1 & Fig. 2.

- Mark 2013, p. 272.

- Mark 2013, p. 280.

- Mark 2013, pp. 270, 280–281.

- Pahor & Farid 2003, p. 846.

- Breasted 1906, pp. 108–109.

- Ghaliounghui 1983, p. 69.

- Sethe 1903, p. 38.

- Wilson 1947, p. 242.

- Emery 1965, p. 4.

- Sethe 1903, p. 48.

- Breasted 1906, pp. 109–110.

- Lauer & Flandrin 1992, p. 122.

- Sethe 1903, p. 40.

- Online catalog of the British Museum.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 136.

- Schneider 2002, pp. 243–244.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 80.

- List of viziers 2000.

- Borchardt 1913, pl. 17.

- Dorman 2014.

- Schmitz 1976, p. 84.

- Schmitz 1976, p. 166.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 339.

- Strudwick 1985, pp. 312–313.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 338.

- Strudwick 1985, pp. 10, 15 & footnote 3 p. 10.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 15.

- Strudwick 1985, pp. 26–27.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 41.

- Strudwick 1985, pp. 39–40.

- Spalinger 1994, p. 295.

- Kaiser 1956, p. 112.

- Verner 2001a, p. 390.

- Czech Institute of Egyptology website 2018.

- Spalinger 1994, p. 295–296.

- Lehner 2008, p. 150.

- Verner 2001a, pp. 387–389.

- Brugsch 2015, p. 88.

- Lehner 2008, p. 143.

- Hellum 2007, p. 100.

- Bennett 1966, p. 175.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 71.

- Verner 2012, p. 409.

- Mumford 2006, p. 49.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 68.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 69.

- Krecji 2003, p. 281.

- Verner 2001a, p. 389.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 53.

- El-Shahawy & Atiya 2005, p. 33.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 64.

- Mark 2013, p. 271.

- Bárta 2017, p. 6.

- Borchardt 1910, p. Plate (Blatt) 9.

- El Awady 2006b, p. 37.

- El Awady 2009, pls. 5–6.

- Strudwick 2005, p. 86.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 333.

- Evans 2011, p. 110.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 276.

- Budin 2014, pp. 45–46.

- El Awady 2009, pl. 13.

- Hsu 2012, p. 281.

- Brinkmann 2010b, Video presentation of the exhibition.

- El-Khadragy 2001, p. 187, see footnote 2.

- Hoffmeier 1993, pp. 118–119.

- Edwards 1972, pp. 175–176, 180–181 & 275.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 60.

- Borchardt 1910.

- Hayes 1978, p. 68.

- Lansing 1926, p. 34.

- Khaled 2013.

- Gillam 1995, p. 216.

- Wildung 2010, pp. 275–276.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 159.

- Brooklyn Museum 2019.

- Mariette 1885, p. 295.

- Callender 2011, p. 141, footnote 78.

- Allen et al. 1999, pp. 456–457.

- Hayes 1978, p. 106.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 370.

- Sethe 1903, p. 36.

- Junker 1950, pp. 107–118.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 404.

- Strudwick 2005, p. 248, text number 173.

- Sethe 1903, p. 33.

- Legrain 1906, CG 42004.

- Grimal 1992, p. 180.

- Legrain 1906, pp. 4–5 & pl. III.

- Wildung 1969, pp. 60–63.

- Málek 2000b, p. 257.

- Legrain 1906, pp. 3–4.

- Burkard, Thissen & Quack 2003, p. 178.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 101.

- Peden 2001, pp. 59–60, 95–96.

- Morales 2006, p. 313.

- Horváth 2003, pp. 63–70.

- Verner 2001a, p. 393.

- Gaber 2003, p. 18.

- Grinsell 1947, pp. 349–350.

- Gaber 2003, p. 28.

- Gaber 2003, pp. 19 & 28.

- Málek 1992, pp. 57–76.

- Wildung 1969, p. 170.

- Bareš 2000, p. 9.

- Bareš 2000, p. 11.

- Bareš 2000, p. 12.

- Kahl 2000, pp. 225–226.

- Morales 2006, pp. 320–321.

- Bareš 2000, pp. 13–14.

- Wildung 1969, p. 198.

- Peden 2001, pp. 278–279.

- Gaber 2003, p. 19.

- Bareš 2000, pp. 14–15.

Bibliography

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; Arnold, Arnold; Arnold, Dorothea; Cherpion, Nadine; David, Élisabeth; Grimal, Nicolas; Grzymski, Krzysztof; Hawass, Zahi; Hill, Marsha; Jánosi, Peter; Labée-Toutée, Sophie; Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Phillippe; Leclant, Jean; Der Manuelian, Peter; Millet, N. B.; Oppenheim, Adela; Craig Patch, Diana; Pischikova, Elena; Rigault, Patricia; Roehrig, Catharine H.; Wildung, Dietrich; Ziegler, Christiane (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 41431623.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Baines, John (2011). "Ancient Egypt". In Feldherr, Andrew; Hardy, Grant (eds.). The Oxford History of Historical Writing, Volume 1: Beginnings to AD 600. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–75. ISBN 978-0-19-103678-1.

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. London: Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- Bard, Kathryn A.; Fattovich, Rodolfo (2011). "The Middle Kingdom Red Sea Harbor at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 47: 105–129. JSTOR 24555387.

- Bareš, Ladislav (2000). "The destruction of the monuments at the necropolis of Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 1–16. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. San Diego: The University of California. 1 (1).

- Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- Bennett, John (1966). "Pyramid Names". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. Sage Publications, Ltd. 52: 174–176. doi:10.1177/030751336605200122. JSTOR 3855832. S2CID 221765432.

- Bloxam, Elizabeth; Heldal, Tom (2007). "The Industrial Landscape of the Northern Faiyum Desert as a World Heritage Site: Modelling the 'Outstanding Universal Value' of Third Millennium BC Stone Quarrying in Egypt". World Archaeology. The Archaeology of World Heritage. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 39 (3): 305–323. doi:10.1080/00438240701464905. JSTOR 40026202. S2CID 53134735.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1910). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re (Band 1): Der Bau: Blatt 1–15 (in German). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. ISBN 978-3-535-00577-1.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1913). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re (Band 2) (in German). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. OCLC 936475141.

- Bradbury, Louise (1988). "Reflections on Traveling to "God's Land" and Punt in the Middle Kingdom". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 25: 127–156. doi:10.2307/40000875. JSTOR 40000875.

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient records of Egypt historical documents from earliest times to the Persian conquest, collected edited and translated with commentary, vol. I The First to the Seventeenth Dynasties. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 491147601.

- Bresciani, Edda (1997). "Foreigners". In Donadoni, Sergio (ed.). The Egyptians. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 221–255. ISBN 0-226-15556-0.

- Brinkmann, Vinzenz, ed. (2010a). Sahure: Tod und Leben eines grossen Pharao (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Liebieghaus. ISBN 978-3-7774-2861-1.

- Brinkmann, Vinzenz. Sahure. Tod und Leben eines großen Pharao. Bis 28.11.2010 im Liebieghaus (video) (in German). Liebieghaus.

- Brugsch, Heinrich Karl (2015) [1879]. Smith, Philip (ed.). A History of Egypt under the Pharaohs, Derived Entirely from the Monuments : To which is added a memoir on the exodus of the Israelites and the Egyptian Monuments. Vol. 1. Translated by Seymour, Henry Danby. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-08472-7.

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2014). Images of woman and child from the Bronze Age: reconsidering fertility, maternity, and gender in the ancient world. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10-766032-8.

- Burkard, Günter; Thissen, Heinz Josef; Quack, Joachim Friedrich (2003). Einführung in die altägyptische Literaturgeschichte. Band 1: Altes und Mittleres Reich. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 1, 3, 6. Münster: LIT. ISBN 978-3-82-580987-4.

- Callender, Vivienne Gae (2011). "Curious names of some Old Kingdom royal women". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 97: 127–142. doi:10.1177/030751331109700109. S2CID 192564857.

- "Clay impression of a seal of Sahure UC 11769". Online catalog of the Petrie Museum. 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Czech Institute of Egyptology website (1 October 2018). "New research and insights into the Palermo Stone". cegu.ff.cuni.cz. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Dates of Sahure's reign". Website of the Walters Art Museum. 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Daressy, Georges (1912). "La Pierre de Palerme et la chronologie de l'Ancien Empire". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). Cairo. 12: 161–214. ISSN 0255-0962. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Dorman, Peter (2014). "The 5th dynasty (c. 2465 – c. 2325 BC)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Dunn Friedman, Florence; Friedman, Florence (1995). "The Underground Relief Panels of King Djoser at the Step Pyramid Complex". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 32: 1–42. doi:10.2307/40000828. JSTOR 40000828.

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1972). The Pyramids of Egypt. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-67-058361-4.

- Eisler, Robert; Hildburgh, W. L. (1950). "The Passion of the Flax". Folklore. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 61 (3): 114–133. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1950.9717999. JSTOR 1257742.

- El Awady, Tarek (2006). "The royal family of Sahure. New evidence" (PDF). In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 31–45. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2011.

- El Awady, Tarek (2006). "King Sahure with the Precious Trees from Punt in a Unique Scene!". In Bárta, Miroslav (ed.). The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology, Proceedings of the conference held in Prague, May 31 – June 4, 2004. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. pp. 37–44. ISBN 978-8-02-001465-8.

- El Awady, Tarek (2009). Sahure – The Pyramid Causeway: History and Decoration Program in the Old Kingdom. Abusir monographs. Vol. XVI. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology. ISBN 978-8073082550.

- El-Khadragy, Mahmoud (2001). "The Adoration Gesture in Private Tombs up to the Early Middle Kingdom". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 29: 187–201. JSTOR 25152842.

- El-Shahawy, Abeer; Atiya, Farid S. (2005). The Egyptian Museum in Cairo. A walk through the alleys of ancient Egypt. Cairo: Farid Atiya Press. ISBN 978-9-77-171983-0.

- Emery, W. B. (1965). "Preliminary Report on the Excavations at North Saqqâra 1964-5". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. Sage Publications, Ltd. 51: 3–8. doi:10.2307/3855614. JSTOR 3855614.

- Espinel, Andrés Diego (2002). "The Role of the Temple of Ba'alat Gebal as Intermediary between Egypt and Byblos during the Old Kingdom". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 30: 103–119. JSTOR 25152861.

- Evans, Linda (2011). "The Shedshed of Wepwawet: an artistic and behavioural interpretation". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 97: 103–115. doi:10.1177/030751331109700107. JSTOR 23269890. S2CID 190475162.

- "False Door of Neferk(ai)". Brooklyn Museum. 2019.

- Faulkner, R. O. (1941). "Egyptian Seagoing Ships". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 26: 3–9. doi:10.1177/030751334002600102. JSTOR 3854516. S2CID 192298351.

- Gaber, Amr (2003). "Aspects of the deification of some Old Kingdom kings". In Eyma, Aayko K.; Bennett, C. J. (eds.). A delta-man in Yebu. Occasional volume of the Egyptologists' electronic forum. Vol. 1. Boca Raton: Universal Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58-112564-1.

- García, Juan Carlos Moreno (2015). "Ḥwt jḥ(w)t, The administration of the Western Delta and the 'Libyan question' in the third millennium BC". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 101: 69–105. doi:10.1177/030751331510100104. JSTOR 26379038. S2CID 193622997.

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson; Peet, Thomas Eric; Černý, Jaroslav (1955). The Inscriptions of Sinai, edited and completed by Jaroslav Cerný. London: Egypt Exploration Society. OCLC 559072028.

- Ghaliounghui, Paul (1983). The Physicians of Pharaonic Egypt. Cairo: A.R.E.: Al-Ahram Center for Scientific Translations. ISBN 978-3-8053-0600-3.

- Gillam, Robyn A. (1995). "Priestesses of Hathor: Their Function, Decline and Disappearance". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 32: 211–237. doi:10.2307/40000840. JSTOR 40000840.

- Giveon, Raphael (1977). "Inscriptions of Sahurēʿ and Sesostris I from Wadi Khariǧ (Sinai)". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 226 (226): 61–63. doi:10.2307/1356577. JSTOR 1356577. S2CID 163793800.

- Giveon, Raphael (1978). "Corrected Drawings of the Sahure and Sesostris I Inscriptions from the Wadi Kharig". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 232: 76. doi:10.2307/1356703. JSTOR 1356703. S2CID 163409094.

- Goedicke, Hans (1988). "The death of Pepi II Neferkare". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. Helmut Buske Verlag GmbH. 15: 111–121. ISSN 0340-2215.

- Green, Frederick Wastie (1909). "Notes on some inscriptions in the Etbai district". Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. Vol. 31. London: Society of Biblical Archaeology. pp. 247–254 & 319–323. OCLC 221790304.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Grinsell, L. V. (1947). "The Folklore of Ancient Egyptian Monuments". Folklore. 58 (4): 345–360. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1947.9717870. JSTOR 1257192.

- Hawass, Zahi (2003). Accomazzo, Laura; Manferto de Fabianis, Valeria (eds.). The Treasure of the Pyramids. Vercelli Italy: White Star publishers. ISBN 978-88-8095-233-6.

- Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 7427345.

- Hellum, Jennifer (2007). The Pyramids. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32580-9.

- Hoffmeier, James K. (1993). "The Use of Basalt in Floors of Old Kingdom Pyramid Temples". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 30: 117–123. doi:10.2307/40000231. JSTOR 40000231.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Horváth, Z. (2003). Popielska-Grzybowska, J. (ed.). "Sahurâ and his Cult-Complex in the Light of Tradition". Proceedings of the Second Central European Conference of Young Egyptologists. Egypt 2001: Perspectives of Research, Warsaw 5–7 March 2001. Warsaw: 63–70. ISBN 978-8-38-749676-0.

- Hsu, Shih-Weih (2012). "The development of ancient Egyptian royal inscriptions". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 98: 269–283. doi:10.1177/030751331209800115. JSTOR 24645014. S2CID 190032178.

- Huyge, Dirk (2017). "King Sahure in Elkab". Egyptian Archaeology. Egyptian Exploration Society. 50. ISSN 0962-2837.

- Junker, Hermann (1950). Giza. 9, Das Mittelfeld des Westfriedhofs (PDF). Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, 73.2 (in German). Wien: Rudolf M. Rohrer. OCLC 886197144.

- Kaiser, Werner (1956). "Zu den Sonnenheiligtümern der 5. Dynastie". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. 14: 104–116. OCLC 917064527.

- Kahl, Jochem (2000). "Die Rolle von Saqqara und Abusir bei der Überlieferun altägyptischer Jenseitsbücher". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000 (in German). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 215–228. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Katary, Sally (2001). "Taxation". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–356. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Khaled, Mohamed Ismail (2013). "The Economic Aspects of the Old Kingdom Royal Funerary Domains". Études et Travaux. XXVI: 366–372.

- "King Sahure and a Nome God". Online catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Krecji, Jaromir (2003). "Appearance of the Abusir Pyramid Necropolis during the Old Kingdom". In Hawass, Zahi; Pinch Brock, Lyla (eds.). Egyptology at the dawn of the Twenty-first Century: proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, Cairo, 2000. Cairo, New York: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9-77-424674-6.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). Ancient Egypt: From Prehistory to the Islamic Conquest. Britannica Guide to Ancient Civilizations. Chicago: Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61530-572-8.

- Labrousse, Audran (1997). "Un bloc décoré du temple funéraire de la mère royale Néferhétephès". In Berger, Catherine; Mathieu, Bernard (eds.). Études sur l'Ancien Empire et la nécropole de Saqqâra : dédiées à Jean-Philippe Lauer. Orientalia monspeliensia (in French). Vol. 9. Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry. pp. 263–270. ISBN 978-2-84-269047-2.

- Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Philippe (2000). Les Complexes Funéraires d'Ouserkaf et de Néferhétepès. Bibliothèque d'étude, Vol. 130 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0261-3.

- Lansing, Ambrose (1926). "The Museum's Excavations at Lisht". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 21 (3, Part 2: The Egyptian Expedition 1924–1925): 33–40. doi:10.2307/3254818. JSTOR 3254818.

- Lauer, Jean-Phillipe; Flandrin, Philippe (1992). Saqqarah, une vie: entretiens avec Philippe Flandrin. Petite Bibliothèque Payot, 107 (in French). Paris: Payot. ISBN 978-2-22-888557-7.

- Legrain, Georges (1906). Statues et statuettes de rois et de particuliers (PDF). Catalogue Général des Antiquités Egyptiennes du Musée du Caire (in French). Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 975589. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05084-2.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Writings from the ancient world, no. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58-983736-2.

- Lichteim, Miriam (2000). Ancient Egyptian Literature: a Book of Readings. The Old and Middle Kingdoms, Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02899-9.

- "Limestone false door of Ptahshepses". Online catalog of the British Museum. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "List of Ancient Egyptian viziers". Digital Egypt for Universities. 2000. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Mac Farlane, Ann (1991). "Titles of sm3 + God and ḫt + God. Dynasties 2 to 10". Göttinger Miszellen. Göttingen: Seminar für Ägyptologie und Koptologie an der Universität Göttingen. 121: 77–100. ISSN 0344-385X.

- Málek, Jaromir (1992). "A Meeting of the Old and New. Saqqâra during the New Kingdom". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). Studies in Pharaonic Religion and Society. In Honour of J. Gwyn Griffiths. The Egypt Exploration Society. Occasional Publications. Vol. 8. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 57–76. ISBN 0-85698-120-6.

- Málek, Jaromir (2000a). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2160–2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Málek, Jaromir (2000b). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Mariette, Auguste (1885). Maspero, Gaston (ed.). Les mastabas de l'ancien empire : fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette (PDF). Paris: F. Vieweg. OCLC 722498663.

- Mark, Samuel (2013). "Graphical Reconstruction and Comparison of Royal Boat Iconography from the Causeway of the Egyptian King Sahure (c. 2487–2475 BC)". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 42 (2): 270–285. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12015. S2CID 162960720.

- Mazur, Suzan (4 October 2005). "Dorak Diggers Weigh In On Anna & Royal Treasure". Scoop. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27 – July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Mumford, G. D. (1999). "Wadi Maghara". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 1071–1075. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Mumford, Gregory (2006). "Tell Ras Budran (Site 345): Defining Egypt's Eastern Frontier and Mining Operations in South Sinai during the Late Old Kingdom (Early EB IV/MB I)". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 342 (342): 13–67. doi:10.1086/BASOR25066952. JSTOR 25066952. S2CID 163484022.

- Navrátilová, Hana; Arnold, Felix; Allen, James P. (2013). "New Kingdom Graffiti in Dahshur, Pyramid Complex of Senwosret III: Preliminary Report. Graffiti Uncovered in Seasons 1992–2010". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 49: 113–141. doi:10.5913/0065-9991-49-1-113. JSTOR 24555421.

- Pahor, Ahmes L.; Farid, Adel (2003). "Ni-Ankh-Sekhmet: first rhinologist in history". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 117 (11): 846–849. doi:10.1258/002221503322542827. PMID 14670142. S2CID 30009299.

- Peden, Alexander J. (2001). The graffiti of pharaonic Egypt : scope and roles of informal writings, c. 3100–332 B.C. Probleme der Ägyptologie. Vol. 17. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00-412112-6.

- Phillips, Jacke (1997). "Punt and Aksum: Egypt and the Horn of Africa". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 38 (3): 423–457. doi:10.1017/S0021853797007068. JSTOR 182543. S2CID 161631072.

- Redford, Donald B. (1986). "Egypt and Western Asia in the Old Kingdom". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 23: 125–143. doi:10.2307/40001094. JSTOR 40001094.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge London & New York. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.

- Routledge, Carolyn (2007). "The Royal Title nb U+0131rt-ḫt". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. American Research Center in Egypt. 43: 193–220. JSTOR 27801613.

- Rowland, Joanne (2011). "An Old Kingdom mastaba and the results of the continued excavations at Quesna in 2010". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 97: 11–29. doi:10.1177/030751331109700102. JSTOR 23269885. S2CID 190492551.

- Saghieh, Muntaha (1983). Byblos in the third millenium BC: a reconstruction of the stratigraphy and a study of the cultural connections. Archaeology and languages of the ancient Near East. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. OCLC 858367626.

- "Sahure and the god of the region of Coptos". 28 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Schmitz, Bettina (1976). Untersuchungen zum Titel s3-njśwt "Königssohn". Habelts Dissertationsdrucke: Reihe Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 2. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 978-3-7749-1370-7.

- Schneider, Thomas (2002). Lexikon der Pharaonen (in German). Düsseldorf: Patmos Albatros Verlag. ISBN 978-3-49-196053-4.

- "Seal impression bearing Sahure's cartouche from Buhen". Online catalog of the Petrie Museum. 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Sethe, Kurt Heinrich (1903). Urkunden des Alten Reichs (in German). wikipedia entry: Urkunden des Alten Reichs. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 846318602.

- "Short list of attestations of Sahure". Digital Egypt for Universities. 2000. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Smith, William Stevenson (1965). Interconnections in the Ancient Near-East: A Study of the Relationships Between the Arts of Egypt, the Aegean, and Western Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press. OCLC 510516.

- Smith, William Stevenson (1971). "The Old Kingdom of Egypt and the Beginning of the First Intermediate Period". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 1, Part 2. Early History of the Middle East (3rd ed.). London, New york: Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–207. ISBN 978-0521077910. OCLC 33234410.

- Sowada, Karin N. (2009). Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean During the Old Kingdom: An Archaeological Perspective. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Vol. 237. Fribourg, Switzerland: Academic Press Fribourg, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. ISBN 978-3-7278-1649-9.

- Spalinger, Anthony (1994). "Dated Texts of the Old Kingdom". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 21: 275–319. JSTOR 25152700.

- Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London; Boston: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0107-9.

- Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.

- Tallet, Pierre (2012). "Ayn Sukhna and Wadi el-Jarf: Two newly discovered pharaonic harbors on the Suez Gulf" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan. 18: 147–168.

- Tooley, Angela M. J. (1996). "Osiris Bricks". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. Sage Publications, Ltd. 82: 167–179. doi:10.1177/030751339608200117. JSTOR 3822120. S2CID 220269536.