Nubra

Nubra, also called Dumra, is a historical region of Ladakh, India[1] that is currently administered as a subdivision and a tehsil in the Leh district. Its inhabited areas form a tri-armed valley cut by the Nubra and Shyok rivers. Its Tibetan name Dumra means "valley of flowers".[2] Demands have been raised and BJP has hinted at creation of Nubra as a new district.[3] Diskit, the headquarters of Nubra, is 120 km north of Leh, the capital of Ladakh.

Nubra | |

|---|---|

region | |

Nubra Valley with Diskit Gompa and town immediately below and Hunder in the distance | |

Nubra Location in Ladakh, India  Nubra Nubra (India) | |

| Coordinates: 34.6°N 77.7°E | |

| Country | |

| Union Territory | Ladakh |

| District | Leh |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

The Shyok River meets the Nubra River (or Siachan River) to form a large valley that separates the Ladakh and Karakoram Ranges. The Shyok river is a tributary of the Indus river. The average altitude of the valley is more than 10,000 feet (3,000 m) above the sea level. The most common way to access this valley is to travel over the Khardung La pass from Leh.

Foreign nationals are required to get a Protected area permit to visit Nubra. Since 1 April 2017 Indian citizens are also required to get an Inner Line Permit to visit it.[4]

Name

Nubra (Tibetan: ནུབ་ར, Wylie: nub ra, THL: nup ra) means "western" in Ladakhi, thus referring to the "western valley", perhaps distinguishing it from the thinly-populated eastern Shyok river valley. The traditional name of the region is Dumra (Tibetan: ལྡུམ་ར, Wylie: ldum ra, THL: dum ra), meaning "valley of flowers".[2]

Geography

Alexander Cunningham listed Nubra as one of the five natural and historical divisions of Ladakh.[5] Nubra occupies the northeastern portion of Ladakh, bordering Baltistan and Chinese Turkestan in the north, and the Aksai Chin plateau and Tibet in the east. In Cunningham's conception, Nubra includes all the region drained by the Nubra and Shyok rivers. it is 128 miles long and 72 miles wide, making up an area of 9,200 square miles. It extends south till the Pangong Lake.[6]

In modern nomenclature, the Nubra region is divided into "Diskit Nubra" in the north and the "Darbuk region" in the south, both of which are regarded as tehsils and subdivisions of the Leh district.[7] The Diskit Nubra region includes the Turtuk block populated by Balti people, which became a part of Indian-administered Kashmir after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, and the unpopulated Siachen Glacier region.[8]

The populated part of Nubra is often described as a "tri-armed valley",[9] the three arms being:[10]

- the Nubra River Valley (divided into three sections called Yarma, Tśurka and Farka),[lower-alpha 1]

- Gyen, the upper Shyok valley from its southern bend till the confluence with the Nubra River, and

- Shama, the lower Shyok valley from the confluence till the Chorbat area.[10]

The eastern Shyok valley is mostly unpopulated, even though it has numerous camping sites that have been used by trade caravans. Murgo is a village on the tributary called Murgo Nala.

Topography

Like the rest of the Tibetan Plateau, Nubra is a high altitude cold desert with rare precipitation and scant vegetation except along river beds. The villages are irrigated and fertile, producing wheat, barley, peas, mustard and a variety of fruits and nuts, including blood apples, walnuts, apricots and even a few almond trees. Most of Nubra is inhabited by Nubra dialect or Nubra Skat speakers. The majority are Buddhists. In the western or lowest altitude end of Nubra near the Line of Control i.e. the Indo-Pak border, along the Shyok River, the inhabitants of Turtuk are Balti of Gilgit-Baltistan, who speak Balti, and are Shia and Sufia Nurbakhshia Muslims.

Siachen Glacier lies to the north of the valley. The Sasser Pass and the famous Karakoram Pass lie to the northwest of the valley and connect Nubra with Uyghur (Mandarin : Xinjiang). Previously much trade passed through the area towards western China's Xinjiang and Central Asia. The people of Baltistan also used the Nubra valley for passage to Tibet.[11]

Places

Diskit town in the valley have become the congregation centre for people of the region. Diskit is the headquarters of Nubra and thus has lot of government offices with basic facilities. It is also connected by road with Leh.

Along the Nubra or Siachan River lie the villages of Sumur, Kyagar (called Tiger Hill by the Indian Army), Tirith, Panamik, Turtuk and many others.

Travel routes

.jpg.webp)

The main road access to Nubra is over Khardung La which is open throughout the year. The highest elevation of Khardung La is 5,359 m (17,582 ft), its status as the highest motorable road in the world is no longer accepted by most authorities.[12] An alternative route, opened in 2008, crosses the Wari La from Sakti, to the east of Khardung La, connecting to the main Nubra road system via Agham and Khalsar along the Shyok River. There are also trekkable passes over the Ladakh Range from the Indus Valley at various points. Routes from Nubra to Baltistan and Yarkand, though historically important, have been closed since 1947 and 1950 respectively.

Tourism

The Nubra valley was open for tourists up to Hunder (the land of sand dunes) until 2010. The region beyond Hunder gives way to a greener region of Ladakh because of its lower altitude. The village of Turtuk which was unseen by tourists till 2010 is a virgin destination for people who seek peace and an interaction with a tribal community of Ladakh. The local Balti people follow their age old customs in their lifestyle and speak a language which oral and not yet written. For tourists Turtuk offers serene camping sites with environment friendly infrastructure.

Panamik is noted for its hot springs. Between Hundar and Diskit lie seven kilometres of sand dunes, and (two-humped) Bactrian camels graze in the neighbouring "forests" of seabuckthorn. Non-locals are not allowed below Hundar village into the Balti area, as it is a border area.

Monasteries

The 32-metre Maitreya Buddha statue is the landmark of Nubra and is maintained by the Diskit Monastery. On the Shyok River, the main village, Diskit, is home to the dramatically positioned Diskit Monastery which was built in 14th century. Hundar was the capital of the erstwhile Nubra kingdom in the 17th century, and is home to the Chamba Gompa.

Samstanling Monastery is between Kyagar and Sumoor villages. Across the Nubra or Siachan River at Panamik, is the isolated Ensa Gompa.

Yarma Gompa, between Saser and Siachen Base Camp, is one of the large monastery belonging to the Drukpa Kagyu lineage and it manages the following village gompas, Tong-sted, Nyung-sted, Dungsa, Khemi, Tsang-lung-ka, Sarsoma, Aarunuk, Ayi, Kovet, Tangsa & Murgo. The senior to lower hierarchy of gompa administration is Lopon, Gye-nyen, Geylong, Gye-tsul, and cun-zung.[13]

Flora and fauna

The valley is famous for its forest of Hippophae shrub, popularly known as Leh Berry. It is within this shrub forest that one can spot the white-browed tit-warbler. One can also spot the Tibetan lark, Hume's short-toed lark, and Hume's whitethroat. The various water birds like ruddy shelduck, garganey, northern pintail, and mallard can be observed on several small water bodies scattered along the route. Besides these, waders like black-tailed godwit, common sandpiper, common greenshank, common redshank, green sandpiper, and ruff can be spotted in Nubra.[14]

Education

The valley has been secluded as has been most of the exterior parts of Ladakh. Almost all of the region has been facing problems to get good quality education. There have been initiatives in the past by the government but extreme weather conditions and vicinity to the borders have been a major hurdle in implementing a solid education base. There is also migration of the population that gets exposed to the big cities of India and hence the people do not get benefitted out of their local learned population. There are very few Non-Government organizations active in Nubra region.

In popular culture

Nubra valley was appeared, mentioned in Hollywood movie Mission Impossible : Fallout of Tom Cruise. In the film's climax Ethan Hunt (Cruise) stop Walker (Henry Cavill) from detonating Plutonium bomb at the base of Siachen glacier . However filming of the scene was done in New Zealand due to India government denied filming.[15]

Gallery

Nubra valley sandunes

Nubra valley sandunes

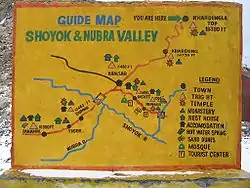

Local map with North towards down

Local map with North towards down View from Diskit gompa on Nubra Valley

View from Diskit gompa on Nubra Valley Seabuckthorn berries, Nubra valley, Ladakh

Seabuckthorn berries, Nubra valley, Ladakh Bactrian camels

Bactrian camels Nubra Valley

Nubra Valley This is enroute town called Hunder in Nubra.

This is enroute town called Hunder in Nubra. Nubra Valley with Diskit Gompa and town immediately below and Hunder in the distance

Nubra Valley with Diskit Gompa and town immediately below and Hunder in the distance Hunder, Nubra Valley

Hunder, Nubra Valley Tent Resort in Nubra Valley

Tent Resort in Nubra Valley

See also

- Ladakh

- Khardung La

- Siachen Glacier

- Thoise

- Chalunka

- Project HIMANK, road builders in the valley and creators of curious sign boards

- Disket

Notes

- Yarma is the upper part of the valley above Panamik, Tsurka is the right bank of the valley below Panamik, while Yarma is the left bank.

References

- Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons (2009), pp. 583–584: "The Tibetan soldiers pursued the remaining troops as far as a place called Dumra,[10: These days, Dumra is called Nupra] just one day’s journey from Leh, where the Tibetan army pitched their camp."

- Kapadia, Harish (1999). Across Peaks & Passes in Ladakh, Zanskar & East Karakoram. Indus Publishing. p. 230. ISBN 978-81-7387-100-9.

- 3,000 Demonstrate for Separate District in Sub-Zero Temperatures at Kargil, The Wire, 06/FEB/2020.

- People, Attractions & Transportation in Nubra Valley, The Off: Leh Ladakh XP (Jai Kishan), 17 March 2021.

- Cunningham, Ladak (1854), p. 18: "The natural divisions of the country are: 1st, Nubra on the Shayok; 2nd, Ladak Proper, on the Indus; 3rd, Zanskar, on the Zanskar river; 4th, Rukchu [Rupshu], around the lakes of Tshomo Riri [Tso Moriri] and Tsho-Kar; 5th, Purik, Suru, and Dras, on the different branches of the Dras river; 6th, Spiti, on the Spiti river: and 7th, Lahul, on the Chandra and Bhaga, or head-waters of the Chenab. These also are the actual divisions of the country, for the natural boundaries of a mountainous district generally remain unaltered, in spite of the changes wrought by war and religion. Ladak is divided politically between Maharaja Gulab Sing and the East-India Company. To the former belong all the northern districts, to the latter only the two southern districts of Lahul and Spiti."

- Cunningham, Ladak (1854), p. 21.

- Tehsil, Leh district administration, retrieved 15 November 2020.

- Muhammad Raafi, Interview of Delan Namgial, Kashmiri Life, 17 January 2017.

- Sumedha Das, Paradise on Earth, The Statesman, 24 November 2019.

- Vohra, Mythic Lore from Nubra Valley (1990), pp. 225–226.

- Senge H. Sering, “Reclaiming Nubra” – Locals Shunning Pakistani Influences Archived 8 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, Delhi, 17 August 2009.

- "Nubra Valley - World's Finest Wool". www.worlds-finest-wool.com. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- Prem Singh Jina, 2009, Cultural Heritage of Ladakh Himalaya, p 114.

- Khan, Asif (2016). "Ladakh: The Land Beyond". Buceros. 21 (3): 6–15.

- "Tom Cruise's MI..." Hindustan Times.

Bibliography

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854), Ladak: Physical, Statistical, Historical, London: Wm. H. Allen and Co – via archive.org

- Francke, Rev. A. H. (1907), A History of Western Tibet, S. W. Partridge & Co – via archive.org

- Longstaff, T. G. (June 1910), "Glacier Exploration in the Eastern Karakoram", The Geographical Journal, The Royal Geographical Society, 35 (6): 622–653, doi:10.2307/1777235, JSTOR 1777235

- Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (2009), One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-17732-1

- Shakspo, Nawang Tsering (1999), "The Foremost Teachers of the Kings of Ladakh", in Martijn van Beek; Kristoffer Brix Bertelsen; Poul Pedersen (eds.), Recent Research on Ladakh 8, Aarhus University Press, pp. 284–, ISBN 978-87-7288-791-3

- Thomson, Thomas (1852), Western Himalaya and Tibet: A Narrative of a Journey Through the Mountains of Northern India, During the Years 1847-8, Reeve and Company – via archive.org

- Vohra, Rohit (1990), "Mythic Lore and Historical Documents from Nubra Valley in Ladakh", Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Akadémiai Kiadó, 44 (1/2): 225–239, JSTOR 23658122