Ancient Egyptian mathematics

Ancient Egyptian mathematics is the mathematics that was developed and used in Ancient Egypt c. 3000 to c. 300 BCE, from the Old Kingdom of Egypt until roughly the beginning of Hellenistic Egypt. The ancient Egyptians utilized a numeral system for counting and solving written mathematical problems, often involving multiplication and fractions. Evidence for Egyptian mathematics is limited to a scarce amount of surviving sources written on papyrus. From these texts it is known that ancient Egyptians understood concepts of geometry, such as determining the surface area and volume of three-dimensional shapes useful for architectural engineering, and algebra, such as the false position method and quadratic equations.

Overview

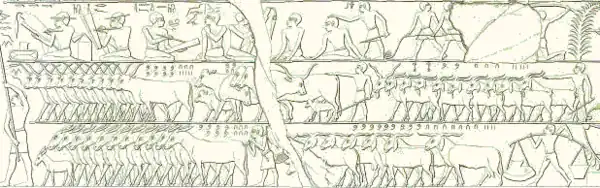

Written evidence of the use of mathematics dates back to at least 3200 BC with the ivory labels found in Tomb U-j at Abydos. These labels appear to have been used as tags for grave goods and some are inscribed with numbers.[1] Further evidence of the use of the base 10 number system can be found on the Narmer Macehead which depicts offerings of 400,000 oxen, 1,422,000 goats and 120,000 prisoners.[2] Archaeological evidence has suggested that the Ancient Egyptian counting system had origins in Sub-Saharan Africa.[3] Also, fractal geometry designs which are widespread among Sub-Saharan African cultures are also found in Egyptian architecture and cosmological signs.[4]

The evidence of the use of mathematics in the Old Kingdom (c. 2690–2180 BC) is scarce, but can be deduced from inscriptions on a wall near a mastaba in Meidum which gives guidelines for the slope of the mastaba.[5] The lines in the diagram are spaced at a distance of one cubit and show the use of that unit of measurement.[1]

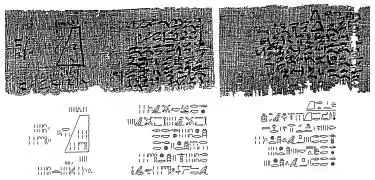

The earliest true mathematical documents date to the 12th Dynasty (c. 1990–1800 BC). The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, the Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll, the Lahun Mathematical Papyri which are a part of the much larger collection of Kahun Papyri and the Berlin Papyrus 6619 all date to this period. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus which dates to the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650 BC) is said to be based on an older mathematical text from the 12th dynasty.[6]

The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus and Rhind Mathematical Papyrus are so called mathematical problem texts. They consist of a collection of problems with solutions. These texts may have been written by a teacher or a student engaged in solving typical mathematics problems.[1]

An interesting feature of ancient Egyptian mathematics is the use of unit fractions.[7] The Egyptians used some special notation for fractions such as 1/2, 1/3 and 2/3 and in some texts for 3/4, but other fractions were all written as unit fractions of the form 1/n or sums of such unit fractions. Scribes used tables to help them work with these fractions. The Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll for instance is a table of unit fractions which are expressed as sums of other unit fractions. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and some of the other texts contain 2/n tables. These tables allowed the scribes to rewrite any fraction of the form 1/n as a sum of unit fractions.[1]

During the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC) mathematical problems are mentioned in the literary Papyrus Anastasi I, and the Papyrus Wilbour from the time of Ramesses III records land measurements. In the workers village of Deir el-Medina several ostraca have been found that record volumes of dirt removed while quarrying the tombs.[1][6]

Sources

Current understanding of ancient Egyptian mathematics is impeded by the paucity of available sources. The sources that do exist include the following texts (which are generally dated to the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period):

- The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus[8]

- The Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll[8]

- The Lahun Mathematical Papyri[8]

- The Berlin Papyrus 6619, written around 1800 BC

- The Akhmim Wooden Tablet[6]

- The Reisner Papyrus, dated to the early Twelfth dynasty of Egypt and found in Nag el-Deir, the ancient town of Thinis[8]

- The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (RMP), dated from the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650 BC), but its author, Ahmes, identifies it as a copy of a now lost Middle Kingdom papyrus. The RMP is the largest mathematical text.[8]

From the New Kingdom there are a handful of mathematical texts and inscriptions related to computations:

- The Papyrus Anastasi I, a literary text written as a (fictional) letter written by a scribe named Hori and addressed to a scribe named Amenemope. A segment of the letter describes several mathematical problems.[6]

- Ostracon Senmut 153, a text written in hieratic[6]

- Ostracon Turin 57170, a text written in hieratic[6]

- Ostraca from Deir el-Medina contain computations. Ostracon IFAO 1206 for instance shows the calculation of volumes, presumably related to the quarrying of a tomb.[6]

Numerals

Ancient Egyptian texts could be written in either hieroglyphs or in hieratic. In either representation the number system was always given in base 10. The number 1 was depicted by a simple stroke, the number 2 was represented by two strokes, etc. The numbers 10, 100, 1000, 10,000 and 100,000 had their own hieroglyphs. Number 10 is a hobble for cattle, number 100 is represented by a coiled rope, the number 1000 is represented by a lotus flower, the number 10,000 is represented by a finger, the number 100,000 is represented by a frog, and a million was represented by a god with his hands raised in adoration.[8]

| 1 | 10 | 100 | 1000 | 10,000 | 100,000 | 1,000,000 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Egyptian numerals date back to the Predynastic period. Ivory labels from Abydos record the use of this number system. It is also common to see the numerals in offering scenes to indicate the number of items offered. The king's daughter Neferetiabet is shown with an offering of 1000 oxen, bread, beer, etc.

The Egyptian number system was additive. Large numbers were represented by collections of the glyphs and the value was obtained by simply adding the individual numbers together.

The Egyptians almost exclusively used fractions of the form 1/n. One notable exception is the fraction 2/3, which is frequently found in the mathematical texts. Very rarely a special glyph was used to denote 3/4. The fraction 1/2 was represented by a glyph that may have depicted a piece of linen folded in two. The fraction 2/3 was represented by the glyph for a mouth with 2 (different sized) strokes. The rest of the fractions were always represented by a mouth super-imposed over a number.[8]

| 1/2 | 1/3 | 2/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Notation

Steps of calculations were written in sentences in Egyptian languages. (e.g. "Multiply 10 times 100; it becomes 1000.")

In Rhind Papyrus Problem 28, the hieroglyphs

|

(D54, D55), symbols for feet, were used to mean "to add" and "to subtract." These were presumably shorthands for

|

Multiplication and division

Egyptian multiplication was done by a repeated doubling of the number to be multiplied (the multiplicand), and choosing which of the doublings to add together (essentially a form of binary arithmetic), a method that links to the Old Kingdom. The multiplicand was written next to figure 1; the multiplicand was then added to itself, and the result written next to the number 2. The process was continued until the doublings gave a number greater than half of the multiplier. Then the doubled numbers (1, 2, etc.) would be repeatedly subtracted from the multiplier to select which of the results of the existing calculations should be added together to create the answer.[2]

As a shortcut for larger numbers, the multiplicand can also be immediately multiplied by 10, 100, 1000, 10000, etc.

For example, Problem 69 on the Rhind Papyrus (RMP) provides the following illustration, as if Hieroglyphic symbols were used (rather than the RMP's actual hieratic script).[8]

| To multiply 80 × 14 | ||||||||||

| Egyptian calculation | Modern calculation | |||||||||

| Result | Multiplier | Result | Multiplier | |||||||

| 80 | 1 | |||||||||

| 800 | 10 | |||||||||

| 160 | 2 | |||||||||

| 320 | 4 | |||||||||

| 1120 | 14 | |||||||||

The ![]() denotes the intermediate results that are added together to produce the final answer.

denotes the intermediate results that are added together to produce the final answer.

The table above can also be used to divide 1120 by 80. We would solve this problem by finding the quotient (80) as the sum of those multipliers of 80 that add up to 1120. In this example that would yield a quotient of 10 + 4 = 14.[8] A more complicated example of the division algorithm is provided by Problem 66. A total of 3200 ro of fat are to be distributed evenly over 365 days.

| 1 | 365 | |

| 2 | 730 | |

| 4 | 1460 | |

| 8 | 2920 | |

| 2/3 | 243+1/3 | |

| 1/10 | 36+1/2 | |

| 1/2190 | 1/6 |

First the scribe would double 365 repeatedly until the largest possible multiple of 365 is reached, which is smaller than 3200. In this case 8 times 365 is 2920 and further addition of multiples of 365 would clearly give a value greater than 3200. Next it is noted that 2/3 + 1/10 + 1/2190 times 365 gives us the value of 280 we need. Hence we find that 3200 divided by 365 must equal 8 + 2/3 + 1/10 + 1/2190.[8]

Algebra

Egyptian algebra problems appear in both the Rhind mathematical papyrus and the Moscow mathematical papyrus as well as several other sources.[8]

| Aha in hieroglyphs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | |||

Aha problems involve finding unknown quantities (referred to as Aha) if the sum of the quantity and part(s) of it are given. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus also contains four of these type of problems. Problems 1, 19, and 25 of the Moscow Papyrus are Aha problems. For instance problem 19 asks one to calculate a quantity taken 1+1/2 times and added to 4 to make 10.[8] In other words, in modern mathematical notation we are asked to solve the linear equation:

Solving these Aha problems involves a technique called method of false position. The technique is also called the method of false assumption. The scribe would substitute an initial guess of the answer into the problem. The solution using the false assumption would be proportional to the actual answer, and the scribe would find the answer by using this ratio.[8]

The mathematical writings show that the scribes used (least) common multiples to turn problems with fractions into problems using integers. In this connection red auxiliary numbers are written next to the fractions.[8]

The use of the Horus eye fractions shows some (rudimentary) knowledge of geometrical progression. Knowledge of arithmetic progressions is also evident from the mathematical sources.[8]

Quadratic equations

The ancient Egyptians were the first civilization to develop and solve second-degree (quadratic) equations. This information is found in the Berlin Papyrus fragment. Additionally, the Egyptians solve first-degree algebraic equations found in Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.[11]

Geometry

There are only a limited number of problems from ancient Egypt that concern geometry. Geometric problems appear in both the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus (MMP) and in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (RMP). The examples demonstrate that the Ancient Egyptians knew how to compute areas of several geometric shapes and the volumes of cylinders and pyramids.

- Area:

- Triangles: The scribes record problems computing the area of a triangle (RMP and MMP).[8]

- Rectangles: Problems regarding the area of a rectangular plot of land appear in the RMP and the MMP.[8] A similar problem appears in the Lahun Mathematical Papyri in London.[12][13]

- Circles: Problem 48 of the RMP compares the area of a circle (approximated by an octagon) and its circumscribing square. This problem's result is used in problem 50, where the scribe finds the area of a round field of diameter 9 khet.[8]

- Hemisphere: Problem 10 in the MMP finds the area of a hemisphere.[8]

- Volumes:

- Cylindrical (cylinder): Several problems compute the volume of cylindrical granaries (RMP 41–43), while problem 60 RMP seems to concern a pillar or a cone instead of a pyramid. It is rather small and steep, with a seked (reciprocal of slope) of four palms (per cubit).[8] In section IV.3 of the Lahun Mathematical Papyri the volume of a granary with a circular base is found using the same procedure as RMP 43.

- Rectangular (Cuboid): Several problems in the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus (problem 14) and in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (numbers 44, 45, 46) compute the volume of a rectangular granary.[12]

- Truncated pyramid (frustum) Frustum: The volume of a truncated pyramid is computed in MMP 14.[8]

The Seqed

Problem 56 of the RMP indicates an understanding of the idea of geometric similarity. This problem discusses the ratio run/rise, also known as the seqed. Such a formula would be needed for building pyramids. In the next problem (Problem 57), the height of a pyramid is calculated from the base length and the seked (Egyptian for the reciprocal of the slope), while problem 58 gives the length of the base and the height and uses these measurements to compute the seqed. In Problem 59 part 1 computes the seqed, while the second part may be a computation to check the answer: If you construct a pyramid with base side 12 [cubits] and with a seqed of 5 palms 1 finger; what is its altitude?[8]

See also

References

- Imhausen, Annette (2006). "Ancient Egyptian Mathematics: New Perspectives on Old Sources". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 28 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1007/bf02986998. S2CID 122060653.

- Burton, David (2005). The History of Mathematics: An Introduction. McGraw–Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-305189-5.

- Eglash, Ron (1999). African fractals : modern computing and indigenous design. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 89, 141. ISBN 0813526140.

- Eglash, R. (1995). "Fractal Geometry in African Material Culture". Symmetry: Culture and Science. 6–1: 174–177.

- Rossi, Corinna (2007). Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69053-9.

- Katz V, Imhasen A, Robson E, Dauben JW, Plofker K, Berggren JL (2007). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- Reimer, David (2014-05-11). Count Like an Egyptian: A Hands-on Introduction to Ancient Mathematics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400851416.

- Clagett, Marshall Ancient Egyptian Science, A Source Book. Volume Three: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics (Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society) American Philosophical Society. 1999 ISBN 978-0-87169-232-0

- Chace, Arnold Buffum; Bull, Ludlow; Manning, Henry Parker (1929). The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. Vol. 2. Mathematical Association of America.

- Cajori, Florian (1993) [1929]. A History of Mathematical Notations. Dover Publications. pp. pp. 229–230. ISBN 0-486-67766-4.

- Moore, Deborah Lela (1994). The African roots of mathematics (2nd ed.). Detroit, Mich.: Professional Educational Services. ISBN 1884123007.

- R.C. Archibald Mathematics before the Greeks Science, New Series, Vol.73, No. 1831, (Jan. 31, 1930), pp. 109–121

- Annette Imhausen Digitalegypt website: Lahun Papyrus IV.3

Further reading

- Boyer, Carl B. 1968. History of Mathematics. John Wiley. Reprint Princeton U. Press (1985).

- Chace, Arnold Buffum. 1927–1929. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: Free Translation and Commentary with Selected Photographs, Translations, Transliterations and Literal Translations. 2 vols. Classics in Mathematics Education 8. Oberlin: Mathematical Association of America. (Reprinted Reston: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1979). ISBN 0-87353-133-7

- Clagett, Marshall. 1999. Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book. Volume 3: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society 232. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-232-5

- Couchoud, Sylvia. 1993. Mathématiques égyptiennes: Recherches sur les connaissances mathématiques de l'Égypte pharaonique. Paris: Éditions Le Léopard d'Or

- Daressy, G. "Ostraca," Cairo Museo des Antiquities Egyptiennes Catalogue General Ostraca hieraques, vol 1901, number 25001-25385.

- Gillings, Richard J. 1972. Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs. MIT Press. (Dover reprints available).

- Imhausen, Annette. 2003. "Ägyptische Algorithmen". Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz

- Johnson, G., Sriraman, B., Saltztstein. 2012. "Where are the plans? A socio-critical and architectural survey of early Egyptian mathematics"| In Bharath Sriraman, Editor. Crossroads in the History of Mathematics and Mathematics Education. The Montana Mathematics Enthusiast Monographs in Mathematics Education 12, Information Age Publishing, Inc., Charlotte, NC

- Neugebauer, Otto (1969) [1957]. The Exact Sciences in Antiquity (2 ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22332-2. PMID 14884919.

- Peet, Thomas Eric. 1923. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, British Museum 10057 and 10058. London: The University Press of Liverpool limited and Hodder & Stoughton limited

- Reimer, David (2014). Count Like an Egyptian: A Hands-on Introduction to Ancient Mathematics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16012-2.

- Robins, R. Gay. 1995. "Mathematics, Astronomy, and Calendars in Pharaonic Egypt". In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, edited by Jack M. Sasson, John R. Baines, Gary Beckman, and Karen S. Rubinson. Vol. 3 of 4 vols. New York: Charles Schribner's Sons. (Reprinted Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2000). 1799–1813

- Robins, R. Gay, and Charles C. D. Shute. 1987. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus: An Ancient Egyptian Text. London: British Museum Publications Limited. ISBN 0-7141-0944-4

- Sarton, George. 1927. Introduction to the History of Science, Vol 1. Willians & Williams.

- Strudwick, Nigel G., and Ronald J. Leprohon. 2005. Texts from the Pyramid Age. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13048-9.

- Struve, Vasilij Vasil'evič, and Boris Aleksandrovič Turaev. 1930. Mathematischer Papyrus des Staatlichen Museums der Schönen Künste in Moskau. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik; Abteilung A: Quellen 1. Berlin: J. Springer

- Van der Waerden, B.L. 1961. Science Awakening". Oxford University Press.

- Vymazalova, Hana. 2002. Wooden Tablets from Cairo...., Archiv Orientální, Vol 1, pages 27–42.

- Wirsching, Armin. 2009. Die Pyramiden von Giza – Mathematik in Stein gebaut. (2 ed) Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-8370-2355-8.