Isaccea

Isaccea (Romanian: [iˈsaktʃe̯a]; Turkish: İshakçı) is a small town in Tulcea County, in Northern Dobruja, Romania, on the right bank of the Danube, 35 km north-west of Tulcea. According to the 2021 census, it has a population of 4,408.

Isaccea | |

|---|---|

Town hall of Isaccea | |

Coat of arms | |

Location in Tulcea County | |

Isaccea Location in Romania | |

| Coordinates: 45°16′11″N 28°27′35″E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Tulcea |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2024) | Anastase Moraru[1] (PSD) |

| Area | 103.97 km2 (40.14 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Population (2021-12-01)[2] | 4,408 |

| • Density | 42/km2 (110/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET/EEST (UTC+2/+3) |

| Postal code | 825200 |

| Area code | (+40) 02 40 |

| Vehicle reg. | TL |

| Website | www |

The town has been inhabited for thousands of years, as it is one of the few places in all the Lower Danube that can be easily forded and thus be an easy link between the Balkans and the steppes of Southern Ukraine and Russia, north of the Black Sea. The Danube was for a long time the border between the Romans, later Byzantines and the "barbarian" migrating tribes in the north, making Isaccea a border town, conquered and held by dozens of different peoples.

Geography

The town has under its administration 103.97 km2, of which 3.69 km2 are inside the residential areas.

| Type of usage | Area | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| agricultural use | 45.02 km2 | cereals, orchards, vineyards and pastures |

| floodplain | 32.97 km2 | along the Danube |

| forest | 22.76 km2 | |

| built-up areas | 2.92 km2 | buildings and roads |

The town is divided into three settlements: Isaccea proper (4,789 inhabitants) and two villages, Revărsarea (563 inhabitants) and Tichilești (10 inhabitants).

The Tulcea – Brăila roadway (DN22/E87) crosses the town.

The town is located in near to the Măcin Mountains and Dobruja Plateau (in the south) and the Danube (in the north). Many lakes could once be found in the town, but some of them were desiccated by the Communist authorities in order to use the terrain for agriculture. This initiative lacked success, since the soil of the area proved to be not very fertile. Some larger lakes still remain: Saun, Telincea, Rotund, Ghiolul Pietrei, Racova. In April 2006, the dyke which protected this terrain failed and the Danube flooded again the areas which used to be wetlands.

Along the Danube there is a floodplain, which gets inundated every spring, bringing fresh water to the lakes and the marshlands.[4] The largest lake in Isaccea is "Lacul Rotund" (literally, Round Lake), having an area of 2.19 km2 and a volume of 2.0 million m3.[4]

Tichilești

Tichilești was founded as a monastery of Tichilești, with time becoming a leper colony. A legend says the monastery was founded by one of the Cantacuzino princesses who was affected by leprosy. Another theory of the history the settlement is that a group of Russian refugees (see Lipovans) settled there and founded the monastery, but soon became outlaws who were eventually caught. In 1918, a part of the lepers moved to Bessarabian town of Izmail. Following a 1926 newspaper article, a hospital was built in 1928 at the monastery. In 1998, there were 39 people in the settlement, and according to the 2002 census, there were 22 people, most of them having an age of more than 60 years.[5] By 2019, there were only 9 people.[6]

Revărsarea

Revărsarea was founded after the 1877 War of Independence, being settled by war veterans and colonists, the village being built in the place of a forest which has been cleared. It had several other names since: Piatra Calcată, Principele Nicolae (named after Prince Nicholas of Romania) and Ștefan Gheorghiu (named after Ștefan Gheorghiu, a trade unionist).[7]

Name

Possibly the earliest mentioning is in De Administrando Imperio (around 950) of Constantine Porphyrogenitus. It talks about six deserted cities between the Dniester and Bulgaria, among them being Saka-katai, katai being most likely a transcription of a Pecheneg word for "city". The name Saka could in turn be derived from Romanian sacă/seacă, meaning "barren", however both the identification of the city with Isaccea and the etymology are mere speculations.[8]

The first clear reference to this name was in the 11th century, when there was a local ruler from Vicina named Σακτζας (Saktzas, probably Saccea / Sakça), for the first time used by Byzantine Anna Comnena in her Alexiad.[9] Nicolae Iorga presumed that the ruler was Romanian,[10] however "-ça" (-cea) could also indicate a Turkic suffix.

The 14th-century Arab geographer Abu'l-Fida mentions the town under the name "Saecdji", which was a territory of the "Al-Ualak" (Wallachs).

The initial "i" in the name was added during the Ottoman domination, due to the same feature of the Turkish language that transformed "Stanbul" to "Istanbul". Some local legends claim that the town was named after a certain Isac Baba, however the other explanation is more likely to be true, as the name of the town initially lacked the "i".

Other historical names include:

- Noviodunum (Latin); Νοβιόδοῦνος, Noviodounos (Greek) - ancient name of Celtic origin, meaning "New Fort" ("nowyo(s)" means "new", while "dun" is Celtic for "hillfort" or "fortified settlement").[11][12]

- Genucla - Dacian name of a possibly nearby settlement, derived from Proto-Indo-European *genu, knee.

- Oblucița (Romanian); Облучица, Obluchitsa (Bulgarian); Obluczyca (Polish) - Slavic name derived from the word "oblutak", that means a rock that was shaped by water into a rounder form.

- Vicina - Genoese name of a port built by Genoese traders as an outpost of the Byzantine Empire. Its location is still unknown, but one of the theories is that it was around Isaccea.

History

Ancient history

The land where the town is now has been inhabited since prehistoric times: the remains of a neolithic settlement, belonging to the Boian-Giulești culture (4100–3700 BC) were found in the northwestern part of the town, in a place known as "Suhat".[13][14]

The neolithic culture was succeeded by the Getae culture with Hellenistic influences.[14] The Celts expanded their territory from Central Europe, reaching Isaccea in the 3rd century BC (see Gallic invasion of the Balkans) and giving the ancient name of town, "Noviodunum", as well as of other names in this region, such as Aliobrix, on the other side of the Danube and Durostorum further south in Dobruja.[11][15]

In 514 BC, Darius I of Persia fought here a decisive battle against the Scythians. A trade post was also built in this town by the Greeks. Greek authors such as Ptolemy and Hierocles name it a "polis".[16]

The town was taken by the Romans in 46 AD and became part of the Moesia province.[17] It was fortified and became the most important military and commercial city in the area, becoming a municipium.[18] Its ruins are located 2 km to the east of modern Isaccea on a hill known as Eski-Kale (Turkish for "Old Fortress").[13]

In Noviodunum was the main base of the lower Danube Roman fleet named Classis Flavia Moesica, then temporarily the headquarters of the Roman Legio V Macedonica (106-167), Legio I Italica (167-) and Legio I Iovia.[13][19]

Around 170 AD, the Roman settlements in Dobruja were attacked by the Dacian tribe of the Costoboci, who lived in what is now Moldavia, their attack being visible in the archeological remains of Noviodunum.[20] Further attacks continued in the 3rd century, this time by the combined forces of the Dacian tribe of the Carpi and of the Goths, the decisive battle being probably in 247.

The violent invasions of the Carpi, who plundered the cities and enslaved their inhabitants, left behind many archaeological traces, including buried coin hoards and signs of destruction.[21] The fortress of Noviodunum was probably destroyed during the raids of the Goths and Heruli, during the rule of Gallienus (267), buried hoards being found near it, including a larger treasure containing 1071 Roman coins.[13][16] The raids left Noviodunum, like other urban centres in the area, depopulated, only returning to its original state toward the end of the 3rd century.[21]

During the rule of Constantine I (306-337), the Noviodunum fortress was rebuilt as part of a bigger project of restoring the Empire's borders along the Lower Danube.[22]

By the 4th century, the town also became a Christian centre. The tomb of four Roman Christian martyrs, discovered in September 1971 in nearby Niculiţel, bears the names Zotikos, Attalos, Kamasis and Philippos. They were probably killed in Noviodunum during campaigns of persecutions of early Christians by Diocletian (303-304) and Licinius (319-324),[23] being taken out of the city and buried as martyrs by the local Christians.[15]

In 369 an important battle was fought between the Romans, led by emperor Flavius Valens and the Thervingi led by Athanaric. Valens' army crossed the river at Noviodunum (Isaccea) using a boat bridge and met the Gothic army in Bessarabia. Although Valens obtained a victory for the Romans, they retreated (possibly because of the lateness of the season)[24] and the Goths asked for a peace treaty, which was signed in the middle of the Danube, the Goths taking an oath to never set foot on Roman soil.[25]

After the division of the Roman Empire, it became part of the Byzantine Empire and it was the most important Byzantine naval base on the Danube. Valips, a chieftain of Germanic Rugians (who were allies of the Huns), took Noviodunum sometimes between 434 and 441 and it was included in the Hunnish Empire,[26] the area becoming a fiefdom of the Hunnish leader Hernac after Attila's death.[27]

The Slavs began to settle in early 6th century and possibly the earliest reference to their settlement in the town is Jordanes' book (written in 551) The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, which mentioned Noviodunum as an extremity of the region were the "Sclaveni" lived.[28] The town continued to be under Byzantine rule, but it suffered the raids from other nomadic peoples, such as the Kutrigurs (559) and Avars (561-562).[27] In the mid-6th century, Justinian I built new fortifications and made it an episcopal see.[16]

During the rule of Phocas (602-610), a massive number of Avars and Slavs crossed the Byzantine border and although their presence protected the empire from other nomads, their control became just formal, until in 681, the Byzantines recognised the First Bulgarian Empire and gave up their claims for the Scythia Minor province.[27] For more than 300 years, Isaccea faded from history and there is no historical or archaeological evidence that the place was even inhabited.[29]

Mediaeval history

Around 950, Constantine Porphyrogenitus talks of six desert cities in the area, one being named Saka-katai, which could be the earliest mentioning of the town after it was lost to the migrating people during the Dark Age.

In 971, Isaccea was once again included in the Byzantine Empire and the walls of kastron were reinforced. In 1036, the Pechenegs being driven southward by the Cumans, settled in Scythia Minor, including in this city, fact backed by archeological evidence, such as leaf-shaped pendants, characteristic to them.[30] The Pechenegs traded with the Byzantines, which led to a growth in the economic life of the region, as shown by the number of coins found in Isaccea, reaching 700 coins for the period of 1025–1055.[31] However, the Pechenegs were eventually assimilated and faded from history.

The Byzantines regained control of Isaccea toward the end of the 10th century: a seal of Leo Nicerites, the governor of Paristrion, was found at Isaccea.[32] Around 1100, a double-curtain wall was built in Isaccea.[33]

In the mid-12th century, Isaccea was devastated by Cuman attacks and it was completely rebuilt. In the second half of the 12th century it became the most important Byzantine military base in the region, suggested by the number of imperial seals found there: a seal of Isaac II Angelos (1185–1195) and one of John Vatatzes, the head of the Imperial Guard under Manuel I Komnenos (1143–1180).[34]

According to Arab chronicles, the Nogai Tatars settled in the town in the late 13th century.[35] Between 1280 and 1299, the town was Nogai Khan's base of operation in his campaigns against the Bulgarian city of Tarnovo. At the time, the city was a local Muslim centre and the residence of the famous Turkish dervish Sarı Saltuk, who has been associated with Nogai Khan's conversion to Islam.[36]

Arab geographer Abulfeda mentioned the town, placing it in the territory of the "Al-Ualak" (Wallachs), having a population mostly Turkic and being ruled by the Byzantines.[37] A Byzantine despotate existed in Northern Dobruja with Isaccea as its centre, which sometimes between 1332 and 1337 became a vassal of the Golden Horde of Nogais under the name "Saqčï".[38]

The Tatars held an important mint in Isaccea, which minted coins marked with Greek and Arabic letters between the years 1286 and 1351. Various types of silver and copper coins were minted, including coins bearing the mark of the Golden Horde with the names of the khans as well as the names of Nogai Khan and his son Čeke (minted between 1296 and 1301).[39]

In the late 14th century it was ruled by Mircea cel Bătrân of Wallachia, being held until one year before his death. In 1417, the town was conquered, together with other fortresses on the Danube, by the Ottomans,[40] who built a fort defended by a garrison as part of the Danubian frontier established by Mehmet I.[41]

The town was regained by Vlad Țepeș in 1462 during his campaigns against the Ottoman Empire, massacring the local Muslim Bulgarian and Turkish population (who were expected to side with the Turks), killing 1350 people in Isaccea and Novoselo,[42] out of more than 23,000 people in all Bulgaria. In a letter to Matthias Corvinus, dated February 11, 1462, he stated:

I have killed men and women, old and young, who lived at Oblucitza [old name of Isaccea] and Novoselo, where the Danube flows into the sea, up to Rahova, which is located near Chilia, from the lower Danube up to such places as Samovit and Ghighen. We killed 23,884 Turks and Bulgars without counting those whom we burned in homes or whose heads were not cut by our soldiers....Thus your highness must know that I have broken the peace with him [the sultan].[43]

In 1484, it was taken again by the Ottomans, being included in the Silistra (Özi) Province, which comprised Dobruja, much of present-day Bulgaria, and later also Budjak and Yedisan.

Țepeș's massacre and destruction completely changed the ethnic composition and the appearance of Isaccea, which remaining throughout the 16th century a small, largely Christian, village.[44] Bayazid II's conquest of Kilia and Akkerman removed the danger from the north, as did Mehmet II's victories against Wallachia remove the threat from the west, and as such, the Sultan saw no reason to rebuild the fortress of Isaccea, nor the settlement of a garrison.[45]

In 1574, Voivode Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit of Moldavia sent Pârcălab Ieremia Golia with an army to Oblucița (Isaccea) to prevent the Ottoman army from fording the river. However, Golia betrayed Ioan for a sum of 30 gold bags, thus leading to the defeat of the Moldavian army and the execution of Ioan.[46]

By the beginning of the 16th century, a new danger arose for the Ottoman border on the Lower Danube: the Cossacks from Ukraine, who, in 1603, reached Oblucița and set the town on fire.[47] Sultan Osman II began a series of campaigns against the Cossacks and, as part of his fortification of the border, in 1620, a new fort was built in Isaccea, but in a different place.[48]

On 6 October 1598, Mihai Viteazul defeated the Ottoman army at Oblucița, recapturing the town. The following year, in March 1599, the Ottomans' army took back the town and went into incursions into Wallachia, Mihai's response being to go beyond the Danube and attack the town of Oblucița.[49] After Mihai's death in 1601, the town was regained by the Ottomans.

In December 1673, at the Ottoman army camp in Isaccea, Dumitrașcu Cantacuzino was chosen Prince of Moldavia.[50]

Modern history

During the wars between the Russians and the Turks of the 18th and 19th centuries, it occupied by each side for several times, being several times set on fire and almost completely destroyed.

During the Prut River Campaign (1711), the Russians tried to block the Ottomans crossing of the Danube at Isaccea, but failing to do so, the two armies clashed at Stănilești, on the Prut River.[51]

Isaccea was besieged three times in the 1770s: in 1770, 1771 and 1779: in 1771, it was conquered by the Russians in the wake of the Battle of Kagul, the Russians destroying the fortifications and the mosques. Unlike many other settlements in the region, it was not razed, but after ten years of devastating war, only 150 houses were still standing.

Near Isaccea, the Russian flotilla commanded by José de Ribas clashed with and captured the Turkish flotilla during the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792). The Ottoman defenders of Isaccea fled, destroying the fortifications left behind. After a while, the Turkish regained it, being recaptured by Lieutenant-General Galitzine in March 1791.[52]

During the Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829), the Russian Army crossed the Danube at Isaccea, but the Ottoman garrison of the Isaccea fortress surrendered without resistance.[52] A local legend explains the existence of a mound near the old bridge this way: during the Russo-Turkish wars a Turkish general accused of treason was buried alive (horse included), each of his soldiers being forced to bring a fez full of dirt and throw it over the general.

In 1853, during the Crimean War, it was besieged again by the Russians, before the war theatre moved to Crimea. In December of that year, The Times of London noted that "Isaktchi" had a fortified castle and a garrison of 1500 men, but that it was simply a "port of observation" on the river.[53]

After the war, a European Danube Commission was established, which decided to clear the silt at the mouths of the Danube, between Isaccea and the Black Sea; however, the increased trade on the Danube affected Isaccea but little.

At the beginning of the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878, the Russians were able to take advantage of Romania's railways and mass a great number of troops in Galați. 4000 Russian troops crossed the Danube 14 km south of Măcin and were victorious on June 22, 1877, against the Ottoman garrison. The Russian victories intimidated the commander of the Isaccea garrison and the Ottoman troops withdrew from the town, leaving the whole northern part of Dobruja to the Russian armies.[54] Many of the Muslims in the towns of this area fled from the early days of the conflict.[54] The city was captured without battle on June 26, 1877, by the 14th Army under the leadership of Major-General Yanov.[52]

Following the Russian-Romanian victory in the war against the Ottoman Empire, Russia took back from Romania the Southern Bessarabia region and as compensation, the newly independent state of Romania received the region of Dobruja, including the town of Isaccea.[55]

In 1915, Nicolae Iorga described Isaccea as "a gathering of small and humble houses spread over a hill slope".

During World War I, Dobruja was in the areas of operation of a force formed by the Russian and Romanian armies. The first Russian unit crossed the Danube at Isaccea on the day when war was declared (August 27, 1916) and began their deployment toward Bulgaria, an ally of the Central Powers.[56]

Following the failure of the Flămânda Offensive, the Russians began retreating,[56] soon as north as Isaccea. The town was defended by the Romanian and Russian troops against the German offensive, but it was lost on December 24, 1916.[57] Following its defeat, Romania signed the Treaty of Bucharest, by the term of which, Romania ceded the southern part of Dobruja to Bulgaria, while the rest (including Isaccea), was ceded to the Central Powers.[58] The Treaty was voided by the terms of the Armistice of November 11, 1918 and Isaccea was thus returned to Romania.[59]

In February 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, thousands of Ukrainians crossed by ferry into Romania at Isaccea in search of refuge.[60]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1828 | 784 | — |

| 1912 | 4,112 | +424.5% |

| 1930 | 4,576 | +11.3% |

| 1948 | 4,653 | +1.7% |

| 1956 | 5,203 | +11.8% |

| 1966 | 5,059 | −2.8% |

| 1977 | 5,347 | +5.7% |

| 1992 | 5,639 | +5.5% |

| 2002 | 5,374 | −4.7% |

| 2011 | 5,026 | −6.5% |

| [61] | ||

The majority of the population is formed by Orthodox Christian Romanians, but there is also a 4% minority of Muslim Turks. In 1516, it was a purely Christian village, with 163 households;[62] in 1518, there were 256 Christian houses.[63] By the end of the 16th century, the town grew to 332 Christian households and 25 Muslim households, of which half were new converts.[62]

Ethnic structure

In 1828, there were 363 Romanians, 183 Turks, 163 Cossacks, 29 Greeks, 20 Jews and 3 Armenians.[13]

According to the 2011 Romanian census, the ethnic structure of the population of Isaccea was the following:

| Ethnicity | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Romanian | 4,638 | 93.6% |

| Turkish | 90 | 1.81% |

| Ukrainian | 11 | 0.22% |

| Roma | 209 | 4.21% |

Religion

| Religion | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Orthodoxy | 5,099 | 94.88% |

| Islam | 223 | 4.14% |

| Baptists | 30 | 0.55% |

| Old Calendarists | 14 | 0.26% |

| Other/none | 8 | 0.17% |

Government

The city government is headed by a mayor (primar), while the decisions are approved and discussed by the local council (consiliu local) made up of 15 elected councillors. From 1996 to 2012, the mayor of Isaccea was Ilie Petre, from the Democratic Liberal Party, who was re-elected for a fourth term in the 2008 local elections, winning in the second round by earning 61.46% of votes against Anastase Moraru, a candidate of the Social Democratic Party.[64] At the 2012 local elections, Moraru defeated Ilie.[65] Moraru was re-elected in 2016[66] and 2020.[1]

Since September 2020, the local council members belong to the following parties:[1]

Economy

The town has long been a station in the trade between the eastern Mediterranean and the continental eastern Europe. The Greeks built their first trade post around 2700 years ago and trade continued after the Roman and later Byzantine and Ottoman takeovers. In the 16th century, the town was located on the Moldavian-Ottoman border and its bazaar was one of the four most important trading posts in the Dobruja, with tradesmen coming from distant places, such as Chios or Ragusa.[67] The main traded goods were cattle, sheep, wine, cloth and wood.[63] The town lost its influence in the 19th century, as the sea and river transport was mostly replaced by train and later road transport and as the Danube traffic navigates on the Danube-Black Sea Canal.

Much of the local economy is based on agriculture, especially animal husbandry and fishing. The town's farms have a number of 2595 sheep, 728 cows, 510 pigs, 240 horses and 16,000 birds.[68] Industry is based on extraction of rock from a nearby quarry and woodworking, a tobacco processing factory and a winery.

Since 2004, the town is also home for a beluga reproduction research station, financed by the Romanian state. The world's first in vitro fertilisation research station for the beluga, it is fish farm, but also raises beluga to be freed into the Danube, freeing around 3000 belugas.[69]

The town is also a port on the Danube, having two mooring places for ships. It is mostly used for loading cereals and stone onto cargo ship.[70]

Isaccea is the entry point in Romania of the Isaccea-Negru Vodă gas pipeline (built between 2000 and 2002 to replace a smaller pipeline built in the 1980s) linking Ukraine and Bulgaria, bringing natural gas from Russia to Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. It has a diameter of 1200 mm and a capacity of 28 billion m³/year.[71] The town is also the entry point of the 400 kV Isaccea-Vulcăneşti electrical transmission line, through which Romania imports electricity from the Russian-owned Cuciurgan powerplant in the Transnistria region of Moldova.[72]

A sewage treatment plant is going to be built in Isaccea by 2012, funded 80.2% from the Cohesion Funds from the European Union.[73]

Local attractions

- The 2000-year-old ruins of the Roman fortress of Noviodunum

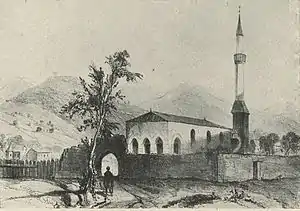

- The Isaccea Mosque, a 17th-century Turkish mosque, that has a 25-meter high minaret

- The 18th century "Saint George" Orthodox Church

- Isaac Baba's grave, believed by the local Muslims to be the founder of the town.

- The Cocoș Monastery, located 6 km south of the town centre

Natives

- Paul Barbă Neagră (1929–2009), film director

- George Curcă (born 1981), footballer

Notes

- "Results of the 2020 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- "Populaţia rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (XLS). National Institute of Statistics.

- Isaccea city hall website - Agriculture Archived 2008-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- National Institute of Statistics, "Anuarul statistic al judeţului Tulcea 2006" Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, p. 6

- "Ultimul lazaret", in Ziua March 21, 2006

- "Tichilești: Viața ultimilor bolnavi de lepră din România". Ziarul de Investigații (in Romanian). 2019-08-09. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- Primăria Isaccea: Aşezare (at the website of the city hall)

- Stelian Brezeanu Toponymy and ethnic Realities at the Lower Danube in the 10th Century, in "Annuario. Istituto Romeno di Cultura e Ricerca Umanistica, Venezia", 2002, (OCLC 85762872), p. 41–50

- Alexiad, Book Six

- Nicolae Iorga, Les premières cristallisations d'état des Roumains, Acadèmie Roumaine, Bulletin de la Section Historique (OCLC 73198609), V-VIII (1920), p. 33-46

- D.M. Pippidi et al., (1976) Dicționar de istorie veche a României, Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică (OCLC 251847977), p 149; entry: Celți

- Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, The Celts: A History, Boydell Press, 2002, ISBN 0-85115-923-0, p. 153

- Integratio: Dobrogea de Nord: Isaccea: History Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, a project of the Centro Universitario Europeo per i Beni Culturali, accessed December 2006.

- Constantin Haită. "Studiu sedimentologic preliminar pe situl neolitic Isaccea-Suhat. Campania 1998", Peuce (ISSN 0258-8102), 2003, 14, p.447-452.

- Alexandru Barnea, "Noviodunum, azi Isaccea (I)", Ziarul Financiar, August 17, 2007

- D.M. Pippidi et al., (1976) Dicționar de istorie veche a României, Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică (OCLC 251847977), p 431-432; entry: Noviodunum

- "Archeological research on Noviodunum". Archived from the original on 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

- Bărbulescu et al., p. 73

- J. J. Wilkes, "The Roman Danube: An Archaeological Survey", The Journal of Roman Studies, ISSN 0075-4358, Vol. 95, 2005, p.217

- Bărbulescu et al., p. 57

- Bărbulescu et al., p. 60

- D.M. Pippidi et al., (1976) Dicționar de istorie veche a României, Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică (OCLC 251847977), p 185; entry: Constantinus

- Mircea Păcurariu, "Sfinți daco-romani și români", Editura Mitropoliei Moldovei și Bucovinei, Iași, 1994, ISBN 973-96208-6-8, p.25

- Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic Wars, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-84633-2. p.116

- Ammianus Marcellinus, The Later Roman Empire, AD 354-378, translated by Walter Hamilton (Penguin ISBN 0-14-044406-8), book 15

- E. A. Thompson, The Huns, Blackwell Publishing, 1999, ISBN 978-0-631-21443-4, p.269-270

- Bărbulescu et al., p. 103

- Jordanes, The Origins and Deeds of the Goths, translated by Charles C. Mierow, V. 35

- Kiel, p. 288

- "Observaţii asupra revoltei din Paradunavon din 1072-1091" Archived 2009-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, in Istorie și ideologie. Editura Universității din București, 2002, ISBN 973-575-658-7, p.34-46.

- Paul Stephenson, Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-77017-3, p. 86

- Stephenson, p.103

- Curta, p.302

- Curta, p.319-320

- Stănciugel et al. p. 45

- Kiel, p. 289

- Stănciugel et al. p. 55

- Vasary, p.90

- Vasary, p.89-90

- Colin Imber, The Crusade of Varna, 1443-45, 2006, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-0144-7 p. 4-5

- David Turnock, The Making of Eastern Europe, Taylor & Francis, 1988, ISBN 0-415-01267-8, p. 138

- Kurt W. Treptow, Dracula: Essays on the Life and Times of Vlad Țepeș, Columbia University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-88033-220-4

- Radu R. Florescu, Raymond McNally, Dracula: Prince of many faces - His life and his times, Back Bay Books, 1990, ISBN 0-316-28656-7, p. 134

- according to the Ottoman tahrir defterleri (tax registers) of 1528, 1569/1570 and 1597/1598; in Kiel, p. 289

- Kiel, p. 289-290

- Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit, 1865

- Nicolae Iorga, Studiĭ istorice asupra Chilieĭ și Cetățiĭ-Albe, Institutul de arte grafice C. Göbl, 1900, p.217

- Kiel, p. 291

- Ileana Căzan, Eugen Denize, Marile puteri şi spaţiul românesc în secolele XV-XVI Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, Editura Universității din București, 2001, ISBN 973-575-597-1, p. 276

- (in Romanian) Valentin Gheonea, "Dumitraşcu Cantacuzino - Un fanariot pe tronul Moldovei în secolul XVII Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine", Magazin Istoric (ISSN 0541-881X), December 1997

- John, P. LeDonne, The Grand Strategy of the Russian Empire, 1650-1831 Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-516100-9, p. 40

- (in Russian) Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона), I.A. Efron, 1906, vol. 13, Page 364; Isakcha(Исакча)

- "The Seat of War on the Danube," The Times, December 29, page 8

- James J. Reid, Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839-1878, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2000, ISBN 3-515-07687-5 p. 317

- Keith Hitchins, Rumania : 1866-1947 (Oxford History of Modern Europe). 1994. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822126-6, p. 47-48

- Glenn Torrey, "Indifference and Mistrust: Russian-Romanian Collaboration in the Campaign of 1916", The Journal of Military History, Vol. 57, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 284, 288

- "Russians still retire in Dobrudja", New York Times, December 25, 1916, pg. 3

- Treaty of Bucharest, 7 May 1918 Archived 23 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, article X

- (in French) Convention d’armistice du 11 novembre 1918 (wikisource)

- Hill, Cameron (February 27, 2022). "Romania: Thousands of Ukrainians arrive to Isaccea in search of refuge". Euronews. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- Recensământul Populaţiei 2011

- Kiel, 294

- (in French) Nicoară Beldiceanu; Jean-Louis Bacque-Grammont; Matei Cazacu, Recherches sur les Ottomans et la Moldavie ponto-danubienne entre 1484 et 1520, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (ISSN 0041-977X), Vol. 45, No. 1. (1982), pp. 55.

- Biroul Electoral Central, Primari pe municipii, oraşe şi comune

- (in Romanian) Claudia Petraru, "Tulcenii au votat schimbarea. Trei primari de oraşe au fost înlocuiţi" Archived 2012-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, Adevărul, June 11, 2012

- "Results of the 2016 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Stănciugel et al. p. 138

- Isaccea city hall - Economic data Archived 2008-08-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fabrica de caviar" Archived 2009-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, România Liberă, February 19, 2007

- "Economie: Infrastructura" Archived 2008-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, Primăria Orașului Isaccea

- "Proiectul Nabucco promite afaceri uriaşe pentru firmele româneşti", Capital, July 9, 2008

- "De la ruşi vine curentul ieftin!", Adevărul, July 16, 2007

- "Oraşele Măcin şi Isaccea vor avea primele staţii de epurare din 2012", Bursa, January 12, 2009

References

- (in Romanian) Eugen Panighiant, Delta Dunării și Razelmul, Bucharest, 1960

- István Vásáry, Cumans and Tatars, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-511-11015-4

- (in Romanian) Robert Stănciugel and Liliana Monica Bălașa, Dobrogea în Secolele VII-XIX. Evoluție istorică, Bucharest, 2005

- Curta, Florin, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-81539-8

- (in Romanian) Bărbulescu; Hitchins; Papacostea; Teodor; Deletant et al., Istoria Românilor, ed. Institutul de Istorie Nicolae Iorga, 1998, ISBN 973-45-0244-1

- Machiel Kiel, "Ottoman Urban Development and the cult of a Heterodox Sufi Saint: Sarı Saltuk Dede and towns of Isakçe and Babadagin the Northern Dobrudja" in Gilles Veinstein, "Syncrétismes Et Hérésies Dans L'Orient Seljoukide Et Ottoman (XIVe-XVIIIe Siècles): Actes Du Colloque Du Collège de France, Octobre 2001", Peeters Publishers, 2005, ISBN 90-429-1549-8

External links

- Isaccea: Official site

- Noviodunum Archaeological Project Archived 2010-09-07 at the Wayback Machine Archaeological project being run on the outskirts of the town.

- STRATEG. Defensive strategies and cross border policies. Integration of the Lower Danube area in the Roman civilization Archived 2020-10-25 at the Wayback Machine