Nuralagus

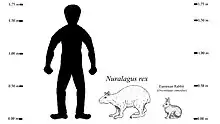

Nuralagus is an extinct genus of leporid (the family of rabbits and hares), with a single species, Nuralagus rex, described in 2011. It lived on Menorca, one of the Balearic Islands in the western Mediterranean during the Pliocene epoch. It is the largest known lagomorph to have ever existed, with an estimated weight of 8–12 kilograms (18–26 lb), nearly double the weight of the average Flemish Giant rabbit. It likely went extinct at the Pliocene-Pleistocene transition when Mallorca and Menorca were united as one island, letting the mammalian fauna of Mallorca, including the goat-like ungulate Myotragus, colonize Nuralagus's habitat.

| Nuralagus Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Genus: | †Nuralagus Quintana et al., 2011 |

| Species: | †N. rex |

| Binomial name | |

| †Nuralagus rex Quintana et al., 2011 | |

Discovery

So far, all of the fossils have been found in fissure fill deposits in the northwest of Menorca, dating to sometime in the Pliocene. The material was originally preliminarily described by Pons-Moya et al. in 1981, who referred it to cf. Alilepus. The genus and species Nuralagus rex were described in 2011 in a full description of the material, which included the front half of a skull, as well as numerous isolated postcranial bones corresponding to most of the skeleton.[1]

Description

With a height of half a meter and an estimated weight of 12 kg (26 lb),[1][2] or 8 kg (18 lb)[3] the species is the largest known lagomorph, being ten times the weight of the average wild European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and around double the weight of the average Flemish Giant rabbit. Its size was likely due to island gigantism. It had a comparatively small skull relative to its body size and small sensory receptors, including orbits and tympanic bullae, suggesting reduced senses of hearing and eyesight.[1] Nuralagus rex had a short and stiff spine which resulted in low mobility and an inability to jump like other leporids.[4] Bone histology analysis suggests that the species was sexually dimorphic, with females being larger than males. The growth lines within the bones suggest that the large body size was the result of growing over a longer period of time, rather than the result of increasing growth rates. The age of sexual maturity was estimated at 3.6 years for females and 6.2 years for males, considerably higher than would be expected solely based on bodymass.[5]

Evolution

Nuralagus rex likely entered what is now Menorca during the Messinian Salinity Crisis 5.96-5.3 million years ago. During this event, the Strait of Gibraltar closed, leading to the desiccation of the Mediterranean Sea, resulting in the connection of the islands to the Iberian Peninsula, letting Nuralagus's ancestor colonize the area. The subsequent Zanclean flood 5.3 million years ago then returned the Mediterranean to its original sea levels, isolating Nuralagus's ancestor on Menorca.[6] There is a dearth of knowledge about the evolutionary history of Nuralagus rex in relation to other lagomorphs. However, similarities between the dental morphology of Nuralagus and Eurasian members of the extinct genus Alilepus have led to speculation that Alilepus is closely related to and, possibly, the ancestor of Nuralagus.[1][7] The only other mammal native to Menorca during the Pliocene was the extinct giant dormouse species Muscardinus cyclopeus, which belongs to the same genus as the living hazel dormouse, with a herpetofauna including the giant tortoise Solitudo gymnesica, snakes, amphisbaenian, lacertid and gekkonid lizards, and alytid frogs.[8] Nuralagus probably became extinct around the end of the Pliocene and the beginning of the Pleistocene, corresponding with the colonisation of Menorca by the mammals that lived on Mallorca (comprising the goat-antelope Myotragus, the shrew Nesiotites and the dormouse Hypnomys) due to the islands being connected during low sea level episodes as a result of Quaternary glaciation.[9][10]

Nuralagus's unique traits were most likely the product of an insular environment containing no natural predators. Physical similarities between Nuralagus rex and Pentalagus furnessi (an extant insular lagomorph which until recently also did not have natural predators) despite the phylogenetic and geographical distance between the two species further supports this inference.[1]

References

- Quintana, Josep; Kohler, Mike; Moya-Sola, Salvador (2011). "Nuralagus rex, gen. et sp. nov., an endemic insular giant rabbit from the Neogene of Minorca". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 231–240. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.550367. S2CID 83649921.

- Susan Milius (2011). "The Bunny That Ruled Minorca". Science News. 179 (9): 18. doi:10.1002/scin.5591790921.

- Moncunill‐Solé, B.; Quintana, J.; Jordana, X.; Engelbrektsson, P.; Köhler, M. (April 2015). "The weight of fossil leporids and ochotonids: body mass estimation models for the order Lagomorpha". Journal of Zoology. 295 (4): 269–278. doi:10.1111/jzo.12209. ISSN 0952-8369.

- Kohler, Meike (7 April 2011). "Palaeontology: The giant rabbits of Minorca". Nature. 472 (7341): 9. Bibcode:2011Natur.472S...9.. doi:10.1038/472009c.

- Köhler, Meike; Nacarino-Meneses, Carmen; Cardona, Josep Quintana; Arnold, Walter; Stalder, Gabrielle; Suchentrunk, Franz; Moyà-Solà, Salvador (September 2023). "Insular giant leporid matured later than predicted by scaling". iScience. 26 (9): 107654. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.107654. PMC 10485033. PMID 37694152.

- Jennifer Vegas (March 21, 2011). "Biggest-ever bunny didn't hop, had no enemies". Discovery News. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- Naish, Darren. "You have your giant fossil rabbit neck all wrong". Scientific American. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Bover, Pere; Rofes, Juan; Bailon, Salvador; Agustí, Jordi; Cuenca-Bescós, Gloria; Torres, Enric; Alcover, Josep Antoni (March 2014). "Late Miocene/Early Pliocene vertebrate fauna from Mallorca (Balearic Islands, Western Mediterranean): an update". Integrative Zoology. 9 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12049. hdl:10261/113378.

- PALOMBO, Maria Rita (January 2018). "Insular mammalian fauna dynamics and paleogeography: A lesson from the Western Mediterranean islands". Integrative Zoology. 13 (1): 2–20. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12275. ISSN 1749-4877. PMC 5817236. PMID 28688123.

- Cardona, Josep Quintana; Agusti, Jordi (May 2019). "First evidence of faunal succession in terrestrial vertebrates of the Plio-Pleistocene of the Balearic Islands, western Mediterranean". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 18 (3): 317–324. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2019.02.001.