Papyrus Rylands 458

Papyrus Rylands 458 (TM 62298; LDAB 3459) is a manuscript of the Pentateuch (first five books of the Bible) in the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible. It is a roll made from papyrus, which has survived in a very fragmentary condition. It is designated by the number 957 on the list of Septuagint manuscripts according to the numbering system devised by biblical scholar Alfred Rahlfs. Using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), the manuscript has been dated to the middle of the 2nd century BCE.[1]

Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, it was the oldest known manuscript of the Greek Bible. It has been invariably used in discussions around whether the Greek Septuagint translation used either the Tetragrammaton (name of God) in Hebrew, or the Greek title Κύριος (kyrios/lord).

Description

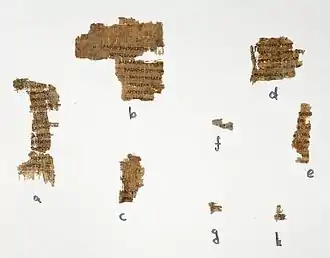

The text was written on papyrus in uncial letters. The manuscript consists of only 8 small fragments, designated by the letters "a"–"h". Fragment "h" is the smallest and contains only two letters. The words are not divided by spaces, but written continuously. The writer uses the colorimetric system, regularly leaving a space at the end of sentence or clause.[2] The surviving text is from the Book of Deuteronomy, namely Deut 23:24(26)–24:3; 25:1–3; 26:12; 26:17–19; 28:31–33; 27:15; 28:2.[2]

The text of the manuscript agrees more with Washington Manuscript I (WI) or Codex Alexandrinus (A) than with Codex Vaticanus (B).[3]

Tetragrammaton

In fragment d which contains part of the text of Deut 26:18, scholars have debated, because instead of the name YHWH or the title Κύριος, it is found in empty space, where the Hebrew text contains the tetragrammaton for the name of God.[4]

Françoise Dunand claimed in 1966: "no doubt in P. Rylands 458 of Deuteronomy the tetragrammaton was written either in square Hebrew as in Papyrus F. 266, or in archaic characters".[5]

Martin Rösel wrote in 2007 that the fragmentary manuscript contains neither Κύριος nor the Tetragrammaton, but it has "a gap in Deut. 26.18 where one would expect either κύριος or the tetragrammaton. This gap is large enough to accommodate both words, and it seems likely that the scribe of the Greek text left the space free for someone else to insert the Hebrew characters of the tetragrammaton."[6] In his view, "from the very beginnings of the translation of the Pentateuch, the translators were using κύριος as an/the equivalent for the Hebrew name of God".[7]

Anthony Meyer in 2017 rejects Rösel's supposition that the Tetragrammaton was likely intended to be inserted into Rylands 458. He cites the directly opposite supposition of C. H. Roberts, who in 1936 wrote: "It is probable that κυριος was written in full, i.e. that the scribe did not employ the theological contractions almost universal in later MSS." However, Paul E. Kahle said in 1957 that Roberts had by then changed his mind and had accepted Kahle's view that "this space actually contained the Tetragrammaton". Meyer objects: There is no measurable gap, waiting to be filled. Instead, the fragment simply breaks off at this point, and Rylands 458 offers no support for the idea that it used the Tetragrammaton at this point.[8]

In 1984 Albert Pietersma also says that the evidence from this manuscript has been overemphasized, "not because it is relevant to our discussion, but because it has been forcibly introduced into the discussion, in part, one surmises, because it is the oldest extant LXX MSS".[9]: 91 He adds with some irony, "One hopes that this text will henceforth be banned from further discussion regarding the tetragram, since it has nothing to say about it".[9]: 92

History of the scroll

Due to its very early assigned date to the mid-2nd century BCE, it is currently one of the oldest known manuscripts of the Septuagint. It is believed it came from the Fayyum (in Egypt), where there were two Jewish synagogues.[2]

The manuscript was discovered in 1917 by biblical scholar J. Rendel Harris. It was examined by A. Vaccari (1936) and biblical scholar Albert Pietersma (1985).[2] The text was edited by papyrologist C. H. Roberts in 1936.[10][11]

The manuscript is currently housed at the John Rylands Library (Gr. P. 458) in Manchester,[2] giving the manuscript its name.

See also

References

- George Howard (1971). "The oldest Greek text of Deuteronomy". Hebrew Union College Annual. Jewish Institute of Religion: Hebrew Union College Press. 42: 125–131. JSTOR 23506719.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1988). Der Text des Alten Testaments. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. p. 190. ISBN 9783438060488.

- "Bible manuscripts", Rylands Papyri, UK: Katapi.

- Meyer 2017, pp. 208.

-

- Dunand, Françoise (1966). "Papyrus grecs bibliques (Papyrus F. inv. 266): volumina de la Genèse et du Deutéronome". JSCS. Publications de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire.; Recherches d'archéologie, de philologie et d'histoire, t. 27. (in French). Le Carie: Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. 45. OCLC 16771829.

- Rösel, Martin (2018). Tradition and Innovation: English and German Studies on the Septuagint. Atlanta: SBL Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-88414-324-6.

- Rösel, Martin (2007). "The Reading and Translation of the Divine Name in the Masoretic Tradition and the Greek Pentateuch". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 31 (4): 411–428. doi:10.1177/0309089207080558.

- Meyer, Anthony (2017). The Divine Name in Early Judaism: Use and Non-Use in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek (Thesis). McMaster University. p. 211. S2CID 165487129.

- Albert Pietersma (1984). "Kyrios or Tetragram: A Renewed Quest for the Original LXX". In Albert Pietersma; Claude Cox (eds.). De Septuaginta. Studies in Honour of John William Wevers on his sixty-fifth birthday (PDF). Mississauga: Benben Publications.

- Roberts, C. H. (1936). Two Biblical Papyri in the John Rylands Library, Manchester. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 25.

- Opitz, H. & Schaeder, H. (2009). Zum Septuaginta-Papyrus Rylands Greek 458. Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der Älteren Kirche, 35(1), pp. 115-117. Retrieved 3 Jul. 2019, from doi:10.1515/zntw.1936.35.1.115

Further reading

- Hans-Georg Opitz, and H. H. Schaeder, Zum Septuaginta-Papyrus Rylands Greek 458, ZNW (1936)

- Frederic G. Kenyon, Our Bible & the Ancient Manuscripts (4th Ed. 1939) Pg 63 & Plate VI.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The text of the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Biblia Hebraica. Wm. Eerdmans. p. 188. ISBN 0802807887.