Order of the Rüdenband

The Order of the Rüdenband (i.e. dog collar), Society with the Rüdenband, or Rüdenbänder was a chivalric order established in the late 14th century in Silesia, Upper Lusatia and Northern Bohemia. In the early 15th century it was headed by Piast Duces of Silesia, most prominently by Louis II of Brzeg. Under him the Rüdenband gained members in Franconia, Swabia, and Austria.

History

The first evidence of the Order of the Rüdenband is a gift bestowed on dy rodinbender in 1389 according to an account book of the city of Görlitz.[1] Its formation was likely influenced by the establishment of the duchy of Görlitz for John of Görlitz, the youngest son of Charles IV.[2] In 1402 some members of the Order shared the captivity of king Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia in Vienna and left their Coats of arms with the badge of the Rüdenband in the armorial of the Saint Christopher fraternity.[3]

In 1413 a statute of association was enacted by the duces and the senior members of the Order of the Rüdenband.[4] The recording of the statutes might have been provoked by dynastic tensions between Louis II of Brzeg and his half brother Henry IX of Lubin. The conflict between Poland and the Teutonic Order, the Plague or a feud with the Duchy of Opole have also been considered.[5] The statutes might have been inspired by the Order of the Dragon, established in 1408 by Sigismund of Hungary. Louis II was a member of this order and a close retainer of Sigismund. Close relations of other members of the Order to the court of the later King of Germany and Bohemia have prompted historians to assume the Order an instrument of Sigismunds influence in the realm of his brother Wenceslaus.[6]

In 1416 a Portuguese herald captured the display of the Order in Constance.[7] The presence of Louis II and other members of the Order in Sigismunds retinue at the time of the Council of Constance attracted members from Southern Germany to join the Rüdenband.[8] In 1420 Louis II made the young margrave John the Alchemist captain of the Order in Franconia, Swabia and Bavaria. The new branch of the society pledged to support the augustinian monastery of Langenzenn.[9] The Rüdenband therefor might have influence the Order of the Swan by Johns brother Frederick II in 1440.[10]

In its prime the Order might have had 700 male and as much female members according to the travel account of Guillebert de Lannoy. Ghillebert was admitted to the Order by Louis II in 1414 when he traveled through Silesia.[11] The leading position of Louis II and the burden placed on society by the Hussite Wars caused the Order to fade away after his death in 1436. There is currently no evidence of the society in Silesia, Bohemia and Lusatia after 1425.[12] A last reverberation can be found in 1460, when the Constancian patrician Heinrich Blarer was depicted with the badges of the Rüdenband and the Order of the Jar.[13]

Statute of 1413[14]

Members of the Order of the Rüdenband were compelled to keep the peace among themselves and decide conflicts by arbitration or by judgement of one of the duces. In quarrels with non-members members, they were supposed to support each other, especially in case of captivity or inculpable harm. Only women and men of aristocratic conduct were allowed to join the Order. According to Ghillebert de Lannoy women made up half the membership of the Order. Their admission was probably conducted in the context Minne. Male members were only allowed to join the Order at one of its courts or tourneys.

Tourneys (hoff, literally courts) of the Order of the Rüdenband were to be held annually in Legnica or Görlitz after the feast of Saint Martin. Place and time of the tourneys could be changed by the duces and senior members. A matching sequence of tourneys was held in November 1388 and 1389 in Legnica and Görlitz respectively.[15] In 1413 no tourney was held, but instead a requiem was endowed at the Collegiate church in Legnica. Attendance of a requiem mass was supposed to conclude any following tourneys. All members of the Order were supposed to advertise the tourney of the Order when they join other tourneys.

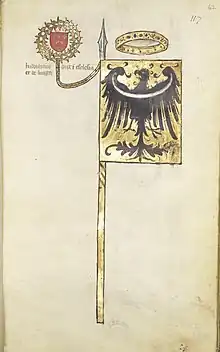

In 1413 the Order of the Rüdenband had a hierarchical structure with the bishop of Wrocław as its most prominent member, followed by the duces, senior members and the rest of the membership. In 1420 Louis II calls himself the geselleschaffte mit dem Rüdenpand oberster Haubtmann und geber (the society of the Rüdenband supreme captain and leader). Margrave John even calls him the king of the Order in 1425.[16] The former hierarchy is depicted in the Portuguese armorial. Members of knightly status are furthermore distinguished with golden Rüdenband-badges, while esquires are attached to silver ones.[17]

The rank of the members is also reflected by their membership fee: 720 groschen for the bishop, 360 groschen for the duces and 60 groschen for other members. The fee was supposed to cover for the requiem and the costs of the annual tourney. Abandoning the order cost a fee of 180 groschen. A penalty of 12 groschen was due if a member was encountered without wearing the badge of the Rüdenband. A member could be expelled for rejecting the arbitration of a duce, for unauthorised admission of a man to the Order (though if the perpetrator were a duce, the sentence was reduced to a fine), or for engaging in unaristocratic conduct.

In 1413 the Order had 6 chapters, each headed by 4 seniors. Four of the chapters, for the Duchy of Legnica, for the Duchies of Świdnica, Brzeg and Wrocław, for the Duchies of Żagań and Głogów, for the Duchies of Oleśnica and Koźle, as well as for Upper Lusatia and Bohemia.

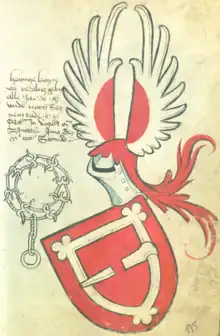

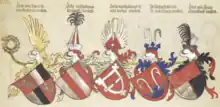

Heraldry

The badge of the Order of the Rüdenband was a spiked wolf collar. In armorials the badge is depicted either besides the coat of arms or around the shield. Depictions have been found in the Vienna manuscript of the armorial of the St. Christopher fraternity, in the Portuguese armorial John Rylands Library Latin Ms. 28, on a portrait of Heinrich Blarer in the Rosengarten museum in Constance and in the armorial by Conrad Grünenberg. In an inventory of the treasury of Frederick I, Elector of Saxony a silberin vorgult rodenband (a gilded Rüdenband made of silver) has been found among other insignia of knightly orders. A golden Rüdenband with pearls was commissioned by king Sigismund in 1418.[18]

References

- Crudelius, Johann Christian Carl (1775), Excerpta aus denen alten Raths-Rechnungen der Stadt Görlitz, Manuskript, fol. 19r The critical edition Jecht, Richard (1910), Die ältesten Görlitzer Ratsrechnungen bis 1419, Görlitz: Oberlausitzische Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, pp. 129, l. 3ff has the faulty emendation dy rodin bender (the red ribbons). For the lost original source and the transcript made by Crudelius, see Jecht Ratsrechnungen, p. VI and IX.

- For the residence of John of Görlitz, see Hoche, Siegfried (2007), "Herzogtum Görlitz (1377–1396)", in Bobková, Lenka; Konvicna, Jana (eds.), Rezidence a správní sídla v zemích České koruny ve 14.-17. století, Prag: Univerzita Karlova, Filozofická Fakulta, pp. 403–412. For the tourneys at the new princely court in 1380/1381 with guests from Silesia and Saxony see Gelbe, Richard (1883), "Herzog Johann von Görlitz", Neues Lausitzisches Magazin, vol. 59, pp. 1–201, esp. pp. 31f, 82 Tourneys would have been a regular occurrence in Görlitz. In 1389 the city council had to send a messenger to Prague scissitandum, utrum hastiludium processum haberet annon (anne deberemus edificare) i. e. to ask wether the (series of) tourney(s) should continue and preparations should be made, see Jecht, Die ältesten Görlitzer Ratsrechnungen, p. 64 l. 22ff, p. 71 l. 11ff und p. 77 l. 8ff and p. 142 l. 14.

- Ledel, Eva Katharin (2017), Die Wiener Handschrift des Wappenbuchs von Sankt Christoph auf dem Arlberg (Dissertation), Wien, p. 41, doi:10.25365/thesis.48846

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Clocriand von Rachenau - another member of the Order was left in Vienna after Wenceslaus' escape, see Mayer, Anton, ed. (1901), Regesten aus in- und ausländischen Archiven, mit Ausnahme des Archivs der Stadt Wien, Wien: Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Wien, pp. 183, No. 4263–4265, 4268, 4272–4274, 4276f For the "Second Captivity of Wencelsaus" see Schmidt, Ondřej (2017), "Druhé zajetí Václava IV. z italské perspektivy", Studia Mediaevalia Bohemica, vol. 9, pp. 163–214 Hlaváček, Ivan (1994), "Die Wiener Haft Wenzels IV. der Jahre 1402–1403 aus diplomatischer und verwaltungsgeschichtlicher Sicht", in Pánek, Jaroslav; Polívka, Miloslav; Rejchrtová, Noemi (eds.), Husitství – Reformace – Renesance, Praha, pp. 225–238{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) And Hlaváček, Ivan (2013), "König Wenzel (IV.) und seine zwei Gefangennahmen (Spiegel seines Kampfes mit dem Hochadel sowie mit Wenzels Verwandten um die Vorherrschaft in Böhmen und Reich)" (PDF), Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae, vol. 18, pp. 115–149, archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-23 - Published by Markgraf 1915.

- Kruse, Kamenz 1991, p. 251

- Čapský, Martin (2012), "Der Briefverkehr Sigismunds von Luxemburg mit schlesischen Fürsten und Städten", in Hruza, Karel; Kaar, Alexandra (eds.), Kaiser Sigismund (1368–1437), Wien: Böhlau, pp. 255–266, esp. p. 258, doi:10.7767/9783205210917.255 (inactive 2023-08-22)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - s. John Rylands Library Latin MS 28, Digitalisat p. 117ff. About the source Paravicini, Werner (2008), "Signes et couleurs au concile de Constance. Le témoinage d'un héraut d'armes portugais", in Turrel, Denise; et al. (eds.), Signes et couleurs des identités politiques de Moyen Âge à nos jours, Rennes, pp. 155–187, esp. pp. 158ff

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Albrecht von Neidberg is depicted with a golden Rüdenband around 1413 in the St. Christopher armorial, see Ledel, Die Wiener Handschrift des Wappenbuchs von Sankt Christoph auf dem Arlberg, S. 41. DOI:10.25365/thesis.48846 About the von Neidberg see Posch, Fritz (1977), "Das steirische Ministerialengeschlecht der Nitberg-Neitberg (Neuberg), seine steirischen und österreichischen Besitzungen und seine Beziehungen zum Kloster Lilienfeld", in Ebner, Herwig (ed.), Festschrift für Friedrich Hausmann, Graz: Akad. Dr.- und Verl.-Anst., pp. 409–440, esp. pp. 419f

- Spieß 1783

- Kruse, Kamenz 1991, p. 254

- 700 is assumed to be an exaggeration by Kruse, Kamenz 1991, p. 250 fn. 1. For Ghilleberts account see Potvin, Charles; Houzeau, Jean-Charles, eds. (1878), Oeuvres de Ghillebert de Lannoy, voyages, diplomate et moraliste, Louvain, p. 48

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kruse, Kamenz 1991, p. 250. Markgraf 1915, p. 90. Unconvincing Kaczmarek 1991, p. 17 and Schultz, Alwin (1892), Deutsches Leben im XIV. und XV. Jahrhundert, vol. 2, Wien, p. 378

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Both assume, that the siden Band (silken ribbon) bestowed upon Sebastian Ilsung in ainer stat ist nit fer von Rom (in a town not far from rome) by a Grossfürst und her von der großen Glogau (High prince and lord of Greater Głogów), see Hausleutner, Peter (1793), "Auszug aus dem Ilsung. Ehrenbuch", Schwäbisches Archiv, vol. 2, pp. 338–343, esp. p. 341 can be amendet to mean Rüdenband. The prince of Głogów is Władysław of Głogów who attended Emperor Frederick III. on his coronation campaign to Rome. There is no known relation of the duces of Těšín to the Order of the Rüdenband. - Konrad, Bernd (1993), Rosengartenmuseum Konstanz, die Kunstwerke des Mittelalters (Bestandskatalog), Konstanz, p. 40

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Markgraf 1915.

- Jecht Ratsrechnungen, p. 117 l. 5, p. 119 l. 1, p. 142 l. 14. The later tourney was planned, but canceled.

- Spieß 1785.

- Paravicini 2010, p. 162f.

- Schumm 1977/1981, p. 50f. Streich, Brigitte (1989), "Die Itinerare der Markgrafen von Meißen - Tendenzen der Residenzbildung", Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte, vol. 125, pp. 159–188, esp. p. 185

Bibliography

- Bretschneider, Paul (1925), "Schlesische Gesellschaftsorden" [Silesian Chivalric Orders], Schlesische Monatshefte, 2 (7): 337–344

- Kaczmarek, Romuald (1991), "Stowarzyszenie "obroźy psa gończego". Z dziejów świeckich zakonów rycerskich na średniowiecznym Śląsku" [The Society of the Rüdenband. The History of Chivalric Orders in medieval Silesia], Poznańskie-Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk – Sprawozdania Wydziału Nauk o Sztuce, 108: 13–23

- Kruse, Holger; Kamenz, Kirstin (1991), "Rüdenband (1413)", in Kruse, Holger; Paravicini, Werner; Ranft, Andreas (eds.), Ritterorden und Adelsgesellschaften im spätmittelalterlichen Deutschland, Frankfurt/Main, pp. 250–255, ISBN 978-3-631-43635-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Markgraf, Hermann (1915), "Über eine schlesische Rittergesellschaft am Anfange des 15. Jahrhunderts (Rüdenband)" [About a Silesian Chivalric Society in the early 15th century (Rüdenband)], Kleine Schriften zur Geschichte Schlesiens und Breslaus, Breslau, pp. 81–95

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paravicini, Werner (2010), "Von Schlesien nach Frankreich, England, Spanien und zurück. Über die Ausbreitung adliger Kultur im späten Mittelalter" [From Silesia to France, England, Spain and back. About the Dispersion of noble Culture in the Late Middle Ages], in Harasimowicz, Jan; Weber, Matthias (eds.), Adel in Schlesien. Herrschaft – Kultur – Selbstdarstellung, München, pp. 135–205, ISBN 978-3-486-58877-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schumm, Marianne (1981), "Die Gesellschaft mit dem Rüdenband" [The Society with the Rüdenband], Jahrbuch des Historischen Vereins für Mittelfranken, 89: 50–56, ISSN 0341-9339

- Spieß, Philipp Ernst (1783), "Von der Gesellschaft mit dem Rüdenband" [About the Society with the Rüdenband], Archivische Nebenarbeiten und Nachrichten vermischten Inhalts mit Urkunden, vol. 1, Halle, pp. 101–103