Old South Meeting House

The Old South Meeting House is a historic Congregational church building located at the corner of Milk and Washington Streets in the Downtown Crossing area of Boston, Massachusetts, built in 1729. It gained fame as the organizing point for the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. Five thousand or more colonists[2] gathered at the Meeting House, the largest building in Boston at the time.

Old South Meeting House | |

The Old South Meeting House, 1968 | |

| |

| Location | Corner of Washington and Milk Streets Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°21′25″N 71°3′31″W |

| Built | 1729 |

| Architect | Twelves, Robert |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000778[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | October 9, 1960 |

History

Church (1729–1872)

The meeting house or church was completed in 1729, with its 56 m (183 ft) steeple. The congregation was gathered in 1669 when it broke off from First Church of Boston, a Congregational church founded by John Winthrop in 1630. The site was a gift of Mrs. Norton, widow of John Norton, pastor of the First Church in Boston.[3] The church's first pastor was Rev. Thomas Thacher, a native of Salisbury, England. Thacher was also a physician and is known for publishing the first medical tract in Massachusetts.

After the Boston Massacre in 1770, yearly anniversary meetings were held at the church until 1775, featuring speakers such as John Hancock and Dr. Joseph Warren. In 1773, 5,000 people met in the Meeting House to debate British taxation and, after the meeting, a group raided three tea ships anchored nearby in what became known as the Boston Tea Party.

In October 1775, led by Lt Col Samuel Birch of the 17th Dragoons, the British occupied the Meeting House due to its association with the Revolutionary cause. They gutted the building, filled it with dirt, and then used the interior to practice horse riding. They destroyed much of the interior and stole various items, including William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation (1620), a unique Pilgrim manuscript hidden in Old South's tower. After the British evacuated Boston, the plan for rebuilding the interior of the church was drawn by Thomas Dawes.[4]

Old South Meeting House was almost destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872. As the fire approached the historic structure, Boston firefighting crews, understanding the importance of the building to the history of Boston and the nation, staged a massive effort to protect it. Aided by the arrival of fire companies from across New England, the firefighters took heroic measures to extinguish the flames after a twelve-hour battle, saving Old South and stopping the fire before it reached other historic buildings and residential neighborhoods. As the city rebuilt, the congregation sought out a quieter neighborhood, away from the bustling commercial area near OSMH. The congregation built a new church building (the "New" Old South Church in the Back Bay, at Copley Square), which remains its home to this day. In 1877, a group of twenty women, including the philanthropist Mary Hemenway (who used $100,000 of her own funds), raised money and helped pass legislation to preserve and save the Meeting House. By 1910, preservation work was transferred to the Old South Association through aid from the Mary Hemenway Foundation. The Old South congregation returns to Old South Meeting House for services in its ancestral home once a year, on the Sunday before Thanksgiving.

.jpg.webp)

Ministers

- Thomas Thacher (1620–1678), minister 1670–1678[5]

- Samuel Willard (1640–1707), minister 1678–1707[6]

- Ebenezer Pemberton (1671–1717), minister 1700–1717[7]

- Joseph Sewall (1688–1769), minister 1713–1769[8]

- Thomas Prince (1687–1758), minister 1718–1758[9]

- Alexander Cumming (1726–1763), minister 1761–1763[10]

- Samuel Blair (1741–1818), minister 1766-1769[11][12]

- John Bacon (b.1737), minister 1772–1775[13]

- Joseph Eckley (1750–1811), minister 1779–1811[14]

- Joshua Huntington (1786–1819), minister 1808–1819[15]

- Benjamin B. Wisner (1794–1835), minister 1821–1832[16]

- Samuel H. Stearns (1801–1837), minister 1834–1836[17][18]

- George W. Blagden (1802–1884), minister 1836–1872[19][20]

- Jacob M. Manning (1824–1882), minister 1857–1872[21]

Notable congregants

- John Alden

- John Alden Jr.

- Judith Quincy Hull

- Hannah Quincy Hull (Sewall)

- John Hull

- Daniel Quincy

- Samuel Adams

- William Dawes

- Benjamin Franklin

- Samuel Sewall

- Phillis Wheatley

Museum (1877–present)

Old South Meeting House has been an important gathering place for nearly three centuries. Renowned for the protest meetings held here before the American Revolution when the building was termed a mouth-house, this National Historic Landmark has long served as a platform for the free expression of ideas. Today, the Old South Meeting House is open daily as a museum and continues to provide a place for people to meet, discuss and act on important issues of the day. The stories of the men and women who are part of Old South's vital heritage reveal why the Old South Meeting House occupies an enduring place in the history of the United States.

The museum and historic site is located at the intersection of Washington and Milk Streets and can be visited for a nominal sum. It is located near the State Street, Downtown Crossing and Park Street MBTA (subway) stations.

The Old South Meeting House is claimed to be the second oldest establishment existent in the United States. It is currently under consideration for local landmark status by the Boston Landmarks Commission.[22]

In 2020 the former caretaker of Old South Meeting House (the Old South Association in Boston) merged with the Bostonian Society, forming Revolutionary Spaces, which now manages both Old South Meeting House and the Old State House.[23]

Gallery

Joseph Sewall, minister ca.1713–1769

Joseph Sewall, minister ca.1713–1769 Thomas Prince, minister ca.1718–1758; portrait by Joseph Badger (courtesy American Antiquarian Society)

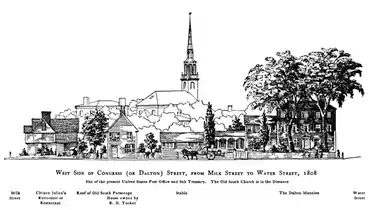

Thomas Prince, minister ca.1718–1758; portrait by Joseph Badger (courtesy American Antiquarian Society) View of Old South from Congress Street in 1808 (conjectural illustration)

View of Old South from Congress Street in 1808 (conjectural illustration) 1835

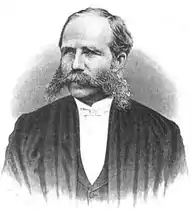

1835 Jacob Manning, minister ca.1857–1872

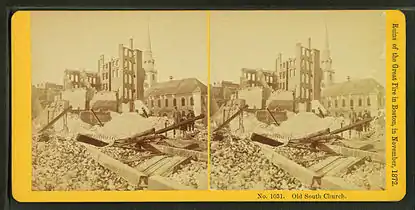

Jacob Manning, minister ca.1857–1872 After the fire (Old South at left), 1872

After the fire (Old South at left), 1872 After the fire, 1872

After the fire, 1872 Old South Meeting House, ca. 1877

Old South Meeting House, ca. 1877 ca.1898

ca.1898.jpg.webp) Washington & Milk St., 1900

Washington & Milk St., 1900

See also

References

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- John Galvin puts that number as high as 8,000 (Three Men of Boston, New York: Thomas Cromwell, 1976, p. 268).

- Bridgeman, Thomas (1856). The Pilgrims of Boston and their Descendants. New York: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 54–58. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- Eckley, Joseph. "Obituary: Sketch of the Character of the Late Hon. Thomas Dawes, Esq.," 1809, Boston Athenaeum Library, Tracts B438, B1213.

- WorldCat. Thacher, Thomas 1620-1678

- WorldCat. Willard, Samuel 1640-1707

- WorldCat. Pemberton, Ebenezer 1672-1717

- WorldCat. Sewall, Joseph 1688-1769

- WorldCat. Prince, Thomas 1687-1758

- WorldCat. Cumming, A. (Alexander) 1726-1763

- Cyclopaedia of Biblical, theological, and ecclesiastical literature. 1894

- Weis, Frederick Lewis. Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania 1628-1776 (PDF). American Antiquarian Society.

- New England historical & genealogical register, v.26. 1872

- WorldCat. Eckley, Joseph 1750-1811

- WorldCat. Huntington, Joshua 1786-1819

- WorldCat. Wisner, Benjamin B. (Benjamin Blydenburg) 1794-1835

- WorldCat. Stearns, Samuel H. (Samuel Horatio) 1801-1837

- Bowen's picture of Boston, 3rd ed. 1888.

- WorldCat. Blagden, George W. (George Washington) 1802-1884

- "Boston Pulpit". Gleasons Pictorial. Boston, Mass. 5. 1853.

- WorldCat. Manning, Jacob M. (Jacob Merrill) 1824-1882

- https://www.cityofboston.gov/images_documents/PETSTATS_June2016_tcm3-53570.pdf

- "News & Press". Revolutionary Spaces. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

Further reading

- B. Wisner. History of the Old South Church in Boston: in four sermons. 1830.

- Hamilton Andrews Hill. History of the Old South Church (Third Church) Boston: 1669–1884. v.1 + v.2. Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1889.

External links

- The Old South Meeting House

- Old South Church in Boston (the congregation formerly located at the Meeting House)

- Boston National Historical Park Official Website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress). Old South Meetinghouse, Washington & Milk Streets, Boston, Suffolk, MA

- The Diaries of John Hull, Mint-master and Treasurer of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay