Measuring rod

A measuring rod is a tool used to physically measure lengths and survey areas of various sizes. Most measuring rods are round or square sectioned; however, they can also be flat boards. Some have markings at regular intervals. It is likely that the measuring rod was used before the line, chain or steel tapes used in modern measurement.[1]

History

Ancient Sumer

The oldest preserved measuring rod is a copper-alloy bar which was found by the German Assyriologist Eckhard Unger while excavating at Nippur (pictured below). The bar dates from c. 2650 BC. and Unger claimed it was used as a measurement standard. This irregularly formed and irregularly marked graduated rule supposedly defined the Sumerian cubit as about 518.5 mm (20.4 in), although this does not agree with other evidence from the statues of Gudea from the same region, five centuries later.[2]

Ancient India

Rulers made from ivory were in use by the Indus Valley Civilization in what today is Pakistan, and in some parts of Western India prior to 1500 BCE. Excavations at Lothal dating to 2400 BCE have yielded one such ruler calibrated to about 1⁄16 inch (1.6 mm)[3] Ian Whitelaw (2007) holds that 'The Mohenjo-Daro ruler is divided into units corresponding to 1.32 inches (34 mm) and these are marked out in decimal subdivisions with remarkable accuracy—to within 0.005 inches (0.13 mm). Ancient bricks found throughout the region have dimensions that correspond to these units.'[4] The sum total of ten graduations from Lothal is approximate to the angula in the Arthashastra.[5]

Ancient East Asia

Measuring rods for different purposes and sizes (construction, tailoring and land survey) have been found from China and elsewhere dating to the early 2nd millennium B.C.E.[6]

Ancient Egypt

Cubit-rods of wood or stone were used in Ancient Egypt. Fourteen of these were described and compared by Lepsius in 1865.[7] Flinders Petrie reported on a rod that shows a length of 520.5 mm, a few millimetres less than the Egyptian cubit.[8] A slate measuring rod was also found, divided into fractions of a Royal Cubit and dating to the time of Akhenaten.[9]

Further cubit rods have been found in the tombs of officials. Two examples are known from the tomb of Maya—the treasurer of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun—in Saqqara. Another was found in the tomb of Kha (TT8) in Thebes. These cubits are ca 52.5 cm (20.7 in) long and are divided into seven palms, each palm is divided into four fingers and the fingers are further subdivided.[10] Another wooden cubit rod was found in Theban tomb TT40 (Huy) bearing the throne name of Tutankhamun (Nebkheperure).[11]

Egyptian measuring rods also had marks for the Remen measurement of approximately 370 mm (15 in), used in construction of the Pyramids.[12][13]

Ancient Europe

An oak rod from the Iron Age fortified settlement at Borre Fen in Denmark measured 53.15 inches (135.0 cm), with marks dividing it up into eight parts of 6.64 inches (16.9 cm), corresponding quite closely to half a Doric Pous (a Greek foot).[14] A hazel measuring rod recovered from a Bronze Age burial mound in Borum Eshøj, East Jutland by P. V. Glob in 1875 measured 30.9 inches (78 cm) corresponding remarkably well to the traditional Danish foot.[15] The megalithic structures of Great Britain has been hypothesized to have been built by a "Megalithic Yard", though some authorities believe these structures have been measured out by pacing.[16][17][18] Several tentative Bronze Age bone fragments have been suggested as being parts of a measuring rod for this hypothetical measurement.[16]

Roman Empire

Large public works and imperial expansion, particularly the large network of Roman roads and the many milecastles, made the measuring rod an indispensable part of both the military and civilian aspects of Roman life. Republican Rome used several measures, including the various Greek feet measurements and the Oscan foot of 23.7 cm.[19] Standardisation was introduced by Agrippa in 29 BC, replacing all previous measurements by a Roman foot of 29.6 cm, which became the foot of Imperial Rome.[20]

The Roman measuring rod was 10 Roman feet long, and hence called a decempeda, Latin for 'ten feet'. It was usually of square section capped at both ends by a metal shoe, and painted in alternating colours. Together with the groma and dioptra the decempeda formed the basic kit for the Roman surveyors.[21] The measuring rod is frequently found depicted in Roman art showing the surveyors at work. A shorter folding yardstick one Roman foot long is known from excavations of a Roman fort in Niederburg, Germany.[22]

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, bars were used as standards of length when surveying land.[23] These bars often used a unit of measure called a rod, of length equal to 5.5 yards, 5.0292 metres, 16.5 feet, or 1⁄320 of a statute mile.[24] A rod is the same length as a perch or a pole.[25] In Old English, the term lug is also used. The length is equal to the standardized length of the ox goad used for teams of eight oxen by medieval English ploughmen.[26] The lengths of the perch (one rod unit) and chain (four rods) were standardized in 1607 by Edmund Gunter. [27] The rod unit was still in use as a common unit of measurement in the mid-19th century, when Henry David Thoreau used it frequently when describing distances in his work Walden.

In culture

Iconography

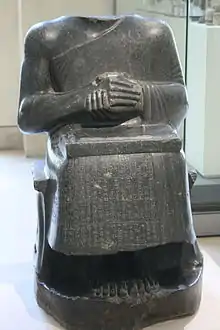

Two statues of Gudea of Lagash in the Louvre depict him sitting with a tablet on his lap, upon which are placed surveyors tools including a measuring rod.[29]

Seal 154 recovered from Alalakh, now in the Biblioteque Nationale show a seated figure with a wedge shaped measuring rod.[30]

The Tablet of Shamash recovered from the ancient Babylonian city of Sippar and dated to the 9th century BC shows Shamash, the Sun God awarding the measuring rod and coiled rope to newly trained surveyors.[31][32]

A similar scene with measuring rod and coiled rope is shown on the top part of the diorite stele above the Code of Hammurabi in the Louvre, Paris, dating to ca. 1700 BC.[33]

The "measuring rod" or tally stick is common in the iconography of Greek Goddess Nemesis.[34]

The Graeco-Egyptian God Serapis is also depicted in images and on coins with a measuring rod in hand and a vessel on his head.[35][36]

The most elaborate depiction is found on the Ur-Nammu-stela, where the winding of the cords has been detailed by the sculptor. This has also been described as a "staff and a chaplet of beads".[37]

Mythology

The myth of Inanna's descent to the nether world describes how the goddess dresses and prepares herself:

She held the lapis-lazuli measuring rod and measuring line in her hand.[38]

Lachesis in Greek mythology was one of the three Moirai (or Fates) and "allotter" (or drawer of lots). She measured the thread of life allotted to each person with her measuring rod. Her Roman equivalent was Decima (the 'Tenth').[39]

Varuna in the Rigveda, is described as using the Sun as a measuring rod to lay out space in a creation myth.[40][41] W. R. Lethaby has commented on how the measurers were seen as solar deities and noted how Vishnu "measured the regions of the Earth".[42]

Bible

Measuring rods or reeds are mentioned many times in the Bible.

A measuring rod and line are seen in a vision of Yahweh in Ezekiel 40:2-3:

In visions of God he took me to the land of Israel and set me on a very high mountain, on whose south side were some buildings that looked like a city. He took me there, and I saw a man whose appearance was like bronze; he was standing in the gateway with a linen cord and a measuring rod in his hand.[43]

Another example is Revelation 11:1:

I was given a reed like a measuring rod and was told, "Go and measure the temple of God and the altar, and count the worshipers there".[43]

The measuring rod also appears in connection with foundation stone rites in Revelation 21:14-15:

And the wall of the city had twelve foundation stones, and on them were the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb. The one who spoke with me had a gold measuring rod to measure the city, and its gates and its wall.[44]

See also

References

- American Society of Civil Engineers (1891). Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. American Society of Civil Engineers.

- Scandinavian Archaeometry Center (1993). Archaeology and natural science, p. 118. P. Åströms. ISBN 9789170810824. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Whitelaw, page 14

- Whitelaw, page 15

- S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 39–40.

- Gang Zhao (1986). Man and land in Chinese history: an economic analysis, p. 65. Stanford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-8047-1271-2.

- Lepsius, Richard (1865). Die altaegyptische Elle und ihre Eintheilung (in German). Berlin: Dümmler.

- Acta praehistorica et archaeologica. B.Hessling. 1976.

- Broadman & Holman Publishers (15 September 2006). Holman Illustrated Study Bible-HCSB. B&H Publishing Group. p. 1413. ISBN 978-1-58640-275-4. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Marshall Clagett, Ancient Egyptian Science, A Source Book. Volume Three: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics, American Philosophical Society, 1999

- Frances Welsh (2008). Tutankhamun's Egypt. Osprey Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7478-0665-3.

- Acta archaeologica. Levin & Munksgaard. 1969. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Martin Brennan (1980). The Boyne Valley vision. Dolmen Press. ISBN 978-0-85105-362-2.

- Tauber, H. (1964): Copenhagen radiocarbon dates VI, Radiocarbon no. 6, pp 215-25.

- Boye, V. (1896): Fund av Egekister fra Bronzealderen i Danmark. Et monografisk Bidrag til Belysning af Bronzealderens Kultur. Kopenhagen.

- Margaret Ponting (2003). "Megalithic Callanish". In Clive Ruggles (ed.). Records in Stone: Papers in Memory of Alexander Thom. Cambridge University Press. pp. 423–441. ISBN 978-0-521-53130-6.

- Heggie, Douglas C. (1981). Megalithic Science: Ancient Mathematics and Astronomy in North-west Europe. Thames and Hudson. p. 58. ISBN 0-500-05036-8.

- David George Kendall; F. R. Hodson; Royal Society (Great Britain); British Academy (1974). The Place of astronomy in the ancient world: a joint symposium of the Royal Society and the British Academy, Hunting Quanta, p. 258. Oxford University Press for the British Academy. ISBN 978-0-19-725944-3.

- Klein, Herbert Arthur; The World of Measurements, Simon and Schuster, 1976

- Soren, D. & Soren, N. (1999): A Roman villa and a late Roman infant cemetery : excavation at Poggio Gramignano, Lugnano in Teverina. Bibliotheca archaeologica (Rome, Italy), no. 23. L'Erma di Bretschneider, Rome p 184 from Google books

- Shuttleworth, M. "Building Roman roads". Experiment-resources.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Main Limes Museum: Measuring rod

- Charles Blaney Breed; George Leonard Hosmer (1977). The principles and practice of surveying. Wiley.

- Rowlett, Russ (25 April 2002). "rod (rd) [1]". How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Bonten, JHM (19 January 2007). "Anglo-Saxon and Biblical to Metrics Conversions". Surveyor + Chain + British-Nautical. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Rowlett, Russ (15 December 2008). "lug". How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- "Rod, unit of measure". UnitConversion.org. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Judith Resnik, Dennis Curtis, Representing Justice: Invention, Controversy, and Rights in City-States and Democratic Courtrooms, Yale University Press, 2011

- Donald Preziosi (1983). Minoan architectural design: formation and signification, p. 498. Mouton. ISBN 978-90-279-3409-3.

- Dominique Collon (1975). The seal impressions from Tell Atchana/Alalakh. Butzon & Bercker. ISBN 978-3-7887-0469-8.

- The British Museum - Tablet of Shamash

- William Rainey Harper; Ernest De Witt Burton; Shailer Mathews (1905). The Biblical world p. 120. University of Chicago Press.

- Amélie Kuhrt (1995). The ancient Near East, c. 3000-330 BC. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

- Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: a study of religious interaction in Roman Syria p. 329. BRILL. p. 329. ISBN 978-90-04-11589-7.

- Johann Joachim Eschenburg (1836). Manual of classical literature. Key and Biddle. pp. 343–. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Maarten Jozef Vermaseren; International Association for the History of Religions. Dutch Section (1979). Studies in Hellenistic religions. Brill Archive. p. 199. ISBN 978-90-04-05885-9.

- Jeremy Black, Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, Rod and Ring, p 156.

- cf. Inana's descent to the nether world line 25. The Sumerian has: gi-diš-nindan eš2-gana2 za-gin3 šu ba-ni-in-du8 i.e. taken literally the rod would have the length of one nindan (6 cubit = 5.94m) and the eš2-gana2 the surveyor's line - would be ten nindan in length.

- Robert Graves (1957). The Greek myths, p. 30. G. Braziller.

- Rig Veda, Book 5, Hymn 85, Verse 5 tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith, [1896], at sacred-texts.com

- Edward Washburn Hopkins (2007). The Religions of India. Echo Library. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4068-1329-6.

- W. R. Lethaby (December 2005). Architecture, Mysticism and Myth. Cosimo, Inc. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-59605-380-9. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- BIBLE: New International Version. 1984.

- Foundation Publication Inc (1 March 1997). New American Standard Bible. Foundation Publications, publisher for the Lockman Foundation. ISBN 9781885217684. Retrieved 8 April 2011.