Gran Sasso raid

During World War II, the Gran Sasso raid (codenamed Unternehmen Eiche, German pronunciation: [ʊntɐˌneːmən ˈaɪ̯çə] ⓘ, literally "Operation Oak", by the German military[1]) on 12 September 1943 was a successful operation by German paratroopers and Waffen-SS commandos to rescue the deposed Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini from custody in the Gran Sasso d'Italia massif. The airborne operation was personally ordered by Adolf Hitler, approved by General Kurt Student and planned and executed by Major Harald Mors.

| Gran Sasso raid | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |

Mussolini with German commandos | |

| Type | Prison escape with outside help |

| Location | Hotel Campo Imperatore, Italy 42°26′32.73″N 13°33′31.66″E |

| Planned by | Harald Mors |

| Target | Campo Imperatore |

| Date | 12 September 1943 |

| Executed by | |

| Outcome | Benito Mussolini escaped from prison |

| Casualties | 2 Italians killed, 10 Germans wounded |

Background

On the night between 24 and 25 July 1943, a few weeks after the Allied invasion of Sicily and bombing of Rome, the Grand Council of Fascism voted a motion of no confidence against prime minister Benito Mussolini. On the same day, King Victor Emmanuel III replaced him with Marshal Pietro Badoglio[2] and had Mussolini arrested.[3] This is commonly known as the Fall of the Fascist regime in Italy (or 25 Luglio in Italian); Badoglio's government at first continued the war on the Axis powers' side,[4] but after Italian and German forces were defeated during the Allied invasion of Sicily (17 August), the Italian government began secret negotiations with the Allies to surrender. This resulted in the Armistice of Cassibile on 3 September, coinciding with the Allied invasion of mainland Italy.[5]

Preparations

Badoglio government

The Italian high command, led by Marshal Badoglio, was well aware that the German army would probably try to seize control of Italy as soon as the government switched sides to the Allies. Therefore, the Italian government wanted the Allied troops to have landed on the mainland before the armistice took effect and was announced publicly – which happened on 8 September[5] – so that the Allies could move north quickly to help defend especially the capital city of Rome against the looming German invasion. Indeed, Mussolini's fall prompted German military commanders to develop Operation Achse (the plans, originally codenamed Operation Alarich, were changed several times from 28 July to 30 August) to mitigate the impact of a potential Italian defection as much as possible.[4] The Badoglio government also realised that the Germans were likely to attempt breaking Mussolini out of prison, reinstate him and rally Fascist support to keep Italy in the war on Germany's side, and so strict measures to hide and secure Mussolini were taken: he was moved several times and guarded by almost a battalion of troops.[6]

Mussolini's imprisonment

Mussolini was arrested on the king's orders by the Carabinieri on 25 July just after he left the king's private residence, and he was initially brought to the Podgora Carabinieri Headquarters in Trastevere.[7] In the afternoon he was transferred to the Carabinieri Cadet School in the vía Legnano, where he was held until 27 July.[7] On 27 July, military police led by general Francesco Saverio Pólito took Mussolini to Gaeta, boarded the ship Persefone and imprisoned Mussolini in an isolated house on the island of Ponza in the Tyrrhenian Sea from 12:00 on 28 July to 7 August.[8] From 7-27 August, Mussolini was held in a private villa on La Maddalena.[9][5] From 28 August,[10] he was kept at the Hotel Campo Imperatore, which was built on a remote and defendable mountain plateau 2,112 metres above sea level in the Gran Sasso d'Italia mountain range.[11] A ski station was located next to the hotel,[12] linked with a cable car. The hotel was one of originally three planned hotels (but the only one that was ever built) shaped in the letters 'D', 'V' and 'X', together 'DVX', the Latin word meaning "leader", from which Mussolini's Italian title il Duce was derived.[11] The D-shaped Hotel Campo Imperatore constructed to celebrate Mussolini's rule served as his prison for several weeks.[11]

German tracking and planning

Adolf Hitler's common procedure was to give similar orders to competing German military organisations. He ordered Hauptsturmführer Otto Skorzeny to track Mussolini and simultaneously ordered the paratroop General Kurt Student to execute the liberation. On September 7, German signals intelligence intercepted a coded Italian report which indicated that Mussolini was imprisoned somewhere in the Abruzzi mountains.[6] Next, the Germans employed a ruse to confirm the exact location in which a German doctor pretended to try to establish a hospital at the hotel on the Grand Sasso.[6] Informants of SS-Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler used counterfeit notes with a face value of £100,000 forged under Operation Bernhard to help obtain information. Skorzeny used information gathered by agents to plan his raid.

Raid

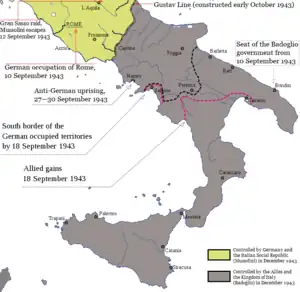

After the Italian government announced the Armistice of Cassibile and thereby its defection from the Axis to the Allies on 8 September, the German army launched Operation Achse and quickly occupied strategic points in northern and central Italy within days, effectively disarming hundreds of thousands of Italian soldiers who had nominally just switched sides.[4] The Allied Italian military and political leaders including Marshal Badoglio and King Victor Emmanuel III fled to Allied-controlled territory in southern Italy.[5]

On 12 September 1943, Skorzeny and 16 SS troopers joined the Fallschirmjäger to rescue Mussolini in a high-risk glider mission. Ten DFS 230 gliders, each carrying nine soldiers and a pilot, towed by Henschel Hs 126 planes started between 13:05 and 13:10 from the Pratica di Mare Air Base, near Rome.

The leader of the airborne operation, Oberleutnant Georg Freiherr von Berlepsch, entered the first glider while Skorzeny and his SS troopers sat in the fourth and the fifth gliders. To gain height before crossing the close by Alban Hills, the leading three glider-towing plane units flew an additional loop. All of the following units considered that manoeuvre to be unnecessary and preferred not to endanger the given time of arrival at the target. That led to both of Skorzeny's units arriving first over the target.[13]

Meanwhile, the valley station of the funicular railway leading to the Campo Imperatore was captured at 14:00 in a ground attack by two paratrooper companies, led by Major Harald Mors, the commander-in-chief of the whole raid, which cut all telephone lines. This ground attack caused the only two deaths of the operation, Italian forestry guard Pasqualino Vitocco, who was killed while attempting to warn the garrison of the approaching German troops, and carabiniere Giovanni Natale, who was killed while preparing to open fire on the attackers. Two more carabinieri were slightly wounded by a hand grenade.[14][15][16] At 14:05, the airborne commandos landed their ten DFS 230 gliders on the mountain near the hotel. One crashed and caused injuries.

The Fallschirmjäger and Skorzeny's special troopers overwhelmed Mussolini's captors, 200 well-equipped Carabinieri guards, without a single shot being fired. The Italian General Fernando Soleti had been forced to fly with Skorzeny on the raid, as a hostage; making himself known to the soldiers who guarded the hotel, Soleti ordered them not to shoot. Skorzeny attacked the radio operator and his equipment and stormed into the hotel, followed by his SS troopers and the paratroopers. Ten minutes after the beginning of the raid, Mussolini left the hotel, accompanied by the German soldiers. At 14:45, Mors accessed the hotel via the funicular railway and introduced himself to Mussolini.

Mussolini was then to be flown out by a Fieseler Fi 156 STOL plane that had arrived in the meantime. Although under the given circumstances the small plane was overloaded, Skorzeny insisted on accompanying Mussolini, which endangered the mission's success.

After an extremely dangerous but successful takeoff, they flew to Pratica di Mare. They then immediately continued to fly in a Heinkel He 111 to Vienna, where Mussolini stayed overnight at the Hotel Imperial. The next day he was flown to Munich, and on 14 September, he met Hitler at Führer Headquarters, in Wolf's Lair, near Rastenburg.[17]

Aftermath

After hearing of Mussolini's escape, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stated in the House of Commons: "Knowing that il Duce was hidden in a safe place and that the Government of Badoglio was committed to handing him over to the Allies, a daring attack, completely beyond all foresight, prevented this from happening".[18]

The operation granted a rare public relations opportunity to Hermann Göring late in the war, with German propaganda hailing the operation for months afterward. The landing at Campo Imperatore was in fact led by First Lieutenant von Berlepsch, commanded by Major Mors and under orders from General Student, all of whom were Fallschirmjäger officers, but Skorzeny stewarded the Italian leader right in front of the cameras.

After an SS propaganda coup at the behest of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, Skorzeny and his special forces of the Waffen-SS were granted the majority of the credit for the operation. Skorzeny received a promotion to Sturmbannführer, the award of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and the fame that led to his image as the "most dangerous man in Europe".[13]

Skorzeny published an autobiography in 1950 (Geheimkommando Skorzeny) and another book (Meine Kommandounternehmen) in 1976.[19]

Historian Ulrich Trumpener (2015) stated that 'exaggerated credit [for the operation] was later given to a small SS detachment under Otto Skorzeny'.[4] Historian Óscar González López stated that Skorzeny was a 'fake liberator' created by Nazi propaganda, calling the Fallschirmjäger the 'legitimate protagonists' of the Gran Sasso raid.[18]

After the raid, Hitler put Mussolini in charge of a puppet state in German-occupied northern Italy, the Italian Social Republic, which served as a collaborationist regime of the Germans in their fight against the Allies, the Kingdom of Italy, now a co-belligerent of the Allies, and the Italian resistance.

In late April 1945, in the wake of near total defeat, Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci attempted to flee to Switzerland,[20] but both were captured by Italian communist partisans and summarily executed by firing squad on 28 April 1945 near Lake Como.

See also

Footnotes

- López 2018, p. 17–19.

- Whittam, John (2005). Fascist Italy. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4004-3.

- Annussek, Greg (2005). Hitler's Raid to Save Mussolini. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81396-2.

- Trumpener, Ulrich (2015). "ACHSE (AXIS), Operation (9 September–October 1943)". World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 1351. ISBN 9781135812492. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- Encarta Winkler Prins Encyclopaedia (1993–2002) s.v. "Badoglio, Pietro; Mussolini, Benito Amilcare Andrea; Wereldoorlog, Tweede §3.5 Geallieerde invasie op Sicilië". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Schuster, Carl O. (2015). "Gran Sasso raid (12 September 1943)". World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 1519. ISBN 9781135812492. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- López 2018, p. 17.

- López 2018, p. 19–20.

- López 2018, p. 20.

- López 2018, p. 58.

- López 2018, p. 23.

- López 2018, p. 18.

- Óscar González López (2007). Fallschirmjäger at the Gran Sasso. Valladolid: AF Editores. ISBN 978-84-96935-00-6.

- Pasqualino Vitocco e Giovanni Natale, due militari cancellati dalla storia

- L'ospite della camera 201

- Settembre 1943: I giorni della vergogna

- Erich Kuby: Verrat auf deutsch. Wie das Dritte Reich Italien ruinierte. Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1982, ISBN 3-455-08754-X.

- López, Óscar González (2018). Freeing Mussolini: Dismantling the Skorzeny Myth in the Gran Sasso Raid. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781526719997.

- My Commando Operations (see p. 228-284)

- Viganò, Marino (2001), "Un'analisi accurata della presunta fuga in Svizzera", Nuova Storia Contemporanea (in Italian), 3

External links

Media related to Gran Sasso raid at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gran Sasso raid at Wikimedia Commons