Panthéon

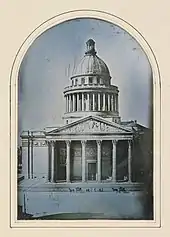

The Panthéon (French: [pɑ̃.te.ɔ̃] ⓘ, from the Classical Greek word πάνθειον, pántheion, '[temple] to all the gods')[1] is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, in the centre of the Place du Panthéon, which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 and 1790, from designs by Jacques-Germain Soufflot, at the behest of King Louis XV of France; the king intended it as a church dedicated to Saint Genevieve, Paris's patron saint, whose relics were to be housed in the church. Neither Soufflot nor Louis XV lived to see the church completed.

| Panthéon | |

|---|---|

The Panthéon | |

| Former names | Église Sainte-Geneviève |

| General information | |

| Type | Mausoleum |

| Architectural style | Neoclassicism |

| Location | Place du Panthéon Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48°50′46″N 2°20′45″E |

| Construction started | 1758 |

| Completed | 1790 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Jacques-Germain Soufflot Jean-Baptiste Rondelet |

| Website | |

| https://www.paris-pantheon.fr/en/ | |

| Designated | 1920 |

| Reference no. | PA00088420 |

By the time the construction was finished, the French Revolution had started; the National Constituent Assembly voted in 1791 to transform the Church of Saint Genevieve into a mausoleum for the remains of distinguished French citizens, modelled on the Pantheon in Rome which had been used in this way since the 17th century. The first panthéonisé was Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, although his remains were removed from the building a few years later. The Panthéon was twice restored to church usage in the course of the 19th century—although Soufflot's remains were transferred inside it in 1829—until the French Third Republic finally decreed the building's exclusive use as a mausoleum in 1881. The placement of Victor Hugo's remains in the crypt in 1885 was its first entombment in over 50 years.

The successive changes in the Panthéon's purpose resulted in modifications of the pedimental sculptures and the capping of the dome by a cross or a flag; some of the originally existing windows were blocked up with masonry in order to give the interior a darker and more funereal atmosphere,[2] which compromised somewhat Soufflot's initial attempt at combining the lightness and brightness of the Gothic cathedral with classical principles.[3] The architecture of the Panthéon is an early example of Neoclassicism, surmounted by a dome that owes some of its character to Bramante's Tempietto.

In 1851, Léon Foucault conducted a demonstration of diurnal motion at the Panthéon by suspending a pendulum from the ceiling, a copy of which is still visible today. As of December 2021 the remains of 81 people (75 men and six women) had been transferred to the Panthéon.[4] More than half of all the panthéonisations were made under Napoleon's rule during the First Empire.

History

Site and earlier buildings

The site of the Panthéon had great significance in Paris history, and was occupied by a series of monuments. It was on Mount Lucotitius, a height on the Left Bank where the forum of the Roman town of Lutetia was located. It was also the original burial site of Saint Genevieve, who had led the resistance to the Huns when they threatened Paris in 451. In 508, Clovis, King of the Franks, constructed a church there, where he and his wife were later buried in 511 and 545. The church, originally dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul, was rededicated to Saint Genevieve, who became the patron saint of Paris. It was at the centre of the Abbey of Saint Genevieve, a centre of religious scholarship in the Middle Ages. Her relics were kept in the church, and were brought out for solemn processions when dangers threatened the city.[5]

Construction

.png.webp) Soufflot's original plan for the Church of Sainte Genevieve (1756)

Soufflot's original plan for the Church of Sainte Genevieve (1756) Soufflot's final plan: the principal façade (1777)

Soufflot's final plan: the principal façade (1777) Soufflot's plan of the three domes, one within another

Soufflot's plan of the three domes, one within another Looking upward at the first and second domes

Looking upward at the first and second domes Iron rods were used to give greater strength and stability to the stone structure (1758–90)

Iron rods were used to give greater strength and stability to the stone structure (1758–90)

King Louis XV vowed in 1744 that if he recovered from his illness he would replace the dilapidated church of the Abbey of St Genevieve with a grander building worthy of the patron saint of Paris. He did recover, but ten years passed before the reconstruction and enlargement of the church was begun. In 1755 The Director of the King's public works, Abel-François Poisson, marquis de Marigny, chose Jacques-Germain Soufflot to design the church. Soufflot (1713–1780) had studied classical architecture in Rome over 1731–38. Most of his early work was done in Lyon. Saint Genevieve became his life's work; it was not finished until after his death.[6]

His first design was completed in 1755, and was clearly influenced by the work of Bramante he had studied in Italy. It took form of a Greek cross, with four naves of equal length, and monumental dome over the crossing in the centre, and a classical portico with Corinthian columns and a peristyle with a triangular pediment on the main façade.[7] The design was modified five times over the following years, with the addition of a narthex, a choir, and two towers. The design was not finalised until 1777.[8]

The foundations were laid in 1758, but due to economic problems work proceeded slowly. In 1780, Soufflot died and was replaced by his student Jean-Baptiste Rondelet. The re-modelled Abbey of St. Genevieve was finally completed in 1790, shortly after the beginning of the French Revolution.

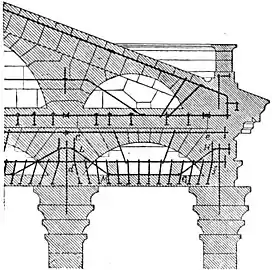

The building is 110 metres long by 84 metres wide, and 83 metres high, with the crypt beneath of the same size. The ceiling was supported by isolated columns, which supported an array of barrel vaults and transverse arches. The massive dome was supported by pendentives rested upon four massive pillars. Critics of the plan contended that the pillars could not support such a large dome. Soufflot strengthened the stone structure with a system of iron rods, a predecessor of modern reinforced buildings. The bars had deteriorated by the 21st century, and a major restoration project to replace them was carried out between 2010 and 2020.[9]

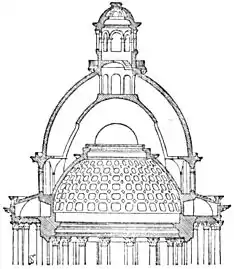

The dome is actually three domes, fitting within each other. The first, lowest dome, has a coffered ceiling with rosettes, and is open in the centre. Looking through this dome, the second dome is visible, decorated with the fresco The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve by Antoine Gros. The outermost dome, visible from the outside, is built of stone bound together with iron cramps and covered with lead sheathing, rather than of carpentry construction, as was the common French practice of the period. Concealed buttresses inside the walls give additional support to the dome.[10]

The Revolution – The "Temple of the Nation"

.jpg.webp) The Tomb of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The Tomb of Jean-Jacques Rousseau The Panthéon in 1795. The façade windows were bricked up to make the interior darker and more solemn.

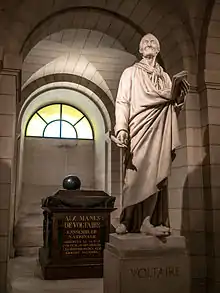

The Panthéon in 1795. The façade windows were bricked up to make the interior darker and more solemn. Tomb and statue of Voltaire

Tomb and statue of Voltaire Transfer of ashes of Voltaire to the Pantheon (1791)

Transfer of ashes of Voltaire to the Pantheon (1791)

The Church of Saint Genevieve was nearly complete, with only the interior decoration unfinished, when the French Revolution began in 1789. In 1790, the Marquis de Vilette proposed that it be made a temple devoted to liberty, on the model of the Pantheon in Rome. "Let us install statues of our great men and lay their ashes to rest in its underground recesses."[11] The idea was formally adopted in April, 1791, after the death of the prominent revolutionary figure, The Comte de Mirabeau, the President of the National Constituent Assembly on April 2, 1791. On April 4, 1791, the Assembly decreed "that this religious church become a temple of the nation, that the tomb of a great man become the altar of liberty." They also approved a new text over the entrance: "A grateful nation honors its great men." On the same day the declaration was approved, the funeral of Mirabeau was held in the church.[11]

The ashes of Voltaire were placed in the Panthéon in a lavish ceremony on 11 July 1791, followed by the remains of several revolutionaries, including Jean-Paul Marat, replacing Mirabeau and of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In the rapid shifts of power of the Revolutionary period, two of the first men honored in Pantheon, Mirabeau and Marat, were declared enemies of the Revolution, and their remains were removed. Finally, the new government of the French Convention decreed in February, 1795 that no one should be placed in the Pantheon who had not been dead at least ten years.[12]

Soon after the church was transformed into a mausoleum, the Assembly approved architectural changes to make the interior darker and more solemn. The architect Quatremère de Quincy bricked up the lower windows and frosted the glass of the upper windows to reduce the light, and removed most of the ornament from the exterior. The architectural lanterns and bells were removed from the façade. All of the religious friezes and statues were destroyed in 1791; it was replaced by statuary and murals on patriotic themes.[12]

Temple to church and back to temple (1806–1830)

Napoleon Bonaparte, when he became First Consul in 1801, signed a Concordat with the Pope, agreeing to restore former church properties, including the Panthéon. The Panthéon was under the jurisdiction of the canons of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. Celebrations of important events, such as the victory of Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz, were held there. However, the crypt of the church kept its official function as the resting place for illustrious Frenchmen. A new entrance directly to the crypt was created via the eastern porch (1809–1811). The artist Antoine-Jean Gros was commissioned to decorate the interior of the cupola. It combined the secular and religious aspects of the church; it showed the Genevieve being conducted to heaven by angels, in the presence of great leaders of France, from Clovis I and Charlemagne to Napoleon and the Empress Josephine.

During the reign of Napoleon, the remains of forty-one illustrious Frenchmen were placed in the crypt. They were mostly military officers, senators and other high officials of the Empire, but also included the explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville and the painter Joseph-Marie Vien, the teacher of Napoleon's official painter, Jacques-Louis David.[13]

During the Bourbon Restoration which followed the fall of Napoleon, in 1816 Louis XVIII of France restored the entire Panthéon, including the crypt, to the Catholic Church. The church was also at last officially consecrated in the presence of the King, a ceremony which had been omitted during the Revolution. The sculpture on the pediment by Jean Guillaume Moitte, called The Fatherland crowning the heroic and civic virtues was replaced by a religious-themed work by David d'Angers. The reliquary of Saint Genevieve had been destroyed during the Revolution, but a few relics were found and restored to the church (They are now in the neighboring Church of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont). In 1822 François Gérard was commissioned to decorate the pendentives of the dome with new works representing Justice, Death, the Nation, and Fame. Jean-Antoine Gros was commissioned to redo his fresco on the inner dome, replacing Napoleon with Louis XVIII, as well as figures of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The new version of the cupola was inaugurated in 1824 by Charles X. As to the crypt where the tombs were located, it was locked and closed to visitors.[14]

Under Louis Philippe I, the Second Republic and Napoleon III (1830–1871)

The French Revolution of 1830 placed Louis Philippe I on the throne. He expressed sympathy for Revolutionary values, and on 26 August 1830, the church once again became the Pantheon. However, the crypt remained closed to the public, and no new remains were added. The only change made was to the main pediment, which had been remade with a radiant cross; it was remade again by D'Angers with a patriotic work called The Nation Distributing Crowns Handed to Her by Liberty, to Great Men, Civil and Military, While History Inscribes Their Names.

Louis Philippe was overthrown in 1848 and replaced by the elected government of the Second French Republic, which valued revolutionary themes. The new government designated the Pantheon "The Temple of Humanity", and proposed to decorate it with sixty new murals honouring human progress in all fields. In 1851 the Foucault Pendulum of astronomer Léon Foucault was hung beneath the dome to illustrate the rotation of the earth. However, on complaints from the Church, it was removed in December of the same year.

Louis Napoléon, nephew of the Emperor, was elected President of France in December 1848, and in 1852 staged a coup-d'état and made himself Emperor. Once again the Pantheon was returned to the church, with the title of "National Basilica". The remaining relics of Saint Genevieve were restored to the church, and two groups of sculpture commemorating events in the life of the Saint were added. The crypt remained closed.

The Third Republic (1871–1939)

Saint Genevieve bringing supplies to Paris by Puvis de Chavannes (1874)

Saint Genevieve bringing supplies to Paris by Puvis de Chavannes (1874) Christ Showing the Angel of France the Destiny of Her People, mosaic by Antoine-Auguste-Ernest Hébert

Christ Showing the Angel of France the Destiny of Her People, mosaic by Antoine-Auguste-Ernest Hébert The National Convention by François-Léon Siccard (1921)

The National Convention by François-Léon Siccard (1921) Victory leading the Armies of the Republic by Edouard Detaille (1905)

Victory leading the Armies of the Republic by Edouard Detaille (1905)

The Basilica suffered damage from German shelling during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. During the brief reign of the Paris Commune in May 1871, it suffered more damage during fighting between the Commune soldiers and the French Army. During the early years of the Third Republic, under conservative governments, it functioned as a church, but the interior walls were largely bare. Beginning in 1874, The interior was redecorated with new murals and sculptural groups linking French history and the history of the church, by notable artists including Puvis de Chavannes and Alexandre Cabanel, and the artist Antoine-Auguste-Ernest Hébert, who made a mosaic under the vault of the apsidal chapel called Christ Showing the Angel of France the Destiny of Her People.[15]

In 1881, a decree was passed to transform the Church of Saint Genevieve into a mausoleum again. Victor Hugo was the first to be placed in the crypt afterwards. The subsequent governments approved the entry of literary figures, including the writer Émile Zola (1908), and, after World War I, leaders of the French socialist movement, including Léon Gambetta (1920) and Jean Jaurès (1924). The Third Republic governments also decreed that the building should be decorated with sculpture representing "the golden ages and great men of France." The principal works remaining from this period include the sculptural group called The National Assembly, commemorating the French Revolution; a statue of Mirabeau, the first man interred in the Pantheon, by Jean-Antoine Ingabert; (1889–1920); and two patriotic murals in the apse Victory Leading the Armies of the Republic to Towards Glory by Édouard Detaille, and Glory Entering the Temple, Followed by Poets, Philosophers, Scientists and Warriors , by Marie-Désiré-Hector d'Espouy (1906).[15]

1945–present

The short-lived Fourth Republic (1948–1958) following World War II pantheonized two physicists, Paul Langevin and Jean Perrin; a leader of the abolitionist movement, Victor Schœlcher; early leader of Free France and colonial administrator Félix Éboué; and Louis Braille, inventor of the Braille writing system, in 1952.

Under the Fifth Republic of President Charles de Gaulle, the first person to be buried in the Panthéon was the Resistance leader Jean Moulin. Modern figures buried in recent years include Nobel Peace Prize winner René Cassin (1987) known for drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Jean Monnet who was a moving force in the creation of the ECSC, the forerunner of the EU, was interred in the 100th anniversary of his birth; Nobel laureates physicists and chemists Marie Curie and Pierre Curie (1995); the writer and culture minister André Malraux (1996); and the lawyer, politician Simone Veil (2018).[16] In 2021, Josephine Baker was inducted into the Pantheon, becoming the first Black woman to receive that honor.[17]

Architecture and art

Dome

The final plan of the dome was accepted in 1777, and it was completed in 1790. It was designed to rival those of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and St Paul's Cathedral in London. Unlike the dome of Les Invalides in Paris, which has a wooden framework, the dome is constructed entirely of stone. It is actually three domes, one within the other, with the painted ceiling, visible from below, on the second dome. The dome is 83.0 metres (272 ft) high, compared with the tallest dome in the world, St. Peter's Basilica at 136.57 metres (448.1 ft).

Dome

Dome The Panthéon represented with a statue of Fame at its top

The Panthéon represented with a statue of Fame at its top The present-day cross atop the roof lantern

The present-day cross atop the roof lantern

The dome is capped by a cross. However, a statue of Saint Genevieve was initially supposed to sit at the top of the dome. A cross was put temporarily in 1790. After the transformation into a mausoleum in 1791, it was planned that the cross would be replaced by a statue representing Fame. The project was however abandoned. Between 1830 and 1851, a flag was put instead. The cross returned after Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte restored the building to church use. The cross was replaced with a red flag during the Paris Commune in 1871. A cross returned subsequently.

The fresco by Gros seen from inside the dome

The fresco by Gros seen from inside the dome The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve, in the dome by Antoine-Jean Gros (1811–1834)

The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve, in the dome by Antoine-Jean Gros (1811–1834)

Looking up from the crossing of the transept beneath the dome, the painting by Jean-Antoine Gros, the Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve (1811–1834), is visible through the opening in the lowest cupola. The triangle in the center symbolizes the Trinity, surrounded by a halo of light. The Hebrew characters spell the name of God. The only character seen in full is Saint Genevieve herself, seated on a rocky promontory. The groups around the painting, made during the Restoration of the Monarchy, represent Kings of France who played an important role in protecting the church. To the left of Saint Genevieve is a group including Clovis, the first King to convert to Christianity. The second group is centred around Charlemagne, who created the first universities. The third group is centred around Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis, with the Crown of Thorns which he brought back from the Holy Land to place in the church of Sainte-Chapelle. The last group is centred around Louis XVIII, the last King of the Restoration, and his niece, looking up into the clouds at the martyred Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. The angels in the scene are carrying the Chartre, the document by which Louis XVIII re-established the church after the French Revolution.[18]

The four pendentives, or arches, which support the dome are decorated with paintings from the same period by François Gérard depicting Glory, Death, The Nation and Justice (1821–37).

Façade, peristyle and entrance

.jpg.webp) Main façade

Main façade The pediment, with the central figures of the Nation and Liberty: statesmen and scholars to the left, soldiers to the right

The pediment, with the central figures of the Nation and Liberty: statesmen and scholars to the left, soldiers to the right

The façade and peristyle on the east side, modeled after a Greek temple, features Corinthian columns and pedimental sculpture by David d'Angers, completed in 1837. The sculpture on this pediment, replacing an early pediment with religious themes, represents "The Nation distributing crowns handed to her by Liberty to great men, civil and military, while history inscribes their names". To the left are figures of distinguished scientists, philosophers, and statesmen, including Rousseau, Voltaire, Lafayette, and Bichat. To the right is Napoleon Bonaparte, along with soldiers from each military service and students in uniform from the École Polytechnique.[19] Below is the inscription: "To the great men, from a grateful nation" ("Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaissante"). This was added in 1791, when the Panthéon was created. It was removed during the Restoration of the monarchy, then put back in 1830.

The richly detailed Corinthian order

The richly detailed Corinthian order Bas-reliefs below the peristyle

Bas-reliefs below the peristyle

Below the peristyle are five sculpted bas-reliefs; the two reliefs over the main doors, commissioned during the Revolution, represent the two main purposes of the building: "Public Education" (left) and "Patriotic Devotion" (right).

The façade originally had large windows, but they were replaced when the church became a mausoleum, to make the interior darker and more somber.

Narthex and naves

Panoramic view of interior

Panoramic view of interior Saint Genevieve as a child in prayer, by Puvis de Chavannes (1876)

Saint Genevieve as a child in prayer, by Puvis de Chavannes (1876) Joan of Arc at Orleans, by Jules Eugène Lenepveu

Joan of Arc at Orleans, by Jules Eugène Lenepveu

The primary decoration of the Western Nave is a series of paintings, beginning in the Narthex, depicting the lives of Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris, and longer series on the life of Saint Genevieve, by Puvis de Chavannes, Alexandre Cabanel, Jules Eugène Lenepveu and other notable history painters of the 19th century. The paintings of the Southern nave and Northern Nave continue this series on the Christian heroes of France, including scenes from the lives of Charlemagne, Clovis, Louis IX of France and Joan of Arc. From 1906 to 1922 the Panthéon was the site of Auguste Rodin's famous sculpture The Thinker.

Foucault pendulum

In 1851, physicist Léon Foucault demonstrated the rotation of the Earth by constructing a 67-metre (220 ft) pendulum beneath the central dome. The original sphere from the pendulum was temporarily displayed at the Panthéon in the 1990s (starting in 1995) during renovations at the Musée des Arts et Métiers. The original pendulum was later returned to the Musée des Arts et Métiers, and a copy is now displayed at the Panthéon.[20] It has been listed since 1920 as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture.[21]

Interment in the crypt

A corridor of the Crypt

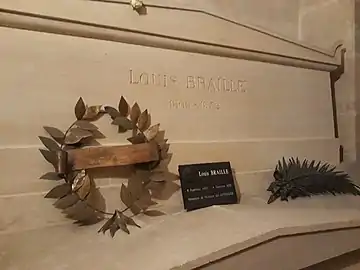

A corridor of the Crypt Tomb of Louis Braille

Tomb of Louis Braille

Interment in the crypt of the Panthéon is severely restricted and is allowed only by a parliamentary act for "National Heroes". Similar high honours exist in Les Invalides for historical military leaders such as Napoléon, Turenne and Vauban.

Among those buried in its necropolis are Voltaire, Rousseau, Victor Hugo, Émile Zola, Jean Moulin, Louis Braille, Jean Jaurès and Soufflot, its architect. In 1907 Marcellin Berthelot was buried with his wife Mme Sophie Berthelot. Marie Curie was interred in 1995, the first woman interred on merit. Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz and Germaine Tillion, heroines of the French resistance, were interred in 2015.[22] Simone Veil was interred in 2018, and her husband Antoine Veil was interred alongside her so that they would not be separated.[23]

The widely repeated story that the remains of Voltaire were stolen by religious fanatics in 1814 and thrown into a garbage heap is false. Such rumours resulted in the coffin being opened in 1897, which confirmed that his remains were still present.[24]

On 30 November 2002, in an elaborate but solemn procession, six Republican Guards carried the coffin of Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870), the author of The Three Musketeers and other famous novels, to the Panthéon. Draped in a blue-velvet cloth inscribed with the Musketeers' motto "Un pour tous, tous pour un" ("One for all, all for one"), the remains had been transported from their original interment site in the Cimetière de Villers-Cotterêts in Aisne, France. In his speech, President Jacques Chirac stated that an injustice was being corrected with the proper honouring of one of France's greatest authors.

In January 2007, President Jacques Chirac unveiled a plaque in the Panthéon to more than 2,600 people recognised as Righteous Among the Nations by the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel for saving the lives of Jews who would otherwise have been deported to concentration camps. The tribute in the Panthéon underlines the fact that around three-quarters of the country's Jewish population survived the war, often thanks to ordinary people who provided help at the risk of their own life. This plaque says:

Sous la chape de haine et de nuit tombée sur la France dans les années d'Occupation, des lumières, par milliers, refusèrent de s'éteindre. Nommés "Justes parmi les nations" ou restés anonymes, des femmes et des hommes, de toutes origines et de toutes conditions, ont sauvé des juifs des persécutions antisémites et des camps d'extermination. Bravant les risques encourus, ils ont incarné l'honneur de la France, ses valeurs de justice, de tolérance et d'humanité. |

Under the cloak of hatred and darkness that spread over France during the years of [Nazi] occupation, thousands of lights refused to be extinguished. Named as "Righteous among the Nations" or remaining anonymous, women and men, of all backgrounds and social classes, saved Jews from anti-Semitic persecution and the extermination camps. Braving the risks involved, they embodied the honour of France, and its values of justice, tolerance and humanity. |

People interred or commemorated

| Year | Name | Lived | Profession | Burial | Picture | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1791 | Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau | 1749–1791 | Revolutionary | — | — | First person honoured with burial in the Panthéon, 4 April 1791. Disinterred on 25 November 1794 and buried in an anonymous grave. His remains are yet to be recovered.[25] |

| 1791 | Voltaire | 1694–1778 | Writer and philosopher | Entrée |  |

|

| 1792 | Nicolas-Joseph Beaurepaire | 1740–1792 | Military officer | — | — | Remains since disappeared |

| 1793 | Louis Michel le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau | 1760–1793 | Politician | — | — | Assassinated deputy; disinterred from the Panthéon at the request of his family on 14 February 1795. |

| 1793 | Auguste Marie Henri Picot de Dampierre | 1756–1793 | Military officer | — | — | Remains since disappeared |

| 1794 | Jean-Paul Marat | 1743–1793 | Politician | — | — | Disinterred from the Panthéon. |

| 1794 | Jean-Jacques Rousseau | 1712–1778 | Writer and Philosopher | Entrée | .jpg.webp) |

|

| 1806 | François Denis Tronchet | 1726–1806 | Politician and lawyer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1806 | Claude-Louis Petiet | 1749–1806 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1807 | Jean-Étienne-Marie Portalis | 1746–1807 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1807 | Louis-Pierre-Pantaléon Resnier | 1759–1807 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1807 | Louis-Joseph-Charles-Amable d'Albert, duc de Luynes | 1748—1807 | Politician | — | — | Disinterred from the Panthéon in 1862 and returned to his family at their request. |

| 1807 | Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Bevière | 1723–1807 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | François Barthélemy, comte Beguinot | 1747–1808 | Military officer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis | 1757–1808 | Scientist and philosopher | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Gabriel-Louis, marquis de Caulaincourt | 1741–1808 | Military officer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Jean-Frédéric Perregaux | 1744–1808 | Banker | Crypt IV | ||

| 1808 | Antoine-César de Choiseul, duc de Praslin | 1756–1808 | Military officer and politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Jean-Pierre Firmin Malher | 1761–1808 | Military officer | Crypt V |  |

Urn with his heart. |

| 1809 | Jean Baptiste Papin, comte de Saint-Christau | 1756–1809 | Politician and lawyer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1809 | Joseph-Marie Vien | 1716–1809 | Painter | Crypt III | ||

| 1809 | Pierre Garnier de Laboissière | 1755–1809 | Military officer | Crypt III | ||

| 1809 | Jean Pierre, comte Sers | 1746–1809 | Politician | Crypt III | Urn with his heart. | |

| 1809 | Jérôme-Louis-François-Joseph, comte de Durazzo | 1739–1809 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

Urn with his heart. |

| 1809 | Justin Bonaventure Morard de Galles | 1761–1809 | Military officer | Crypt III | Urn with his heart. | |

| 1809 | Emmanuel Crétet de Champmol | 1747–1809 | Politician | Crypt III | ||

| 1810 | Cardinal Giovanni Battista Caprara | 1733–1810 | Clergyman | Crypt III | Heart buried in Milan Cathedral in 1810. Body disinterred from the Panthéon in 1861 and returned to his family at their request. His remains were transferred from Paris to Rome on 22 August 1861. | |

| 1810 | Louis Charles Vincent Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire | 1766–1809 | Military officer | Crypt III | ||

| 1810 | Jean-Baptiste Treilhard | 1742–1810 | Lawyer | Crypt III | ||

| 1810 | Jean Lannes de Montebello | 1769–1809 | Military officer | Crypt XXII |  |

|

| 1810 | Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu | 1738–1810 | Politician | Crypt III | ||

| 1811 | Louis Antoine de Bougainville | 1729–1811 | Navigator | Crypt III |  |

|

| 1811 | Cardinal Charles Erskine de Kellie | 1739–1811 | Clergyman | Crypt III | ||

| 1811 | Alexandre-Antoine Hureau de Sénarmont | 1769–1811 | Military officer | Crypt II | Urn with his heart. | |

| 1811 | Cardinal Ippolito Antonio, cardinal Vincenti Mareri | 1738–1811 | Clergyman | Crypt III | .jpg.webp) |

|

| 1811 | Nicolas Marie Songis des Courbons | 1761–1811 | Military officer | Crypt III | ||

| 1811 | Michel Ordener, 1st Count Ordener[26] | 1755–1811 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1812 | Jean Marie Pierre Dorsenne | 1773–1812 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1812 | Jan Willem de Winter | 1761–1812 | Military officer | Crypt IV | Heart buried in Kampen, Overijssel, Netherlands, his birthplace. | |

| 1813 | Hyacinthe-Hugues-Timoléon de Cossé, Comte de Brissac | 1746–1813 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1813 | Jean-Ignace Jacqueminot, Comte de Ham | 1758–1813 | Lawyer | Crypt II | ||

| 1813 | Joseph-Louis Lagrange | 1736–1813 | Mathematician | Crypt II |  |

|

| 1813 | Jean Rousseau | 1738–1813 | Politician | Crypt II | ||

| 1813 | Justin de Viry | 1737–1813 | Politician | Crypt II | ||

| 1814 | Frédéric Henri Walther | 1761–1813 | Military officer | Crypt IV | ||

| 1814 | Jean-Nicolas Démeunier | 1751–1814 | Politician | Crypt II | ||

| 1814 | Jean-Louis-Ébénézer Reynier | 1771–1814 | Military officer | Crypt IV | ||

| 1814 | Claude Ambroise Régnier de Massa di Carrara | 1746–1814 | Politician and lawyer | Crypt II | ||

| 1815 | Antoine-Jean-Marie Thévenard | 1733–1815 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1815 | Claude-Juste-Alexandre Legrand | 1762–1815 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1829 | Jacques-Germain Soufflot | 1713–1780 | Architect of the Pantheon | Entrée |  |

|

| 1885 | Victor Hugo | 1802–1885 | Writer | Crypt XXIV |  |

|

| 1889 | Lazare Carnot | 1753–1823 | Politician and scientist | Crypt XXIII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon at the centennial of the French Revolution. |

| 1889 | Jean-Baptiste Baudin | 1811–1851 | Politician and doctor | Crypt XXIII | Transferred to the Panthéon at the centennial of the French Revolution. | |

| 1889 | Théophile Corret de la Tour d'Auvergne | 1743–1800 | Military officer | Crypt XXIII | Transferred to the Panthéon at the centennial of the French Revolution. | |

| 1889 | François Séverin Marceau | 1769–1796 | Military officer | Crypt XXIII |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Koblenz, Germany, at the centennial of the French Revolution. |

| 1894 | Marie François Sadi Carnot | 1837–1894 | President of France | Crypt XXIII | Buried in the Panthéon immediately after his assassination. | |

| 1907 | Marcellin Berthelot | 1827–1907 | Scientist | Crypt XXV |  |

Buried with his wife Sophie Berthelot as he refused to be buried apart from her.[27] |

| 1907 | Sophie Berthelot | 1837–1907 | Wife of Marcellin Berthelot | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon with her husband Marcellin Berthelot, who had refused to be buried apart from her. The first woman to be interred in the Panthéon. |

| 1908 | Émile Zola | 1840–1902 | Writer | Crypt XXIV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon from Montmartre Cemetery. |

| 1920 | Léon Gambetta | 1838–1882 | Politician | Escalier d'accès |  |

Urn with his heart. |

| 1924 | Jean Jaurès | 1859–1914 | Politician | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon ten years after his assassination |

| 1933 | Paul Painlevé | 1863–1933 | Mathematician and politician | Crypt XXV |  |

|

| 1948 | Paul Langevin | 1872–1946 | Scientist | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Jean Perrin. |

| 1948 | Jean Perrin Nobel Laureate |

1870–1942 | Scientist | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Paul Langevin. Repatriated from New York City, US. |

| 1949 | Victor Schœlcher | 1804–1893 | Abolitionist | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Félix Éboué. Transferred from Père Lachaise Cemetery. Victor Schœlcher had wanted to be buried with his father Marc, who was therefore also interred in the Panthéon. |

| 1949 | Marc Schœlcher | 1766–1832 | Father of Victor Schœlcher | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Victor Schœlcher. Transferred from Père Lachaise Cemetery. Victor had wanted to be buried with his father who was therefore is also interred in the Panthéon. |

| 1949 | Félix Éboué | 1884–1944 | Politician | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Victor Schœlcher. |

| 1952 | Louis Braille | 1809–1852 | Educator | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon on the centenary of his death. |

| 1964 | Jean Moulin | 1899–1943 | Résistant | Crypt VI |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Père Lachaise Cemetery on 19 December 1964. |

| 1967 | Antoine de Saint-Exupéry | 1900–1944 | Writer | — | _Antoine_de_Saint-Exup%C3%A9ry.jpg.webp) |

Commemorated with an inscription in November 1967, as his body was never found following an aerial dog fight over the Mediterranean near Marseille. |

| 1987 | René Cassin Nobel Laureate |

1887–1976 | Human rights activist | Crypt VI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon on the centenary of his birth. Transferred from Montparnasse Cemetery. |

| 1988 | Jean Monnet | 1888–1979 | Economist | Crypt VI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon on the centenary of his birth. |

| 1989 | Abbé Henri Grégoire | 1750–1831 | Clergyman | Crypt VII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon at the bicentennial of the French Revolution. |

| 1989 | Gaspard Monge | 1746–1818 | Mathematician | Crypt VII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon at the bicentennial of the French Revolution. |

| 1989 | Nicolas de Condorcet | 1743–1794 | Politician | Crypt VII |  |

Symbolic interment at the bicentennial of the French Revolution. His coffin at the Panthéon empty, his remains having been lost. |

| 1995 | Pierre Curie Nobel Laureate (1903) |

1859–1906 | Scientist | Crypt VIII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon in April 1995 with his wife and fellow physicist Marie Curie. |

| 1995 | Marie Skłodowska Curie Nobel Laureate (1903 and 1911) |

1867–1934 | Scientist | Crypt VIII |  |

Second woman to be buried in the Panthéon, but the first to be honoured on her own merit. |

| 1996 | André Malraux | 1901–1976 | Writer and politician | Crypt VI |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Verrières-le-Buisson (Essonne) Cemetery on 23 November 1996 on the 20th anniversary of his death. |

| 1998 | Toussaint Louverture | 1743–1803 | Military officer | — | Commemorative plaque installed on same day as that for Louis Delgrès. | |

| 1998 | Louis Delgrès | 1766–1802 | Politician | — | Commemorative plaque installed on same day as that for Toussaint Louverture. | |

| 2002 | Alexandre Dumas | 1802–1870 | Writer | Crypt XXIV | .jpg.webp) |

Transferred to the Panthéon 132 years after his death. |

| 2011 | Aimé Césaire | 1913–2008 | Writer and politician | — |  |

Commemorative plaque installed 6 April 2011; Césaire is buried in Martinique.[28] |

| 2015 | Jean Zay | 1904–1944 | Politician | Crypt IX |  |

Murdered at Molles in Allier and previously buried in Orléans in 1948. |

| 2015 | Pierre Brossolette | 1903–1944 | Résistant | Crypt IX |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Père Lachaise Cemetery on 27 May 2015. |

| 2015 | Germaine Tillion | 1907–2008 | Résistante | Crypt IX |  |

Symbolic interment. The coffin of Germaine Tillion at the Panthéon does not contain her remains but soil from her gravesite, because her family did not want the body itself moved.[29] |

| 2015 | Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz | 1920–2002 | Résistante | Crypt IX |  |

Symbolic interment. The coffin of Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz at the Panthéon does not contain her remains but soil from her gravesite, because her family did not want the body itself moved.[29] |

| 2018 | Simone Veil | 1927–2017 | Politician, Holocaust survivor | Crypt VI |  |

Originally buried at Montparnasse Cemetery following her death in 2017.[30][31] |

| 2018 | Antoine Veil | 1926–2013 | Husband of Simone Veil | Crypt VI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon with his wife Simone Veil. Originally buried at Montparnasse Cemetery following his death in 2013.[30][31] |

| 2020 | Maurice Genevoix | 1890–1980 | Writer | Crypt XIII |  |

Originally buried at Passy Cemetery following his death in 1980. |

| 2021 | Josephine Baker | 1906–1975 | Résistante, entertainer, civil rights activist | Crypt XIII |  |

Symbolic interment. Baker's cenotaph contains soil from her birthplace in Missouri, from France, and from her final resting place in Monaco Cemetery.[17][4][32] |

See also

- Pantheon, Rome

- Panteón Nacional, Caracas

- Pantheon, Moscow

- Church of Santa Engrácia, Lisbon

- The Apotheosis of Washington – dome fresco of the US Capitol

- Listing of the work of Jean Antoine Injalbert-French sculptor Sculptor of statue of Mirabeau.

- History of early modern period domes

- List of tallest domes

References

- "Pantheon definitions". definitions.net. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- Conlin, Jonathan (2013). Tales of Two Cities: Paris, London and the Birth of the Modern City. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1782390190.

- Eisenman, Stephen; Crow, Thomas E. (2007). Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History. Thames & Hudson. p. 163. ISBN 978-0500286500.

- "Josephine Baker to become first Black woman to enter France's Pantheon". The Guardian. August 22, 2021.

Of the 80 figures in the Panthéon, only five are women

- Lebeurre 2000, p. 3

- Patroness of Paris: Rituals of Devotion in Early Modern France. Brill. 1998. ISBN 9004108513.

- Oudin 1994, p. 479

- Lebeurre 2000, p. 9

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 9–10

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 12–13

- Lebeurre 2000, p. 16

- Lebeurre 2000, p. 17

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 26–27

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 26–29

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 33–35

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 58–59

- "Black artist Josephine Baker honored at France's Pantheon". AP News. November 30, 2021.

- Lebeurre 2000, p. 56

- Lebeurre 2000, pp. 43–45

- "Foucault's Pendulum: Interesting Thing of the Day". Itotd.com. 2004-11-08. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- Base Mérimée: PA00088420, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French) Ancienne église Sainte-Geneviève, devenue Le Panthéon

- Angelique Chrisafis (1970-01-01). "France president Francois Hollande adds resistance heroines to Panthéon | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- Willsher, Kim (2018-06-30). "France pays tribute to Simone Veil with hero's burial in the Panthéon". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- Voltaire (1976). Candide. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1105311604.

- Doyle, William (2002). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. UK: Oxford University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0199252985.

- Mullié, Charles (1852). "Michel Ordener". Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 à 1850 (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zaretsky, Robert (October 25, 2013). "Opinion | Why So Few Women in the Panthéon?". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- France Guide (2011). "Aimé Césaire joins Voltaire and Rousseau at the Panthéon in Paris". French Government Tourist Office. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- "Paris celebrates WWII resistance heroes in Pantheon ceremony". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2017-01-15 – via Yahoo News.

- Roe, David (2017-07-05). "France buries women's rights icon Simone Veil". en.rfi.fr.

- Katz, Brigit. "France's Simone Veil Will Become the Fifth Woman Buried in the Panthéon". Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- "Joséphine Baker au Panthéon : retrouvez l'intégralité de la cérémonie" [Joséphine Baker at the Pantheon: transcript of the entire ceremony]. Le Monde (in French). November 30, 2021.

Sources

- Lebeurre, Alexia (2000). The Pantheon: Temple of the Nation. Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine. ISBN 978-2858223435.

- Oudin, Bernard (1994). Dictionnaire des Architectes (in French). Seghers. ISBN 2232103986.

External links

- Panthéon at Centre des Monuments Nationaux

- Panthéon – current photographs and of the years 1900

- Panthéon ou église Sainte-Geneviève? Les ambiguïtés d'un monument, Denis Bocquet, MA Thesis, Sorbonne University 1992

- Panthéon at Structurae