Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine

The Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‑19 vaccine, sold under the brand names Covishield[31] and Vaxzevria[1][32] among others, is a viral vector vaccine for prevention of COVID-19. Developed in the United Kingdom by Oxford University and British-Swedish company AstraZeneca,[33][34][35] using as a vector the modified chimpanzee adenovirus ChAdOx1.[36] The vaccine is given by intramuscular injection. Studies carried out in 2020 showed that the efficacy of the vaccine is 76.0% at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 beginning at 22 days following the first dose, and 81.3% after the second dose.[37] A study in Scotland found that, for symptomatic COVID-19 infection after the second dose, the vaccine is 81% effective against the Alpha variant (lineage B.1.1.7), and 61% against the Delta variant (lineage B.1.617.2).[38]

A vial of COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Vaccine type | Viral vector |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Vaxzevria,[1] Covishield[2][3] |

| Other names | AZD1222,[4][5] ChAdOx1 nCoV-19,[6] ChAdOx1-S,[7] COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca,[8][9] AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine,[10] AZD2816[11] |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

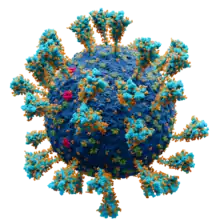

Scientifically accurate atomic model of the external structure of SARS-CoV-2. Each "ball" is an atom. |

|

|

|

The vaccine is stable at refrigerator temperatures and has a good safety profile, with side effects including injection-site pain, headache, and nausea, all generally resolving within a few days.[39][40] More rarely, anaphylaxis may occur; the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has 268 reports out of some 21.2 million vaccinations as of 14 April 2021.[40] In very rare cases (around 1 in 100,000 people) the vaccine has been associated with an increased risk of blood clots when in combination with low levels of blood platelets (Embolic and thrombotic events after COVID-19 vaccination).[41][42][1] According to the European Medicines Agency as of 4 April 2021, a total of 222 cases of extremely rare blood clots had been recorded among 34 million people who had been vaccinated in the European Economic Area (a percentage of 0.0007%).[43]

On 30 December 2020, the vaccine was first approved for use in the UK vaccination programme,[26][44][45] and the first vaccination outside of a trial was administered on 4 January 2021.[46] The vaccine has since been approved by several medicine agencies worldwide, such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA),[1][29] and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (provisional approval in February 2021),[7][47] and was approved for an Emergency Use Listing by the World Health Organization (WHO).[48] As of January 2022, more than 2.5 billion doses of the vaccine have been released to more than 170 countries worldwide.[49] Some countries have limited its use to elderly people at higher risk for severe COVID-19 illness due to concerns over the very rare side effects of the vaccine in younger individuals.[50]

Medical uses

The Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‑19 vaccine is used to provide protection against infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus in order to prevent COVID-19 in adults aged 18 years and older.[1] The medicine is administered by two 0.5 ml (0.017 US fl oz) doses given by intramuscular injection into the deltoid muscle (upper arm). The initial course consists of two doses with an interval of 4 to 12 weeks between doses. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends an interval of 8 to 12 weeks between doses for optimal efficacy.[51]

As of August 2021, there is no evidence that a third booster dose is needed to prevent severe disease in healthy adults.[51][52]

Effectiveness

Preliminary data from a study in Brazil with 61 million individuals from 18 January to 30 June 2021 indicate that the effectiveness against infection, hospitalization and death is similar between most age groups, but protection against all these outcomes is significantly reduced in those aged 90 or older, attributable to immunosenescence.[53]

A vaccine is generally considered effective if the estimate is ≥50% with a >30% lower limit of the 95% confidence interval.[54] Effectiveness is generally expected to slowly decrease over time.[55]

| Doses | Severity of illness | Delta | Alpha | Gamma | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic | 18% (9–25%)[38] | 37% (32–42%)[38] | 33% (32–34%)[53] | Not reported |

| Symptomatic | 33% (23–41%)[38] | 39% (32–45%)[38] | 33% (26–40%)[56] | Not reported | |

| Hospitalization | 71% (51–83%)[upper-alpha 1] | 76% (61–85%)[upper-alpha 1] | 52% (50–53%)[53] | Not reported | |

| 2 | Asymptomatic | 60% (53–66%)[38] | 73% (66–78%)[38] | 70% (69–71%)[53] | Not reported |

| Symptomatic | 61% (51–70%)[38] | 81% (72–87%)[38] | 78% (69–84%)[56] | 10% (−77 to 55%)[upper-alpha 2] | |

| Hospitalization | 92% (75–97%)[upper-alpha 1] | 86% (53–96%)[upper-alpha 1] | 87% (85–88%)[53] | Not reported |

Preliminary data suggest that the initial two-dose regimen is not effective against symptomatic disease caused by the Omicron variant from the 15th week onwards.[60] A regimen of two doses of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine followed by a booster dose of the Pfizer–BioNTech or the Moderna vaccine is initially about 60% effective against symptomatic disease caused by Omicron, then after 10 weeks the effectiveness drops to about 35% with the Pfizer–BioNTech and to about 45% with the Moderna vaccine.[61] The vaccine remains effective against severe disease, hospitalization and death.[62][63]

Contraindications

The Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine should not be administered to people who have had capillary leak syndrome.[64]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects in the clinical trials were usually mild or moderate and got better within a few days after vaccination.[1]

Vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, swelling, redness at the injection site and low levels of blood platelets occurred in less than 1 in 10 people.[1] Enlarged lymph nodes, decreased appetite, dizziness, sleepiness, sweating, abdominal pain, itching and rash occurred in less than 1 in 100 people.[1]

An increased risk of the rare and potentially fatal thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) has been associated with mainly younger female recipients of the vaccine.[65][66][67][68] Analysis of VigiBase reported embolic and thrombotic events after vaccination with Oxford–AstraZeneca, Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, found a temporally related incidence of 0.21 cases per 1 million vaccinated-days.[69]

Anaphylaxis and other allergic reactions are known side effects of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.[1][70] The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has assessed 41 cases of anaphylaxis from around 5 million vaccinations in the United Kingdom.[70][71]

Capillary leak syndrome is a possible side effect of the vaccine.[64]

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) listed Guillain-Barré syndrome as a very rare side effect of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and added a warning in the product information.[72]

Additional side effects include tinnitus (persistent ringing in the ears), paraesthesia (unusual feeling in the skin, such as tingling or a crawling sensation), and hypoaesthesia (decreased feeling or sensitivity, especially in the skin).[73]

Pharmacology

The Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine is a viral vector vaccine containing a modified, replication-deficient chimpanzee adenovirus ChAdOx1,[36] containing the full‐length codon‐optimised coding sequence of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein along with a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) leader sequence.[74][75] The adenovirus is called replication-deficient because some of its essential genes required for replication were deleted and replaced by a gene coding for the spike protein. However, the HEK 293 cells used for vaccine manufacturing, express several adenoviral genes, including the ones required for the vector to replicate.[76][77][78] Following vaccination, the adenovirus vector enters the cells and releases its genes, in the form of DNA, which are transported to the cell nucleus; thereafter, the cell's machinery does the transcription from DNA into mRNA and the translation into spike protein.[79] The approach to use adenovirus as a vector to deliver spike protein is similar to the approach used by the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine and the Russian Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine.[80][81]

The protein of interest is the spike protein, a protein on the exterior of the virus that enables SARS-type coronaviruses to enter cells through the ACE2 receptor.[82] Following vaccination, the production of coronavirus spike protein within the body will cause the immune system to attack the spike protein with antibodies and T-cells if the virus later enters the body.[4]

Manufacturing

_2021_C.jpg.webp)

To manufacture the vaccine the virus is propagated on HEK 293 cell lines and then purified multiple times to completely remove the cell culture.[83]

The vaccine costs around US$3 to US$4 per dose to manufacture.[39] On 17 December 2020, a tweet by the Belgian Budget State Secretary revealed that the European Union (EU) would pay €1.78 (US$2.16) per dose, The New York Times suggesting the lower price might relate to factors including investment in vaccine production infrastructure by the EU.[84]

As of March 2021 the vaccine active substance (ChAdOx1-SARS-COV-2) is being produced at several sites worldwide,[85] with AstraZeneca claiming to have established 25 sites in 15 countries.[86] The UK sites are Oxford and Keele with bottling and finishing in Wrexham.[85] Other sites include the Serum Institute of India at Pune.[85] The Halix site at Leiden was approved by the EMA on 26 March 2021, joining three other sites approved by the EU.[87]

History

The vaccine arose from a collaboration between Oxford University's Jenner Institute and Vaccitech, a private company spun off from the university, with financing from Oxford Sciences Innovation, Google Ventures, and Sequoia Capital, among others.[88] The first batch of the COVID-19 vaccine produced for clinical testing was developed by Oxford University's Jenner Institute and the Oxford Vaccine Group in collaboration with Italian manufacturer Advent Srl located in Pomezia.[89] The team is led by Sarah Gilbert, Adrian Hill, Andrew Pollard, Teresa Lambe, Sandy Douglas and Catherine Green.[90][89]

Early development

In February 2020, the Jenner Institute agreed a collaboration with the Italian company Advent Srl for the production of a batch of 1,000 doses of a vaccine candidate for clinical trials.[91] Originally, Oxford intended to donate the rights to manufacture and market the vaccine to any drugmaker who wanted to do so, but after the Gates Foundation urged Oxford to find a large company partner to get its COVID-19 vaccine to market, the university backed off of this offer in May 2020.[92][93][94] The UK government then encouraged Oxford to work with AstraZeneca, a company based in Europe, instead of Merck & Co., a US-based company (The Guardian reported the initial partner was the German-based Merck Group instead).[95] Government ministers also had concerns that a vaccine manufactured in the US would not be available in the UK, according to anonymous sources in The Wall Street Journal. Financial considerations at Oxford and spin-out companies may have also played a part in the decision to partner with AstraZeneca.[96][97]

An initially not-for-profit licensing agreement was signed between the university and AstraZeneca PLC, in May 2020, with 1 billion doses of potential supply secured, with the UK reserving access to the initial 100 million doses. Furthermore, the US reserved 300 million doses, as well as the authority to perform Phase III trials in the US. The collaboration was also granted £68m of UK government funding, and US$1.2bn of US government funding, to support the development of the vaccine.[98] In June 2020, the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) confirmed that the third phase of trials for the vaccine would begin in July 2020.[99] On 4 June, AstraZeneca announced that the COVAX program for equitable vaccine access managed by the WHO and financed by CEPI and GAVI had spent $750m to secure 300 million doses of the vaccine to be distributed to low-income or under-developed countries.[100][101]

Preliminary data from a study that reconstructed funding for the vaccine indicates that funding was at least 97% public, almost all from UK government departments, British and American scientific institutes, the European Commission and charities.[102]

Clinical trials

In July 2020, AstraZeneca partnered with IQVIA to accelerate the timeframe for clinical trials being planned or conducted in the US.[103] On 31 August, AstraZeneca announced that it had begun enrolment of adults for a US-funded, 30,000-subject late-stage study.[104]

Clinical trials for the vaccine candidate were halted worldwide on 8 September, as AstraZeneca investigated a possible adverse reaction which occurred in a trial participant in the UK.[105][106] Trials were resumed on 13 September after AstraZeneca and Oxford, along with UK regulators, concluded it was safe to do so.[107] AstraZeneca was later criticised for refusing to provide details about potentially serious neurological side effects in two trial participants who had received the experimental vaccine in the UK.[108] While the trials resumed in the UK, Brazil, South Africa, Japan[109] and India, the US did not resume clinical trials of the vaccine until 23 October.[110] This was due to a separate investigation by the Food and Drug Administration surrounding a patient illness that triggered a clinical hold, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar.[111]

The results of the COV002 phase II/III trial showed that immunity lasts for at least one year after a single dose.[112]

Results of Phase III trial

On 23 November 2020, the first interim data was released by Oxford University and AstraZeneca from the vaccine's ongoing Phase III trials.[4][113] The interim data reported a 70% efficacy, based on combined results of 62% and 90% from different groups of participants who were given different dosages. The decision to combine results from two different dosages was met with criticism from some who questioned why the results were being combined.[114][115][116] AstraZeneca responded to the criticism by agreeing to carry out a new multi-country trial using the lower dose, which had led to the 90% claim.[117]

The full publication of the interim results from four ongoing Phase III trials on 8 December allowed regulators and scientists to begin evaluating the vaccine's efficacy.[118] The December report showed that at 21 days after the second dose and beyond, there were no hospitalisations or severe disease in those who received the vaccine, compared to 10 cases in the control groups. The rate of serious adverse events was balanced between the active and control groups, which suggested that the active vaccine did not pose safety concerns beyond a rate experienced in the general population. One case of transverse myelitis was reported 14 days after the second-dose was administered as being possibly related to vaccination, with an independent neurological committee considering the most likely diagnosis to be of an idiopathic, short-segment, spinal cord demyelination. The other two cases of transverse myelitis, one in the vaccine group and the other in the control group, were considered to be unrelated to vaccination.[118]

A subsequent analysis, published on 19 February 2021, showed an efficacy of 76.0% at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 beginning at 22 days following the first dose, increasing to 81.3% when the second dose is given 12 weeks or more after the first.[37] However, the results did not show any protection against asymptomatic COVID-19 following only one dose.[37] Beginning 14 days following timely administration of a second dose, with different duration from the first dose depending on trials, the results showed 66.7% efficacy at preventing symptomatic infection, and the UK arm (which evaluated asymptomatic infections in participants) was inconclusive as to the prevention of asymptomatic infection.[37] Efficacy was higher at greater intervals between doses, peaking at around 80% when the second dose was given at 12 weeks or longer after the first.[37] Preliminary results from another study with 120 participants under 55 years of age showed that delaying the second dose by up to 45 weeks increases the resulting immune response and that a booster (third) dose given at least six months later produces a strong immune response. A booster dose may not be necessary, but it alleviates concerns that the body would develop immunity to the vaccine's viral vector, which would reduce the potency of annual inoculations.[119]

On 22 March 2021, AstraZeneca released interim results from the phase III trial conducted in the US that showed efficacy of 79% at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 and 100% efficacy at preventing severe disease and hospitalisation.[120] The next day, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) published a statement countering that those results may have relied on "outdated information" that may have provided an incomplete view of the efficacy data.[121][122][123][124] AstraZeneca later revised its efficacy claim to be 76% after further review of the data.[125] On 29 September 2021, AstraZeneca shows of 74% efficacy rate in the US trial.[126][127]

Single dose effectiveness

A study on the effectiveness of a first dose of the Pfizer–BioNTech or Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19 related hospitalisation in Scotland was based on a national prospective cohort study of 5.4 million people. Between 8 December 2020 and 15 February 2021, 1,137,775 participants were vaccinated in the study, 490,000 of whom were given the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine. The first dose of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine was associated with a vaccine effect of 94% for COVID-19-related hospitalisation at 28–34 days post-vaccination. Combined results (all vaccinated participants, whether Pfizer–BioNTech or Oxford–AstraZeneca) showed a significant vaccine effect for prevention of COVID-19-related hospitalisation, which was comparable when restricting the analysis to those aged ≥80 years (81%). The majority of the participants over the age of 65 were given the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine.[128]

Nasal spray

On 25 March 2021, the University of Oxford announced the start of a phase I clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of an intranasal spray method.[129][130]

Approvals

Full authorization

Emergency authorization

Allowed for travel

Usage stopped |

The first country to issue a temporary or emergency approval for the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine was the UK. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) began a review of efficacy and safety data on 27 November 2020,[131] followed by approval for use on 30 December 2020, becoming the second vaccine approved for use in the national vaccination programme.[132] The BBC reported that the first person to receive the vaccine outside of clinical trials was vaccinated on 4 January 2021.[46]

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) began review of the vaccine on 12 January 2021, and stated in a press release that a recommendation could be issued by the agency by 29 January, followed by the European Commission deciding on a conditional marketing authorisation within days.[133] On 29 January 2021, the EMA recommended granting a conditional marketing authorisation for AZD1222 for people 18 years of age and older,[1][28] and the recommendation was accepted by the European Commission the same day.[29][134] Prior to approval across the EU, the Hungarian regulator unilaterally approved the vaccine instead of waiting for EMA approval.[135] In October 2022, the conditional marketing authorisation was converted to a standard one.[27]

On 30 January 2021, the Vietnamese Ministry of Health approved the AstraZeneca vaccine for use, becoming the first vaccine to be approved in Vietnam.[136] The vaccine has since been approved by a number of non-EU countries, including Argentina,[137] Bangladesh,[138] Brazil,[139] the Dominican Republic,[140] El Salvador,[141] India,[142][143] Israel,[144] Malaysia,[145] Mexico,[146] Nepal,[147] Pakistan,[148] the Philippines,[149] Sri Lanka,[150] and Taiwan[151] regulatory authorities for emergency usage in their respective countries.

South Korea granted approval of the AstraZeneca vaccine on 10 February 2021, thus becoming the first vaccine to be approved for use in that country. The regulator recommended the two-shot regimen be used in all adults, including the elderly, noting that consideration is needed when administering the vaccine to individuals over 65 years of age due to limited data from that demographic in clinical trials.[152][153] On the same day, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued interim guidance and recommended the AstraZeneca vaccine for all adults, its Strategic Advisory Group of Experts also having considered use where variants were present and concluded there was no need not to recommend it.[154]

In February 2021, the government and regulatory authorities in Australia (16 February 2021)[7][8] and Canada (26 February 2021) granted approval for temporary use of the vaccine.[155]

On 19 November 2021, the vaccine was approved for use in Canada.[20]

South Africa

On 7 February 2021, the vaccine rollout in South Africa was suspended. Researchers from the University of the Witwatersrand released interim, non-peer-reviewed data that suggested the AstraZeneca vaccine provided minimal protection against mild or moderate disease infection among young people.[156][157] The BBC reported on 8 February 2021 that Katherine O'Brien, director of immunisation at the WHO, felt it was "really plausible" the AstraZeneca vaccine could have a "meaningful impact" on the Beta variant (lineage B.1.351), particularly in preventing serious illness and death.[158] The same report also indicated the Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England Jonathan Van-Tam said the Witwatersrand study did not change his opinion that the AstraZeneca vaccine was "rather likely" to have an effect on severe disease from the Beta variant.[158] The South African government subsequently cancelled the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine.[159]

European Union

On 3 March 2021, Austria suspended the use of one batch of vaccine after two people had blood clots after vaccination, one of whom died.[160] In total, four cases of blood clots have been identified in the same batch of 1 million doses.[160] Although no causal link with vaccination has been shown,[161] several other countries, including Denmark,[162] Norway,[162] Iceland,[162] Bulgaria,[163] Ireland,[164] Italy,[161] Spain,[165] Germany,[166] France, the Netherlands[167] and Slovenia[168] also halted the vaccine rollout over the following days while waiting for the EMA to finish a safety review triggered by the cases.

In April 2021, the EMA concluded its safety review and concluded that unusual blood clots with low blood platelets should be listed as very rare side effects while reaffirming the overall benefits of the vaccine.[43][169][70][71] Following this announcement EU countries have resumed use of the vaccine with some limiting its use to elderly people at higher risk for severe COVID-19 illness.[50][170]

On 11 March 2021, the Norwegian government temporarily suspended the vaccine's use, awaiting more information regarding potential adverse effects. Then, on 15 April, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health recommended to the government to permanently suspended vaccination with AstraZeneca due to the "rare but severe incidents with low platelet counts, blood clots, and haemorrhages," since in the case of Norway, "the risk of dying after vaccination with the AstraZeneca vaccine would be higher than the risk of dying from the disease, particularly for younger people."[171] At the same time, the Norwegian government announced their decision to wait for a final decision and to establish an expert group to provide a broader assessment on the safety of the AstraZeneca and Janssen vaccines.[172][173] On 10 May, the expert committee also recommended suspending the use of both vaccines.[174] Finally, on 12 May —two months after the initial suspension— the Prime Minister of Norway announced that the government decided to completely remove the AstraZeneca vaccine from the Norwegian Coronavirus Immunisation Programme, and people who have had the first will be offered another coronavirus vaccine for their second dose.[175][176][171]

On 30 March 2021, the German Ministry of Health announced that the use of the vaccine in people aged 60 and below should be the result of a recipient-specific discussion,[177] and that younger patients could still be given the AstraZeneca vaccine, but only "at the discretion of doctors, and after individual risk analysis and thorough explanation".[177]

On 14 April, the Danish Health Authority suspended use of the vaccine.[178][179][180][181] The Danish Health Authority said that it had other vaccines available, and that the next target groups being a lower-risk population had to be "[weighed] against the fact that we now have a known risk of severe adverse effects from vaccination with AstraZeneca, even if the risk in absolute terms is slight."[181]

A 2021 study found that the decisions to suspend the vaccine led to increased vaccine hesitancy across the West, even in countries that did not suspend the vaccine.[182]

In October 2022, the conditional marketing authorisation was converted to a standard one.[27]

Despite the continued authorsation, most EU countries stopped the administration of the vaccine by end of 2021. After an initial quick uptake, the number of doses administered remained at 67 Million since October 2021.[183]

Canada

On 29 March 2021, Canada's National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommended that distribution of the vaccine be suspended for patients below the age of 55; NACI chairwoman Caroline Quach-Thanh stated that the risk of blood clots was higher in younger patients, and that NACI needed to "evolve" its recommendations as new data becomes available. Most Canadian provinces subsequently announced that they would follow this guidance.[184][185][186] As of 20 April 2021 there had been three confirmed cases of blood clotting tied to the vaccine in Canada, out of over 700,000 doses administered in the country.[187][188][189]

Beginning 18 April, amid a major third wave of the virus, several Canadian provinces announced that they would backtrack on the NACI recommendation and extend eligibility for the AstraZeneca vaccine to residents as young as 40 years old, including Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, and Saskatchewan. Quebec also extended eligibility to residents 45 and older.[190][191][192] The NACI guidance is a recommendation which does not affect the formal approval of the vaccine by Health Canada for all adults over 18; it stated on 14 April that it had updated its warnings on the vaccine as part of an ongoing review, but that "the potential risk of these events is very rare, and the benefits of the vaccine in protecting against COVID-19 outweigh its potential risks."[193]

On 23 April, citing the current state of supplies for mRNA-based vaccines and new data, NACI issued a recommendation that the vaccine can be offered to patients as young as 30 years old if benefits outweigh the risks, and the patient "does not wish to wait for an mRNA vaccine".[194]

Beginning 11 May, multiple provinces announced that they would suspend use of the AstraZeneca vaccine once again, citing either supply issues or the blood clotting risk. Some provinces stated that they planned to only use the AstraZeneca vaccine for outstanding second doses.[195][196][197] On 1 June, NACI issued guidance, citing the safety concerns as well as European studies showing an improved antibody response, recommending that an mRNA vaccine be administered as a second dose to patients that had received the AstraZeneca vaccine as their first dose.[198]

Indonesia

In March 2021, Indonesia halted the rollout of the vaccine while awaiting more safety guidance from the World Health Organization,[199] and then resumed using the vaccine on 19 March.[200]

Australia

In June 2021, Australia revised its recommendations for the rollout of the vaccine, recommending that the Pfizer Comirnaty vaccine be used for people aged under 60 years if the person has not already received a first dose of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. The AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine can still be used in people aged under 60 years where the benefits are likely to outweigh the risks for that person, and the person has made an informed decision based on an understanding of the risks and benefits in consultation with a medical professional.[201]

Malaysia

After initially approving the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine, Malaysian health authorities removed the vaccine from the country's mainstream vaccination programme due to public concerns about its safety.[202] The AstraZeneca vaccines will be distributed in designated vaccination centres, and the public can register for the vaccine on a voluntary basis. All 268,800 doses of the initial batch of the vaccine were fully booked in three and a half hours after the registration opened for residents of the state of Selangor and the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur.[203] A second batch of 1,261,000 doses was offered to residents of the states of Selangor, Penang, Johore, Sarawak, and the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur. A total of 29,183 doses were reserved for previously waitlisted registrants, and 275,208 doses were taken up by senior citizens during a grace 3-day period. The remaining 956,609 doses were then offered to those aged 18 and above, and was completely booked within an hour.[204]

Safety review

In March 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) stated that there is no indication that vaccination has been the cause of the observed clotting issues, which were not listed as side effects of the vaccine.[160][205] At the time, according to the EMA, the number of thromboembolic events in vaccinated people was no higher than that seen in the general population.[205] As of 11 March 2021, 30 cases of thromboembolic events had been reported among the almost 5 million people vaccinated in the European Economic Area.[205] The UK's MHRA also stated that after more than 11 million doses administered, it had not been confirmed that the reported blood clots were caused by the vaccine and that vaccinations would not be stopped.[206] On 12 March 2021 the WHO stated that a causal relationship had not been shown and that vaccinations should continue.[207] AstraZeneca confirmed on 14 March 2021 that after examining over 17 million people who have been vaccinated with the vaccine, no evidence of an increased risk of blood clots in any particular country was found.[208] The company reported that as of 8 March 2021, across the EU and UK, there had been 15 events of deep vein thrombosis and 22 events of pulmonary embolism reported among those given the vaccine, which is much lower than would be expected to occur naturally in a general population of that size.[208]

In March 2021, the German Paul-Ehrlich Institute (PEI) reported that out of 1.6 million vaccinations, seven cases of cerebral vein thrombosis in conjunction with a deficiency of blood platelets had occurred.[209] According to the PEI, the number of cases of cerebral vein thrombosis after vaccination was statistically significantly higher than the number that would occur in the general population during a similar time period.[209] These reports prompted the PEI to recommend a temporary suspension of vaccinations until the EMA had completed their review of the cases.[210]

The World Health Organization (WHO) issued a statement on 17 March, regarding the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine safety signals, and still considers the benefits of the vaccine to outweigh its potential risks, further recommending that vaccinations continue.[211] On 18 March, the EMA announced that out of the around 20 million people who had received the vaccine, general blood clotting rates were normal, but that it had identified seven cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and eighteen cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.[212] A causal link with the vaccine was not proven, but the EMA said it would conduct further analysis and recommended informing people eligible for the vaccine of the fact that the possibility it may cause rare clotting problems had not been disproven.[212] The EMA confirmed that the vaccine's benefits outweighed the risks.[212] On 25 March, the EMA released updated product information.[213][42][214]

According to the EMA, 100,000 cases of blood clots occur naturally each month in the EU, and the risk of blood clots was not statistically higher in the vaccinated population. The EMA noted that COVID-19 itself causes an increased risk of the development of blood clots, and as such the vaccine would lower the risk of the formation of blood clots even if the 15 cases' causal link were to be confirmed.[215] Italy resumed vaccinations after the EMA's statement,[216] with most of the remaining European countries following suit and resuming their AstraZeneca inoculations shortly thereafter.[217] To reassure the public of the vaccine's safety, the British and French Prime Ministers, Boris Johnson and Jean Castex, had themselves vaccinated with it in front of the media shortly after the restart of the AstraZeneca vaccination campaigns in the EU.[218]

In April 2021, the EMA issued its direct healthcare professional communication (DHPC) about the vaccine.[219] The DHPC indicated that a causal relationship between the vaccine and blood clots (thrombosis) in combination with low blood platelets (thrombocytopenia) was plausible and identified it as a very rare side effect of the vaccine.[219] According to the EMA these very rare adverse events occur in around 1 out of 100,000 vaccinated people.[41]

Efficacy against variants

A study published in April 2021 by researchers from the COVID-19 Genomics United Kingdom Consortium, the AMPHEUS Project, and the Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Trial Group indicated the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine showed somewhat reduced efficacy against infection with the Alpha variant (lineage B.1.1.7), with 70.4% efficacy in absolute terms against Alpha versus 81.5% against other variants.[220] Despite this, the researchers concluded that the vaccine remained effective at preventing symptomatic infection from this variant and that vaccinated individuals infected symptomatically typically had shorter duration of symptoms and less viral load, thereby reducing the risk of transmission.[221] Following the identification of notable variants of concern, concern arose that the E484K mutation, present in the Beta and Gamma variants (lineages B.1.351 and P.1), could evade the protection given by the vaccine.[222] In February 2021, the collaboration was working to adapt the vaccine to target these variants,[223] with the expectation that a modified vaccine would be available "in a few months" as a "booster" given to people who had already completed the two-dose series of the original vaccine.[224]

In June 2021, AstraZeneca published a press release confirming undergoing Phase II/III trials of an AZD2816 COVID-19 variant vaccine candidate. The new vaccine would be based on the current Vaxzevria adenoviral vector platform but modified with spike proteins based on the Beta (B.1.351 lineage) variant.[11] Phase II/III trials saw 2849 volunteers participating from UK, South Africa, Brazil and Poland with parallel dosing of both the current Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and the variant vaccine candidate.[225][11] By September 2021, AZD2816 vaccine candidate is still undergoing Phase II/III trials with intent to switch to this vaccine if approved by government regulators. Particularly the government of Thailand, with delivery of additional 60 million doses of AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine agreed for 2022.[226]

Heterologous prime-boost vaccination

In December 2020, a clinical trial was registered to examine a heterologous prime-boost vaccination course consisting of one dose of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine followed by Sputnik Light based on the Ad26 vector 29 days later.[227]

After suspensions due to rare cases of blood clots in March 2021, Canada and several European countries recommended receiving a different vaccine for the second dose. Despite the lack of clinical data on the efficacy and safety of such heterologous combinations, some experts believe that doing so may boost immunity, and several studies have begun to examine this effect.[228][229]

In June 2021, preliminary results from a study of 463 participants showed that a heterologous prime-boost vaccination course consisting of one dose of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine followed by one dose of the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine produced the strongest T cell activity and an antibody level almost as high as two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. The reversal of the order resulted in T cell activity at half the potency and one-seventh the antibody levels, the latter still five times higher than two doses of Oxford–AstraZeneca. The lowest T cell activity was observed in homologous courses, when both doses were of the same vaccine.[230]

In July 2021, a study of 216 participants found that a heterologous prime-boost vaccination course consisting of one dose of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine followed by one dose of the Moderna vaccine produced a similar level of neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses with increased spike-specific cytotoxic T cells compared to a homologous course consisting of two doses of the Moderna vaccine.[231]

Society and culture

The Oxford University and AstraZeneca collaboration was seen as having the potential as being a low-cost vaccine with no onerous storage requirements.[232] A series of events including a deliberate undermining of the AstraZeneca vaccine for geopolitical purposes by both the EU and EU member states including miscommunication, reports of supply difficulties (responsibility of which were due to the EU mis-handling vaccine procurement)[233] misleading reports of inefficacy and adverse effects[234] as well as the high-profile European Commission–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine dispute, have been a public relations disaster for both Brussels and member states,[235][236] and in the opinion of one academic has led to increased vaccine hesitancy.[232]

The vaccine is a key component of the WHO backed COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) program,[232] with the WHO, the EMA, and the MHRA continuing to state that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh any possible side effects.[237]

About 69 million doses of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine were administered in the EU/EEA from authorization to 26 June 2022.[73]

Economics

| Country | Date | Doses |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 17 May 2020[lower-alpha 1] | 100 million[238][239] |

| United States | 21 May 2020 | 300 million[240] |

| COVAX (WHO) | 4 June 2020 | 300 million[241] |

| 29 September 2020 | 100 million[242] | |

| Egypt | 22 June 2020 | Unknown[243] |

| Japan | 8 August 2020 | 120 million[244] |

| Australia | 19 August 2020 | 25 million[245] |

| European Union[lower-alpha 2] | 27 August 2020[lower-alpha 3] | 400 million[246][247][248][249] |

| Canada | 25 September 2020 | 20 million[250][251] |

| Switzerland | 16 October 2020 | 5.3 million[252][253] |

| Bangladesh | 5 November 2020 | 30 million[254] |

| Thailand | 27 November 2020 | 26 million[255] |

| Philippines | 27 November 2020 | 2.6 million[256] |

| South Korea | 1 December 2020 | 20 million[257] |

| South Africa | 7 January 2021 | 1 million[lower-alpha 4][258] |

| ||

Agreements for access to vaccines began being signed in May 2020, with the UK having priority for the first 100 million doses if trials proved successful, with the final agreement being signed at the end of August.[238][239][259][260]

On 21 May 2020, AstraZeneca agreed to provide 300 million doses to the US for US$1.2 billion, implying a cost of US$4 per dose.[240] An AstraZeneca spokesman said the funding also covers development and clinical testing.[261] It also reached a technology transfer agreement with the Mexican and Argentinean governments and agreed to produce at least 400 million doses to be distributed throughout Latin America. The active ingredients would be produced in Argentina and sent to Mexico to be completed for distribution.[262] In June 2020, Emergent BioSolutions signed a US$87 million deal to manufacture doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine specifically for the US market. The deal was part of the Trump administration's Operation Warp Speed initiative to develop and rapidly scale production of targeted vaccines before the end of 2020.[263] Catalent would be responsible for the finishing and packaging process.[264]

On 4 June 2020, the WHO's COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) facility made initial purchases of 300 million doses from the company for low- to middle-income countries.[241] Also, AstraZeneca and Serum Institute of India reached a licensing agreement to independently supply 1 billion doses of the Oxford University vaccine to middle- and low-income countries, including India.[265][266] Later in September, funded by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the COVAX program secured an additional 100 million doses at US$3 per dose.[242]

On 27 August 2020, AstraZeneca concluded an agreement with the EU, to supply up to 400 million doses to all EU and select European Economic Area (EEA) member states.[246][247] The European Commission took over negotiations started by the Inclusive Vaccines Alliance, a group made up of France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, in June 2020.[267][268][269]

On 5 November 2020, a tripartite agreement was signed between the government of Bangladesh, the Serum Institute of India, and Beximco Pharma of Bangladesh. Under the agreement Bangladesh ordered 30 million doses of Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine from Serum through Beximco for $4 per shot.[254] On the other hand, Indian government has given 3.2 million doses to Bangladesh as a gift which were also produced by Serum. But Serum supplied only 7 million doses from the tripartite agreement in the first two months of the year.[270] Bangladesh was supposed to receive 5 million doses per month but not received shipments in March and April.[271] As a result, rollout of vaccine has been disrupted by supply shortfalls.[271] The situation became complicated when the second dose of 1.3 million citizens is uncertain as India halts exports.[272] Not getting the second dose at the right time is likely to reduce the effectiveness of the vaccination program. In addition, several citizens of Bangladesh have expressed doubts about its effectiveness and safety.[270] Bangladesh is looking for alternative vaccine sources because India isn't supplying the vaccine according to the timeline of the deal.[273]

Thailand's agreement in November 2020 for 26 million doses of vaccine[255] would cover 13 million people,[274] approximately 20% of the population, with the first lot expected to be delivered at the end of May.[275][276][277] The public health minister indicated the price paid was $5 per dose;[278] AstraZeneca (Thailand) explained in January 2021 after a controversy that the price each country paid depended on production cost and differences in supply chain, including manufacturing capacity, labour and raw material costs.[279] In January 2021, the Thai cabinet approved further talks on ordering another 35 million doses,[280] and the Thai FDA approved the vaccine for emergency use for 1 year.[281][282] Siam Bioscience, a company owned by Vajiralongkorn, will receive technological transfer[283] and has the capacity to manufacture up to 200 million doses a year for export to ASEAN.[284]

Also in November, the Philippines agreed to buy 2.6 million doses,[256] reportedly worth around ₱700 million (approximately US$5.60 per dose).[285] In December 2020, South Korea signed a contract with AstraZeneca to secure 20 million doses of its vaccine, reportedly equivalent in worth to those signed by Thailand and the Philippines,[257] with the first shipment expected as early as January 2021. As of January 2021, the vaccine remains under review by the South Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.[286][287] AstraZeneca signed a deal with South Korea's SK Bioscience to manufacture its vaccine products. The collaboration calls for the SK affiliate to manufacture AZD1222 for local and global markets.[288]

On 7 January 2021, the South African government announced that they had secured an initial 1 million doses from the Serum Institute of India, to be followed by another 500,000 doses in February,[258] however the South African government subsequently cancelled the use of the vaccine, selling its supply to other African countries, and switched its vaccination program to use the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine.[159][289]

On 22 January 2021, AstraZeneca announced that in the event the European Union approved the COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca, initial supplies would be lower than expected due to production issues at Novasep in Belgium. Only 31 million of the previously predicted 80 million doses would be delivered to the EU by March 2021.[290] In an interview with Italian newspaper La Repubblica, AstraZeneca's CEO Pascal Soriot said the delivery schedule for the doses in the EU was two months behind schedule. He mentioned low yield from cell cultures at one large-scale European site.[291] Analysis published in The Guardian also identified an apparently low yield from bioreactors in the Belgium plant and noted the difficulties in setting up this form of process, with variable yields often occurring.[292] As a result, the EU imposed export controls on vaccine doses; controversy erupted as to whether doses were being diverted to the UK and whether deliveries to Northern Ireland would be disrupted.[293]

On 24 February 2021, a shipment of the vaccine to Accra, Ghana, via COVAX made it the first country in Africa to receive vaccines via the initiative.[294]

In early 2021, the Bureau for Investigative Journalism found that South Africa had paid double the rate for the European Commission, while Uganda paid triple.[295][296]

According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency data, Oxford received a US$176 million windfall on vaccine in the 2021-22 academic year.[297]

Brand names

The vaccine is marketed under the brand name Covishield by the Serum Institute of India.[2] The name of the vaccine was changed to Vaxzevria in the European Union on 25 March 2021.[1] Vaxzevria, AstraZeneca COVID‐19 Vaccine, and COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca are manufactured by AstraZeneca.[1][2]

Research

As of February 2021, the AZD1222 development team is working on adapting the vaccine to be more effective in relation to newer SARS-CoV-2 variants; redesigning the vaccine being the relatively quick process of switching the genetic sequence of the spike protein.[298] Manufacturing set-up and a small scale trial are also required before the adapted vaccine might be available in autumn.[298]

References

- "Vaxzevria (previously COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca) EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 25 January 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- "AstraZeneca / Covishield COVID-19 vaccine: What you should know". Health Canada. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- "Already produced 40–50 million dosages of Covishield vaccine, says Serum Institute". The Hindu. 28 December 2020. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- "AZD1222 vaccine met primary efficacy endpoint in preventing COVID-19". Press Release (Press release). AstraZeneca. 23 November 2020. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine (AZD1222)" (PDF). AstraZeneca. 27 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- "AstraZeneca and Oxford University announce landmark agreement for COVID-19 vaccine". AstraZeneca (Press release). 30 April 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- "COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca PI". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- "COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "Information for Healthcare Professionals on COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 30 December 2020. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "First COVID-19 variant vaccine AZD2816 Phase II/III trial participants vaccinated" (Press release). AstraZeneca. 27 June 2021. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- "Updates to the Prescribing Medicines in Pregnancy database". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 December 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- "Summary for ARTG Entry: 349072 COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1-S) solution for injection multidose vial".

- "COVID-19 vaccine: AstraZeneca ChAdOx1-S". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- "AusPAR: ChAdOx-1-S". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 17 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- "AstraZeneca) Labelling Exemption 2021". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- "Brazil grants full approval to Oxford vaccine, orders Sputnik". Brasilia: France 24. Agence France-Presse. 12 March 2021. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- "Anvisa aprova registro da vacina da Fiocruz/AstraZeneca e de medicamento contra o coronavírus" [Anvisa approves registration of Fiocruz/AstraZeneca vaccine and drug against the coronavirus] (in Portuguese). Federal government of Brazil. Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency. 20 November 2021. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- "Regulatory Decision Summary - Vaxzevria". Health Canada. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- "AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine monograph" (PDF). AstraZeneca. 26 February 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Vaxzevria". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- "Vaxzevria (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant])". Health Canada. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- "Covishield (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant])". COVID-19 vaccines and treatments portal. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- "Vaxzevria, suspension for injection, COVID 19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1 S [recombinant]) - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- "Conditions of Authorisation for COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 30 December 2020. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "EMA recommends COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca for authorisation in the EU". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "European Commission authorises third safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19". European Commission (Press release). Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "아스트라제네카社 코로나19 백신 품목허가" [AstraZeneca's Corona 19 vaccine product license]. 식품의약품안전처 (in Korean). 10 February 2021. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- "Covishield and Covaxin: What we know about India's Covid-19 vaccines". BBC News. 4 March 2021. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- "AstraZeneca vaccine renamed 'Vaxzevria'". The Brussels Times. 30 March 2021. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Investigating a Vaccine Against COVID-19". ClinicalTrials.gov (Registry). United States National Library of Medicine. 26 May 2020. NCT04400838. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "A Phase 2/3 study to determine the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of the candidate Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19". EU Clinical Trials Register (Registry). European Union. 21 April 2020. EudraCT 2020-001228-32. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- O'Reilly P (May 2020). "A Phase III study to investigate a vaccine against COVID-19". ISRCTN (Registry). doi:10.1186/ISRCTN89951424. ISRCTN89951424.

- Voysey M, Clemens SA, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, Angus B, Baillie VL, Barnabas SL, Bhorat QE, Bibi S, Briner C, Cicconi P, Collins AM, Colin-Jones R, Cutland CL, Darton TC, Dheda K, Duncan CJ, Emary KR, Ewer KJ, Fairlie L, Faust SN, Feng S, Ferreira DM, Finn A, Goodman AL, Green CM, Green CA, Heath PT, Hill C, Hill H, Hirsch I, Hodgson SH, Izu A, Jackson S, Jenkin D, Joe CC, Kerridge S, Koen A, Kwatra G, Lazarus R, Lawrie AM, Lelliott A, Libri V, Lillie PJ, Mallory R, Mendes AV, Milan EP, Minassian AM, McGregor A, Morrison H, Mujadidi YF, Nana A, O'Reilly PJ, Padayachee SD, Pittella A, Plested E, Pollock KM, Ramasamy MN, Rhead S, Schwarzbold AV, Singh N, Smith A, Song R, Snape MD, Sprinz E, Sutherland RK, Tarrant R, Thomson EC, Török ME, Toshner M, Turner DP, Vekemans J, Villafana TL, Watson ME, Williams CJ, Douglas AD, Hill AV, Lambe T, Gilbert SC, Pollard AJ (January 2021). "Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK". Lancet. 397 (10269): 99–111. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7723445. PMID 33306989.

- Voysey M, Costa Clemens SA, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. (February 2021). "Single-dose administration and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a pooled analysis of four randomised trials". Lancet. 397 (10277): 881–891. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00432-3. PMC 7894131. PMID 33617777.

- Sheikh A, McMenamin J, Taylor B, Robertson C (14 June 2021). "SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness". The Lancet. 397 (10293). Table S4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 8201647. PMID 34139198.

- Belluz J (23 November 2020). "Why the AstraZeneca-Oxford Covid-19 vaccine is different". Vox. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Coronavirus Vaccine : Summary of Yellow Card reporting" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2021.

It is known from the clinical trials that the more common side effects for both vaccines can occur at a rate of more than one in 10 doses (for example, local reactions or symptoms resembling transient flu-like symptoms)

- "AstraZeneca's COVID-19 vaccine: benefits and risks in context". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 23 April 2021. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- "Annex 1: Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- "AstraZeneca's COVID-19 vaccine: EMA finds possible link to very rare cases of unusual blood clots with low platelets". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 7 April 2021. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- "Covid-19: Oxford-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine approved for use in UK". BBC News Online. 30 December 2020. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- "Second COVID-19 vaccine authorised by medicines regulator". GOV.UK (Press release). 30 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "Covid: Brian Pinker, 82, first to get Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine". BBC News Online. 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Vaccines undergoing evaluation". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 20 July 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2021. AstraZeneca Pty Ltd, ChAdOx1-S [recombinant], Viral vector -- Provisional determination notice -- Provisionally approved on 15 February 2021

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Vaccines" (Press release). World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "One year anniversary of UK deploying Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine". gov.uk (Press release). Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "Spain, Belgium and Italy restrict AstraZeneca Covid vaccine to older people". The Guardian. 8 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- Interim recommendations for use of the ChAdOx1-S [recombinant] vaccine against COVID-19 (AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine AZD1222, SII Covishield, SK Bioscience) (Guidance). World Health Organization. 21 April 2021. WHO/2019-nCoV/vaccines/SAGE_recommendation/AZD1222/2021.2. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- "Interim statement on COVID-19 vaccine booster doses" (Press release). World Health Organization. 10 August 2021. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Cerqueira-Silva T, Oliveira VA, Pescarini J, Júnior JB, Machado TM, Ortiz RF, et al. (25 August 2021). "The effectiveness of Vaxzevria and CoronaVac vaccines: A nationwide longitudinal retrospective study of 61 million Brazilians (VigiVac-COVID19)". Results, table S2. medRxiv 10.1101/2021.08.21.21261501v1.

- Krause P, Fleming TR, Longini I, Henao-Restrepo AM, Peto R, Dean NE, et al. (12 September 2020). "COVID-19 vaccine trials should seek worthwhile efficacy". The Lancet. 396 (10253): 741–743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31821-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7832749. PMID 32861315.

WHO recommends that successful vaccines should show an estimated risk reduction of at least one-half, with sufficient precision to conclude that the true vaccine efficacy is greater than 30%. This means that the 95% CI for the trial result should exclude efficacy less than 30%. Current US Food and Drug Administration guidance includes this lower limit of 30% as a criterion for vaccine licensure.

- Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. (May 2021). "Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection". Nature Medicine. 27 (7): 1205–1211. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 34002089. S2CID 234769053. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Hitchings MD, Ranzani OT, Dorion M, D'Agostini TL, Paula RC, Paula OF, et al. (22 July 2021). "Effectiveness of the ChAdOx1 vaccine in the elderly during SARS-CoV-2 Gamma variant transmission in Brazil". medRxiv 10.1101/2021.07.19.21260802v1.

- Stowe J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Utsi L, Simmons R, et al. (14 June 2021). Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against hospital admission with the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant (Preprint). Public Health England. Table 1. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021 – via Knowledge Hub.

- SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England, technical briefing 17 (PDF) (Briefing). Public Health England. 25 June 2021. GOV-8576. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- Madhi SA, Baillie V, Cutland CL, Voysey M, Koen AL, Fairlie L, et al. (May 2021). "Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (20): 1885–1898. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102214. PMC 7993410. PMID 33725432.

- Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 14 December 2021 (Situation report). World Health Organization. 14 December 2021. p. 11. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

This test-negative case-control study conducted in the United Kingdom found evidence that two doses of AstraZeneca-Vaxzevria was not effective at preventing symptomatic disease due to Omicron, at ≥15 weeks after the second dose.

- COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report, week 51 (PDF) (Technical report). UK Health Security Agency. 23 December 2021. p. 13. GOV-10820. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

Vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic disease by period after dose 2 and dose 3 ... In all periods, effectiveness was lower for Omicron compared to Delta. Among those who received an AstraZeneca primary course, vaccine effectiveness was around 60% 2 to 4 weeks after either a Pfizer or Moderna booster, then dropped to 35% with a Pfizer booster and 45% with a Moderna booster by 10 weeks after the booster.

- "Update on Omicron". World Health Organization. 28 November 2021. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Ferguson N, Ghani A, Hinsley W, Volz E (22 December 2021). Hospitalisation risk for Omicron cases in England (Technical report). WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling, MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis. Imperial College London. doi:10.25561/93035. Report 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2021.

This showed an apparent difference between those who received AstraZenca (AZ) vaccine versus Pfizer or Moderna (PF/MD) for their primary series ... In broad terms, our estimates suggest that individuals who have received at least 2 vaccine doses remain substantially protected against hospitalisation, even if protection against infection has been largely lost against the Omicron variant

- "Vaxzevria: EMA advises against use in people with history of capillary leak syndrome". European Medicines Agency (Press release). 11 June 2021. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- Cines DB, Bussel JB (June 2021). "SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (23): 2254–2256. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2106315. PMC 8063912. PMID 33861524.

- Lai CC, Ko WC, Chen CJ, Chen PY, Huang YC, Lee PI, Hsueh PR (August 2021). "COVID-19 vaccines and thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome". Expert Review of Vaccines. Taylor and Francis Group. 20 (8): 1027–1035. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1949294. PMID 34176415. S2CID 235661210.

- Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S (June 2021). "Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 Vaccination". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (22): 2092–2101. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. PMC 8095372. PMID 33835769.

- Public Health Agency of Canada, [Agence de la santé publique du Canada] (29 March 2021). "Use of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in younger adults" (Utilisation du vaccin AstraZeneca contre la COVID-19 chez les jeunes adultes). Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- Smadja DM, Yue QY, Chocron R, Sanchez O, Lillo-Le Louet A (July 2021). "Vaccination against COVID-19: insight from arterial and venous thrombosis occurrence using data from VigiBase". The European Respiratory Journal. 58 (1). doi:10.1183/13993003.00956-2021. PMC 8051185. PMID 33863748.

- "COVID-19 vaccine safety update Vaxzevria" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 29 March 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- "COVID-19 vaccine safety update Vaxzevria" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 11 May 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- "Vaxzevria: COVID-19 vaccine safety update" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 14 July 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- "COVID-19 vaccines safety update" (PDF). 3 August 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- Arashkia A, Jalilvand S, Mohajel N, Afchangi A, Azadmanesh K, Salehi-Vaziri M, et al. (October 2020). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 spike (S) protein based vaccine candidates: State of the art and future prospects". Reviews in Medical Virology. 31 (3): e2183. doi:10.1002/rmv.2183. PMC 7646037. PMID 33594794.

- Watanabe Y, Mendonça L, Allen ER, Howe A, Lee M, Allen JD, et al. (January 2021). "Native-like SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein expressed by ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 vaccine". bioRxiv: 2021.01.15.426463. doi:10.1101/2021.01.15.426463. PMC 7836103. PMID 33501433.

- He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (March 1998). "A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95 (5): 2509–14. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.2509H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. PMC 19394. PMID 9482916.

- Thomas P, Smart TG (2005). "HEK293 cell line: a vehicle for the expression of recombinant proteins". J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 51 (3): 187–200. doi:10.1016/j.vascn.2004.08.014. PMID 15862464.

- Kovesdi I, Hedley SJ (August 2010). "Adenoviral producer cells". Viruses. 2 (8): 1681–703. doi:10.3390/v2081681. PMC 3185730. PMID 21994701.

- Dicks MD, et al. (2012). "A novel chimpanzee adenovirus vector with low human seroprevalence: improved systems for vector derivation and comparative immunogenicity". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e40385. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...740385D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040385. PMC 3396660. PMID 22808149.

- "Drug Levels and Effects". COVID-19 vaccines. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2006. PMID 33355732. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- Mishra SK, Tripathi T (2021). "One year update on the COVID-19 pandemic: Where are we now?". Acta Tropica. Elsevier BV. 214: 105778. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105778. ISSN 0001-706X. PMC 7695590. PMID 33253656.

- Wang H, Yang P, Liu K, Guo F, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Jiang C (February 2008). "SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway". Cell Research. 18 (2): 290–301. doi:10.1038/cr.2008.15. PMC 7091891. PMID 18227861.

- "There are no foetal cells in the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine". fullfact.org. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Stevis-Gridneff M, Sanger-Katz M, Weiland N (18 December 2020). "A European Official Reveals a Secret: The U.S. Is Paying More for Coronavirus Vaccines". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Where is the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine made?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Delivering COVID-19 vaccine part 2". Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Increase in vaccine manufacturing capacity and supply for COVID-19 vaccines from AstraZeneca, BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "The Backstory: Vaccitech and its role in co-inventing the Oxford COVID-19 vaccine". Oxford Sciences Innovation. 23 November 2020. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "Oxford team to begin novel coronavirus vaccine research". University of Oxford. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "COVID-19 Oxford Vaccine Trial". COVID-19 Oxford Vaccine Trial. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Oxford team to begin novel coronavirus vaccine research". University of Oxford. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "Covid Vaccine Front-Runner Is Months Ahead of Her Competition". Bloomberg Businessweek. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- "Bill Gates, the Virus and the Quest to Vaccinate the World". The New York Times. 23 November 2020. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- "They Pledged to Donate Rights to Their COVID Vaccine, Then Sold Them to Pharma". Kaiser Health News. 25 August 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "The Oxford vaccine: the trials and tribulations of a world-saving jab". The Guardian. 26 June 2021. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Strasburg J, Woo S (21 October 2020). "Oxford Developed Covid Vaccine, Then Scholars Clashed Over Money". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Oxford Developed Covid Vaccine, Then Scholars Clashed Over Money". MSN. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Keown C. "U.S. gives AstraZeneca $1.2 billion to fund Oxford University coronavirus vaccine — America would get 300 million doses beginning in October". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- Coleman J (10 June 2020). "Final testing stage for potential coronavirus vaccine set to begin in July". The Hill. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "AstraZeneca takes next steps towards broad and equitable access to Oxford University's COVID-19 vaccine". www.astrazeneca.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- "Oxford University's COVID-19 vaccine: next steps towards broad and equitable global access". University of Oxford. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- "Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine research 'was 97% publicly funded'". The Guardian. 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- "AZN, IQV Team Up To Accelerate COVID-19 Vaccine Work, RIGL's ITP Drug Repurposed, IMV On Watch". RTTNews. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Phase 3 Clinical Testing in the US of AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate Begins". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 30 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- "AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine study is put on hold". Stat. 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Wu KJ, Thomas K (8 September 2020). "AstraZeneca Pauses Vaccine Trial for Safety Review". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Loftus P (13 September 2020). "AstraZeneca Covid-19 Vaccine Trials Resume in U.K.". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Grady D, Wu KJ, LaFraniere S (19 September 2020). "AstraZeneca, Under Fire for Vaccine Safety, Releases Trial Blueprints". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "AstraZeneca resumes vaccine trial in talks with US". Japan Today. 3 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "FDA authorises restart of the COVID-19 AZD1222 vaccine US Phase III trial". AstraZeneca (Press release). Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "U.S. health secretary says AstraZeneca trial in United States remains on hold: CNBC". Reuters. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Vaxzevria induced immunity for at least one year following a single dose and strong immune responses following either a late second dose or a third dose" (Press release). AstraZeneca. 28 June 2021. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- "Oxford University breakthrough on global COVID-19 vaccine" (Press release). University of Oxford. 23 November 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Callaway E (November 2020). "Why Oxford's positive COVID vaccine results are puzzling scientists". Nature. 588 (7836): 16–18. Bibcode:2020Natur.588...16C. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03326-w. PMID 33230278. S2CID 227156970.

- "Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine 'dose error' explained". BBC News. 27 November 2020. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Robbins R, Mueller B (25 November 2020). "After Admitting Mistake, AstraZeneca Faces Difficult Questions About Its Vaccine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Boseley S (26 November 2020). "Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine to undergo new global trial". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Voysey M, Clemens SA, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. (January 2021). "Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK". Lancet. 397 (10269): 99–111. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7723445. PMID 33306989.

- Smout A (28 June 2021). "Oxford COVID vaccine produces strong immune response from booster shot". Reuters. London. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- "AZD1222 US Phase III trial met primary efficacy endpoint in preventing COVID-19 at interim analysis". www.astrazeneca.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Robbins R, Kaplan S (22 March 2021). "AstraZeneca Vaccine Trial Results Are Questioned by U.S. Health Officials". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "NIAID Statement on AstraZeneca Vaccine". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "AstraZeneca may have used 'outdated information' on vaccine". Stat. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "Mishaps, miscommunications overshadow AstraZeneca's Covid vaccine". Stat. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Herper M (25 March 2021). "New AstraZeneca analysis confirms efficacy of its Covid-19 vaccine". Stat. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine shows 74% efficacy in large US trial". The Straits Times. 29 September 2021. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- "Phase 3 Safety and Efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) Covid-19 Vaccine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 29 September 2021.

- Vasileiou E, Simpson CR, Shi T, Kerr S, Agrawal U, Akbari A, et al. (April 2021). "Interim findings from first-dose mass COVID-19 vaccination roll-out and COVID-19 hospital admissions in Scotland: a national prospective cohort study". Lancet. 397 (10285): 1646–1657. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00677-2. PMC 8064669. PMID 33901420.

- "University of Oxford to study nasal administration of COVID-19 vaccine". University of Oxford. 25 March 2021. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "A Study of Intranasal ChAdOx1 nCOV-19". clinicaltrials.gov. United States National Library of Medicine. 25 March 2021. NCT04816019. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "Government asks regulator to approve supply of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine". Government of the United Kingdom. 27 October 2020. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine authorised by UK medicines regulator". Government of the United Kingdom. 30 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- "EMA receives application for conditional marketing authorisation of COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 12 January 2021. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Vaxzevria Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Everything You Need to Know About the Oxford-AstraZeneca Vaccine". 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.