Old Trafford

Old Trafford (/ˈtræfərd/) is a football stadium in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England, and the home of Manchester United. With a capacity of 74,310[1] it is the largest club football stadium (and second-largest football stadium overall after Wembley Stadium) in the United Kingdom, and the twelfth-largest in Europe.[3] It is about 0.5 miles (800 m) from Old Trafford Cricket Ground and the adjacent tram stop.

"The Theatre of Dreams" | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | Sir Matt Busby Way Old Trafford Trafford Greater Manchester England |

|---|---|

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Manchester United |

| Operator | Manchester United |

| Capacity | 74,310[1] |

| Record attendance | 76,962 (Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Grimsby Town, 25 March 1939) |

| Field size | 105 by 68 metres (114.8 yd × 74.4 yd)[2] |

| Surface | Desso GrassMaster |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1909 |

| Opened | 19 February 1910 |

| Renovated | 1941, 1946–1949, 1951, 1957, 1973, 1995–1996, 2000, 2006 |

| Construction cost | £90,000 (1909) |

| Architect | Archibald Leitch (1909) |

| Tenants | |

| Manchester United F.C. (1910–present) | |

Nicknamed "The Theatre of Dreams" by Bobby Charlton,[4] Old Trafford has been United's home ground since 1910, although from 1941 to 1949 the club shared Maine Road with local rivals Manchester City as a result of Second World War bomb damage. Old Trafford underwent several expansions in the 1990s and 2000s, including the addition of extra tiers to the North, West and East Stands, almost returning the stadium to its original capacity of 80,000. Future expansion is likely to involve the addition of a second tier to the South Stand, which would raise the capacity to around 88,000. The stadium's record attendance was recorded in 1939, when 76,962 spectators watched the FA Cup semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Grimsby Town.

Old Trafford has hosted an FA Cup Final, two final replays and was regularly used as a neutral venue for the competition's semi-finals. It has also hosted England fixtures, matches at the 1966 World Cup, Euro 96 and the 2012 Summer Olympics, including women's international football for the first time in its history, and the 2003 Champions League Final. Outside football, it has been the venue for rugby league's annual Super League Grand Final every year except 2020, and the final of Rugby League World Cups in 2000, 2013 and 2022.

History

Construction and early years

Before 1902, Manchester United were known as Newton Heath, during which time they first played their football matches at North Road and then Bank Street in Clayton. However, both grounds were blighted by wretched conditions, the pitches ranging from gravel to marsh, while Bank Street suffered from clouds of fumes from its neighbouring factories.[5] Therefore, following the club's rescue from near-bankruptcy and renaming, the new chairman John Henry Davies decided in 1909 that the Bank Street ground was not fit for a team that had recently won the First Division and FA Cup, so he donated funds for the construction of a new stadium.[6] Not one to spend money frivolously, Davies scouted around Manchester for an appropriate site, before settling on a patch of land adjacent to the Bridgewater Canal, just off the north end of the Warwick Road in Old Trafford.[7]

Designed by Scottish architect Archibald Leitch, who designed several other stadia, the ground was originally designed with a capacity of 100,000 spectators and featured seating in the south stand under cover, while the remaining three stands were left as terraces and uncovered.[8] Including the purchase of the land, the construction of the stadium was originally to have cost £60,000 all told. However, as costs began to rise, to reach the intended capacity would have cost an extra £30,000 over the original estimate and, at the suggestion of club secretary J. J. Bentley, the capacity was reduced to approximately 80,000.[9][10] Nevertheless, at a time when transfer fees were still around the £1,000 mark, the cost of construction only served to reinforce the club's "Moneybags United" epithet, with which they had been tarred since Davies had taken over as chairman.[11]

In May 1908, Archibald Leitch wrote to the Cheshire Lines Committee (CLC) – who had a rail depot adjacent to the proposed site for the football ground – in an attempt to persuade them to subsidise construction of the grandstand alongside the railway line. The subsidy would have come to the sum of £10,000, to be paid back at the rate of £2,000 per annum for five years or half of the gate receipts for the grandstand each year until the loan was repaid. However, despite guarantees for the loan coming from the club itself and two local breweries, both chaired by club chairman John Henry Davies, the Cheshire Lines Committee turned the proposal down.[12] The CLC had planned to build a new station adjacent to the new stadium, with the promise of an anticipated £2,750 per annum in fares offsetting the £9,800 cost of building the station. The station – Trafford Park – was eventually built, but further down the line than originally planned.[7] The CLC later constructed a modest station with one timber-built platform immediately adjacent to the stadium and this opened on 21 August 1935. It was initially named United Football Ground,[13] but was renamed Old Trafford Football Ground in early 1936. It was served on match days only by a shuttle service of steam trains from Manchester Central railway station.[14] It is currently known as Manchester United Football Ground.[15]

Construction was carried out by Messrs Brameld and Smith of Manchester[16] and development was completed in late 1909. The stadium hosted its inaugural game on 19 February 1910, with United playing host to Liverpool. However, the home side were unable to provide their fans with a win to mark the occasion, as Liverpool won 4–3. A journalist at the game reported the stadium as "the most handsomest [sic], the most spacious and the most remarkable arena I have ever seen. As a football ground it is unrivalled in the world, it is an honour to Manchester and the home of a team who can do wonders when they are so disposed".[17]

Before the construction of Wembley Stadium in 1923, the FA Cup Final was hosted by a number of different grounds around England including Old Trafford.[18] The first of these was the 1911 FA Cup Final replay between Bradford City and Newcastle United, after the original tie at Crystal Palace finished as a no-score draw after extra time. Bradford won 1–0, the goal scored by Jimmy Speirs, in a match watched by 58,000 people.[19] The ground's second FA Cup Final was the 1915 final between Sheffield United and Chelsea. Sheffield United won the match 3–0 in front of nearly 50,000 spectators, most of whom were in the military, leading to the final being nicknamed "the Khaki Cup Final".[20] On 27 December 1920, Old Trafford played host to its largest pre-Second World War attendance for a United league match, as 70,504 spectators watched the Red Devils lose 3–1 to Aston Villa.[21] The ground hosted its first international football match later that decade, when England lost 1–0 to Scotland in front of 49,429 spectators on 17 April 1926.[22][23] Unusually, the record attendance at Old Trafford is not for a Manchester United home game. Instead, on 25 March 1939, 76,962 people watched an FA Cup semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Grimsby Town.[24]

Wartime bombing

_1992.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In 1936, as part of a £35,000 refurbishment, an 80-yard-long roof was added to the United Road stand (now the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand) for the first time,[25] while roofs were added to the south corners in 1938.[26] Upon the outbreak of the Second World War, Old Trafford was requisitioned by the military to be used as a depot.[27] Football continued to be played at the stadium, but a German bombing raid on Trafford Park on 22 December 1940 damaged the stadium to the extent that a Christmas day fixture against Stockport County had to be switched to Stockport's ground.[27] Football resumed at Old Trafford on 8 March 1941, but another German raid on 11 March 1941 destroyed much of the stadium, notably the main stand (now the South Stand), forcing the club's operations to move to Cornbrook Cold Storage, owned by United chairman James W. Gibson.[27] After pressure from Gibson, the War Damage Commission granted Manchester United £4,800 to remove the debris and £17,478 to rebuild the stands.[25] During the reconstruction of the stadium, Manchester United played their "home" games at Maine Road, the home of their cross-town rivals, Manchester City, at a cost of £5,000 a year plus a percentage of the gate receipts.[28] The club was now £15,000 in debt, not helped by the rental of Maine Road, and the Labour MP for Stoke, Ellis Smith, petitioned the Government to increase the club's compensation package, but it was in vain.[25] Though Old Trafford was reopened, albeit without cover, in 1949, it meant that a league game had not been played at the stadium for nearly 10 years.[29] United's first game back at Old Trafford was played on 24 August 1949, as 41,748 spectators witnessed a 3–0 victory over Bolton Wanderers.[30]

Completion of the master plan

A roof was restored to the Main Stand by 1951 and, soon after, the three remaining stands were covered, the operation culminating with the addition of a roof to the Stretford End (now the West Stand) in 1959.[26] The club also invested £40,000 in the installation of proper floodlighting, so that they would be able to use the stadium for the European games that were played in the late evening of weekdays, instead of having to play at Maine Road. In order to avoid obtrusive shadows being cast on the pitch, two sections of the Main Stand roof were cut away.[25] The first match to be played under floodlights at Old Trafford was a First Division match between Manchester United and Bolton Wanderers on 25 March 1957.[16]

However, although the spectators would now be able to see the players at night, they still suffered from the problem of obstructed views caused by the pillars that supported the roofs. With the 1966 FIFA World Cup fast approaching, at which the stadium would host three group matches, this prompted the United directors to completely redesign the United Road (north) stand. The old roof pillars were replaced in 1965 with modern-style cantilevering on top of the roof, allowing every spectator a completely unobstructed view,[26] while it was also expanded to hold 20,000 spectators (10,000 seated and 10,000 standing in front) at a cost of £350,000.[31] The architects of the new stand, Mather and Nutter (now Atherden Fuller),[16] rearranged the organisation of the stand to have terracing at the front, a larger seated area towards the back, and the first private boxes at a British football ground. The east stand – the only remaining uncovered stand – was developed in the same style in 1973.[32] With the first two stands converted to cantilevers, the club's owners devised a long-term plan to do the same to the other two stands and convert the stadium into a bowl-like arena.[33] Such an undertaking would serve to increase the atmosphere within the ground by containing the crowd's noise and focusing it onto the pitch, where the players would feel the full effects of a capacity crowd.[34] Meanwhile, the stadium hosted its third FA Cup Final, hosting 62,078 spectators for the replay of the 1970 final between Chelsea and Leeds United; Chelsea won the match 2–1. The ground also hosted the second leg of the 1968 Intercontinental Cup, which saw Estudiantes de La Plata win the cup after a 1–1 draw.[35] The 1970s saw the dramatic rise of football hooliganism in Britain,[36] and a knife-throwing incident in 1971 forced the club to erect the country's first perimeter fence, restricting fans from the Old Trafford pitch.[31]

Conversion to all-seater

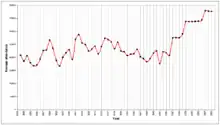

With every subsequent improvement made to the ground since the Second World War, the capacity steadily declined. By the 1980s, the capacity had dropped from the original 80,000 to approximately 60,000. The capacity dropped still further in 1990, when the Taylor Report recommended, and the government demanded that all First and Second Division stadia be converted to all-seaters. This meant that £3–5 million plans to replace the Stretford End with a brand new stand with an all-standing terrace at the front and a cantilever roof to link with the rest of the ground had to be drastically altered.[16] This forced redevelopment, including the removal of the terraces at the front of the other three stands, not only increased the cost to around £10 million, but also reduced the capacity of Old Trafford to an all-time low of around 44,000.[37] In addition, the club was told in 1992 that they would only receive £1.4 million of a possible £2 million from the Football Trust to be put towards work related to the Taylor Report.[38]

.JPG.webp)

The club's resurgence in success and increase in popularity in the early 1990s ensured that further development would have to occur. In 1995, the 30-year-old North Stand was demolished and work quickly began on a new stand,[39] to be ready in time for Old Trafford to host three group games, a quarter-final and a semi-final at Euro 96. The club purchased the Trafford Park trading estate, a 20-acre (81,000 m2) site on the other site of United Road, for £9.2 million in March 1995. Construction began in June 1995 and was completed by May 1996, with the first two of the three phases of the stand opening during the season. Designed by Atherden Fuller, with Hilstone Laurie as project and construction managers and Campbell Reith Hill as structural engineers, the new three-tiered stand cost a total of £18.65 million to build and had a capacity of about 25,500, raising the capacity of the entire ground to more than 55,000. The cantilever roof would also be the largest in Europe, measuring 58.5 m (192 ft) from the back wall to the front edge.[40] Further success over the next few years guaranteed yet more development. First, a second tier was added to the East Stand. Opened in January 2000, the stadium's capacity was temporarily increased to about 61,000 until the opening of the West Stand's second tier, which added yet another 7,000 seats, bringing the capacity to 68,217. It was now not only the biggest club stadium in England but the biggest in all of the United Kingdom.[41] Old Trafford hosted its first major European final three years later, playing host to the 2003 UEFA Champions League Final between Milan and Juventus.[42]

From 2001 to 2007, following the demolition of the old Wembley Stadium, the England national football team was forced to play its games elsewhere. During that time, the team toured the country, playing their matches at various grounds from Villa Park in Birmingham to St James' Park in Newcastle. From 2003 to 2007, Old Trafford hosted 12 of England's 23 home matches, more than any other stadium. The latest international to be held at Old Trafford was England's 1–0 loss to Spain on 7 February 2007.[43] The match was played in front of a crowd of 58,207.[44]

2006 expansion

Old Trafford's most recent expansion, which took place between July 2005 and May 2006, saw an increase of around 8,000 seats with the addition of second tiers to both the north-west and north-east quadrants of the ground.[33] Part of the new seating was used for the first time on 26 March 2006, when an attendance of 69,070 became a new Premier League record.[45] The record continued to be pushed upwards before reaching its current peak on 31 March 2007, when 76,098 spectators saw United beat Blackburn Rovers 4–1, meaning that just 114 seats (0.15% of the total capacity of 76,212) were left unoccupied.[46] In 2009, a reorganisation of the seating in the stadium resulted in a reduction of the capacity by 255 to 75,957, meaning that the club's home attendance record would stand at least until the next expansion.[47][48]

Old Trafford celebrated its 100th anniversary on 19 February 2010. In recognition of the occasion, Manchester United's official website ran a feature in which a memorable moment from the stadium's history was highlighted on each of the 100 days leading up to the anniversary.[49] From these 100 moments, the top 10 were chosen by a panel including club statistician Cliff Butler, journalist David Meek, and former players Pat Crerand and Wilf McGuinness.[50] At Old Trafford itself, an art competition was run for pupils from three local schools to create their own depictions of the stadium in the past, present and future.[51] Winning paintings were put on permanent display on the concourse of the Old Trafford family stand, and the winners were presented with awards by artist Harold Riley on 22 February.[52] An exhibition about the stadium at the club museum was opened by former goalkeeper Jack Crompton and chief executive David Gill on 19 February.[52] The exhibition highlighted the history of the stadium and features memorabilia from its past, including a programme from the inaugural match and a 1:220 scale model hand-built by model artist Peter Oldfield-Edwards.[53] Finally, at Manchester United's home match against Fulham on 14 March, fans at the game received a replica copy of the programme from the first Old Trafford match, and half-time saw relatives of the players who took part in the first game – as well as those of the club chairman John Henry Davies and stadium architect Archibald Leitch – taking part in the burial of a time capsule of Manchester United memorabilia near the centre tunnel.[54] Only relatives of winger Billy Meredith, wing-half Dick Duckworth and club secretary Ernest Mangnall could not be found.[55]

Old Trafford was used as a venue for several matches in the football competition at the 2012 Summer Olympics.[56] The stadium hosted five group games, a quarter-final and semi-final in the men's tournament, and one group game and a famous semi-final in the women's tournament,[57] the first women's international matches to be played there.[58] Since 2006, Old Trafford has also been used as the venue for Soccer Aid, a biennial charity match initially organised by singer Robbie Williams and actor Jonathan Wilkes; however, in 2008, the match was played at Wembley Stadium.[59]

.jpg.webp)

On 27 March 2021, Old Trafford hosted its first game of the Manchester United women's team, with West Ham United as the opposition in the Women's Super League.[60] Exactly one year on, Manchester United's women's team face Everton at Old Trafford in front of a crowd for the first time (the 2021 game was behind closed doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic). A crowd of 20,241 attended the match, marking the highest home attendance of the women's team, and saw Manchester United come out with a 3–1 victory.[61]

On 6 July 2022, Old Trafford hosted the opening match of UEFA Women's Euro 2022 between England and Austria, in front of a record attendance for the Women's European Championships of 68,871 – the second highest women's football attendance in the United Kingdom.[62]

Old Trafford was included in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland's shortlist of stadiums to host UEFA Euro 2028 however was not included on the final list of 10.[63][64]

Structure and facilities

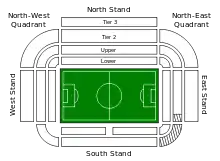

The Old Trafford pitch is surrounded by four covered all-seater stands, officially known as the Sir Alex Ferguson (North), East, Sir Bobby Charlton (South) and West Stands. Each stand has at least two tiers,[65] with the exception of the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, which only has one tier due to construction restrictions. The bottom tier of each stand is split into Lower and Upper sections, the Lower sections having been converted from terracing in the early 1990s.

Sir Alex Ferguson Stand

The Sir Alex Ferguson Stand, formerly known as the United Road stand and the North Stand, runs over the top of United Road. The stand is three tiers tall, and can hold about 26,000 spectators, the most of the four stands. It can also accommodate a few fans in executive boxes and hospitality suites.[66] It opened in its current state in 1996, having previously been a single-tiered stand. As the ground's largest stand, it houses many of the ground's more popular facilities, including the Red Café (a Manchester United theme restaurant/bar) and the Manchester United museum and trophy room. Originally opened in 1986 as the first of its kind in the world,[67] the Manchester United museum was in the south-east corner of the ground until it moved to the redeveloped North Stand in 1998. The museum was opened by Pelé on 11 April 1998, since when numbers of visitors have jumped from 192,000 in 1998 to more than 300,000 visitors in 2009.[68][69]

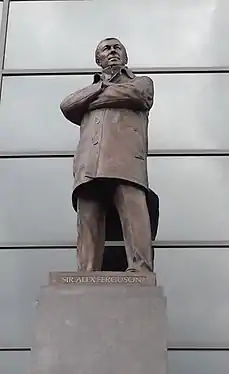

The North Stand was renamed as the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand on 5 November 2011, in honour of Alex Ferguson's 25 years as manager of the club.[70] A 9-foot (2.7 m) statue of Ferguson, sculpted by Philip Jackson, was erected outside the stand on 23 November 2012 in recognition of his status as Manchester United's longest-serving manager.[71]

Sir Bobby Charlton Stand

.jpg.webp)

Opposite the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand is the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, formerly Old Trafford's main stand and previously known as the South Stand. Although only a single-tiered stand, the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand contains most of the ground's executive suites,[72] and also plays host to any VIPs who may come to watch the match. Members of the media are seated in the middle of the Upper South Stand to give them the best view of the match. The television gantry is also in the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, so the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand is the one that gets shown on television least often.[26] Television studios are located at either end of the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, with the club's in-house television station, MUTV, in the East studio and other television stations, such as the BBC and Sky, in the West studio.

The dugout is in the centre of the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, raised above pitch level to give the manager and his coaches an elevated view of the game. Each team's dugout flanks the old players' tunnel, which was used until 1993. The old tunnel is the only remaining part of the original 1910 stadium, having survived the bombing that destroyed much of the stadium during the Second World War.[73] On 6 February 2008, the tunnel was renamed the Munich Tunnel, as a memorial for the 50th anniversary of the 1958 Munich air disaster.[74] The current tunnel is in the South-West corner of the ground, and doubles as an entrance for the emergency services. If large vehicles require access, then the seating above the tunnel can be raised by up to 25 feet (7.6 m).[75] The tunnel leads up to the players' dressing room, via the television interview area, and the players' lounge. Both the home and away dressing rooms were re-furbished for the 2018–19 season, and the corridor leading to the two was widened and separated to keep the opposing teams apart.[76]

On 3 April 2016, the South Stand was renamed the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand before kick-off of the Premier League home match against Everton, in honour of former Manchester United player Sir Bobby Charlton, who made his Manchester United debut 60 years earlier.[77][78]

West Stand

Perhaps the best-known stand at Old Trafford is the West Stand, also known as the Stretford End. Traditionally, the stand is where the hard-core United fans are located, and also the ones who make the most noise.[79] Originally designed to hold 20,000 fans, the Stretford End was the last stand to be covered and also the last remaining all-terraced stand at the ground before the forced upgrade to seating in the early 1990s. The reconstruction of the Stretford End, which took place during the 1992–93 season, was carried out by Alfred McAlpine.[80] When the second tier was added to the Stretford End in 2000, many fans from the old "K Stand" moved there, and decided to hang banners and flags from the barrier at the front of the tier. So ingrained in Manchester United culture is the Stretford End, that Denis Law was given the nickname "King of the Stretford End", and there is now a statue of Law on the concourse of the stand's upper tier.[81]

East Stand

The East Stand at Old Trafford was the second to be converted to a cantilever roof, following the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand. It is also commonly referred to as the Scoreboard End, as it was the location of the scoreboard. The East Stand can currently hold nearly 12,000 fans,[33] and is the location of both the disabled fans section and the away section; an experiment involving the relocation of away fans to the third tier of the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand was conducted during the 2011–12 season, but the results of the experiments could not be ascertained in time to make the move permanent for the 2012–13 season.[82] The disabled section provides for up to 170 fans, with free seats for carers. Old Trafford was formerly divided into sections, with each section sequentially assigned a letter of the alphabet. Although every section had a letter, it is the K Stand that is the most commonly referred to today. The K Stand fans were renowned for their vocal support for the club, and a large array of chants and songs, though many of them have relocated to the second tier of the Stretford End.[83]

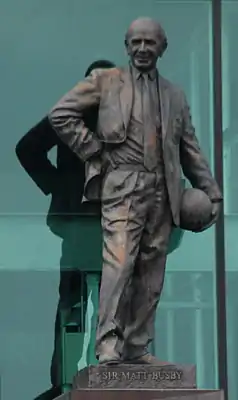

The East Stand has a tinted glass façade, behind which the club's administrative centre is located. These offices are the home to the staff of Inside United, the official Manchester United magazine, the club's official website, and its other administrative departments. Images and advertisements are often emblazoned on the front of the East Stand, most often advertising products and services provided by the club's sponsors, though a tribute to the Busby Babes was displayed in February 2008 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Munich air disaster. Above the megastore is a statue of Sir Matt Busby, who was Manchester United's longest-serving manager until he was surpassed by Sir Alex Ferguson in 2010. There is also a plaque dedicated to the victims of the Munich air disaster on the south end of the East Stand, while the Munich Clock is at the junction of the East and South Stands.[16] On 29 May 2008, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Manchester United's first European Cup title, a statue of the club's "holy trinity" of George Best, Denis Law and Bobby Charlton, entitled "The United Trinity", was unveiled across Sir Matt Busby Way from the East Stand, directly opposite the statue of Busby.[84][85]

The Manchester United club shop has had six different locations since it was first opened. Originally, the shop was a small hut near to the railway line that runs alongside the ground. The shop was then moved along the length of the South Stand, stopping first opposite where away fans enter the ground, and then residing in the building that would later become the club's merchandising office. A surge in the club's popularity in the early 1990s led to another move, this time to the forecourt of the West Stand. With this move came a great expansion and the conversion from a small shop to a "megastore". Alex Ferguson opened the new megastore on 3 December 1994.[86] The most recent moves came in the late 1990s, as the West Stand required room to expand to a second tier, and that meant the demolition of the megastore. The store was moved to a temporary site opposite the East Stand, before taking up a 17,000 square feet (1,600 m2) permanent residence in the ground floor of the expanded East Stand in 2000.[87] The floor space of the megastore was owned by United's kit sponsors, Nike, who operated the store until the expiry of their sponsorship deal at the end of July 2015, when ownership reverted to the club.[88]

Pitch and surroundings

The pitch at the ground measures approximately 105 metres (115 yd) long by 68 metres (74 yd) wide,[2] with a few metres of run-off space on each side. The centre of the pitch is about nine inches higher than the edges, allowing surface water to run off more easily. As at many modern grounds, 10 inches (25 cm) under the pitch is an underground heating system, composed of 23 miles (37 km) of plastic pipes.[89] Former club manager Alex Ferguson often requested that the pitch be relaid,[90] most notably half-way through the 1998–99 season, when the team won the Treble, at a cost of about £250,000 each time. The grass at Old Trafford is watered regularly, though less on wet days, and mowed three times a week between April and November, and once a week from November to March.[89]

In the mid-1980s, when Manchester United Football Club owned the Manchester Giants, Manchester's basketball franchise, there were plans to build a 9,000-seater indoor arena on the site of what is now Car Park E1. However, the chairman at the time, Martin Edwards, did not have the funds to take on such a project, and the basketball franchise was eventually sold.[91] In August 2009, the car park became home to the Hublot clock tower, a 10-metre (32 ft 10 in)-tall tower in the shape of the Hublot logo, which houses four 2-metre (6 ft 7 in)-diameter clock faces, the largest ever made by the company.[92]

The east side of the stadium is also the site of Hotel Football, a football-themed hotel and fan clubhouse conceived by former Manchester United captain Gary Neville. The building is located on the east side of Sir Matt Busby Way and on the opposite side of the Bridgewater Canal from the stadium, and can accommodate up to 1,500 supporters. It opened in the summer of 2015. The venture is conducted separately from the club and was funded in part by proceeds from Neville's testimonial match.[93]

Future

In 2009, it was reported that United continued to harbour plans to increase the capacity of the stadium further, with the next stage pointing to a redevelopment of the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, which, unlike the rest of the stadium, remains single tier. A replication of the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand development and North-East and North-West Quadrants would see the stadium's capacity rise to an estimated 95,000, which would give it a greater capacity than Wembley Stadium (90,000).[94] Any such development is likely to cost around £100 million, due to the proximity of the railway line that runs adjacent to the stadium, and the corresponding need to build over it and thus purchase up to 50 houses on the other side of the railway.[33] Nevertheless, the Manchester United group property manager confirmed that expansion plans are in the pipeline – linked to profits made from the club's property holdings around Manchester – saying "There is a strategic plan for the stadium ... It is not our intention to stand still".[95]

In March 2016 (ten years after the previous redevelopment), talk of the redevelopment of the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand re-emerged. In order to meet accessibility standards at the stadium, an £11 million investment was made into upgrading its facilities, creating 118 new wheelchair positions and 158 new amenity seats in various areas around the stadium, as well as a new purpose-built concourse at the back of the Stretford End.[96] Increasing capacity for disabled supporters is estimated to reduce overall capacity by around 3,000. To mitigate the reduction in capacity, various expansion plans have been considered, such as adding a second tier to the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, bringing it to a similar height to the Sir Alex Ferguson Stand opposite but without a third level and increasing capacity to around 80,000. Replication of the corner stands on the other side of the stadium would further increase its capacity to 88,000 and increase the number of executive facilities. Housing on Railway Road and the railway line itself have previously impeded improvements to the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand, but the demolition of housing and engineering advances mean that the additional tier could now be built at reduced cost.[97]

In 2018, it was reported that plans are currently on hold due to logistical issues. The extent of the work required means that any redevelopment is likely to be a multi-season project, due to the need to locate heavy machinery in areas of the stadium currently inaccessible or occupied by fans during match days and the fact that the stand currently holds the changing rooms, press boxes and TV studios. Club managing director Richard Arnold has said that "it isn't certain that there's a way of doing it which doesn't render us homeless." This would mean that Manchester United would have to leave Old Trafford for the duration of the works – and while Tottenham Hotspur were able to use the neutral Wembley Stadium for two seasons while their own new stadium was built, the only stadia of comparable size anywhere near Old Trafford are local rivals Manchester City's City of Manchester Stadium, or possibly Anfield, home of historic rivals Liverpool, neither of which are considered viable.[98]

In 2021 United co-chairman Joel Glazer said at a Fans Forum meeting that "early-stage planning work" for the redevelopment of Old Trafford and the club's Carrington training ground was underway. This followed "increasing criticism" over the lack of development of the ground since 2006.[99] The club is considering tearing down the current stadium and building an entirely new one on the same site, but this is believed to be the "least likely choice".[100]

Other uses

Rugby league

Old Trafford has played host to both codes of rugby football, although league is played there with greater regularity than union. Old Trafford has hosted every Rugby League Premiership Final since the 1986–87 season,[101] in addition to the competition's successor, the Super League Grand Final from 1998.[102]

The first rugby league match to be played at Old Trafford was held during the 1924–25 season, when a Lancashire representative side hosted the New Zealand national team, with Manchester United receiving 20 per cent of the gate receipts.[22] The first league match to be held at Old Trafford came in November 1958, with Salford playing against Leeds under floodlights in front of 8,000 spectators.[103]

The first rugby league Test match played at Old Trafford came in 1986, when Australia beat Great Britain 38–16 in front of 50,583 spectators in the first test of the 1986 Kangaroo tour.[104][105] The 1989 World Club Challenge was played at Old Trafford on 4 October 1989, with 30,768 spectators watching Widnes beat the Canberra Raiders 30–18.[106] Old Trafford also hosted the second Great Britain vs Australia Ashes tests on both the 1990 and 1994 Kangaroo Tours. The stadium also hosted the semi-final between England and Wales at the 1995 Rugby League World Cup; England won 25–10 in front of 30,042 fans. The final rugby league international played at Old Trafford in the 1990s saw Great Britain record their only win over Australia at the ground in 1997 in the second test of the Super League Test series in front of 40,324 fans.

.jpg.webp)

When the Rugby League World Cup was hosted by Great Britain, Ireland and France in 2000, Old Trafford was chosen as the venue for the final; the match was contested by Australia and New Zealand, and resulted in a 40–12 win for Australia, watched by 44,329 spectators.[107] Old Trafford was also chosen to host the 2013 Rugby League World Cup final.[108] The game, played on 30 November, was won by Australia 34–2 over defending champions New Zealand, and attracted a crowd of 74,468, a world record for a rugby league international.[109] During the game, Australia winger Brett Morris suffered a heavy crash into the advertising boards at the Stretford End, emphasising questions raised pre-match over the safety of Old Trafford as a rugby league venue, in particular the short in-goal areas and the slope around the perimeter.[110] In January 2019, Old Trafford was selected to host the 2021 Rugby League World Cup finals, with the men's and women's matches being played as a double header.[111]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 was the first year in which Old Trafford did not host the Super League Grand Final due to concerns about having to possibly reschedule the match, which Manchester United were unable to accommodate.[112]

Rugby union

Old Trafford hosted its first rugby union international in 1997, when New Zealand defeated England 25–8. A second match was played at Old Trafford on 6 June 2009,[113] when England beat Argentina 37–15.[114] The stadium was one of 12 confirmed venues set to host matches of the 2015 Rugby World Cup; however, in April 2013 United pulled out of the contract over concerns about pitch quality and not wanting to compromise their relationship with the 13-man code.[115]

Other sports

Before the Old Trafford football stadium was built, the site was used for games of shinty, the traditional game of the Scottish Highlands.[116] During the First World War, the stadium was used by American soldiers for games of baseball.[103] On 17 September 1981, the North Section of cricket's Lambert & Butler Floodlit Competition was played there; in the semi-finals, Nottinghamshire defeated Derbyshire and Lancashire beat Yorkshire, before Lancashire beat Nottinghamshire by 8 runs in the final to reach the national final, played between the other regional winners at Stamford Bridge the next day.[117] In October 1993, a WBC–WBO Super-Middleweight unification fight was held at the ground, with around 42,000 people paying to watch WBO champion Chris Eubank fight WBC champion Nigel Benn.[118][119]

Concerts and other functions

Aside from sporting uses, several concerts have been played at Old Trafford, with such big names as Bon Jovi, Genesis, Bruce Springsteen, Status Quo, Rod Stewart[120] and Simply Red playing. An edition of Songs of Praise was recorded there in September 1994.[103] Old Trafford is also regularly used for private functions, particularly weddings, Christmas parties and business conferences.[121] The first wedding at the ground was held in the Premier Suite in February 1996.[104]

Records

The highest attendance recorded at Old Trafford was 76,962 for an FA Cup semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Grimsby Town on 25 March 1939.[24] However, this was before the ground was converted to an all-seater stadium, allowing many more people to fit into the stadium. Old Trafford's record attendance as an all-seater stadium currently stands at 76,098, set at a Premier League game between Manchester United and Blackburn Rovers on 31 March 2007.[24] Old Trafford's record attendance for a non-competitive game is 74,731, set on 5 August 2011 for a pre-season testimonial between Manchester United and New York Cosmos.[122] The lowest recorded attendance at a competitive game at Old Trafford in the post-War era was 11,968, as United beat Fulham 3–0 on 29 April 1950.[123] However, on 7 May 1921, the ground hosted a Second Division match between Stockport County and Leicester City for which the official attendance was just 13. This figure is slightly misleading as the ground also contained many of the 10,000 spectators who had stayed behind after watching the match between Manchester United and Derby County earlier that day.[124]

The highest average attendance at Old Trafford over a league season was 75,826, set in the 2006–07 season.[125] The greatest total attendance at Old Trafford came two seasons later, as 2,197,429 people watched Manchester United win the Premier League for the third year in a row, the League Cup, and reach the final of the UEFA Champions League and the semi-finals of the FA Cup.[126] The lowest average attendance at Old Trafford came in the 1930–31 season, when an average of 11,685 spectators watched each game.[127]

Transport

Adjacent to the Sir Bobby Charlton Stand of the stadium is Manchester United Football Ground railway station. The station is between the Deansgate and Trafford Park stations on the Southern Route of Northern Rail's Liverpool to Manchester line. It originally served the stadium on matchdays only, but the service was stopped at the request of the club for safety reasons.[128][129] The stadium is serviced by the Altricham, Eccles, South Manchester and Trafford Park lines of the Manchester Metrolink network, with the nearest stops being Wharfside, Old Trafford (which it shares with the Old Trafford Cricket Ground) and Exchange Quay at nearby Salford Quays. All three stops are less than 10 minutes' walk from the football ground.[130]

Buses 255 and 256, which are run by Stagecoach Manchester and 263, which is run by Arriva North West run from Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester to Chester Road, stopping near Sir Matt Busby Way, while Stagecoach's 250 service stop outside Old Trafford on Wharfside Way and X50 service stops across from Old Trafford on Water's Reach.[131] There are also additional match buses on the 255 service, which run between Old Trafford and Manchester city centre.[132] Other services that serve Old Trafford are Arriva's 79 service (Stretford – Swinton), which stops on Chester Road and 245 (Altrincham – Exchange Quay), which stops on Trafford Wharf Road, plus First Greater Manchester service 53 (Cheetham – Pendleton) and Stagecoach's 84 service (Withington Hospital – Manchester), which stop at nearby Trafford Bar tram stop.[131] The ground also has several car parks, all within walking distance of the stadium; these are free to park in on non-matchdays.[133]

References

Bibliography

- Barnes, Justyn; Bostock, Adam; Butler, Cliff; Ferguson, Jim; Meek, David; Mitten, Andy; Pilger, Sam; Taylor, Frank OBE; Tyrrell, Tom (2001). The Official Manchester United Illustrated Encyclopaedia. London: Manchester United Books. ISBN 0-233-99964-7.

- Brandon, Derek (1978). A–Z of Manchester Football: 100 Years of Rivalry. London: Boondoggle.

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Patrick Stephens. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- Inglis, Simon (1996) [1985]. Football Grounds of Britain (3rd ed.). London: CollinsWillow. ISBN 0-00-218426-5.

- James, Gary (2008). Manchester – A Football History. Halifax: James Ward. ISBN 978-0-9558127-0-5.

- McCartney, Iain (1996). Old Trafford – Theatre of Dreams. Harefield: Yore Publications. ISBN 1-874427-96-8.

- Mitten, Andy (2007). The Man Utd Miscellany. London: Vision Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905326-27-3.

- Murphy, Alex (2006). The Official Illustrated History of Manchester United. London: Orion Books. ISBN 0-7528-7603-1.

- Rollin, Glenda; Rollin, Jack (2008). Sky Sports Football Yearbook 2008–2009. Sky Sports Football Yearbooks. London: Headline Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7553-1820-9.

- White, John (2007). The United Miscellany. London: Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-84442-745-1.

- White, John D. T. (2008). The Official Manchester United Almanac (1st ed.). London: Orion Books. ISBN 978-0-7528-9192-7.

Notes

- "Old Trafford". premierleague.com. Premier League. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- "Premier League Handbook 2022/23" (PDF). Premier League. p. 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Manchester Sightseeing Bus Tours". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Barnes et al., p. 45

- Murphy, p. 14

- Murphy, p. 27

- McCartney (1996), p. 9

- Inglis, pp. 234–235

- White, p. 50

- McCartney (1996), p. 13

- Inglis, p. 234

- McCartney (1996), p. 10

- Butt (1995), p. 247

- Butt, p. 178

- "Manchester Utd Football Gd (MUF)". National Rail. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Barnes et al., pp. 44–47, 52

- White (2008), p. 50

- "FA Cup Final Venues". TheFA.com. The Football Association. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "1911 FA Cup Final". fa-cupfinals.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- "1915 FA Cup Final". fa-cupfinals.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- Murphy, p. 31

- McCartney (1996), p. 17

- "The OT Story: 1910–1930". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 18 January 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Rollin and Rollin, p. 254–255

- Inglis, p. 235

- Brandon, pp. 179–180

- McCartney (1996), p. 20

- Murphy, p. 45

- Philip, Robert (1 February 2008). "How Matt Busby arrived at Manchester United". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- White (2008), p. 224

- Inglis, p. 236

- Inglis, p. 237

- "Old Trafford 1909–2006". manutdzone.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- Hibbs, Ben (15 August 2006). "OT atmosphere excites Ole". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Macchiavello, Martin (18 December 2009). "Nostalgia Alá vista" (in Spanish). Olé. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Pearson, Geoff (December 2007). "University of Liverpool FIG Factsheet – Hooliganism". Football Industry Group. University of Liverpool. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- Inglis, p. 238

- Inglis, pp. 238–239

- James, pp. 405–6

- Inglis, p. 239

- "Old Trafford". waterscape.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook 2012/13. Nyon: Union of European Football Associations. 2012. p. 154.

- "Men's Senior Team Results". TheFA.com. The Football Association. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Sinnott, John (7 February 2007). "England 0–1 Spain". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- "Man Utd 3–0 Birmingham". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 26 March 2006. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Coppack, Nick (31 March 2007). "Report: United 4 Blackburn 1". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Morgan, Steve (March 2010). McLeish, Ian (ed.). "Design for life". Inside United. Haymarket Network (212): 44–48. ISSN 1749-6497.

- Bartram, Steve (19 November 2009). "OT100 #9: Record gate". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Bostock, Adam (25 January 2010). "My Old Trafford". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Bartram, Steve (19 February 2010). "OT100: The Top 10 revealed". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Nichols, Matt (14 January 2010). "OT art competition". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Bartram, Steve (19 February 2010). "New OT exhibit unveiled". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 11 December 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Nichols, Matt (14 January 2010). "OT history on display". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Bostock, Adam (12 March 2010). "Stadium set for centenary match". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Nichols, Matt (14 March 2010). "Dream day for 1910 relatives". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Old Trafford". London2012.com. London 2012. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "Football – event schedule". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- Borden, Sam (30 July 2012). "Rare at Old Trafford: A Women's Match". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Gibson, Sean (3 June 2016). "Soccer Aid 2016, England vs Rest of the World: What time is kick-off, what are the teams and which TV channel is it on?". Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "MU Women to play first-ever match at Old Trafford". Manchester United (Press release). 16 March 2021. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "Manchester United Women 3–1 Eveton Women". BBC Sport. 27 March 2022. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- Hill, Courtney (7 July 2022). "Women's Euro 2022 kicks off with record attendance as England secure a nervous win". olympics.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- "Euro 2028: Casement Park and Everton's Bramley-Moore Dock among 10 stadiums for UK & Ireland bid". BBC Sport.

- "UK and Ireland announce final list of stadiums for Euro 2028 bid". The Athletic.

- "Seating Plan". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Executive Club". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Inglis, p. 240

- "Virtual Tour – The Museum". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Bartram, Steve (14 January 2010). "OT100 #66: Pele's visit". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Man Utd rename Old Trafford stand in Ferguson's honour". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 5 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- "Sir Alex Ferguson pride as Manchester United unveil statue". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "The Suites". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Virtual Tour – Dugout". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- "Football honours Munich victims". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- "Virtual Tour – Player's Tunnel". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- Wallace, Sam (28 August 2018). "Old Trafford dressing-room layout changed to avoid repeat of Manchester derby tunnel fracas". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Sir Bobby Charlton stand unveiled at Old Trafford". BBC News. 3 April 2016. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "South Stand at Old Trafford to be renamed after Sir Bobby Charlton". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 15 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Moore, Glenn (19 November 1996). "Football: You only sing when you're standing". London: Independent, The. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- "Alfred McAlpine wins £7.2m contract to redevelop Stretford End at Manchester United FC's stadium". The Construction News. 28 May 1992. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- "Denis Law". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Away fans won't move". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- Moore, Glenn (19 November 1996). "Football: You only sing when you're standing". The Independent. London: Independent Print. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- Hibbs, Ben (29 May 2008). "United Trinity honoured". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Man Utd 'trinity' statue unveiled". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- White (2008), p. 319

- Mitten, p. 137

- Bates, Steve (18 April 2015). "Manchester United planning military-style operation to purge Old Trafford of Nike branding". Mirror Online. MGN. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- White (2007), p. 17

- Nixon, Alan (30 January 2001). "Football: FA charges Neville as United tear up pitch". The Independent. London.

- Mitten, p. 122

- "Hublot clock unveiled". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Thompson, Gemma (17 May 2011). "Neville launches fans' HQ". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "Manchester United set to make Old Trafford bigger than Wembley". The Daily Telegraph. London. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "United scoring in property market". Manchester Evening News. MEN Media. 12 January 2013. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Richardson, Alice (15 January 2020). "Manchester United spend £11m to double Old Trafford disabled seating". Manchester Evening News. MEN Media. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Mitten, Andy (28 March 2016). "Manchester United consider expanding Old Trafford capacity to hold 80,000". ESPN FC. ESPN. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Stone, Simon (12 April 2018). "Man Utd: Sir Bobby Charlton Stand work at Old Trafford not imminent". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Stone, Simon (23 October 2021). "Manchester United in discussions over major redevelopment of Old Trafford". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- Jackson, Jamie (14 March 2022). "Manchester United considering Old Trafford demolition as part of revamp". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- "Memories of 1987 Old Trafford clash with Wigan". Warrington Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "Super League Grand Final: Old Trafford continues as host venue until 2020". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Mitten p. 138

- McCartney (1996), p. 94

- Fagan, Sean (2006). "Kangaroo Tour: 1986". RL1908.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- "Carnegie World Club Challenge 1989–90". superleague.co.uk. Super League. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- "Past Winners – 2000". Official Website of Rugby League World Cup 2008. BigPond. 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- "Rugby League World Cup: Old Trafford to host 2013 final". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Fletcher, Paul (30 November 2013). "Rugby League World Cup 2013: New Zealand 2–34 Australia". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- "Kangaroos have Old Trafford safety worries for Rugby League World Cup final against New Zealand". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Bower, Aaron (29 January 2019). "Old Trafford to host men's and women's finals of 2021 Rugby League World Cup". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- O'Brien, James (17 October 2020). "Hull considered as potential Grand Final host as Super League searches for Old Trafford alternative". HullLive. Local World. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- "England to play at Old Trafford". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- "England 37–15 Argentina". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "England will host 2015 World Cup". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 28 July 2009. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- Herbert, Ian (9 September 2006). "Top football clubs played host to Scots sport of shinty". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- "Lambert and Butler Floodlit Competition 1981". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- McCartney (1996), p. 74

- Bartram, Steve (9 October 2013). "Boxing's big night at OT". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Ferguson, Alex (22 March 1992). "Good pitches make for good matches". New Sunday Times. Kuala Lumpur: New Straits Times Press. p. 20. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- "Conferences & Events". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Marshall, Adam (5 August 2011). "United 6 New York Cosmos 0". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- "Season 1949/50 – Matches and Teamsheets". StretfordEnd.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- McCartney (1996), pp. 16–17

- "Season 2006/07 – Season Summary". StretfordEnd.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- "Season 2008/09 – Season Summary". StretfordEnd.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- James, p. 154

- "Network Map" (PDF). Northern Rail. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- "Manchester United Football Ground (MUF)". National Rail. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- "Metrolink – Walking route to Old Trafford" (PDF). Metrolink. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "Manchester South Network Map" (PDF). Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "255". Stagecoach Bus. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Maps & Directions". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

External links

- Old Trafford at ManUtd.com

.jpg.webp)