Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons

Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons, was a floating dry dock that served in the Dutch East Indies from 1869 till at least 1933. Up till about 1910 she was a crucial part of the Dutch naval infrastructure in the Indies.

Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons on the move to Sabang in 1898 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons |

| Ordered | 3 February 1863 |

| Awarded | 5 March 1863 |

| Builder | Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel |

| Cost | 366,685 guilders |

| Laid down | 1863 |

| Launched | 26 May 1869 |

| Decommissioned | July 1933 |

| Homeport |

|

| General characteristics (as completed) | |

| Length | 90.00 m (295.3 ft) (length p/p) |

| Beam | 24.00 m (78.7 ft) |

| Draft |

|

| Depth of hold | 8.05 m (26.4 ft) |

| Armour | none |

Context

At first Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was mostly known as: 'the iron dry dock', because there was only one iron dry dock in the Dutch East Indies. It was destined for Onrust Island, which housed one of the two naval bases in the Dutch East Indies. Previously there had been a wooden dry dock at Onrust Island. When the iron drydock arrived at Onrust it was designated as Onrust Iron Dock, or Iron Dock of Onrust. Later another iron dry dock was sent to Onrust Island. This necessitated to designate our drydock by its lift capacity of 3,000 tons, and eliminated the need for the label 'iron'. When the location of the dock changed, so did that part of the name. In the end it was referred to as Sabang Dock of 3,000 tons, but also as: 'the 3,000 tons dock', or 'the small dock at Sabang'.

Dry dock capacity had become very important with the introduction of the screw propelled ship. Traditional methods for maintaining ships required them to be put on shore. This was very dangerous for screw propelled ships, where the slightest deformation of the hull could block the screw axle. Meanwhile, screw propelled ships needed regular inspection. In a dry dock a screw ship rested on its keel. The risk to the hull was minimal, and an inspection could be done in a day.

Before its construction, in the 1850s, there were two wooden floating docks in the Dutch East Indies. Due to the increased demand the admiralty in the Dutch East Indies wanted to have a third, bigger floating dock. It foresaw that during the scheduled maintenance and repairs of the docks themselves, the remaining dock would not provide enough dry dock capacity. Furthermore, the existing dry docks were not capable to receive the biggest ships.[1] The wooden dock at Surabaya handled the Groningen-class corvettes of 1,780 tons with great difficulty. The wooden dock at Onrust was longer, but still not long enough, and was not capable to receive loaded ships.[2]

Due to the known condition of the grounds at the naval base Onrust near Batavia, and the experience gained in the attempt to construct a fixed dry dock at Onrust, the East Indies Authorities decided that a floating dry dock was required. The only doubt was whether it should be made of wood or iron. The decision to opt for an iron drydock was made in part because iron floating docks had already been made in the United Kingdom. Rennie and Sons in London had made an iron dry dock for the Spanish navy. Randolph, Elder & Co. had made an iron floating dock for the French navy at Saigon and an iron dry dock for Cores de Vries on Java.[2]

Construction and commissioning

Design

The authorities in the Dutch East Indies sent a design of the floating dry dock it required to the Netherlands. This was received in spring 1860.[3] This was the original design by C. Scheffer,[4] then a Navy engineer in Surabaya.[5] The East Indies authorities also proposed to place the order at Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel. The minister of the Colonies and the minister for the Navy thought differently. They decided that August Elize Tromp and J. Strootman (who wrote the article in the reference section) would make a revised plan. In 1862 they would visit England for that purpose.[2] In the end the revised design was very close to the original design.[6]

Ordering

The ministers for the navy and the Colonies decided to have a public tender. In mid-December 1862 the tender for the dry dock was announced by the minister of the navy Willem Huyssen van Kattendijke.[7] On 3 February 1863, the public tender for the iron dock in the East Indies was held. The list of 17 contestants reads like a who's who of Dutch industry at the time. Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel was the cheapest at 366,685 guilders.[2] Of the other offers that by Randolf Elder from Glasgow was highest at 695,700.[8][9] The contract was approved on 5 March 1863.[10]

| Name | Place | Country | Offer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 366,685 |

| D.A. Schretler & Wolfson (Koninklijke Nederlandse Grofsmederij) | Leiden | Netherlands | 390,000 |

| W.L. van Noort (Fijenoord) | Rotterdam | Netherlands | 443,450 |

| W. Poolman (Maatschappij tot Exploitatie van Staatsspoorwegen) | The Hague | Netherlands | 445,484 |

| H.P. van Heukelom (De Atlas) | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 464,970 |

| F. Kloos Kloos Kinderdijk | Alblasserdam | Netherlands | 472,700 |

| E. Reiniers & Co. | Maastricht | Netherlands | 473,262 |

| J. & K. Smit | Nieuw Lekkerland | Netherlands | 478,500 |

| H.H. Heijs | Delft | Netherlands | 499,000 |

| D. Kristi & Zn | Kralingen | Netherlands | 499,449 |

| R.W. Thomson | Glasgow | United Kingdom | 530,000 |

| Wed. Sterkman & Zn | The Hague | Netherlands | 550,000 |

| R.W. Thomson | Glasgow | United Kingdom | 580,000 |

| Bézier & Jonkheim | Rotterdam | Netherlands | 595,000 |

| Finch & Herch | Chepstow | United Kingdom | 597,000 |

| H. Noppen | Alphen | Netherlands | 640,000 |

| B. Randolph Elder | Glasgow | United Kingdom | 695,700 |

Construction

Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel would not build the drydock on one of her slipways. Instead it had a terrain between the boiler factory and the warehouses for the shipyard. There the bottom ash produced by the factory had been dumped for years, and consisted of a layer of about 2 m deep. With quite some effort it was made into a solid level underground to support the dock. Even so, part of it would sag a bit. The terrain was surrounded by a railroad with turntables, that led to the workshops. Most of the iron was delivered by Société des hauts-fourneaux, usines et charbonnages de Marcinelle et Couillet. Mr. B. van der Linde was the overseer of construction.[2]

In Amsterdam the dock would be constructed, but not entirely riveted. It would then be taken apart again and be assembled in Surabaya. Readying the construction site, and getting the iron took quite some time, and it was almost May before good progress was made. On 7 April 1864 Prince Napoléon Bonaparte visited the shipyard of Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel, and especially the iron floating drydock under construction.[11] On 9 June 1864 some members of the Royal Institute of Engineers visited the floating dock after attending their annual meeting. Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel made pictures and sent them to the members of the institute.[12] The final cost of the floating dock would be 460,852 guilders, of those 41,018 were for transport.[10]

In June 1864 the first one third extremity of the dock was taken apart, and in late July 1864 loading was started.[10] On 28 September 1864 the ships Regina Maris of Captain S. Ouwehand and Nederland of captain van A.A. van Steenderen left Texel for Surabaya carrying this part. The other extremity of the dock was loaded on Nieuwe Waterweg of captain E. von Lindern, while she was in Rotterdam. On 28 October 1864 she left from Brouwershaven. C. September 1864 the center of the dry dock was taken apart. This part would be sent on board Wilhelmina of Captain J. Snoek which would also be loaded in Rotterdam. Loading started in November, but soon ice blocked the inland canals, and so loading took till early February 1865. On 4 February 1865 Wilhelmina left Rotterdam under Captain H.J. Brauer. The Petronella would transport a final shipment of rivets.

| Ship Name | Size in 'Lasts' | Iron parts (kg) | Rivets in (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regina Maris | 399 | 331,284 | 20,880 |

| Nederland | 373 | 334,104 | 20,558 |

| Nieuwe Waterweg | 744 | 705,824 | 38,790 |

| Wilhelmina | 376 | 665,622 | 11,540 |

| Petronella | - | 16,870 |

Assembly in Surabaya

On 15 January 1865 Nederland arrived in Surabaya with 1,687 pieces of iron.[13] On 24 January Regina Maris arrived. Their cargo consisted of 498,000 of sheet iron, 91,200 kg of angle- and T-Iron bars up to 13 m long, 165,000 kg of frames and 45,800 kg of rivets.[14] On 9 February 1865 Nieuwe Waterweg arrived in Surabaya with a comparable cargo.[15] On 27 May 1865 Wilhelmina of Captain H.J. Brauer arrived in Surabaya.[16]

Meanwhile, in Surabaya, preparations had been made to create a place were the drydock could be assembled. On 9 January 1864 a tender was held to create a suitable terrain for assembly in Surabaya. The terrain (called 'dock pit') was to be surrounded by dykes and have a number of warehouses.[17] In Surabaya Mr. B. van der Linde was again overseer for assembly.[18]

After the first shipments had arrived assembly of Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons could start. On 3 April 1865 the first parts of the 'pontoon' were assembled. The idea was that as soon as the 'pontoon' was finished, it would be brought to deeper water, where the higher parts would be assembled.[12] It would take over four years before the pontoon left the dock pit and entered the basin (the harbor of Surabaya). This happened at spring tide on 26 May 1869.[19]

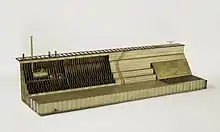

Model of the drydock

It was customary that a shipyard offered a model of the ship to the principal.[20] In the case of the drydock this was a was rather lavish brass model. It represents one-half of two-thirds of the length, complete with steam engine, pumps, piping, sluices and valves. It is a piece of high-quality workmanship, executed in great detail, with sections of walls that open and shut to reveal the interior. The entire construction has been followed accurately: all the frames and bulkheads have been fitted, even in the parts that do not open and are inaccessible to the eye. Not all the rivets have been clinched, though thousands of tiny holes have been drilled through the brass sheets and frames. The model likely approaches the condition of the dock when it was temporarily assembled in Amsterdam rather than the finished product in the East Indies.[21]

In 1867 the model was in the Dutch section of the International Exposition in Paris. The famous writer Vice Admiral Edmond Pâris thought the Dutch section the most interesting of those of the maritime nations after that of the United Kingdom and France.[22] The model of HNLMS Adolf van Nassau (1861) drew his attention, and so did the model of the clipper Nestor launched by Smit Kinderdijk in 1866. The model of Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was the largest piece of the Dutch section, but was only briefly mentioned by him.[22] Others thought the Dutch part of the exhibition was not interesting except for the part about drydocks.[23] The model became part of the model collection of the navy, that is now part of the Rijksmuseum. It had been in storage there since 1925, when in the 1990s it was decided that it should be part of the permanent exposition, and was restored to its former splendor.[23]

Characteristics

The floating dock was 90 m long, with a beam of 24 m and a height of 10.55 m. The depth of hold was given as 8.05 m 'on the iron upper or dock floor', which is a strange definition of hold. On the inside the dock was smallest at the floor, with a width of 12.30 m. On top it had a maximum width of 21 m. The bottom of the dry dock was a kind of pontoon. This pontoon had three longitudinal bulkheads and six transverse bulkheads, dividing it in 28 compartments. Thickness of these bulkheads was 10–13 mm.[2] The weight of the dock was 2,126,472 kg

The water would be pumped out of the pontoon by two steam engines situated at the height of the second walkway. These were high pressure steam engines of 20 nominal hp. The cylinder had a diameter of 45 cm and a stroke of 36 cm with a pressure of 2.5-3 atm. Two belt pulleys of 1.62 m diameter drove two Gwynnes centrifugal pumps. Together these four pumps had to pump out 6,000 m3 of water in two hours in order to completely raise the dock. A system of tubes and valves made it possible to regulate the amount of water that remained in each compartment. This was especially important when shorter ships were docked. By leaving more water in the compartments that were not 'under' the ship, less strain was put on the dock.[24]

According to the plan Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons would be able to lift a fully loaded screw frigate, weighing 3,000 tonnes.[10] The units that fitted this description were the largest ships of the Dutch navy. These screw frigates were not permanently stationed in the east, but could be deployed there, and so a repair facility was required. The question is whether the Adolf van Nassau of 3,750 displacement could be lifted by the dock.

When construction started, Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was one of the first floating dry docks. As such she had a few particularities. On the inside she was still shaped like a ship, as were traditional dry docks on land. Newer dry docks would soon abandon this shape. She was made in one piece. Newer dry docks would soon be made of connecting pontoons. The big advantage was that this made them 'self docking', because they could dock their own parts. Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons could not, and so the big question was: Where would the dry dock dock? Another development was that soon most dry docks would shift to electrical power, and would get it from shore.

Service

At Surabaya 1869

On 3 October 1869 the first ship was serviced by Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons.[25] This was a trial run to establish that the dry dock was water tight, and that everything functioned. On 27 October 1869 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons finally left Surabaya harbor towed by Timor and two tugboats.[26] On the open sea she was towed by Timor and Ardjoeno, with Amsterdam on guard.[27]

At Onrust 1869-1880

On 4 November 1869 the convoy with Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons reached Onrust Island, where the dock was moored on the southern side[27] Since 1 January 1869 civilian ships were no longer allowed in the government dry docks. Now the merchant community of Batavia saw a very well equipped dry dock that it was not allowed to use, and so protests followed.[28] An exception had been made for the Nederlands Indische Stoomvaart Maatschappij (NISM). In 1870 the Vice Admiraal Fabius and Willem III of the NISM did use the dock.[29] HNLMS Java was also docked in 1870. In December 1871 HNLMS Curaçao used the dock. In 1872 Vice Admiraal Koopman and Coehoorn used the dry dock, and so did the ocean liner SS Prins van Oranje, which had her screws repaired in the dock. In 1874 the Evertsen-class frigate Zeeland was in the dock to be turned into a guard ship.[30] Zeeland was one of the 3,000 tons frigates that the dock was supposed to be able to lift.

Meanwhile Onrust Wooden Dock had been repaired and had served at Surabaya. It was expected to arrive at Onrust in September 1874. Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons would then be towed to Surabaya, and undergo some repairs in the dock pit. It was expected that parts (schoorijzers) at the bottom of the pontoon would be corroded.[30]

Onrust Wooden Dock arrived at Onrust in November 1874. On 9 November 1874 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was then towed to Surabaya by HNLMS Banka and HNLMS Sumatra as well as Koningin Sophia of the NISM. On 13 November it arrived in Surabaya. By the date 1877-1878 of the photograph one can assume that during these repairs the steam engines were moved from inside the dock to the top deck of the dock. One can also conclude that the photo shows Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons in the dock pit. In October 1877 the repairs of Iron Drydock of Onrust were finished.[31] On 21 October 1877 SS G.G. Loudon, SS Japara and SS Vice President Prins left Batavia for Onrust. They would pick up Onrust Wooden Dock, bring her to Surabaya, and then return with Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons.[32] The wooden dock indeed arrived at Surabaya in October 1877.[33]

On 2 November 1877 these ships arrived back in Batavia from Surabaya.[34] They most probably did tow Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons, because many ships were docked at Onrust in February 1878.[35] On 19 October 1878 HNLMS Gedeh was docked in the big iron dock at Onrust.[36] The label 'big' reflected that a small iron dock (the cylinder dock) for the harbor works of Batavia had meanwhile arrived.

On 10 October 1880 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons left Onrust towed by Japara, Koning Willem III and Baron Bentinck.[37] On their return voyage these ships would tow a new dry dock of 5,000 tons from Surabaya to Onrust. Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons would itself dock and be repaired at the dock pit in Surabaya, which was prepared in the third quarter of 1880.[38]

At Surabaya 1880-1891

While at Surabaya Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was reported as not ready on 4 February 1881.[39] By mid-February the repairs were reported ready, and dredging work was started to get the dry dock from the 'Geul' to the basin of Surabaya.[40] In April 1881 she was reported to have arrived in the basin.[41]

From August 1884 till April 1886 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was repaired. On 26 Augustus 1884 she was brought into the dock pit at Surabaya, and put onto blocks.[42] In October 1884 these repairs were not expected to be finished before 1886.[43] On 6 April 1886 the dock was indeed towed out of the basin.[44]

From April 1886 till October 1891 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons regularly served in Surabaya. The bigger Onrust Dock of 5,000 tons was brought from Onrust to Surabaya to almost immediately take her place to be repaired in the dock pit.[45] Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons then served during the whole year 1887. In February 1888 boilers were ordered locally for the 'small iron dock'.[46] In April 1888 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was joined by a smaller floating dock of 1,400 tons.[47] also built by the Koninklijke Fabriek.

At Batavia 1891-1896

In 1877 the Dutch government had started the construction of a harbor for Batavia at Tanjung Priok. This harbor lacked a good repair facility. It had only the small Volharding Dock at nearby Untung Jawa (Amsterdam Island), which was too small for most modern ships. In June 1890 the government came to an agreement with David Croll to create a repair shipyard and docking facility at Tanjung Priok. Part of the deal was that Croll would lease Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons for 6% of its book value. He would also lease the cylinder dock free of charge, and lease a drydock that would be built in the Netherlands. By law of 12 November 1890 this agreement was approved.[48] It would lead to the establishment of the Droogdok-maatschappij Tandjong Priok (dry dock company Tanjung Priok).

On 15 October 1891 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons left the basin at Surabaya.[49] In November 1891 she was handed over to the Droogdok-maatschappij Tandjong Priok. Soon after the company started its business. In 1893 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons served 76 ships for 313 docking days.[50] In 1894 the dock served 85 ships for 343 docking days.[51] In 1895 the dock was in almost continuous use, serving 83 ships for 385 (sic!) docking days.[52] After Tanjung Priok Dock of 4,000 tons, the dry dock especially built for Tanjung Priok had arrived, Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was towed back to Surabaya in November 1896.

At Surabaya 1896-1898

After arrival in Surabaya, Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was brought into the dock pit. An inspection proved that it was economical to repair her. Repairs started with several structural parts getting replaced. She would also get a wooden and zinc skin. Repairs were first expected to be finished in October 1897.[53] After having been repaired Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons served in Surabaya from 14 February 1898 - 18 March 1898, servicing 8 vessels for 65 days. She then left for Sabang.[54]

At Sabang 1900-1933

In July 1889 a commission was appointed to review the organisation of the navy in the Dutch East Indies. On 20 April 1891 it reported that: Next to the dry dock at Tanjung Priok there was an urgent need for docking capacity elsewhere in the Dutch East Indies. In the first place in Northern Sumatra. In mid 1897 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was then ordered to be towed to Sabang, Aceh.

There was a comment that Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was not an optimal docking solution for Sabang: The dock could dock most warships, but it was probably too small for the protected cruisers of the Holland-class and the small armored cruisers of the Evertsen-class[55] The comment gives an idea about the capacities of the dry dock in 1890. However, the designated military use of the dry dock was not to service these warships meant to defend the East Indies against external enemies. One of the primary reasons to establish the harbor of Sabang was that it could service the many ships involved in the Aceh War,[56] and these were much smaller. The cost of these warships being based in Padang or traveling about 2,500 km from Aceh to Batavia to get inspected in a dry dock was prohibitive.

Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons arrived in Sabang in 1898. She was not immediately commissioned because of problems with the anchoring. In June 1898 HNLMS Sumbawa was docked.[54] The harbor of Sabang served a military and a commercial purpose.[57] From 1 August 1900 the drydock was leased to the company Zeehaven en Kolenstation Sabang N.V.[58] In 1910 the dock was destined to be broken up. Instead it was transferred for free to the company Zeehaven en Kolenstation Sabang N.V. In return this company had to keep the drydock operational till 1 December 1910, and to offer free docking to ships of the East Indies government.[59] Not much is known about the activity of the dock at Sabang, but the company continued to operate the dock till at least 1924.

On account of the launch of a new 5,000 tons dock for Sabang in 1924, the old dock was reported as requiring repairs. These could only be cost-effective if its already limited capacity was further reduced, but at the time the ships using Sabang were approaching 4,000 - 5,000 tons.[60] Therefore, the Sabang port authority had ordered the new 5,000 tons dock. There is a photograph of this new drydock lying next to Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons, with a ship on Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons.[61] This is how we know it was operational till at least October 1924.

It would be expected that the dock would then be broken up, but this was not the case. In September 1924 the Sabang port authority asked permission to moor her old dock and the new dock side by side on the pier connected to her factory and warehouses.[62] Later photo's show this situation.[63] So the life of Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was again extend for a few years. The above-mentioned repairs that reduced the lift capacity of the old dry dock took place. It could no longer lift 3,000 tons, but it was kept in exploitation for lighter work till it was broken.

When these defects came up the Dutch East Indies were in a serious economic crisis brought about by the Great Depression. It made that repair was not feasible. Therefore, in about July 1933 Onrust Dock of 3,000 tons was towed to open sea. The valves were opened, and so it sank in 300 meter deep water. For 35 years the dry dock had been a landmark in Sabang, the first harbor that most Dutchmen saw on their way to the Indies. In total it had served for 64 years. By the time that it was discarded most people did not know where it came from. Some thought that it had arrived in the Indies sailing around the cape.[64]

Notes

- Tromp & Strootman 1865, p. 10.

- Tromp & Strootman 1865, p. 11.

- Lemmers 1998, p. 64.

- Lemmers 1998, p. 67.

- "Photograph of a Floating Dry Dock". Rijksmuseum. 9 February 2020.

- Lemmers 1998, p. 69.

- "Ministerie van Marine". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 14 December 1862.

- "Binnenland". Nieuw Amsterdamsch handels- en effectenblad. 5 February 1863.

- "Binnenland". De Eer der Nederlandsche IJzer-Industrie gehandhaafd. 1 April 1863.

- Tromp & Strootman 1865, p. 17.

- "Amsterdam 8 April". Rotterdamsche courant. 9 April 1864.

- Tromp & Strootman 1865, p. 18.

- "In en uitvoer te Soerabaja van 14 en 16 Jan. 1865". De Oostpost. 17 January 1865.

- "Bevrachtingen der Nederlandsche Handel-maatschappij". Java-bode. 3 September 1864.

- "Bevrachtingen der Nederlandsche Handel-maatschappij". Java-bode. 5 October 1864.

- "Scheepsberichten". De Oostpost. 30 May 1865.

- "Uitbesteed". De Oostpost. 19 December 1863.

- "Binnenland". Rotterdamsche courant. 27 December 1864.

- "Vertrokken passagiers". Bataviaasch handelsblad. 9 June 1869.

- Lemmers 1998, p. 72.

- Lemmers 1998, p. 73.

- Pâris 1869, p. 370.

- Lemmers 1998, p. 63.

- Tromp & Strootman 1865, p. 14.

- "Gemengde Indische Berichten". De locomotief. 8 October 1869.

- "Soerabaija, 27 October 1869". Bataviaasch Handelsblad. 3 November 1869.

- "Aangekomen en vertrokken passagiers te Batavia". Java-bode. 6 December 1869.

- "Nederlandsch Indië". Java Bode. 26 November 1870.

- "Nederlandsch Eskader". Bataviaasch handelsblad. 18 February 1871.

- "Uit de Bataviaasche bladen". De Locomotief. 4 September 1874.

- "Voornaamste verrigtingen aan de marine-etablissementen". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 12 April 1878.

- "Nederlandsch Indië". De Locomotief. 25 October 1877.

- "Uit het pas verschenen werk van de Waal over onze indische financiën". Soerabaijasch handelsblad. 1 December 1880.

- "Aangekomen Schepen". Java-bode. 3 November 1877.

- "Tandjong Priok". Java-bode. 30 March 1878.

- "Men schrijft ons van Onrust". Bataviaasch handelsblad. 4 November 1878.

- "Scheepsberichten". De Locomotief. 15 October 1880.

- "Voornaamste verrigtingen aan de marine-etablissementen". Nederlandsche Staatscourant. 14 January 1881.

- "Soerabaja, 4 Febr". Java-Bode. 9 February 1881.

- "Nederlandsch Indië". De Locomotief. 17 February 1881.

- "Nederlandsch Indië". Java-Bode. 29 April 1881.

- "Soerabaya 26 Augustus". Bataviaasch handelsblad. 1 September 1884.

- "Verspreide Indische Berigten". De Locomotief. 14 October 1884.

- "Soerabaia 6 April". Soerabaijasch handelsblad. 6 April 1886.

- "Batavia, 13 June 1888". Bataviaasch handelsblad. 13 June 1888.

- "Versrpeide Indische Berichten". De Locomotief. 27 February 1888.

- "Maritieme Inrichtingen". De locomotief. 1 November 1888.

- "Wet van den 12den November 1890". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 27 November 1890.

- "Soerabaia, 16 October". Soerabaijasch handelsblad. 16 October 1891.

- "Nieuws uit Nederland". De locomotief. 21 June 1894.

- "Plaatselijk Nieuws". Bataviaasch handelsblad. 10 July 1895.

- "De Mail". Java-bode. 8 June 1896.

- Departement van Marine 1898, p. 608.

- Departement van Marine 1899, p. 279.

- "Poeloe-Weh, Zeehaven". De locomotief. 14 August 1897.

- Krüsemann 2015, p. 13.

- "Een nieuwe Nederlandsche haven in het wereldverkeer". De Maasbode. 8 November 1903.

- "Departement der Marine". De locomotief. 4 August 1900.

- "Uit het koloniaal verslag 1910". De Preanger-bode. 12 October 1910.

- "Een dok voor Sabang". De Sumatra post. 4 June 1924.

- Ruud van der Sluis (2011). "Cornelis Douwesweg 23 (A)". NDSM Werfmuseum. NDSM Werfmuseum. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- "Nieuws uit Sabang". Het Nieuws van den Dag. 30 September 1924.

- Krüsemann 2015, p. 1.

- "Het Sabangsche 3000-ton dok +". Bataviaasch nieuwsblad. 4 August 1933.

References

- Tromp, A.E.; Strootman, J. (1865), "IJzeren drijvend dok voor de marine in Oost Indië", Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut van Ingenieurs, Gebroeders J & H van Langenhuysen, Amsterdam, pp. second part 10–18

- Lemmers, Alan (1998), "The Historical Experience of a Scaled-Down Nineteenth Century Drydock" (PDF), The Northern Mariner, Canadian Nautical Research Society, p. 62

- Pâris, Edmond (1869), L'Art naval à l'Exposition universelle de Paris en 1867, Librairie Maritime et Scientifique, Paris, pp. 370–372

- Krüsemann, Bart (2015), Sabang: haven in de rimboe (PDF), Leiden University

- Departement van Marine (1898), "Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Zeemacht 1896-1897", Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Zeemagt, De Gebroeders van Cleef 's Gravenhage

- Departement van Marine (1899), "Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Zeemacht 1897-1898", Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Zeemagt, De Gebroeders van Cleef 's Gravenhage