Orthography of Smal-Stotskyi and Gartner

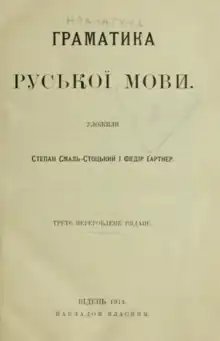

Orthography of Smal-Stotskyi and Gartner[1] (Ukrainian: Правопис Смаль-Стоцького і Ґартнера, romanized: Pravopys Smal-Stotskoho i Gartnera), also Orthography of Smal-Stotskyi[2][3][4] and Scientific Orthography[5] (Ukrainian: Правопис науковий, romanized: Pravopys naukovyi) is a Ukrainian orthography created on the basis of Zhelekhivka by Stepan Smal-Stotskyi in collaboration with Theodor Gartner. One of the main innovations of spelling was that the authors also adapted Zhelekhivka for foreign words. In 1891, under the pseudonym Stepan Nahnybida, Smal-Stotskyi published a description of his spelling principles in a 16-page pamphlet On Ruthenian Orthography.[6] In 1893, Smal-Stotskyi and Gartner published the Ruthenian Grammar, which listed all the phonetic rules of this spelling in practice.

Thanks to the authors' petitions to the Austrian government, the Ruthenian Grammar was approved in 1893 as an official textbook for schools in Galicia and Bukovina.

The new orthography has finally supplanted the etymological principle. It is characteristic that in this spelling, in comparison with zhelekhivka, there was very little new, and maybe even steps aside; but the important thing was that this spelling gained government approval. Since then, phonetic orthography has prevailed in Galicia. This victory of phonetics over etymology in Galicia and Bukovina, after seven years of stubborn struggle, happened mainly because it was supported by governmental factors, because Smal-Stotskyi and Gartner convinced them of the great benefits of orthography reform. However, many contemporary Ukrainian scholars in Chernivtsi and Lviv strongly opposed the change to traditional etymological spelling.

It is noteworthy that the greatest opposition to the introduction of the spelling of Smal-Stocki and Gartner was the then largest foreign enemies of Ukraine, the Russian Empire: the Russian government diplomatically officially protested against the change in Ukrainian Orthography initiated by Smal-Stotskyi and Gartner from etymological to phonetic.[7][8][9]

Basic principles of orthography

The alphabet consists of 33 letters, as today, including the letter ґ; the letter ь takes the last place in the alphabet, as in the Ukrainian orthography of 1928. Some letters differ in name from the present ones: г — ha (/ɦɑ/), but ґ — (/ɡɛ/), й — yi (/ɪ[[Near-close near-front unrounded vowel|j]]/), ь — yir ([[Near-close near-front unrounded vowel|jir]]). The most characteristic feature of the text written in this spelling is a rather abundant use of the letter it, which immediately catches the eye.

Use of the letters ї and і

The difference in the use of the letters ї and і is based on the soft and hard pronunciation of the д, т, з, с, ц, л, н before і. If i arose from ѣ or e, then the previous consonant from this group is greatly softened and in this case ї is written: дїд, дїя, тїло, сїяти, сїчень, оцї, слїд, слїпий, стїна, лїд, нїс (from несу).

In those cases when і appears with o, or if according to Ukrainian phonetics the consonant cannot be soft, but only slightly softened (labial, pharyngeal, hissing, etc.), it is always written і, and the previous consonant is pronounced firmly: ніч (ночі), сіль (соли), діл (долу), стіл (стола), спосіб (способу), осіб (особа), ніг (нога), відірвати, відійти, дійти, бідність, гордість, милість, злість (from бідности, гордости, милости, злости).

Use of iotated letters and apostrophes

The iotated letters я, є, ї, ю by the letters д, т, з, с, ц, л, н soften the previous sound, by the letters б, п, в, ф, м denote the iotation /jɑ/, /jɛ/, /ji/, /ju/, the apostrophe is not written, because it is considered an extra sign, because the soft pronunciation of lip sounds in the Ukrainian language is impossible and erroneous.

According to this rule, it is written: дядина, дїд, медведю, тягар, житє, тїло, житю, зятя, князю, ся, короля, лїд, нинї. Here iotated indicate the softness of the previous sound.

In such cases, iotated letters always denote two sounds: яйце, краєм, їсти, їв, Юрко (beginning of a word or a vowel), and in the words: пятий, імя, бєш, вїду, вюн, Стефюк apostrophe is considered unnecessary, because, as already mentioned, the lips can not be pronounced softly.

The apostrophe is used only when it is necessary to indicate that д, т, з, с, ц, л, н do not soften: з'їсти, з'явив ся, від'їхати, ад'юнкт.

Designation of softness

The softening is denoted by the letter ь at the end of the words (будь, зять, князь, місяць, біль), перед о (мальований, пятьох, сього, сьому, всього), а також перед іншим твердим приголосним (будьмо, батько, возьми, вельми, киньте, сьвіт, цьвіт). In words like сьвятий, сьвіт, цьвіт — marked with a letter in the sound /ʋ/ is always solid. Instead, before soft consonants, the softness of the previous one is not indicated in any way: кість, мисль, боязнь, шість; кістьми, шістьох.

Adjective suffixes -ск-, -цк- in contradistinction to the modern orthography are not softened : руский, шведский, Головацкий, французкий.

Sources and notes

- Кость Кисілевський. Історія українського правописного питання: Спроба синтези // Записки НТШ (Том CLXV): Збірник Філологічної секції (Т. 26); у виданні НТШ в ЗДА, книжка 3. Редактор: д[окто]р Кость Кисілевський. Нью-Йорк; Париж, 1956. 135 стор.: С. 74—114

- Анна Будзяк. Правописні ідеї Степана Смаль-Стоцького // Miejsce Stefana Smal-Stockiego w slawistyce europejskiej. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. 160 стор.: С. 23-35. ISBN 978-83-233-3333-3; e-ISBN 978-83-233-8718-3 (Studia Ruthenica Cracoviensia)

- Володимир Старик. Буковина на фронтах правописних воєн // Володимир Старик. Між націоналізмом і толерантністю. Чернівці: Прут. 2009. 186 стор.: С. 153-157

- Петро Самоверський. Письмо, правопис і його історія: 14. Грінченківка // Ілюстрований календар "Просвіти" на звичайний рік. Аргентина: Накл. Українського т-ва "Просвіта" в Аргентині, 1953. С. 58

- Петро Самоверський. Письмо, правопис і його історія: 13. Правопис науковий // Ілюстрований календар "Просвіти" на звичайний рік. Аргентина: Накл. Українського т-ва "Просвіта" в Аргентині, 1953. С. 58

- С. Нагнибіда. Про руську правопись. Львів. 1891. 16 стор.

- Іван Огієнко. Історія українського правопису Огієнко, Іван (2001). Історія української літературної мови. Київ: Наша культура і наука. p. 440. ISBN 966-7821-01-3.

- Історія українського правопису: XVI-XX століття: хрестоматія (PDF). Київ: Наукова думка. 2004. p. 582. ISBN 966-00-0261-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-01.

- Упоряд.: В.В. Німчук, Н.В. Пуряєва. (2004). Історія українського правопису XVI-XX століття. Хрестоматія. Київ: Наукова думка. ISBN 966-00-0261-0. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

Через підручник С. Смаль-Стоцького й Т. Гартнера "Руска граматика" (перше видання — 1893), затверджений Міністерством освіти Австро-Угорщини, вдосконалена желехівка стала нормативною в Галичині та на Буковині й протрималася там до 1922 р.