Tick mattress

A tick mattress, bed tick or tick is a large bag made of strong, stiff, tightly-woven material[1] (ticking). This is then filled to make a mattress, with material such as straw, chaff, horsehair, coarse wool or down feathers,[2]: 674-5 vol1 and less commonly, leaves, grass, reeds, bracken, or seaweed.[3] The whole stuffed mattress may also, more loosely, be called a tick. The tick mattress may then be sewn through to hold the filling in place, or the unsecured filling could be shaken and smoothed as the beds were aired each morning.[4] A straw-filled bed tick is called a paillasse, palliasse, or pallet, and these terms may also be used for bed ticks with other fillings. A tick filled with flock (loose, unspun fibers, traditionally of cotton or wool) is called a flockbed. A feather-filled tick is called a featherbed, and a down-filled one a downbed; these can also be used above the sleeper, as a duvet.[4][5]

A tick mattress (or a pile of such tick mattresses, softest topmost, and the sheets, bedcovers, and pillows), was what Europeans traditionally called a "bed". The bedframe, when present, supported the bed, but was not considered part of it.[2]: 674-5 vol1

History

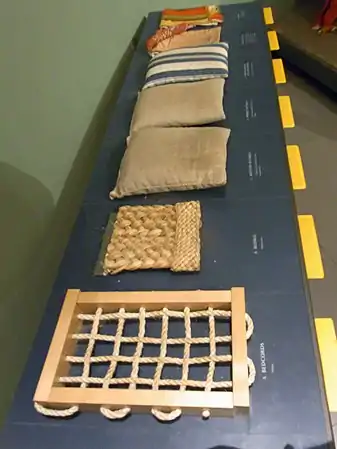

Touchable museum samples illustrating a 1590s bed: the bedcords, plaited-rush[6] bedmat, a flockbed and a featherbed in dun ticking, a downbed in striped ticking, and the bedlinen.[5]

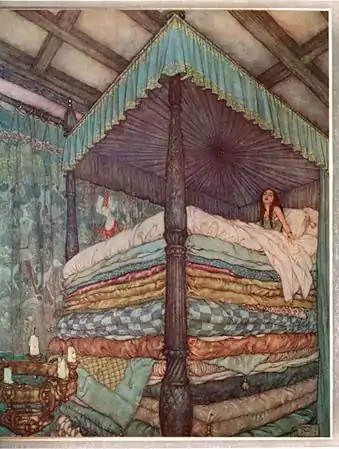

Touchable museum samples illustrating a 1590s bed: the bedcords, plaited-rush[6] bedmat, a flockbed and a featherbed in dun ticking, a downbed in striped ticking, and the bedlinen.[5] The fairytale The Princess and the Pea exaggerates the traditional European layering of tick mattresses

The fairytale The Princess and the Pea exaggerates the traditional European layering of tick mattresses%252C_late_19th_century_(CH_1108827543).jpg.webp)

In the fifteenth century, most people in Europe slept on straw, but very rich people had featherbeds on top (for instance, Anne of Brittany's ladies in waiting slept on straw beds). By the nineteenth century many people had feather beds.[3][4]

If the pile of mattresses threatened to slide off the bed, in 16th- and 17th-century England it was restrained with bedstaves, vertical poles thrust into the frame. A broad step might be placed alongside the bed, as a place to sit and as a step up onto the pile of bedclothes.[5]

Bedticks were often aired, often by hanging them outdoors, as bedding is still aired in parts of Europe and in East Asia. In English-speaking cultures, however, airing bedding outdoors came to be seen as a foreign practice, with 19th-century housekeeping manuals giving methods of airing beds inside, and disparaging airing them in the window as "German-style".[4]

Stuffings

Straw and hay are cheap and abundant stuffings. The chaff of a local grain, be it rice chaff or oat chaff, is softer but less abundant. Reeds, bracken, seaweed, and esparto grass have also been used.[3] Horsehair and flock make for firmer beds.[4] Rags have also been used.[7]

Before recycled cotton cloth was widely available in Japan, commoners slept upon kami busuma, stitched crinkled paper stuffed with fibers from beaten dry straw, cattails, or silk waste, on top of mushiro straw floor mats. Cotton was introduced from Korea in the 15th century, but did not become widely available throughout Japan until the mid-eighteenth; commoners continued to rely on wild and cultivated bast fibers.[8] Later, futon ticks were made with patchwork recycled cotton, quilted together and filled with bast fiber.[9] Later still, they were filled with cotton, mattresses and coverlets both. Wool and synthetics are now also used.[10]

Leaves can be used to fill ticks; they vary in quality by species and time of year. Chestnut-leaves are prone to rustle, and were therefore called parliament-beds in 17th-century France. Beech leaves were a quieter stuffing; if harvested in autumn before they were "much frostbitten", stayed soft and loose and did not become musty for seven or eight years, far longer than straw.[11] Beech-leaf beds were also said to smell of green tea and crackle slightly, and be as soft an elastic as maize-husk beds.[3]

Swapping out the stuffing was often done seasonally, as materials became available. Travellers might carry ticks, but not the stuffing, buying whatever filling was cheap locally.[3]

For expensive fillings, like feathers, the feathers would outlast the tick, and be transferred into a new tick when they began to poke through old one.[12] Featherbeds may be washed intact, or feathers and tick can be cleaned separately.[13] Since featherbeds were historically very valuable, and the feathers often took years to collect, they were not simply discarded and replaced. Indeed, they were taken along by migrants and mentioned in wills.[4] Featherbeds were often made with feathers saved from poultry plucked for eating (servants were often allowed to keep the feathers they plucked). It took about 50 pounds (23 kg) to fill a tick. Goose and duck feathers were most valued (chicken feathers were undesirable), and down was softer and more valuable than other feathers.[3][4]

Tufting and quilting

To hold the filling in place, either sturdy individual securing stitches can be made through the tick and the filling (tufting), or the mattress can be quilted with lines of stitches.[14] Both techniques are also used decoratively.[7][14]

Individual tufting stitches for stronger materials and harder fillings are made with a stronger thread or twine. An extra-long upholstery needle may be needed to pass the thread through the tick easily. Sometimes the stitches are finished with buttons on each side (often covered buttons).[7]

Mattress quilting is done in a variety of patterns.[15] Denser stitching makes the mattress firmer.[16]

.jpg.webp) A tufted mattress, with through-stitches securing the filling

A tufted mattress, with through-stitches securing the filling_(page_14_crop).jpg.webp) A similar untufted mattress

A similar untufted mattress.jpg.webp) The pink tartan shikibutons are through-quilted; the green kakebutons may be quilted, but seem to still be in their covers.

The pink tartan shikibutons are through-quilted; the green kakebutons may be quilted, but seem to still be in their covers.

Unsewn ticking sheets

A bed filled with loose straw, but without the bedding, at a museum in Denmark

A bed filled with loose straw, but without the bedding, at a museum in Denmark.jpg.webp) Basic straw mattresses in a loft in a historic site in Nova Scotia, Canada

Basic straw mattresses in a loft in a historic site in Nova Scotia, Canada

The lowest layer might be covered with a length of ticking instead of stuffed into a tick, which made it easier to change. Henry VII of England's bed had a lower layer of loose straw:[3]

The groom of the wardrobe brings in the loose straw and lays it reverently at the foot of the bed. The gentleman-usher draws back the curtains. Two squires stand by the bedhead and two yeomen of the guard at the foot. One of these, with the help of the yeomen of the chamber, carefully forms the truss, and rolls up and down on it to make it smooth and ensure that no dagger or such are hidden in it....A canvas is laid over the straw, then the feather-bed, which is smoothed with a bedstaff.

— Wright, Lawrence (1962). Warm & Snug:The History of the Bed. Routledge & K.Paul.[4]

Such simple beds were also used as the only mattress

"That is capital," said her grandfather; "now we must put on the sheet, but wait a moment first," and he went and fetched another large bundle of hay to make the bed thicker, so that the child should not feel the hard floor under her--"there, now bring it here." Heidi had got hold of the sheet, but it was almost too heavy for her to carry; this was a good thing, however, as the close thick stuff would prevent the sharp stalks of the hay running through and pricking her. The two together now spread the sheet over the bed, and where it was too long or too broad, Heidi quickly tucked it in under the hay. It looked now as tidy and comfortable a bed as you could wish for, and Heidi stood gazing thoughtfully at her handiwork.

"We have forgotten something now, grandfather," she said after a short silence.

"What's that?" he asked.

"A coverlid; when you get into bed, you have to creep in between the sheets and the coverlid."

"Oh, that's the way, is it? But suppose I have not got a coverlid?" said the old man.

"Well, never mind, grandfather," said Heidi in a consoling tone of voice, "I can take some more hay to put over me," and she was turning quickly to fetch another armful from the heap, when her grandfather stopped her. "Wait a moment," he said, and he climbed down the ladder again and went towards his bed. He returned to the loft with a large, thick sack, made of flax, which he threw down, exclaiming, "There, that is better than hay, is it not?"

Heidi began tugging away at the sack with all her little might, in her efforts to get it smooth and straight, but her small hands were not fitted for so heavy a job. Her grandfather came to her assistance, and when they had got it tidily spread over the bed, it all looked so nice and warm and comfortable that Heidi stood gazing at it in delight.

— Spyri, Johanna (1881). Heidi. Translated by an unspecified translator (Project Gutenberg ebook 1448 ed.)., a novel

See also

References

- John Wilson Browne (1884), Hardware: how to buy it for foreign markets, p. 235

- Dictionnaire de l'ameublement et de la décoration depuis le XIIIe siècle jusqu'à nos jours, Havard, Henry, 1838-1921

- "Straw mattresses, chaff beds, palliasses, ticks stuffed with leaves". www.oldandinteresting.com. 9 January 2008.

- "Featherbeds, duvets, eiderdowns, feather ticks - history". www.oldandinteresting.com. 2006.

- Vredeman de Vries, Hans (September 28, 1998). "Great Bed of Ware". Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections. V&A Explore The Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum.

- "East Anglian rush", probably actually Scirpus, a sedge

- Johnson, Liz (16 June 2016). "A Tufting Tutorial". Sew4Home. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- Dusenbury, Mary (1992). "A WISTERIA GRAIN BAG and other tree bast fiber textiles of Japan". Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Wada, Yoshiko (2004-01-01). Boro no Bi : Beauty in Humility—Repaired Cotton Rags of Old Japan. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings.

- Hones, Jenny Nakao. "The Pros and Cons of the Japanese Futon – Asian Lifestyle Design". Asian Lifestyle Design. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Evelyn, John; Nisbet, John (1706). Sylva; Or, A Discourse of Forest Trees. Vol. 1.

The leaves of the chesnut-tree make very wholsom mattresses to lie on, and they are good littier for cattel: But those leafy-beds, for the crackling noise they make when one turns upon them, the French call licts de Parliament... Of the Beech... its very leaves (which make a natural and most agreeable canopy all the summer) being gathered about the fall, and somewhat before they are much frostbitten, afford the best and easiest mattrasses in the world to lay under our quilts instead of straw; because, besides their tenderness and loose lying together, they continue sweet for seven or eight years long, before which time straw becomes musty and hard; they are thus used by divers persons of quality in Dauphine; and in Swizzerland I have sometimes lain on them to my great refreshment; so as of this tree it may properly be said,

The wood's an house; the leaves a bed.[footnote:]..........Silva domus, cubilia frondes. Juvenal. - Montgomery, L. M. (Lucy Maud). Anne of Avonlea.

I'm going to shift the feathers from my old bedtick to the new one. I ought to have done it long ago but I've just kept putting it off . . . it's such a detestable task... Any one who has ever shifted feathers from one tick to another will not need to be told that when Anne finished she was a sight to behold. Her dress was white with down and fluff, and her front hair, escaping from under the handkerchief, was adorned with a veritable halo of feathers.

- Question Box. How make bread with soya flour? How waterproof garments? How clean feather pillows?. Homemakers' chat. United States Department of Agriculture Radio Service. 28 November 1944.

A homemaker writes, "We've had sickness in the family. I'd like to clean the feather pillows. Is it possible to wash them?["]

Home management specialists of the U. S. Department of Agriculture say that you may wash pillows with the feathers in them if you wish. Or you may remove the feathers, from the ticking, put them in a large muslin bag and wash the bag of feathers and the ticking separately.

Whether you wash the feathers in the ticking or put them in a muslin bag, the method of washing is the same. Use warm water with lots of suds. And scrub the pillow of bag of feathers with a weak washing soda solution.

You can tell whether you need to put the pillows through a second suds. You will need to rinse them two or three times. Use lukewarm water. And squeeze the water out. Then let the pillows dry in warm air and in sun, if possible. During the drying process, beat the pillows two or three times so they will be fluffy.

If you wash the feathers and ticking separately, starch the ticking so the feathers won't work through. Make a good stiff starch and apply it to the inside of the ticking with a sponge or a soft cloth. This will act as a seal or coating to the ticking and the feathers won't work through. - "What Is Mattress Tufting?". Gardner Mattress. 26 January 2018.

- "Quilting Archives". Atlanta Attachment Co.

- "Quilting". Dubuque Mattress Factory.