Ottokar I of Bohemia

Ottokar I (Czech: Přemysl Otakar I.; c. 1155 – 1230) was Duke of Bohemia periodically beginning in 1192, then acquired the title of King of Bohemia, first in 1198 from Philip of Swabia, later in 1203 from Otto IV of Brunswick and in 1212 (as hereditary) from Frederick II. He was an eminent member of the Přemyslid dynasty.

| Ottokar I | |

|---|---|

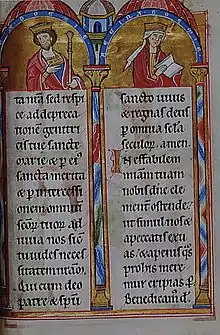

Contemporary relief carving of Ottokar I in the tympanum of St George's Convent, Prague | |

| Duke/King of Bohemia | |

| Reign | 1192–1193 1200[1]–1230[2] |

| Coronation | 1203, Prague |

| Successor | Wenceslaus I |

| Born | c. 1155 Bohemia |

| Died | 15 December 1230 (aged 75) Prague |

| Burial | |

| Spouses | Adelheid of Meissen Constance of Hungary |

| Issue more... | Wenceslaus I, King of Bohemia Dagmar, Queen of Denmark Anne, Duchess of Silesia Vladislaus II of Moravia Saint Agnes |

| Dynasty | Přemyslid |

| Father | Vladislaus II, Duke of Bohemia |

| Mother | Judith of Thuringia |

Early years

Ottokar's parents were Vladislaus II, Duke of Bohemia, and Judith of Thuringia.[3] His early years were passed amid the anarchy that prevailed everywhere in the country. After several military struggles, he was recognized as ruler of Bohemia by Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI in 1192.[4] He was, however, soon overthrown for joining a conspiracy of German princes to bring down the Hohenstaufen dynasty. In 1197, Ottokar forced his brother, Duke Vladislaus III, to abandon Bohemia to him and to content himself with Moravia.

Taking advantage of the civil war in Germany between the Hohenstaufen claimant Philip of Swabia and the Welf candidate Otto IV, Ottokar declared himself King of Bohemia in 1198,[5] being crowned in Mainz.[6] This title was supported by Philip of Swabia, who needed Czech military support against Otto.

In 1199, Ottokar divorced his wife Adelheid of Meissen,[6] a member of the Wettin dynasty, to marry Constance of Hungary, the young daughter of Hungarian King Béla III.[7]

In 1200, with Otto IV in the ascendancy, Ottokar abandoned his pact with Philip of Swabia and declared for the Welf faction.[8] Otto IV and later Pope Innocent III[9] subsequently accepted Ottokar as the hereditary King of Bohemia.[4]

Golden Bull of Sicily

Ottokar was quickly forced back into Philip's camp by the imperial declaration of a new duke of Bohemia, Děpolt III.[9] Subject to his recognition as duke, Ottokar had to allow his divorced wife to return to Bohemia.[9] Having been completed this condition, he again ranged himself among Philip's partisans and still later was among the supporters of the young King Frederick II. In 1212 Frederick granted the Golden Bull of Sicily to Bohemia. This document recognised Ottokar and his heirs as Kings of Bohemia.[5] The king was no longer subject to appointment by the emperor and was only required to attend Diets close to the Bohemian border. Although a subject of the Holy Roman Empire, the Bohemian king was to be the leading electoral prince of the Holy Roman Empire and to furnish all subsequent emperors with a bodyguard of 300 knights when they went to Rome for their coronation.

Ottokar's reign was also notable for the start of German immigration into Bohemia and the growth of towns in what had until that point been forest lands. In 1226, Ottokar went to war against Duke Leopold VI of Austria after the latter wrecked a deal that would have seen Ottokar's daughter (Saint Agnes of Bohemia) married to Frederick II's son Henry II of Sicily. Ottokar then planned for the same daughter to marry Henry III of England, but this was vetoed by the emperor, who knew Henry to be an opponent of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. The widowed emperor himself wanted to marry Agnes, but by then she did not want to play a role in an arranged marriage. With the help of the pope, she entered a convent.

Family

Ottokar was married first in 1178 to Adelheid of Meissen (after 1160 - 2 February 1211),[10] who gave birth to the following children:

- Vratislav of Bohemia (d. bef. 1225).[10]

- Dagmar of Bohemia (d. 24 May 1212),[10] married to King Valdemar II of Denmark.

- Božislava of Bohemia (d. 6 Feb bef. 1238), married to Count Henry I of Ortenberg.

- Hedvika of Bohemia, became a nun in Gernrode.

In 1199, he married secondly to Constance of Hungary (1181 – 6 December 1240),[10] who gave birth to the following children:

- Vratislav of Bohemia (c. 1200 – bef. 1209).[10]

- Judith of Bohemia (Judita) (- 2 June 1230), married to Bernhard von Spanheim, Duke of Carinthia.[11]

- Anne of Bohemia (Anna Lehnická) (1204 - 23 June 1265), married to Henry II the Pious, High Duke of Poland.[12]

- Anežka of Bohemia, died young.

- Wenceslaus I of Bohemia (Václav I.) (c. 1205 - 23 September 1253), became King of Bohemia.[10]

- Vladislaus of Bohemia (Vladislav) (1207 - 18 February 1227), Margrave of Moravia.[10]

- Přemyslid (Přemysl) of Bohemia (1209 - 16 October 1239), Margrave of Moravia, married to Margaret of Merania, daughter of Otto I, Duke of Merania.[10]

- Wilhelmina of Bohemia (Vilemína Česká, Guglielmina Boema) (1210 - 24 October 1281)

- Saint Agnes of Bohemia (Anežka Česká) (20 January 1211 – 6 March 1282)

References

- Sommer, Třeštík & Žemlička 2009, p. 209.

- France 2006, p. 233.

- Wihoda 2015, p. 298.

- Bradbury 2004, p. 70.

- Merinsky & Meznik 1998, p. 51.

- Lyon 2013, p. 146.

- Lyon 2013, p. 146-147.

- Toch 1999, p. 379.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 410.

- Wihoda 2015, p. 299.

- Loud & Schenk 2017, p. xxxii.

- Klaniczay 2000, p. 204.

Sources

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c.900–c.1300. Cambridge University Press.

- Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge.

- France, John (2006). The Crusades and the Expansion of Catholic Christendom, 1000–1714. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134196180.

- Klaniczay, Gábor (2000). Holy Rulers and Blessed Princesses: Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe. Translated by Palmai, Eva. Cambridge University Press.

- Loud, Graham A.; Schenk, Jochen, eds. (2017). The Origins of the German Principalities, 1100-1350: Essays by German Historians. Taylor & Francis.

- Lyon, Jonathan R. (2013). Princely Brothers and Sisters: The Sibling Bond in German Politics, 1100-1250. Cornell University Press.

- Merinsky, Zdenek; Meznik, Jaroslav (1998). "The making of the Czech state: Bohemia and Moravia from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries". In Teich, Mikulas (ed.). Bohemia in History. Cambridge University Press.

- Sommer, Petr; Třeštík, Dušan; Žemlička, Josef (2009). Přemyslovci Budování českého státu (in Czech). Praha: Nakladatelství Lidové noviny. ISBN 978-80-7106-352-0.

- Toch, Michael (1999). "Germany and Flanders: Welfs, Hohenstaufen and Habsburgs". In Abulafia, David (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 5, C.1198–c.1300. Cambridge University Press. pp. 375–404.

- Wihoda, Martin (2015). Vladislaus Henry: The Formation of Moravian Identity. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004303836.

External links

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ottakar I.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 367–368.