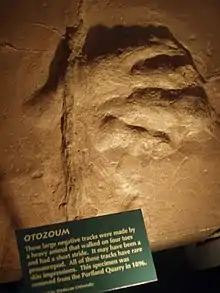

Otozoum

Otozoum ("giant animal") is an extinct ichnogenus (fossilized footprints and other markings) of sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Late Triassic-Middle Jurassic sandstones. Footprints were made by heavy, bipedal or, sometimes, quadrupedal animals with a short stride that walked on four toes directed forward.[1] These footrints are relatively large, over 20 cm in pes length.[1] Otozoum differs from Plateosaurus by having a notable homopody.[2]

| Otozoum Temporal range: Late Triassic - Middle Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Otozoum moodii footprint | |

| Trace fossil classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Ichnofamily: | †Otozoidae |

| Ichnogenus: | †Otozoum Hitchcock, 1847 |

| Ichnospecies | |

| |

Discovery and naming

Otozoum tracks were discovered by American paleontologist Edward Hitchcock, who described Otozoum as the "most extraordinary track yet brought to light in this valley [the Connecticut River] representing a bipedal animal... distinguished from all others... in the sandstone of New England". The ichnogenus was named by him in 1847, after the giant Otus.[3]

Hitchcock noted the excellent preservation of some tracks, preserving details of the skin, pads, and even impressions of Jurassic raindrops. Excellent Otozoum specimens from the Portland Quarry may be seen in the Dinosaur State Park and Arboretum in Rocky Hill, Connecticut.

Taxonomy

In 1953, Yale University paleontologist Richard Swann Lull revised Hitchcock's work, suggesting that the track maker might have been a prosauropod. Other sources have been proposed, including a crocodile-like animal (e.g. the phytosaur Rutiodon), or an ornithopod dinosaur, although later osteological comparisons support Lull's hypothesis that the track maker was indeed a prosauropod.[2][4]

Paleoenvironment

Otozoum grandcombensis from the Late Triassic ‘Grès supérieurs et Argilites bariolées’ Formation lived in a wide flood plain which also served as a habitat for theropod Grallator andeolensis.[2]

See also

References

- S. G. Lucas, M. G. Lockley, A. P. Hunt, L. H. Tanner. 2006. "Biostratigraphic significance of tetrapod footprints from the Triassic-Jurassic Wingate Sandstone on the Colorado Plateau". In J. D. Harris, S. G. Lucas, J. A. Spielmann, M. G. Lockley, A. R. C. Milner, & J. I. Kirkland (eds.), The Triassic-Jurassic Terrestrial Transition. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 37: 109-117

- G. Gand, M. Vianey-Liaud, G. Demathieu and J. Garric (2000). "Deux nouvelles traces de pas de Dinosaures du Trias supérieur de la bordure cévenole (la Grand-Combe, Sud-Est de la France) [New upper triassic dinosaur footprints from la Bordure cévenole' (La Grand-Combe, SE of France)]". Geobios. 33 (5): 599-624. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(00)80033-9.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hitchcock, Edward, 1847, "Description of two new species of fossil footmarks found in Massachusetts and Connecticut, or of the animals that made them", American Journal of Science and Arts Series 2, 4(3): 46-57

- Rainforth, E. C. (2003). "Revision and re-evaluation of the Early Jurassic dinosaurian ichnogenus Otozoum". Palaeontology. 46 (4): 803–838. Bibcode:2003Palgy..46..803R. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00320.

Further reading

- Martin Lockley (2001). The Eternal Trail: A Tracker Looks at Evolution. Basic Books. ISBN 0-7382-0362-9..

External links

- "Otozoum". Biology Online. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.