Nochnitsa

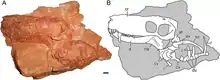

Nochnitsa is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids who lived during an uncertain stage of the Permian in what is now European Russia. Only one species is known, N. geminidens, described in 2018 from a single specimen including a complete skull and some postcranial remains, discovered in the red beds of Kotelnich, Kirov Oblast. The genus is named in reference to Nocnitsa, a nocturnal creature from Slavic mythology. This name is intended as a parallel to the Gorgons, which are named after many genera among gorgonopsians, as well as for the nocturnal behavior inferred for the animal. The only known specimen of Nochnitsa is one of the smallest gorgonopsians identified to date, with a skull measuring close to 8 cm (3.1 in) in length. The rare postcranial elements indicate that the animal's skeleton should be particularly slender.

| Nochnitsa Temporal range: Permian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype block, containing skull and partial skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Gorgonopsia |

| Genus: | †Nochnitsa Kammerer and Masyutin, 2018 |

| Type species | |

| † Nochnitsa geminidens Kammerer and Masyutin, 2018 | |

Phylogenetic analyzes published since its official description consider it as the most basal gorgonopsian known, due to several anatomical characteristics wo are not present in more or less derived genera. The Vanyushonki Member, the exact site from which Nochnitsa was discovered, would have been a moist, well-vegetated landscape, which would have been periodically flooded. The site contains numerous taxa of contemporary tetrapods, including other various therapsids. The presence of large therocephalians and the smaller size of Nochnitsa and its close relative Viatkogorgon indicate that the latter occupied comparatively small predatory roles.

Discovery and naming

The only known specimen of Nochnitsa, cataloged KPM 310, was discovered in 1994 by the Russian paleontologist Albert J. Khlyupin in the Red Beds of Kotelnich, located along the Vyatka River in Kirov Oblast, European Russia. This specimen was found more precisely in the Vanyushonki Member, a site already known for the discovery of other contemporary therapsids, including the gorgonopsian Viatkogorgon. The datation of this site is not clear, but it seems to date to the latest Guadalupian or early Lopingian epochs. After this discovery, the specimen was subsequently prepared in the Paleontological Museum of Vyatka by Olga Masyutina.[1]

In 2018, paleontologists Christian F. Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin named new genera of gorgonopsians and therocephalians discovered at Kotelnitch in two articles in the scientific journal PeerJ.[1][2] In their paper focusing on gorgonopsians, the specimen KPM 310 is identified as the holotype of a new genus and species, which they name Nochnitsa geminidens.[1]

Nochnitsa is named after the Nocnitsa, a nocturnal hag-like creature from Slavic mythology. Its name was intended as a parallel to the Gorgons, similarly hag-like creatures from Greek mythology, which are the namesake of many genera within Gorgonopsia and the clade as a whole. The name also reflects the nocturnal habits inferred for the genus. The type species name, geminidens, means "twin tooth" and refers to one of the autapomorphies of the species, postcanine teeth arranged in pairs.[1]

Description

Skull

Nochnitsa is small for a gorgonopsian, with a skull only 82 millimetres (3.2 in) long. It had a relatively long snout with five incisors, a canine, and six postcanine teeth on each side. The postcanine teeth are autapomorphic for the genus in being arranged in three pairs of closely placed teeth separated by longer diastemata. In each pair, the posterior tooth is larger. The mandible is relatively slender and lacks a strong "chin", unlike other gorgonopsians.[1]

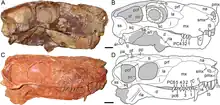

Postcranial skeleton

Although incompletely known, the holotype specimen of Nochnitsa contains part of the postcranial elements with the skull, including the cervical vertebrae, some dorsal vertebrae, and associated ribs. The right forelimb is also preserved and partially articulated.[1]

In the cervical vertebrae, the axial spine is broadly rounded and similar in morphology to that of other gorgonopsians. The dorsal vertebrae are preserved as central and transverse process fragments interspersed by the ribs. The ribs are also simple and elongated. The scapula is elongated, narrow and weakly curved, comparable to that of other gorgonopsians of similar size like Cyonosaurus, but different from the anteroposteriorly broadened scapular spines of Inostrancevia.[1]

The humerus is relatively slender, having a short, poorly developed delto-pectoral ridge, where the muscles attach to the upper arm. The radius and ulna, have a distinct distal curvature, and the distal tip of the radius forms a discrete differentiated rim of the shaft. No olecranon process is visible on the ulna, but it is possible that this is the result of a lesion.[lower-alpha 1] The preserved proximal carpal elements consist of the radial, the ulnar and two smaller, irregular elements that would probably represent the centralia. The ulnar is the longest carpus on the proximodistal side and is widened at its proximal and distal ends. The radial is a shorter and more rounded element. The possible centralia, although poorly preserved, appear to be weakly curved. The concave surface of the centralia would presumably have been articulated with the radial, based on the conditions of other gorgonopsians.[lower-alpha 2] Several small irregular bones between the proximal carpals and the metacarpals probably represent distal carpals, but these elements are too poorly preserved to be further identified. Based on their great length relative to the other manual elements, the two best preserved elements probably represent the third and fourth metacarpals, which are the longest of all other gorgonopsians for which the manus are known. A shorter but still elongated element may represent the fifth metacarpal. A semi-articulated set of poorly preserved bones appear to represent fingers, one potentially ending in the ungual. Based on the size of the phalanx-like elements, these probably correspond to the third and fourth fingers, disarticulated from the third and fourth metacarpals. These elements are too poor for a definitive count of the phalanges, and there is no clear evidence of the reduced disc-shaped phalanges commonly present in gorgonopsians.[1]

Classification

Nochnitsa is currently the most basal gorgonopsian known, and its position is justified by several plesiomorphic criteria, such as the lowered mandibular symphysis, the low and inclined front of the dentary bone (similar to those of therocephalians), as well as a surface and a row of elongated teeth. These mentioned features are not present in derived genera.[1] The 2018 analysis by Kammerer and Masyutin, although derived from a previous analysis conducted by one of the two authors,[3] is a major revision of the phylogeny of the gorgonopsians, discovering that the derived representatives are divided into two groups, of Russian and African origin.[1] The basal position of Nochnitsa in phylogenetic analysis of gorgonopsians is still recognized in later published studies.[4][5]

The following cladogram showing the position of Nochnitsa within Gorgonopsia follows Kammerer and Rubidge (2022):[5]

| Gorgonopsia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Paleoenvironment

Nochnitsa is known from the Kotelnich locality, which consists of a series of Permian red bed exposures along the banks of the Vyatka River in Russia. It is specifically from the Vanyushonki Member, which is the oldest rock unit in the Kotelnich succession, consisting of pale or brown mudstones (clay and silts, with some fine-grained sand) as well as gray mudstone, and dark red mudstone at the base of this exposure. These mudstones were possibly deposited from suspension in standing water bodies on floodplains or shallow ephemeral lakes, that remained flooded for short periods of time, but the exact environment has not yet been determined, due to the lack of a primary structure of the sediments. The presence of rootlets, roots and tree stumps would show that the landscape represented by the member of Vanyushonki would be relatively humid and well vegetated. Although the age of the Kotelnitch faunal complex is uncertain, it may date to the same age as those found in South Africa, which date from either the Late Middle Permian or the Early Late Permian.[1][6]

The Vanyushonki Member contains abundant fossils of tetrapods contemporary to Nochnitsa, most including numerous fossils often consisting of articulated and complete skeletons. Apart from its close relative Viatkogorgon, other therapsids from the locality include the anomodont Suminia and the therocephalians Chlynovia, Gorynychus, Karenites, Perplexisaurus, Scalopodon, Scalopodontes, and Viatkosuchus. The pareiasaur Deltavjatia is particularly abundant there, and the parareptile Emeroleter is present.[1][2][7] Fossil ostracods have also been found.[6]

Ecological niche

As the fossil record shows, the fauna of Kotelnitch was mainly dominated by the large therocephalians, and more specifically by Gorynychus and Viatkosuchus. These two taxa being much larger than Nochnitsa and Viatkogorgon, this indicates that the gorgonopsians occupied smaller predatory roles than the large therocephalians. This is further confirmed by the fact that several gorgonopsians having appeared after the extinction of the end of the Guadalupian reach considerably larger sizes than the two previously mentioned genera.[2][4] This type of ecological niche is also similar to that seen in the Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone in the Karoo Basin, South Africa, prior to the main round of gorgonopsian diversification there.[2] However, he noted that some Guadalupian gorgonopsians, notably Phorcys, are already larger in size, indicating that not all genera shared similar roles.[5]

See also

- Viatkogorgon, another gorgonopsian from the Vanyushonki Member.

Notes

- The proximal end of this feature is not complete and was partially replaced by mudstone during the fossilization of the holotype specimen.[1]

- A clear intermediate is not visible, as this element is generally small in gorgonopsians and may be absent or still buried in the fossil block containing the holotype specimen.[1]

References

- Christian F. Kammerer; Vladimir Masyutin (2018). "Gorgonopsian therapsids (Nochnitsa gen. nov. and Viatkogorgon) from the Permian Kotelnich locality of Russia". PeerJ. 6: e4954. doi:10.7717/peerj.4954. PMC 5995105. PMID 29900078.

- Christian F. Kammerer; Vladimir Masyutin (2018). "A new therocephalian (Gorynychus masyutinae gen. et sp. nov.) from the Permian Kotelnich locality, Kirov Region, Russia". PeerJ. 6: e4933. doi:10.7717/peerj.4933. PMC 5995100. PMID 29900076.

- Christian F. Kammerer (2016). "Systematics of the Rubidgeinae (Therapsida: Gorgonopsia)". PeerJ. 4: e1608. doi:10.7717/peerj.1608. PMC 4730894. PMID 26823998.

- Eva-Maria Bendel; Christian F. Kammerer; Nikolay Kardjilov; Vincent Fernandez; Jörg Fröbisch (2018). "Cranial anatomy of the gorgonopsian Cynariops robustus based on CT-reconstruction". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0207367. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207367. PMC 6261584. PMID 30485338.

- Christian F. Kammerer; Bruce S. Rubidge (2022). "The earliest gorgonopsians from the Karoo Basin of South Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 194: 104631. Bibcode:2022JAfES.19404631K. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2022.104631. S2CID 249977414.

- Michael J. Benton; Andrew J. Newell; Al'bert Y. Khlyupin; Il'ya S. Shumov; Gregory D. Price; Andrey A. Kurkin (2012). "Preservation of exceptional vertebrate assemblages in Middle Permian fluviolacustrine mudstones of Kotel'nich, Russia: stratigraphy, sedimentology, and taphonomy". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 319–320: 58–83. Bibcode:2012PPP...319...58B. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.01.005.

- Elena G. Kordikova; Albert J. Khlyupin (2001). "First evidence of a neonate dentition in pareiasaurs from the Upper Permian of Russia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 46 (4): 589–594. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

External links

- North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (8 June 2018). "'Monstrous' new Russian saber-tooth fossils clarify early evolution of mammal lineage". ScienceDaily.