Nursehound

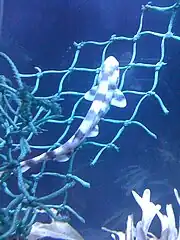

The nursehound (Scyliorhinus stellaris), also known as the large-spotted dogfish, greater spotted dogfish or bull huss, is a species of catshark, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae, found in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. It is generally found among rocks or algae at a depth of 20–60 m (66–197 ft). Growing up to 1.6 m (5.2 ft) long, the nursehound has a robust body with a broad, rounded head and two dorsal fins placed far back. It shares its range with the more common and closely related small-spotted catshark (S. canicula), which it resembles in appearance but can be distinguished from, in having larger spots and nasal skin flaps that do not extend to the mouth.

| Nursehound | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Scyliorhinidae |

| Genus: | Scyliorhinus |

| Species: | S. stellaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Scyliorhinus stellaris | |

| |

| Range of the nursehoundV | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Scyllium acanthonotum* De Filippi, 1857 * ambiguous synonym | |

Nursehounds have nocturnal habits and generally hide inside small holes during the day, often associating with other members of its species. A benthic predator, it feeds on a range of bony fishes, smaller sharks, crustaceans, and cephalopods. Like other catsharks, the nursehound is oviparous in reproduction. Females deposit large, thick-walled egg cases, two at a time, from March to October, securing them to bunches of seaweed. The eggs take 7–12 months to hatch. Nursehounds are marketed as food in several European countries under various names, including "flake", "catfish", "rock eel", and "rock salmon". It was once also valued for its rough skin (called "rubskin"), which was used as an abrasive. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the nursehound as Vulnerable, as its population in the Mediterranean Sea seems to have declined substantially from overfishing.

Taxonomy

The first scientific description of the nursehound was published by Carl Linnaeus, in the 1758 tenth edition of Systema Naturae. He gave it the name Squalus stellaris, the specific epithet stellaris being Latin for "starry". No type specimen was designated. In 1973, Stewart Springer moved this species to the genus Scyliorhinus.[2][3] The common name "nursehound" came from an old belief by English fishermen that this shark attends to its smaller relatives, while the name "huss" may have come from a distortion of the word "nurse" over time.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The nursehound is found in the northeastern Atlantic from southern Norway and Sweden to Senegal, including off the British Isles, throughout the Mediterranean Sea, and the Canary Islands. It may occur as far south as the mouth of the Congo River, though these West African records may represent misidentifications of the West African catshark (S. cervigoni).[5] Its range seems to be rather patchy, particularly around offshore islands, where there are small local populations with limited exchange between them.[1] The nursehound can be found from the intertidal zone to a depth of 400 m (1,300 ft), though it is most common between 20 m (66 ft) and 60–125 m (197–410 ft).[1] This bottom-dwelling species prefers quiet water over rough or rocky terrain, including sites with algal cover. In the Mediterranean, it favors algae-covered coral.[2][6]

Description

The nursehound attains a length of 1.6 m (5.2 ft), though most measure less than 1.3 m (4.3 ft).[2] This shark has a broad, rounded head and a stout body that tapers towards the tail. The eyes are oval in shape, with a thick fold of skin on the lower rim but no nictitating membrane. Unlike in the small-spotted catshark, the large flaps of skin beside the nares do not reach the mouth.[6] In the upper jaw, there are 22–27 tooth rows on either side and 0–2 teeth at the symphysis (center); in the lower jaw, there are 18–21 tooth rows on either side and 2–4 teeth at the symphysis. The teeth are Y-shaped and smooth-edged; the anterior teeth have a single central cusp, while the posterior teeth have an additional pair of lateral cusplets. Towards the rear of the jaws, the teeth become progressively smaller and more angled, with proportionately larger lateral cusplets.[7] The five pairs of gill slits are small, with the last two over the pectoral fin bases.[6]

The two dorsal fins are placed far back on the body; the first is larger than the second and originates over the bases of the pelvic fins. The pectoral fins are large. In males, the inner margins of the pelvic fins are merged into an "apron" over the claspers. The caudal fin is broad and nearly horizontal, with an indistinct lower lobe. The skin is very rough, due to a covering of large, upright dermal denticles.[2] The nursehound has small black dots covering its back and sides, interspersed with brown spots of varying shapes larger than the pupil, on a grayish or brownish background. The pattern is highly variable across individuals and ages; there may also be white spots, or the brown spots may be expanded so that almost the whole body is dark, or a series of faint "saddles" may be present. The underside is plain white.[5][6]

Biology and ecology

Primarily nocturnal, nursehounds spend the day inside small holes in rocks and swim into deeper water at night to hunt. Sometimes two sharks will squeeze into the same hole, and several individuals will seek out refuges within the same local area. In one tracking study, a single immature nursehound was observed to use five different refuges in succession over a period of 168 days, consistently returning to each one over a number of days before moving on. Nursehounds may occupy refuges to hide from predators, avoid harassment by mature conspecifics, and/or to facilitate thermoregulation.[8] In captivity, these sharks are gregarious and tend to rest in groups, though the individuals comprising any particular group changes frequently.[9] This species is less common than the small-spotted catshark.[6]

The nursehound feeds on a variety of benthic organisms, including bony fishes such as mackerel, deepwater cardinalfishes, dragonets, gurnards, flatfishes, and herring, and smaller sharks such as the small-spotted catshark. It also consumes crustaceans, in particular crabs but also hermit crabs and large shrimp, and cephalopods.[2][10] Given the opportunity, this shark will scavenge.[6] Adults consume relatively more bony fish and cephalopods, and fewer crustaceans, than juveniles.[1] Known parasites of this species include the monogeneans Hexabothrium appendiculatum and Leptocotyle major,[11][12] the tapeworm Acanthobothrium coronatum,[13] the trypanosome Trypanosoma scyllii,[14] the isopod Ceratothoa oxyrrhynchaena,[15] and the copepod Lernaeopoda galei.[16] The netted dog whelk (Nassarius reticulatus) preys on the nursehound's eggs by piercing the case and extracting the yolk.[17]

Life history

Like other members of its family, the nursehound is oviparous. Known breeding grounds include the River Fal estuary and Wembury Bay in England,[17] and a number of coastal sites around the Italian Peninsula, in particular the Santa Croce Bank in the Gulf of Naples.[18] Adults move into shallow water in the spring or early summer, and mate only at night.[19] The eggs are deposited in the shallows from March to October.[10] Although a single female produces 77–109 oocytes per year, not all of these are ovulated and estimates of the actual number of eggs laid range from 9 to 41.[19] The eggs mature and are released two at a time, one from each oviduct.[2] Each egg is enclosed in a thick, dark brown case measuring 10–13 cm (3.9–5.1 in) long and 3.5 cm (1.4 in) wide. There are tendrils at the four corners, that allow the female to secure the egg cases to bunches of seaweed (usually Cystoseira spp. or Laminaria saccharina).[17]

Eggs in the North Sea and the Atlantic take 10–12 months to hatch, while those from the southern Mediterranean take 7 months to hatch. The length at hatching is 16 cm (6.3 in) off Britain, and 10–12 cm (3.9–4.7 in) off France. Newly hatched sharks grow at a rate of 0.45–0.56 mm (0.018–0.022 in) per day, and have prominent saddle markings. Sexual maturity is attained at a length of 77–79 cm (30–31 in), which corresponds to an age of four years if hatchling growth rates remain constant.[10][19] This species has a lifespan of at least 19 years.[20]

Human interactions

Nursehounds are generally harmless to humans.[21] However, 19th-century British naturalist Jonathan Couch noted that "although not so formidable with its teeth as many other sharks, this fish is well able to defend itself from an enemy. When seized it throws its body round the arm that holds it, and by a contractile and reversed action of its body grates over the surface of its enemy with the rugged spines of its skin, like a rasp. There are few animals that can bear so severe an infliction, by which their surface is torn with lacerated wounds."[22] This shark is displayed by many public aquariums and has been bred in captivity.[9]

The rough skin (called "rubskin") of the nursehound was once used to polish wood and alabaster, to smooth arrows and barrels, and to raise the hairs of beaver hats as a replacement for pumice. Rubskin was so valued that a pound of it was worth a hundredweight of sandpaper.[23][24] The liver was also used as a source of oil, and the carcasses cut up and used to bait crab traps.[23] The meat of this species is marketed fresh or dried and salted, though it is considered "coarse" in some quarters.[21][23] In the United Kingdom, it is one of the species sold under the names "flake", "catfish", "huss" "rock eel" or "rock salmon".[4][25] In France, it is sold as grande roussette or saumonette, as after being skinned and beheaded it resembles salmon.[26] This species is also sometimes processed into fishmeal, or its fins dried and exported to the Asian market. In European waters, commercial production of this species is led by France, followed by the UK and Portugal; it is caught using bottom trawls, gillnets, bottom set longlines, handlines and fixed bottom nets. In 2004, a total catch of 208 tons was reported from the northeastern Atlantic.[1][2][27]

The impact of fishing activities on the nursehound is difficult to assess as species-specific data is generally lacking. This species is more susceptible to overfishing than the small-spotted catshark because of its larger size and fragmented distribution, which limits the recovery potential of depleted local stocks. There is evidence that its numbers have declined significantly in the Gulf of Lion, off Albania, and around the Balearic Islands.[1] In the upper Tyrrhenian Sea, its numbers have fallen by over 99% since the 1970s.[28] These declines have led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to list the nursehound as Vulnerable.[1]

References

- Finucci, B.; Derrick, D.; Pacoureau, N. (2021). "Scyliorhinus stellaris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T161484A124493465. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T161484A124493465.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 366–367. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- Squalus stellaris. (2007). Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved on July 24, 2009.

- Davidson, A. (2002). Mediterranean Seafood: A Comprehensive Guide with Recipes (third ed.). Ten Speed Press. p. 28. ISBN 1-58008-451-6.

- Compagno, L.J.V.; Dando, M. & Fowler, S. (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- Lythgoe, J. & Lythgoe, G. (1992). Fishes of the Sea: The North Atlantic and Mediterranean. MIT Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-262-12162-X.

- Soldo, A.; Dulcic, J. & Cetinic, P. (2000). "Contribution to the study of the morphology of the teeth of the nursehound Scyliorhinus stellaris (Chondrichthyes: Scyliorhinidae)". Scientia Marina. 64 (3): 355–356. doi:10.3989/scimar.2000.64n3355.

- Sims, D.W.; Southall, E.J.; Wearmouth, V.J.; Hutchinson, N.; Budd, G.C. & Morritt, D. (2005). "Refuging behaviour in the nursehound Scyliorhinus stellaris (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii): preliminary evidence from acoustic telemetry". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 85 (5): 1137–1140. doi:10.1017/S0025315405012191. S2CID 55023417.

- Scott, G.W.; Gibbs, K. & Holding, J. (1997). "Group 'resting' behaviour in a population of captive bull huss (Scyliorhinus stellaris)". Aquarium Sciences and Conservation. 1 (4): 251–254. doi:10.1023/A:1018364424195. S2CID 81406286.

- Ford, E. (1921). "A contribution to our knowledge of the life-histories of the dogfishes landed at Plymouth" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 12 (3): 468–505. doi:10.1017/S0025315400006317. S2CID 86685874.

- Kearn, G.C. (2004). Leeches, Lice and Lampreys: A Natural History of Skin and Gill Parasites of Fishes. Springer. p. 104. ISBN 1-4020-2925-X.

- Llewellyn, J.; Green, J.E. & Kearn, G.C. (1984). "A check-list of monogenean (Platyhelminth) parasites of Plymouth hosts". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 64 (4): 881–887. doi:10.1017/S0025315400047299. S2CID 86795527.

- Williams, H.H. & Jones, A. (1994). Parasitic Worms of Fish. CRC Press. p. 336. ISBN 0-85066-425-X.

- Pulsford, A. (1983). "Preliminary studies on trypanospmes from the dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula L". Journal of Fish Biology. 24 (6): 671–682. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1984.tb04838.x.

- Ramdane, Z.; Bensouilah, M.A. & Trilles, J.P. (2007). "The Cymothoidae (Crustacea, Isopoda), parasites on marine fishes, from Algerian fauna". Belgian Journal of Zoology. 137 (1): 67–74.

- Karaytug, S.; Sak, S. & Alper, A. (2004). "Parasitic Copepod Lernaeopoda galei Krøyer, 1837 (Copepoda: Siphonostomatoida): A First Record from Turkish Seas". Turkish Journal of Zoology. 28: 123–128.

- Orton, J.H. (1926). "A Breeding Ground of the Nursehound (Scyliorhinus stellaris) in the Fal Estuary". Nature. 118 (2977): 732. Bibcode:1926Natur.118..732O. doi:10.1038/118732a0. S2CID 4163315.

- de Sabata, S.; Clò, S. (2013). "Some breeding sites of the nursehound (Scyiorhinus stellaris) in Italian waters as reported by divers" (PDF). Biologia Marina Mediterranea. 20 (1): 178–179.

- Capapé, C.; Vergne, Y.; Vianet, R.; Guélorget, O. & Quignard, J. (2006). "Biological observations on the nursehound, Scyliorhinus stellaris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Chondrichthyes: Scyliorhinidae) in captivity". Acta Adriatica. 47 (1): 29–36.

- Longevity, ageing, and life history of Scyliorhinus stellaris. AnAge: The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved on July 17, 2009.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2009). "Scyliorhinus stellaris" in FishBase. July 2009 version.

- Couch, J. (1868). A History of the Fishes of the British Islands. Groombridge and Sons. p. 11–12.

- Day, F. (1884). "The Fishes of Great Britain and Ireland". Williams and Norgate: 312–313.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Yaxley, D. (2003). A Researcher's Glossary of Words Found in Historical Documents of East Anglia. Larks Press. p. 107. ISBN 1-904006-13-2.

- Davidson, A. (2004). North Atlantic Seafood: A Comprehensive Guide with Recipes (third ed.). Ten Speed Press. p. 168. ISBN 1-58008-450-8.

- Vannuccini, S. (1999). Shark Utilization, Marketing and Trade. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. pp. 175–176. ISBN 92-5-104361-2.

- FAO Yearbook [of] Fishery Statistics: Aquaculture Production, 2004. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2006. p. 436. ISBN 92-5-005519-6.

- Ferretti, F., Myers, R.A., Sartor, P. and Serena, F. (2005). Long Term Dynamics of the Chondrichthyan Fish Community in the Upper Tyrrhenian Sea. ICES Council Meeting, 2005/N:25. Retrieved on July 15, 2009.

External links

Media related to Scyliorhinus stellaris at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Scyliorhinus stellaris at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Scyliorhinus stellaris at Wikispecies

Data related to Scyliorhinus stellaris at Wikispecies- Photos of Nursehound on Sealife Collection