Nuu-chah-nulth language

Nuu-chah-nulth (nuučaan̓uɫ),[3] a.k.a. Nootka (/ˈnuːtkə/),[4] is a Wakashan language in the Pacific Northwest of North America on the west coast of Vancouver Island, from Barkley Sound to Quatsino Sound in British Columbia by the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples. Nuu-chah-nulth is a Southern Wakashan language related to Nitinaht and Makah.

| Nuu-chah-nulth | |

|---|---|

| Nootka | |

| nuučaan̓uɫ, T̓aat̓aaqsapa | |

| Pronunciation | [nuːt͡ʃaːnˀuɬ] |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | West coast of Vancouver Island, from Barkley Sound to Quatsino Sound, British Columbia |

| Ethnicity | 7,680 Nuu-chah-nulth (2014, FPCC)[1] |

Native speakers | 130, (2014, FPCC (280 native speakers and 665 learners in 2021 [2]))[1] |

Wakashan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | nuk |

| Glottolog | nuuc1236 |

| ELP | Nuuchahnulth (Nootka) |

Nootka is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

It is the first language of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast to have documentary written materials describing it. In the 1780s, Captains Vancouver, Quadra, and other European explorers and traders frequented Nootka Sound and the other Nuu-chah-nulth communities, making reports of their voyages. From 1803–1805 John R. Jewitt, an English blacksmith, was held captive by chief Maquinna at Nootka Sound. He made an effort to learn the language, and in 1815 published a memoir with a brief glossary of its terms.

Name

The provenance of the term "Nuu-chah-nulth", meaning "along the outside [of Vancouver Island]" dates from the 1970s, when the various groups of speakers of this language joined together, disliking the term "Nootka" (which means "go around" and was mistakenly understood to be the name of a place, which was actually called Yuquot). The name given by earlier sources for this language is Tahkaht; that name was used also to refer to themselves (the root aht means "people").[5]

Phonology

Consonants

The 35 consonants of Nuu-chah-nulth:

| Bilabial | Alveolar[lower-alpha 1] | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyn- geal |

Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | sibilant | lateral | plain | labial | plain | labial | ||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | p | t | t͡s | t͡ɬ | t͡ʃ | k | kʷ | q | qʷ | ʔ | |

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | t͡sʼ | t͡ɬʼ | t͡ʃʼ | kʼ | kʷʼ | |||||

| Fricative | s | ɬ | ʃ | x | xʷ | χ | χʷ | ħ | h | |||

| Sonorant | plain | m | n | j | w | ʕ[lower-alpha 2] | ||||||

| glottalized[lower-alpha 3] | ˀm | ˀn | ˀj | ˀw | ||||||||

- Of the alveolar consonants, nasal and laterals are apico-alveolar while the rest are denti-alveolar.

- The approximant /ʕ/ is more often epiglottal and functions phonologically as a stop.

- Glottalized sonorants (nasals and approximants) are realized as sonorants with pre-glottalization. They are arguably conceptually the same as ejective consonants, though a preglottalized labial nasal could be analyzed as the stop–nasal sequence /ʔm/, as a nasal preceded by a creaky voiced (glottalized) vowel, or a combination of the two.

The pharyngeal consonants developed from mergers of uvular sounds; /ħ/ derives from a merger of /χ/ and /χʷ/ (which are now comparatively rare) while /ʕ/ came about from a merger of /qʼ/ and /qʷʼ/ (which are now absent from the language).[7]

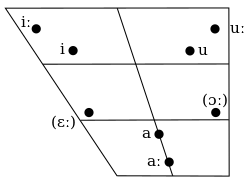

Vowels

Nuu-chah-nulth vowels are influenced by surrounding consonants with certain "back" consonants conditioning lower, more back vowel allophones.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| Close | iː | i | uː | u | ||

| Mid1 | (ɛː) | (ə) | (ɔː) | |||

| Open | aː | a | ||||

The mid vowels [ɛː] and [ɔː] appear in vocative forms and in ceremonial expressions. [ə] is a possible realization of /a/ after a glottalized sonorant.[7]

In the environment of glottalized resonants as well as ejective and pharyngeal consonants, vowels can be "laryngealized" which often means creaky voice.[7]

In general, syllable weight determines stress placement; short vowels followed by non-glottalized consonants and long vowels are heavy. In sequences where there are no heavy syllables or only heavy syllables, the first syllable is stressed.[7]

Nuu-chah-nulth has phonemic short and long vowels. Traditionally, a third class of vowels, known as "variable length" vowels, is recognized. These are vowels that are long when they are found within the first two syllables of a word, and short elsewhere.

Grammar

Nuu-chah nulth is a polysynthetic language with VSO word order.

A clause in Nuu-chah-nulth must consist of at least a predicate. Affixes can be appended to those clauses to signify numerous grammatical categories, such as mood, aspect or tense.

Aspect

Aspects in Nuu-chah-nulth help specify an action's extension over time and its relation to other events. Up to 7 aspects can be distinguished:[8]

| Aspect | Affix |

|---|---|

| Momentaneous | –(C)iƛ, –uƛ |

| Inceptive | –°ačiƛ, –iičiƛ |

| Durative | –(ʔ)ak, –(ʔ)uk, –ḥiˑ |

| Continuative | –(y)aˑ |

| Graduative | [lengthens the stem's first vowel and shortens its second one] |

| Repetitive | –ː(ƛ)–ː(y)a |

| Iterative | R–š, –ł, –ḥ |

Where each "–" signifies the root.

Tense

Tense can be marked using affixes (marked with a dash) and clitics (marked with an equal sign).

Nuu-chah-nulth distinguishes near future and general future:

| General future | Near future |

|---|---|

| =ʔaqƛ, =ʔaːqƛ | –w̓itas, –w̓its |

The first two markings refer to a general event that will take place in the future (similar to how the word will behaves in English) and the two other suffixes denote that something is expected to happen (compare to the English going to).

Past tense can be marked with the =mit clitic that can itself take different forms depending on the environment and speaker's dialect:

| Environment | Clitic | Example (Barkley dialect) | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consonant–vowel stem | =mi(t), =nit | waa → waamit | said |

| Long vowel, /m/, /n/ | =mi(t), =nt | saasin → saasinmit | dead hummingbird |

| Short vowel | =imt, =int, =mi(t), =um(t) | ciiqciiqa → ciiqciiqimt | spoke |

| Consonant | =it, =mi(t), =in(t) | wiikapuƛ → wiikapuƛit | passed away |

| =!ap | =mi(t), =in(t), =!amit | hił=!ap → hiłʔamit | hosted at |

| =!at | =mi(t), =in(t), =!aːnit, =!anit | waa=!at → waaʔaanit | was told |

Mood

Grammatical mood in Nuu-chah-nulth lets the speaker express the attitude towards what they're saying and how did they get presented information. Nuu-chah-nulth's moods are:

| Mood | Affix |

|---|---|

| Absolutive | =∅ |

| Indicative | =maˑ |

| Assertive | =ʔiˑš |

| Indefinite relative | =(y)iː, =(y)iˑ |

| Definite relative | =ʔiˑtq, =ʔiˑq |

| Subordinate | =qaˑ |

| Dubitative relative | =(w)uːsi |

| Conditional | =quː, =quˑ |

| Quotative | =waˑʔiš, =weˑʔin |

| Inferential | =čaˑʕaš |

| Dubitative | =qaˑča |

| Purposive | =!eeʔit(a), =!aːḥi |

| Interrogative | =ḥaˑ, =ḥ |

| Imperative | =!iˑ |

| Future imperative | =!im, =!um |

| go–imperative | =čiˑ |

| come–imperative | =!iˑk |

| Article | =ʔiˑ |

| Quotative article | =čaˑ |

Not counting the articles, all moods take person endings that indicate the subject of the clause.

Vocabulary

The Nuu-chah-nulth language contributed much of the vocabulary of the Chinook Jargon. It is thought that oceanic commerce and exchanges between the Nuu-chah-nulth and other Southern Wakashan speakers with the Chinookan-speaking peoples of the lower Columbia River led to the foundations of the trade jargon that became known as Chinook. Nootkan words in Chinook Jargon include hiyu ("many"), from Nuu-chah-nulth for "ten", siah ("far"), from the Nuu-chah-nulth for "sky".

A dictionary of the language, with some 7,500 entries, was created after 15 years of research. It is based on both work with current speakers and notes from linguist Edward Sapir, taken almost a century ago. The dictionary, however, is a subject of controversy, with a number of Nuu-chah-nulth elders questioning the author's right to disclose their language.

Dialects

Nuu-chah-nulth has 12 different dialects:

- Ahousaht [ʕaːħuːsʔatħ]

- Ehattesaht (AKA Ehattisaht) [ʔiːħatisʔatħ]

- Hesquiat [ħiʃkʷiːʔatħ]

- Kyuquot [qaːjʼuːkʼatħ]

- Mowachaht [muwat͡ʃʼatħ]

- Nuchatlaht [nut͡ʃaːɬʔatħ]

- Ohiaht (AKA Huu.ay.aht) [huːʔiːʔatħ]

- Clayoquot (AKA Tla.o.qui.aht) [taʔuːkʷiʔatħ]

- Toquaht [tʼukʼʷaːʔatħ]

- Tseshaht (AKA Sheshaht) [t͡ʃʼiʃaːʔatħ]

- Uchuklesaht (AKA Uchucklesaht) [ħuːt͡ʃuqtisʔatħ]

- Ucluelet (AKA Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ) [juːɬuʔiɬʔatħ]

Translations of the First Nation names

- Nuu-Chah-Nulth - "all along the mountains and sea." Nuu-chah-nulth were formerly known as "Nootka" by colonial settlers (but they prefer not to be called that, rather Nuu-chah-nulth which better explains how each First Nation is connected to the land and the sea). Some of the names following (Ditidaht, Makah) are not part of the Nuu-chah-nulth political organization, however; all are atḥ (people). The term nuučaanułatḥ[9] is also used, meaning "people all along the mountains and the sea."

- Ahousaht - People of an open bay/People with their backs to the mountains and lands

- Ucluelet - People with a safe landing place for canoes.

- Ehattesaht - People of a tribe with many clans

- Checkleset – People from the place where you gain strength

- Hesquiaht - People who tear with their teeth

- Kyuquot - Different people

- Mowachaht - People of the deer

- Muchalaht – People who live on the Muchalee river

- Nuchatlaht - People of a sheltered bay

- Huu-ay-aht - People who recovered

- Tseshaht - People from an island that reeks of whale remains

- Tla-o-qui-aht - People from a different place

- Toquaht - People of a narrow passage

- Uchucklesaht - People of the inside harbour

- Ditidaht - People of the forest

- Hupacasaht - People living above the water

- Quidiishdaht (Makah) - People living on the point

- Makah - People generous with food

Translations of place names

Nuuchahnulth had a name for each place within their traditional territory. These are just a few still used to this day:

- hisaawista (esowista) – Captured by clubbing the people who lived there to death, Esowista Peninsula and Esowista Indian Reserve No. 3.

- Yuquot (Friendly Cove) – Where they get the north winds, Yuquot

- nootk-sitl (Nootka) – Go around.

- maaqtusiis – A place across the island, Marktosis

- kakawis – Fronted by a rock that looks like a container.

- kitsuksis – Log across mouth of creek

- opitsaht – Island that the moon lands on, Opitsaht

- pacheena – Foamy.

- tsu-ma-uss (somass) – Washing, Somass River

- tsahaheh – To go up.

- hitac`u (itatsoo) – Ucluelet Reserve.

- t’iipis – Polly’s Point.

- Tsaxana – A place close to the river.

- Cheewat – Pulling tide.[10]

Status

Using data from the 2021 census, Statistics Canada reported that 665 individuals could conduct a conversation in Nuu-chah-nulth. This represents a 23.% increase over the 2016 census. The total included 280 speakers who reported the language as a mother tongue. [11]

Resources

A Ehattesaht iPhone app was released in January 2012.[12] An online dictionary, phrasebook, and language learning portal is available at the First Voices Ehattesaht Nuchatlaht Community Portal.[13]

See also

- Nuu-chah-nulth alphabet

- Nuu-chah-nulth people

- Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council

- Nootka Jargon, a Nuu-chah-nulth-based predecessor of Chinook Jargon

- Nitinaht language

- Makah

Notes

- Nuu-chah-nulth at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- "Indigenous languages across Canada". Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- "About the Language Program". Hupač̓asatḥ. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- Some account of the Tahkaht language, as spoken by several tribes on the western coast of Vancouver island , Hatchard and Co., London, 1868

- Carlson, Esling & Fraser (2001:276)

- Carlson, Esling & Fraser (2001:277)

- Werle, Adam (March 2015). "Nuuchahnulth grammar reference for LC language notes" (PDF).

- "First Nations". Friends Of Clayoquot Sound. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Source: Ha-shilth-sa newspaper, 2003. All translations were compiled with consultation from Nuuchahnulth elders. Ha-shilth-sa (meaning 'interesting news') is the official newspaper for the Nuu-chah-nulth nation.

- "Indigenous languages across Canada". Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- "FirstVoices Apps". FirstVoices. Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- "FirstVoices: Ehattesaht Nuchatlaht Community Portal". Retrieved 2012-10-04.

References

- Carlson, Barry F.; Esling, John H.; Fraser, Katie (2001), "Nuuchahnulth", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 31 (2): 275–279, doi:10.1017/s0025100301002092

- Kim, Eun-Sook. (2003). Theoretical issues in Nuu-chah-nulth phonology and morphology. (Doctoral dissertation, The University of British Columbia, Department of Linguistics).

- Nakayama, Toshihide (2001). Nuuchahnulth (Nootka) morphosyntax. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09841-2

- Sapir, Edward. (1938). Glottalized continuants in Navaho, Nootka, and Kwakiutl (with a note on Indo-European). Language, 14, 248–274.

- Sapir, Edward; & Swadesh, Morris. (1939). Nootka texts: Tales and ethnological narratives with grammatical notes and lexical materials. Philadelphia: Linguistic Society of America.

- Adam Werle. (2015). Nuuchahnulth grammar reference for LC language notes. University of Victoria

- Sapir, Edward; & Swadesh, Morris. (1955). Native accounts of Nootka ethnography. Publication of the Indiana University Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics (No. 1); International journal of American linguistics (Vol. 21, No. 4, Pt. 2). Bloomington: Indiana University, Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics. (Reprinted 1978 in New York: AMS Press, ISBN).

- Shank, Scott; & Wilson, Ian. (2000). Acoustic evidence for ʕ as a glottalized pharyngeal glide in Nuu-chah-nulth. In S. Gessner & S. Oh (Eds.), Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Salish and Neighboring Languages (pp. 185–197). UBC working papers is linguistics (Vol. 3).

External links

- An extract from the forthcoming Nuuchahnulth Dictionary

- Bibliography of Materials on the Nuuchanulth Language (YDLI)

- Nuuchahnulth (Nootka) (Chris Harvey’s Native Language, Font, & Keyboard)

- The Wakashan Linguistics Page

- Nootka Language and the Nootka Indian Tribe at native-languages.org

- Nuu-chah-nulth (Intercontinental Dictionary Series)