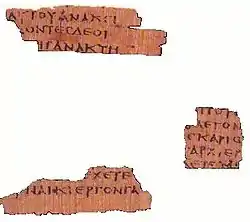

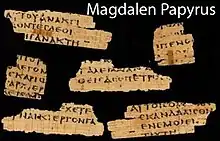

Magdalen papyrus

The "Magdalen" papyrus (/ˈmɔːdlɪn/, MAWD-lin)[1] was purchased in Luxor, Egypt in 1901 by Reverend Charles Bousfield Huleatt (1863–1908), who identified the Greek fragments as portions of the Gospel of Matthew (Chapter 26:23 and 31) and presented them to Magdalen College, Oxford, where they are catalogued as P. Magdalen Greek 17 (Gregory-Aland 𝔓64) from which they acquired their name. When the fragments were published by Colin Henderson Roberts in 1953, illustrated with a photograph, the hand was characterized as "an early predecessor of the so-called 'Biblical Uncial'" which began to emerge towards the end of the 2nd century. The uncial style is epitomised by the later biblical Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus. Comparative paleographical analysis has remained the methodological key for dating the manuscript, but there is no consensus on the dating of the papyrus. Estimates have ranged from the 1st century to the 4th century AD.

| New Testament manuscript | |

| |

| Sign | 𝔓64 |

|---|---|

| Text | Matthew 26:23,31 |

| Date | Late 2nd/3rd century |

| Script | Greek |

| Found | Coptos, Egypt |

| Now at | Barcelona, Fundación Sant Lluc Evangelista, Inv. Nr. 1; Oxford, Magdalen College, Gr. 18 |

| Type | Alexandrian text-type |

| Category | I |

The fragments are written on both sides, indicating they came from a codex rather than a scroll. More fragments, published in 1956 by Ramon Roca-Puig, cataloged as P. Barc. Inv. 1 (Gregory-Aland 𝔓67), were determined by Roca-Puig and Roberts to come from the same codex as the Magdalen fragments, a view which has remained the scholarly consensus.

Date

𝔓64 was originally given a 3rd-century date by Charles Huleatt, who donated the Manuscript to Magdalen College. Papyrologist A. S. Hunt then studied the manuscript and dated it to the early 4th century. After initially preferring a 3rd or possibly 4th century dating for the papyrus, Colin Roberts published the manuscript and gave it a dating of c. 200, which was confirmed by three other leading papyrologists: Harold Bell, T. C. Skeat and E. G. Turner.[2] In late 1994, Carsten Peter Thiede proposed redating the Magdalen papyrus to the middle of the 1st century (AD 37 to 70). This attracted considerable publicity, as journalists interpreted the claim optimistically. Thiede's official article appeared in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik in 1995. A version edited for the layman was co-written with Matthew d'Ancona and presented as The Jesus Papyrus, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1996. (also published as: Eyewitness to Jesus, 1996, New York: Doubleday). Thiede's redating of the papyrus was based on comparative analysis of the script with selected samples from Egypt and Palestine. He claimed to see similarities between the script of the Magdalen papyrus and that of dated documents from the 1st century CE, such as P.Oxy. II 246 (66 CE). Thiede's hypothesis has been viewed with scepticism by nearly all established papyrologists and biblical scholars.[3]

Philip Comfort and David Barret in their book Text of the Earliest NT Greek Manuscripts argue for a more general date of 150–175 for the manuscript, and also for 𝔓4 and 𝔓67, which they argue came from the same codex. 𝔓4 was used as stuffing for the binding of “a codex of Philo, written in the later 3rd century and found in a jar which had been walled up in a house at Coptos [in 250].”[4] If 𝔓4 was part of this codex, then the codex may have been written roughly 100 years prior or earlier.[5] Comfort and Barret also show that this 𝔓4/64/67 has affinities with a number of the late 2nd-century papyri.[6]

Comfort and Barret "tend to claim an earlier date for many manuscripts included in their volume than might be allowed by other palaeographers."[7] The Novum Testamentum Graece, a standard reference for the Greek witnesses, lists 𝔓4 and 𝔓64/67 separately, giving the former a date of the 3rd century, while the latter is assigned c. 200.[8] Charlesworth has concluded 'that 𝔓64+67 and 𝔓4, though written by the same scribe, are not from the same ... codex.'[9] The most recent and thorough palaeographic assessment of the papyrus concluded that "until further evidence is forthcoming perhaps a date from mid-II to mid-IV should be assigned to the codex."[10]

See also

Notes

- "Magdalen (Name)". First Names Dictionary on AskOxford.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- Colin Roberts, An Early Papyrus pp. 233–237; Nongbri, God's Library 265-267

- See Head, Peter M. "The Date of the Magdalen Papyrus of Matthew (P. Magd. Gr. 17 = P64): A Response to C. P. Thiede" Archived 2010-11-25 at the Wayback Machine, (1995) Tyndale Bulletin 46. Retrieved on 25 October 2013

- Colin Roberts, Manuscript, Society, and Belief in Early Christian Egypt pp. 8

- Philip Wesley Comfort and David P. Barrett, The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts (Wheaton, Ill.: Tyndale House, 2001), pp. 50–53

- i.e. P. Oxy. 224, 661, 2334, 2404 2750, P. Ryl. 16, 547, and P. Vindob G 29784

- Robinson, Maurice A. Review "Philip W. Comfort and David P. Barrett, eds. The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts" (2001) TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism v. 8

- Nestle-Aland. Novum Testamentum Graece (1997). Barbara and Kurt Aland, eds. NA27 Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. 684, 687

- Charlesworth, "P64+67 and P4," 604

- Barker, "The Dating of New Testament Papyri," 578

References

- Barker, Don. "The Dating of New Testament Papyri." New Testament Studies 57 (2011), 571–582, doi:10.1017/S0028688511000129

- Charlesworth, S. D. "T. C. Skeat, P64+67 and P4, and the Problem of Fibre Orientation in Codicological Reconstruction," New Testament Studies 53, 582–604, doi:10.1017/S002868850700029X

- Nongbri, Brent. God's Library: The Archaeology of the Earliest Christian Manuscripts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

- Skeat, T. C. "The Oldest Manuscript Of The Four Gospels?" New Testament Studies 43 (1997), 1–34, doi:10.1017/S0028688500022475

- Thiede, Carsten Peter (1995). "Papyrus Magdalen Greek 17 (Gregory–Aland P64). A Reappraisal" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 105: 13–20. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

Images

- "Liste Handschriften". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- "The Magdalen Papryus: possibly the earliest known fragments of the New Testament". Oxford: Magdalen College. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

External links

- Peter M. Head, "The date of the Magdalen Papyrus of Matthew: A Response to C. P. Thiede": published in Tyndale Bulletin 46 (1995) pp. 251–285; the article suggests that he has both overestimated the amount of stylistic similarity between P64 and several Palestinian Greek manuscripts and underestimated the strength of the scholarly consensus of a date around AD 200.

- University of Münster, New Testament Transcripts Prototype. Select P64/67 from 'manuscript descriptions' box

- T. C. Skeat, The Oldest Manuscript of the Four Gospels?, in: T. C. Skeat and J. K. Elliott, The Collected Biblical Writings of T. C. Skeat, Brill 2004, pp. 158–179.

- "Liste Handschriften". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- "The Magdalen Papryus: possibly the earliest known fragments of the New Testament". Oxford: Magdalen College. Retrieved 10 November 2014.