Pacific Islander

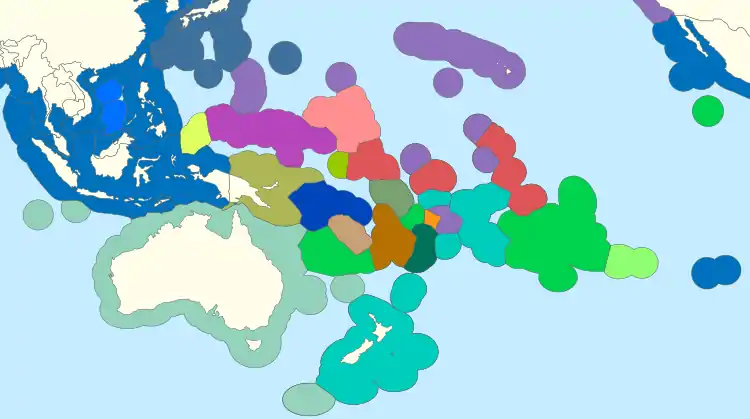

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, Pacificans or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands.[1] As an ethnic/racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas[1]—of any of the three major subregions of Oceania (Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia).

Melanesians include the Fijians (Fiji), Kanaks (New Caledonia), Ni-Vanuatu (Vanuatu), Papua New Guineans (Papua New Guinea), Solomon Islanders (Solomon Islands), and West Papuans (Indonesia's West Papua).

Micronesians include the Carolinians (Caroline Islands), Chamorros (Guam and Northern Mariana Islands), Chuukese (Chuuk), I-Kiribati (Kiribati), Kosraeans (Kosrae), Marshallese (Marshall Islands), Palauans (Palau), Pohnpeians (Pohnpei), and Yapese (Yap).

Polynesians include the New Zealand Māori (New Zealand), Native Hawaiians (Hawaii), Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Samoans (Samoa and American Samoa), Tahitians (Tahiti), Tokelauans (Tokelau), Niueans (Niue), Cook Islands Māori (Cook Islands) and Tongans (Tonga).[1] The term Pasifika was first used in New Zealand to describe the non-indigenous ethnic group(s) that had immigrated to the country from the previously listed Pacific countries (excluding New Zealand). When used in New Zealand, this term excludes the indigenous Māori people.[2]

Auckland, New Zealand has the world's largest concentration of urban Pacific Islanders living outside of their own countries, and is sometimes referred to as the "Polynesian capital of the world."[3] This came as result of a steady stream of immigration from Polynesian countries such as Samoa, Tonga, the Cook Islands, Niue, and French Polynesia in the 20th and 21st centuries.[3]

The umbrella terms Pacific Islands and Pacific Islanders may also take on several other meanings.[4] At times, the term Pacific Islands only refers to islands within the cultural regions of Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia,[5][6] and to tropical islands with oceanic geology in general, such as Clipperton Island.[7] In some common uses, the term refers to the islands of the Pacific Ocean once colonized by the Portuguese, Spaniards, Dutch, British, French, Germans, Americans, and Japanese.[8] In other uses, it may refer to areas with Austronesian linguistic heritage like Taiwan, Indonesia, Micronesia, Polynesia and the Myanmar islands, which found their genesis in the Neolithic cultures of the island of Taiwan.[9] In an often geopolitical context, the term has been extended even further to include the large South Pacific landmass of Australia.[10]

Extent

In the North Pacific, non-tropical islands in and around Alaska, Japan and Russia were inhabited by people related to Indigenous American and Far East Asian groups,[11] with some Japanese ethnic groups also being theorized to be related to Indigenous Pacific groups.[12] In the South Pacific, the easternmost oceanic island with any human inhabitation was Easter Island, settled by the Polynesian Rapa Nui people.[13] Oceanic islands beyond that which neighbor Central America and South America (Galápagos, Revillagigedo, Juan Fernández Islands etc.) are among the last inhabitable places on earth to have been discovered by humans.[14][15] All of these islands (excluding Clipperton) were annexed by Latin American nations a few hundred years after their discoveries, and initially were sometimes used as prisons for convicts.[16] Today only a small number of them are inhabited, mainly by Spanish-speaking mainlanders of mestizo or White Latin American origin.[16] These individuals are not considered Pacific Islanders under the standard ethnically-based definition.[10][11] In a broad sense, they could still possibly be seen as encompassing a small Spanish-speaking segment of Oceania, along with the Easter Island inhabitants, who were eventually colonized by Chileans.[16][17] The 1996 book Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas notes that Spanish was once commonly spoken in the Pacific on the colonial-era Philippines, further stating, "at the present time, the Spanish language is not widely used in the South Pacific, being unknown outside of a handful of places. Spanish is spoken by a resident population only on the Ecuadorian Galápagos Islands, the Chilean possessions of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Juan Fernández Islands and a few other tiny islands. Most Pacific insular possessions of Latin American nations are either unpopulated or used as military outposts, staffed by natives of the mainland."[18]

Lord Howe Island, located between Australia and New Zealand, is one of the only other habitable oceanic islands to have had no contact with humans prior to European discovery.[19] The island is currently administered by Australia, and Its residents are primarily European Australians who originated from the mainland, with a small number also being Asian Australians.[20] Like with the Spanish-speaking islanders in the southeastern Pacific, they would not normally be considered Pacific Islanders under a ethnically-based definition. Remote and uninhabitable islands in the central Pacific such as Baker Island were also generally isolated from humans prior to European discovery.[21] However, Pacific Islanders are believed to have possibly visited some of these locations, including Wake Island.[21][22] In the case of Howland Island, there may have even been a brief attempt at settlement.[22]

The Official Journal of the Asia Oceania Geosciences Society (AOGS) considers the term Pacific Islands to encompass American Samoa, Cook Islands, Easter Island, the Galápagos Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Hawaii, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn Islands, Salas y Gómez Island, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, the United States Minor Outlying Islands, Vanuatu and Wallis and Futuna.[23] The 1982 edition of the South Pacific Handbook, by David Stanley, groups Australia, New Zealand, Norfolk Island and the islands of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia under the more restrictive label of the "South Pacific Islands", even though Hawaii and most islands in Micronesia technically lie in the North Pacific. He additionally includes the Galápagos Islands in his definition of the South Pacific, but does not include any other islands located within the southeastern Pacific area, aside from Easter Island which is considered part of Polynesia.[24]

.png.webp)

Ian Todd's 1974 book Island Realm: A Pacific Panorama considers Oceania and the term "Pacific Islands" to also encompass the non-tropical Aleutian Islands,[25] as well as Clipperton Island, the Coral Sea Islands, the Desventuradas Islands, Guadalupe Island, the Juan Fernández Islands, the Revillagigedo Islands, Salas y Gómez Island and the Torres Strait Islands. He notes that the terms are sometimes taken to include Australia, New Zealand and the non-oceanic Papua New Guinea, however he does not consider them to encompass the Japanese archipelago, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, Russia's Kuril Islands and Sakhalin Island or countries associated with Maritime Southeast Asia. The Philippines according to him are at a "cross-roads of the Pacific — a racial and geographic link connecting Oceania, Southeast Asia and Indonesia."[17] Debate exists over whether or not the Philippines should be categorized with Pacific Islands of shared Austronesian origin or with the mainland nations of Asia.[26][27][28][29] The islands of the Philippines do not have oceanic geology, and instead sit on the continental shelf of Asia. As such, they are sometimes deemed as a geological extension of Asia.[25] In his 2012 book Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education, American author James A. Banks claimed that, "although islands such as the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan, Japan and the Aleutian Islands are located in the Pacific Ocean, islanders from these locales are not typically considered Pacific Islanders. They are usually considered Asian, with Aleuts considered Alaskan natives."[30]Thus, because proximity does not determine ethnicity, only through defined connections such as Maori(Polynesian) and Rapa Nui natives(Polynesian) it has to be evident that "islands" although nearby to Oceana, the inhabitants though distantly connected by similarities in language and practices similar to Melanesians, Micronesians and Polynesians are to be considered Southeast Asian, such as the Phillipines.

The Pacific Islands Forum is the major governing organization for the Pacific Islands, and has been labelled as the "EU of the Pacific region".[31] Up until 2021, its member nations and associate members were American Samoa, Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Wallis and Futuna.[32] Additionally, there have been pushes for Easter Island and Hawaii to join the Pacific Islands Forum, as they are primarily inhabited by Polynesian peoples.[33] Japan and Malay Archipelago countries such as East Timor, Indonesia and the Philippines are dialogue partners of the Pacific Islands Forum, with East Timor having observer status, but none are full members.[32] The nations of the Malay Archipelago have their own regional governing organization called ASEAN, which includes mainland Southeast Asian nations such as Vietnam and Thailand. In July 2019, at the inaugural Indonesian Exposition held in Auckland, Indonesia launched its ‘Pacific Elevation’ program, which would encompass a new era of elevated engagement with the region, with the country also using the event to lay claim that Indonesia is culturally and ethnically linked to the Pacific islands. The event was attended by dignitaries from Australia, New Zealand and some Pacific island countries.[34]

Australia and New Zealand have been described as both continental landmasses and as Pacific Islands. New Zealand's native population, the Māori, are Polynesians, and thus considered Pacific Islanders. Australia's Indigenous population are loosely related to Melanesians and the United States Census categorize them under the Pacific Islander American umbrella.[35][36][37] In Island Realm: A Pacific Panorama (1974), Ian Todd states that, "New Zealand is uniquely gifted in its role as a Polynesian associate. A large section of its own indigenous population consists of Māori — a Polynesian race. Beyond her own sphere of association, New Zealand's trading influence is prominent in Tonga, Fiji and other areas of the Pacific with Commonwealth affiliations." Regarding Australia, he further wrote, "Australia plays a leading economic role in the south-west Pacific area — commonly known as Melanesia. Fiji, the New Hebrides, the Solomons, even French-controlled New Caledonia have a major trade connection with Australia. The thriving little republic of Nauru was administered by Australia before its recent independence. Further afield, in western Polynesia, Australia provides economic and technical aid in Tonga and Western Samoa. Much of Fiji's tourist trade comes from 'down under'. Among the oceanic islands which are part of the Commonwealth of Australia are Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island, the Torres Strait Islands, the Willis Group and Coringa Islands."[17]

Pacific Islander regions

The Pacific islands consist of three main traditional regions.

Melanesia

Melanesia is the great arc of islands located north and east of Australia and south of the Equator. The name derives the Greek words melas ('black') and nēsos ('island') for the predominantly dark-skinned peoples of New Guinea island, the Bismarck Archipelago, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu (formerly New Hebrides), New Caledonia, and Fiji.[38]

In addition those places listed above, Melanesia includes the Louisiade Archipelago, the Admiralty Islands, Bougainville Island, Papua New Guinea, Western New Guinea (part of Indonesia), Maluku Island, Aru Islands, Kei Islands, the Santa Cruz Islands (part of the Solomon Islands), Loyalty Islands (part of New Caledonia) and various smaller islands. East Timor, while considered to be geographically Southeast Asian, is still generally accepted as being ethnoculturally part of Melanesia. The Torres Strait Islands are politically part of nearby Queensland, Australia, although the inhabitants are considered to be Melanesians rather than Indigenous Australians.[39] This is not the case with other Australian islands that were inhabited by Indigenous peoples prior to European discovery, such as Fraser Island, Great Palm Island and the Tiwi Islands. The Torres Strait Islands could be seen as a Melanesian territory in Australasia, similar to how East Timor is a Melanesian territory in Asia. Norfolk Island was uninhabited when discovered by Europeans, and later became politically integrated into Australia (and by extension, Australasia).[39] The remote island is still sometimes considered to be in Melanesia, as it is close to the region, and has archeological evidence of prehistoric inhabitation.

New Caledonia (and Vanuatu to a lesser extent) were under French colonial influence from the 19th century onward.[40] Most islands however have historically had close ties to Australia and the United Kingdom, with the United States having had little impact on the region.[40][41]

Micronesia

Micronesia includes Kiribati, Nauru, the Marianas (Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands), the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Palau, and the Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae, all in the Caroline Islands).

The islands were under the influence of colonial powers such as Germany, Spain and Japan from the 16th century up until the end of World War II. Several of the island groups have since developed financially crucial political alignments with the United States.[40] Nauru's main political partner since World War I has been Australia, excluding a brief period of Japanese occupation in World War II.[40][42]

Polynesia

The Polynesian islands are scattered across a triangle covering the east-central region of the Pacific Ocean. The triangle is bound by the Hawaiian Islands in the north, New Zealand in the west, and Easter Island in the east. The rest of Polynesia includes the Samoan islands (American Samoa and Samoa [formerly Western Samoa]); Cook Islands; French Polynesia (the Society Islands [Tahiti], Marquesas Islands, Austral Islands, and Tuamotu); Niue Island; Tokelau and Tuvalu; Tonga; Wallis and Futuna; Rotuma Island; Pitcairn Island; Nukuoro; and Kapingamarangi.[38]

The majority of island groups are most closely aligned to New Zealand/Australia, with others being politically aligned to France or the United States.[40] Hawaii is geographically isolated from Polynesia, and is situated in the North Pacific, unlike the rest of Polynesia, which is in the South Pacific. They are still a part of the subregion for ethnocultural reasons. Easter Island is located in a remote part of the Pacific which is thousands of kilometers removed from both Polynesia and the South American continent. It was annexed by Chile in 1888, and Spanish is now commonly spoken in a bilingual manner, with some having race-mixed with Mestizo Chilean settlers. However, the inhabitants consider their island and its culture to be Polynesian, and do not view themselves as South Americans.[43][10]

Ethnic groups

The population of the Pacific Islands is concentrated in Papua New Guinea, New Zealand (which has a majority of people of European descent), Hawaii, Fiji, and Solomon Islands. Most Pacific Islands are densely populated, and habitation tends to be concentrated along the coasts.[38]

Melanesians constitute over three quarters of the total indigenous population of the Pacific Islands; Polynesians account for more than one-sixth; and Micronesians make up about one-twentieth.[38]

Ethnolinguistics

Several hundred distinct languages are spoken in the Pacific Islands. In ethnolinguistic terms, the Pacific islanders of Oceania are divided into two different ethnic classifications:[38]

- Austronesian-speaking peoples — Austronesian peoples who speak the Oceanian languages, numbering about 2.3 million in population, who occupy Polynesia, Micronesia, and most of the smaller islands of Melanesia.

- Papuan-speaking peoples — Papuan peoples who speak the Papuan languages (the mutually unrelated, non-Austronesian language families), numbering about 7 million in population, and mostly reside on the island of New Guinea and a few of the smaller islands of Melanesia located off the northeast coast of New Guinea.[44]

List of Pacific peoples

- Austronesian-speaking peoples

- Polynesians

- Melanesians

- Micronesians

- Marshallese

- Palauans

- Refaluwasch

- Tanapag

- Chamorros

- Chuukese

- Yapese

- Kiribati

- Kosraeans

- Pohnpeians

- Nauruans

- Mokilese

- Pingelapese

- Ulithian

- Satawalese

- woleaian

- namonuito

- Pááfang

- Mortlockese

- Ngatikese

- Puluwatese

- Sonsorolese

- Tobian

- Nguluwan

- Mapia

- Banaban

- Polynesian Outliers in Micronesia region

- Kapingamarangi

- Nukuoro

- Papuan-speaking peoples

- Papua New Guinea region

- Papua region

- Indonesian New Guinea/West Papua region (see List of ethnic groups of West Papua)

Terminology by country

Australia

In Australia, the term South Sea Islander was used to describe Australian descendants of people from the over-80 islands in the western Pacific who had been brought to Australia to work on the sugar fields of Queensland—these people were called Kanakas in the 19th century.[45]

The Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 was enacted to restrict entry of Pacific Islanders to Australia and to authorise their deportation. In this legislation, Pacific Islanders were defined as:

"Pacific Island Labourer" includes all natives not of European extraction of any island except the islands of New Zealand situated in the Pacific Ocean beyond the Commonwealth [of Australia] as constituted at the commencement of this Act.[46]

Despite this, Pacific Islanders were generally held in a much higher regard than Indigenous Australians were during the early 20th century.[40]

In 2008, a "Pacific Seasonal Worker Pilot Scheme" was announced as a three-year pilot experiment.[47] It provides visas for workers from Kiribati, Tonga, Vanuatu, and Papua New Guinea to work in Australia.[48] Aside from Papua New Guinea, the scheme includes one country each from Melanesia (Vanuatu), Polynesia (Tonga), and Micronesia (Kiribati)—countries that already send workers to New Zealand under its seasonal labour scheme.[49][50]

New Zealand

Local usage in New Zealand uses Pacific Islander (also called Pasifika, or formerly Pacific Polynesians,[51]) to distinguish those who have emigrated from one of these areas in modern times from the New Zealand Māori, who are also Polynesian but are indigenous to New Zealand.[51]

In the 2013 New Zealand census, 7.4% of the New Zealand population identified with one or more Pacific ethnic groups, although 62.3% of these were born in New Zealand.[52] Those with a Samoan background make up the largest proportion, followed by Cook Islands Māori, Tongan, and Niuean.[52] Some smaller island populations such as Niue and Tokelau have the majority of their nationals living in New Zealand.[53]

To celebrate the diverse Pacific island cultures, the Auckland Region hosts several Pacific island festivals. Two of the major ones are Polyfest, which showcases performances of the secondary school cultural groups in the region,[54] and Pasifika, a festival that celebrates Pacific island heritage through traditional food, music, dance, and entertainment.[55]

United States

By the 1980s, the United States Census Bureau grouped persons of Asian ancestry and created the category "Asian-Pacific Islander," which continued in the 1990s census. In 2000, "Asian" and "Pacific Islander" became two separate racial categories.[56]

According to the Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program (PEP), a "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander" is,

A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific islands. It includes people who indicate their race as 'Native Hawaiian', 'Guamanian or Chamorro', 'Samoan', and 'Other Pacific Islander' or provide other detailed Pacific Islander responses.[57]

According to the Office of Management and Budget, "Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander" refers to a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.[56]

Eight out of 10 Pacific Islanders in the United States are native to the United States. Polynesians make up the largest group, including Native Hawaiians, Samoans, Tahitians, and Tongans. Micronesians make up the second largest, including primarily Chamoru from Guam; as well as other Chamoru, Carolinian from the Northern Mariana Islands, Marshallese, Palauans, and various others. Among Melanesians, Fijian Americans are the largest in this group.[58]

There are at least 39 different Pacific Island languages spoken as a second language in the American home.[58]

See also

References

- "Defining Diaspora: Asian, Pacific Islander, and Desi Identities | Cross-Cultural Center | CSUSM". www.csusm.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-09.

- "Pacific and Pasifika Terminology". tepasa.tki.org. Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga│Ministry of Education. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- "Pacific Islanders". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- Collins Atlas of the World (revised ed.), London: HarperCollins, 1995 [1983], ISBN 0-00-448227-1

- D'Arcy, Paul (March 2006). The People of the Sea: Environment, Identity, and History in Oceania. University Of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3297-1. Archived from the original on 2014-10-30. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Rapaport, Moshe (April 2013). The Pacific Islands: Environment and Society, Revised Edition. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6584-9. JSTOR j.ctt6wqh08.

This is the only contemporary text on the Pacific Islands that covers both environment and sociocultural issues and will thus be indispensable for any serious student of the region. Unlike other reviews, it treats the entirety of Oceania (with the exception of Australia) and is well illustrated with numerous photos and maps, including a regional atlas.

– via JSTOR (subscription required) - Mueller-Dombois, Dieter; Fosberg, Frederic R. (1998). Vegetation of the Tropical Pacific Islands. Springer. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Wright, John K. (July 1942). "Pacific Islands". Geographical Review. 32 (3): 481–486. doi:10.2307/210391. JSTOR 210391. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Compare: Blundell, David (January 2011). "Taiwan Austronesian Language Heritage Connecting Pacific Island Peoples: Diplomacy and Values" (PDF). International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies. 7 (1): 75–91. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

Taiwan associations are based on almost forgotten old connections with far-reaching Pacific linguistic origins. The present term Austronesia is based on linguistics and archaeology supporting the origins and existence of the Austronesian Language family spread across the Pacific on modern Taiwan, Indonesia, East Timor, Malaysia,, Singapore, Brunei, Micronesia, Polynesia, the non-Papuan languages of Melanesia, the Cham areas of Vietnam, Cambodia, Hainan, Myanmar islands, and some Indian Ocean islands including Madagascar. Taiwan is in the initiating region.

- Crocombe, R. G. (2007). Asia in the Pacific Islands: Replacing the West. University of the South Pacific. Institute of Pacific Studies. p. 13. ISBN 9789820203884. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Search tips - Pacific Islander Research Starter - Academic Guides at Walden University". Academicguides.waldenu.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- Hudson, Mark J. (2017). "The Ryukyu Islands and the Northern Frontier of Prehistoric Austronesian Settlement" (PDF). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. Vol. 45. ANU Press. pp. 189–200. ISBN 9781760460945. JSTOR j.ctt1pwtd26.17.

- Flett, Iona; Haberle, Simon (2008). "East of Easter: Traces of human impact in the far-eastern Pacific" (PDF). In Clark, Geoffrey; Leach, Foss; O'Connor, Sue (eds.). Islands of Inquiry. ANU Press. pp. 281–300. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.8988. hdl:1885/38139. ISBN 978-1-921313-89-9. JSTOR j.ctt24h8gp.20.

- Macnaughtan, Don (February 1, 2014). "Mystery Islands of Remote East Polynesia: Bibliography of Prehistoric Settlement on the Pitcairn Islands Group". Wordpress: Don Macnaughtan's Bibliographies – via www.academia.edu.

- Sues, Hans-Diete; MacPhee, Ross D.E (1999). Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. Springer US. p. 29. ISBN 9780306460920. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

The human colonization of remote Oceania occurred in the late Holocene. Prehistoric human explorers missed only the Galápagos and a very few out-of-the-way places as they surged east out of the Solomons, island-hopping thousands of kilometers through the Polynesian heartland to reach Hawaii to the far north, Easter Island over 7500km to the east and, New Zealand to the south

- Sebeok, Thomas Albert (1971). Current Trends in Linguistics: Linguistics in Oceania. the University of Michigan. p. 950. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

Most of this account of the influence of the Hispanic languages in Oceania has dealt with the Western Pacific, but the Eastern Pacific has not been without some share of the presence of the Portuguese and Spanish. The Eastern Pacific does not have the multitude of islands so characteristic of the Western regions of this great ocean, but there are some: Easter Island, 2000 miles off the Chilean coast, where a Polynesian tongue, Rapanui, is still spoken; the Juan Fernandez group, 400 miles west of Valparaiso; the Galapagos archipelago, 650 miles west of Ecuador; Malpelo and Cocos, 300 miles off the Colombian and Costa Rican coasts respectively; and others. Not many of these islands have extensive populations — some have been used effectively as prisons — but the official language on each is Spanish.

- Todd, Ian (1974). Island Realm: A Pacific Panorama. Angus & Robertson. p. 190. ISBN 9780207127618. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

[we] can further define the word culture to mean language. Thus we have the French language part of Oceania, the Spanish part and the Japanese part. The Japanese culture groups of Oceania are the Bonin Islands, the Marcus Islands and the Volcano Islands. These three clusters, lying south and south-east of Japan, are inhabited either by Japanese or by people who have now completely fused with the Japanese race. Therefore they will not be taken into account in the proposed comparison of the policies of non - Oceanic cultures towards Oceanic peoples. On the eastern side of the Pacific are a number of Spanish language culture groups of islands. Two of them, the Galapagos and Easter Island, have been dealt with as separate chapters in this volume. Only one of the dozen or so Spanish culture island groups of Oceania has an Oceanic population — the Polynesians of Easter Island. The rest are either uninhabited or have a Spanish - Latin - American population consisting of people who migrated from the mainland. Therefore, the comparisons which follow refer almost exclusively to the English and French language cultures.

- Wurm, Stephen A.; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T., eds. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Vol. 1–2. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110819724. ISBN 9783110134179.

- Anderson, Atholl (2003). "Investigating early settlement on Lord Howe Island" (PDF). Australian Archaeology. 57 (57): 98–102. doi:10.1080/03122417.2003.11681767. S2CID 142367492. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Bywater, Thomas (7 June 2022). "Hollywood on Howe: Australia's Most Exclusive Ecotourism Spot". Nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the U.S. Pacific Remote Island Areas (PDF) (Report). SPREP. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Hague, James D. Web copy "Our Equatorial Islands with an Account of Some Personal Experiences". Archived 6 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Century Magazine, Vol. LXIV, No. 5, September 1902. Retrieved: 3 January 2008.

- Nunn, Patrick D.; Kumar, Lalit; Eliot, Ian; McLean, Roger F. (2016-03-02). "Classifying Pacific islands". Geoscience Letters. Geoscienceletters.springeropen.com. 3: 7. Bibcode:2016GSL.....3....7N. doi:10.1186/s40562-016-0041-8. S2CID 53970527.

- Stanley, David (1982). South Pacific Handbook. Moon Publications. p. 502. ISBN 9780960332236. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Henderson, John William (1971). Area Handbook for Oceania. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 5. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Oreiro, Brandon (2014). Overcoming Panethnicity: Filipino-American Identity in a Globalized Culture (Essay). University of Washington, Tacoma.

- Palatino, Mong. "Are Filipinos Asian?". thediplomat.com.

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation (1998). Encyclopedia of Earth and Physical Sciences: Nuclear physics-Plate tectonics. Pennsylvania State University. p. 876. ISBN 9780761405511. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Wikstrom, Eleanor V. (13 December 2021). "Scars of Empire: Harvard's Role in U.S. Colonialism in the Philippines". The Harvard Crimson.

- Banks, James A. (2012). Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781506320335. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- Australia West Papua Association (22 October 2005). "West Papua Should Have Observer Status". Scoop News (Press release). Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- "The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF)". Coopération Régionale et Relations Extérieures de la Nouvelle-Calédonie. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- Dorney, Sean (27 August 2012). "Pacific Forum Looks to Widen Entry". ABC News. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius (13 January 2020). "Indonesia's "Pacific Elevation": Elevating What and Who?". Griffith Asia Insights. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- University of Virginia. Geospatial and Statistical Data Center. "1990 PUMS Ancestry Codes." 2003. August 30, 2007."1990 Census of Population and Housing Public Use Microdata Sample". Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- "Clark Library - U-M Library". www.lib.umich.edu.

- Ernst, Manfred; Anisi, Anna (2016). "The Historical Development of Christianity in Oceania". In Sanneh, Lamin; McClymond, Michael J. (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to World Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 588–604 – via Academia.edu.

- West, F. James, and Sophie Foster. 2020 November 17. "Pacific Islands." Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Aldrich, Robert (1993). France and the South Pacific Since 1940. University of Hawaii Press. p. 347. ISBN 9780824815585. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

Britain's high commissioner in New Zealand continues to administer Pitcairn, and the other former British colonies remain members of the Commonwealth of Nations, recognizing the British Queen as their titular head of state and vesting certain residual powers in the British government or the Queen's representative in the islands. Australia did not cede control of the Torres Strait Islands, inhabited by a Melanesian population, or Lord Howe and Norfolk Island, whose residents are of European ancestry. New Zealand retains indirect rule over Niue and Tokelau and has kept close relations with another former possession, the Cook Islands, through a compact of free association. Chile rules Easter Island (Rapa Nui) and Ecuador rules the Galapagos Islands. The Aboriginals of Australia, the Maoris of New Zealand and the native Polynesians of Hawaii, despite movements demanding more cultural recognition, greater economic and political considerations or even outright sovereignty, have remained minorities in countries where massive waves of migration have completely changed society. In short, Oceania has remained one of the least completely decolonized regions on the globe.

- Halter, Nicholas (2021). Australian Travellers in the South Seas. ANU Press. ISBN 9781760464158. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- Fraenkel, Jon; Woolrych, Katharine (2020-07-09). "NZ and Australia: Big Brothers or Distant Cousins?". The Interpreter. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- Nancy Viviani (1970). Nauru: Phosphate and Political Progress (PDF). Canberra: Australian National University Press. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- SBS Australia (November 2004). "Saving the Rapanui". YouTube. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Friedlaender, Jonathan S.; Friedlaender, Françoise R.; Reed, Floyd A.; Kidd, Kenneth K.; Kidd, Judith R.; Chambers, Geoffrey K.; Lea, Rodney A.; Loo, Jun-Hun; Koki, George; Hodgson, Jason A.; Merriwether, D. Andrew; Weber, James L. (2008). "The Genetic Structure of Pacific Islanders". PLOS Genetics. 4 (1). e19. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0040019. PMC 2211537. PMID 18208337.

- "South Sea Islander Project". ABC Radio Regional Production Fund. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2004. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

Recognition for Australian South Sea Islanders (ASSI) has been a long time coming. It was not until 1994 that the federal government recognized them as a distinct ethnic group with their own history and culture and not until September 2000 that the Queensland government made a formal statement of recognition.

- "Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 (Cth)" (PDF). Documenting a Democracy. National Archives of Australia. 1901. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- Australian Institute of Criminology: Australia's Pacific Seasonal Worker Pilot Scheme: Managing vulnerabilities to exploitation Archived 2020-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pacific guestworker scheme to start this year". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2008-08-17.

- "Seasonal Worker Pilot Scheme is more proof of Australia's new Pacific focus" (Press release). The Hon Duncan Kerr SC MP; Parliamentary Secretary for Pacific Island Affairs. 2008-08-20. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- Australian classification standards code Pacific islanders, Oceanians, South Sea islanders, and Australasians all with code 1000, i.e., identically. This coding can be broken down into the finer classification of 1,100 Australian Peoples; 1,200 New Zealand peoples; 1,300 Melanesian and Papuan; 1,400 Micronesian; 1,500 Polynesian. There is no specific coding therefore for "Pacific islander"."Australian Standard Classification of Cultural and Ethnic Groups (ASCCEG) - 2nd edition" (pdf - 136 pages). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2005-07-07. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- Crocombe, R. G. (1992). Pacific Neighbours: New Zealand's Relations with Other Pacific Islands : Aotearoa Me Nga Moutere O Te Moana Nui a Kiwa. University of the South Pacific. p. xxi. ISBN 978-982-02-0078-4.

- "Pacific peoples ethnic group", 2013 Census. Statistics New Zealand. Accessed on 18 August 2017.

- Smelt, and Lin, 1998

- "Polyfest NCEA credits / Pasifika Education Plan / Home - Pasifika". Te Kete Ipurangi (TKI). Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "Thousands turn out for Pasifika Festival". Radio New Zealand. 25 March 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders — a FAQ". NBC News. May 2019. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- "Information on Race". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-20. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Lal, B., and K. Fortune, eds. 2000. "The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia." Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. 2015. American History Unbound: Asians and Pacific Islanders. University of California Press..

- Smelt, R., and Y. Lin. 1998. Cultures of the world: New Zealand. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark.

- Thomas, Nicholas. 2010. Islanders: The Pacific in the Age of Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12438-5.

- "Pacific Islanders in the NZEF." New Zealand History Online. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 2019 March 26.

External links

- Asian Pacific Americans in the U.S. Army

- Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Association

- Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples — exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History

- Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved March 21, 2013.