Tally stick

A tally stick (or simply tally[1]) was an ancient memory aid device used to record and document numbers, quantities and messages. Tally sticks first appear as animal bones carved with notches during the Upper Palaeolithic; a notable example is the Ishango Bone. Historical reference is made by Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) about the best wood to use for tallies, and by Marco Polo (1254–1324) who mentions the use of the tally in China. Tallies have been used for numerous purposes such as messaging and scheduling, and especially in financial and legal transactions, to the point of being currency.

Kinds of tallies

Principally, there are two different kinds of tally sticks: the single tally and the split tally. A common form of the same kind of primitive counting device is seen in various kinds of prayer beads.

Possible palaeolithic tally sticks

A number of anthropological artefacts have been conjectured to be tally sticks:

- The Lebombo bone, dated between 44,200 and 43,000 years old, is a baboon's fibula with 29 distinct notches, discovered within the Border Cave in the Lebombo Mountains of Eswatini.

- The so-called Wolf bone (cs) is a prehistoric artefact discovered in 1937 in Czechoslovakia during excavations at Dolní Věstonice, Moravia, led by Karl Absolon. Dated to the Aurignacian, approximately 30,000 years ago, the bone is marked with 55 marks which some believe to be tally marks. The head of an ivory Venus figurine was excavated close to the bone.[2][3]

- The Ishango bone is a bone tool, dated to the Upper Palaeolithic era, around 18,000 to 20,000 BC. It is a dark brown length of bone. It has a series of possible tally marks carved in three columns running the length of the tool. It was found in 1950 in Ishango (east Belgian Congo).[4]

Single tally

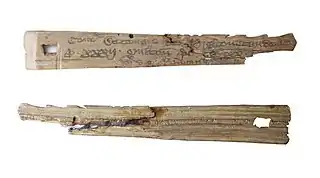

The single tally stick was an elongated piece of bone, ivory, wood, or stone which is marked with a system of notches (see: Tally marks). The single tally stick serves predominantly mnemonic purposes. Related to the single tally concept are messenger sticks (used by, e.g., Inuit tribes), the knotted cords, khipus or quipus, as used by the Inca. Herodotus (c. 485–425 BC) reported the use of a knotted cord by Darius I of Persia (c. 521–486 BC).

Split tally

The split tally was a technique which became common in medieval Europe, which was constantly short of money (coins) and predominantly illiterate, in order to record bilateral exchange and debts. A stick (squared hazelwood sticks were most common) was marked with a system of notches and then split lengthwise. This way the two halves both record the same notches and each party to the transaction received one half of the marked stick as proof. Later this technique was refined in various ways and became virtually tamper proof. One of the refinements was to make the two halves of the stick of different lengths. The longer part was called stock and was given to the party which had advanced money (or other items) to the receiver. The shorter portion of the stick was called foil and was given to the party which had received the funds or goods. Using this technique each of the parties had an identifiable record of the transaction. The natural irregularities in the surfaces of the tallies where they were split would mean that only the original two halves would fit back together perfectly, and so would verify that they were matching halves of the same transaction. If one party tried to unilaterally change the value of his half of the tally stick by adding more notches, the absence of those notches would be apparent on the other party's tally stick. The split tally was accepted as legal proof in medieval courts and the Napoleonic Code (1804) still makes reference to the tally stick in Article 1333.[5] Along the Danube and in Switzerland the tally was still used in the 20th century in rural economies.

The most prominent and best recorded use of the split tally stick or "nick-stick"[6][7] being used as a form of currency[8] was when Henry I introduced the tally stick system in medieval England in around 1100. The tally sticks recorded a payment of taxes, but soon began to circulate in a secondary discount market, being accepted as payment for goods and services at a discount since they could be later presented to the treasury as proof of taxes paid. Then tally sticks began to be issued in advance, in order to finance war and other royal spending, and circulated as "wooden money".[9][10]

The system of tally marks of the Exchequer is described in The Dialogue Concerning the Exchequer as follows:

The manner of cutting is as follows. At the top of the tally a cut is made, the thickness of the palm of the hand, to represent a thousand pounds; then a hundred pounds by a cut the breadth of a thumb; twenty pounds, the breadth of the little finger; a single pound, the width of a swollen barleycorn; a shilling rather narrower; then a penny is marked by a single cut without removing any wood.

The cuts were made the full width of the stick so that, after splitting, the portion kept by the issuer (the stock) exactly matched the piece (the foil) given as a receipt. Each stick had to have the details of the transaction written on it, in ink, to make it a valid record.[11]

Royal tallies (debt of the Crown) also played a role in the formation of the Bank of England at the end of the 17th century. In 1697, the bank issued £1 million worth of stock in exchange for £800,000 worth of tallies at par and £200,000 in bank notes. This new stock was said to be "engrafted". The government promised not only to pay the Bank interest on the tallies subscribed but to redeem them over a period of years. The "engrafted" stock was then cancelled simultaneously with the redemption.[12]

The split tally of the Exchequer remained in continuous use in England until 1826, when the conditions required for activation of the Receipt of the Exchequer Act 1783 (23 Geo. 3. c. 82), the death of the last Exchequer Chamberlain, came about.[13] In 1834, following the passing of 4 Will. 4. c .15, tally sticks representing six centuries' worth of financial records were ordered to be burned in two furnaces in the Houses of Parliament.[14] The resulting fire set the chimney ablaze and then spread until most of the building was destroyed.[8] This event was described by Charles Dickens in an 1855 article on administrative reform.[15]

Tally sticks feature in the design of the entrance gates to The National Archives at Kew.

See also

- Bamboo and wooden slips

- Bamboo tally

- Chirograph: a similar system for creating two or more matching copies of a legal document on parchment

- Fu (tally)

- Measuring rod

- Prehistoric numerals

Notes

- Harper, Douglas. "tally". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Flegg, Graham (2002). Numbers: their history and meaning. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-486-42165-0.

- Beckmann, Petr (1971). A History of π (PI). Boulder, Colorado: The Golem Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-911762-12-9.

- "A very brief history of pure mathematics: The Ishango Bone". University of Western Australia School of Mathematics. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008.

- "Code civil, Article 1333". 1804. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

Les tailles corrélatives à leurs échantillons font foi entre les personnes qui sont dans l'usage de constater ainsi les fournitures qu'elles font ou reçoivent en détail.

- "nick-stick". Oxford English Dictionary (3 ed.). 2003.

- Shenton, Caroline (2012). "Chapter 1: Thursday 16 October 1834, 6am: Mr Hume's Motion for a New House". The Day Parliament Burned Down. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199646708.

- "50 Things That Made the Modern Economy". BBC Radio. BBC. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- How swapping gold for wood left England’s citizens short-changed

- What tally sticks tell us about how money works

- Clanchy, Michael (1979). From Memory to Written Record (3rd ed.). Oxford, England: Blackwell. p. 125. ISBN 9780631168577.

- Carswell, John (1993). The South Sea Bubble (Revised ed.). England: Alan Sutton Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-86299-918-6.

- Robert, Rudoph (1956). "A Short History of Tallies" (PDF). In Littleton, A. C.; Yamey, B. S. (eds.). Studies in the History of Accounting. London: Sweet & Maxwell. pp. 75–85.

- Shenton, Caroline (16 October 2013). "The day Parliament burned down". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Dickens, Charles (1870) [June 27, 1855]. "Administrative Reform". Speeches literary and social by Charles Dickens. Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. pp. 133–134.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

- Maddox, Thomas, ed. (1711). The History and Antiquities of the Exchequer of the Kings of England, in two periods: To wit, from the Norman Conquest, to the End of the Reign of K. John; and from the End of the Reign of K. John, to the End of the Reign of K. Edward II: Taken from Records. London.

- Baxter, T. W. (1989). "Early Accounting, The Tally and the Checkerboard". The Accounting Historians Journal. 16 (2): 43–83. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.16.2.43.

- Jenkinson, (Sir) Hilary (1924). "Medieval Tallies, Public and Private". Archaeologia. 74: 280–351, 8 Plates.

- Carswell, John (1993). The South Sea Bubble (Revised ed.). England: Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-86299-918-6.

Further reading

- Hall, Hubert (1891). The Antiquities and Curiosities of the Exchequer. London: Elliot Stocks.

- Henkelman, Wouter F. M.; L. Folmer, Margaretha (2016). "Your Tally is Full! On Wooden Credit Records in and after the Achaemenid Empire". In Kleber, K.; Pirngruber, R. (eds.). Silver, Money and Credit: Festschrift for Robartus J. van der Spek on occasion of his 65th birthday on 18 September 2014. Publications de l'Institut Historique-Archéologique Néerlandais de Stamboul. Vol. 128. Leiden. pp. 129–226.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jenkinson, (Sir) Hilary (1914). "An original Exchequer Account of 1304 with private Tallies attached". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2nd ser. 26: 36–40.

- Jenkinson, (Sir) Hilary (1911). "Exchequer Tallies". Archaeologia. 62 (2): 367–80. doi:10.1017/s0261340900008213.

- Jenkinson, (Sir) Hilary. "A note supplementary". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2nd ser. 25: 29–39.