Paris Belongs to Us

Paris Belongs to Us (French: Paris nous appartient, sometimes translated as Paris Is Ours) is a 1961 French mystery film directed by Jacques Rivette. Set in Paris in 1957 and often referencing Shakespeare's play Pericles, the title is highly ironic because the characters are immigrants or alienated and do not feel that they belong at all.

| Paris Belongs to Us | |

|---|---|

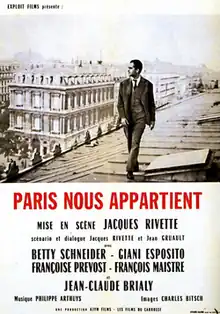

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Jacques Rivette |

| Written by | Jean Gruault Jacques Rivette |

| Produced by | Claude Chabrol Roland Nonin |

| Starring | Betty Schneider Giani Esposito Françoise Prévost |

| Cinematography | Charles L. Bitsch |

| Edited by | Denise de Casabianca |

| Music by | Philippe Arthuys |

Release date |

|

Running time | 141 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

The story centres on an essentially innocent, young university student named Anne who, through her older brother, meets a group of friends haunted by mysterious tensions and fears that lead two of them to commit suicide. Among them is her opposite, a femme fatale named Terry who has had affairs with all the men. The source of the malaise affecting the group is never explained, leaving viewers to wonder how far it might be an amalgam of individual imbalances, general existentialist anxiety, or the paranoia of the Cold War as the world faced the possibility of nuclear annihilation.[1][2][3]

Plot

The film opens with the literature student Anne who is reading Shakespeare when she hears sounds of distress in the next room. There she finds a Spanish girl who says her brother Juan has been killed by dark forces. Anne then meets with her own brother Pierre, who takes her to a party held by some of his friends.

Initially bored and knowing nobody, she gradually becomes fascinated by mysterious interactions around her. Juan, an anti-Franco refugee, has recently died from a knife wound which some think was a suicide. Philip, an unsteady American refugee from McCarthyism, gets drunk and slaps a smartly dressed woman named Terry, accusing her of causing Juan's death by breaking up with him.

The next day, Anne meets with a friend who is an aspiring actor, and he takes her to a rehearsal of Shakespeare's Pericles, the director of which proves to be Gérard, the host of last night's party. Because the actress for the part of Marina has not arrived, Anne is asked to read, and she performs well. Afterward she runs into Philip, who recounts long tales in veiled language about sinister interests that have destroyed Juan and may now get Gérard too.

From there on, Anne becomes determined to resolve the mystery that is obsessing the lives of these people and to save Gérard but in neither project does she succeed because Gérard kills himself, and by the end, she is little wiser. It seems that the threat is not external but in the heads of the survivors.

Cast

- Betty Schneider as Anne Goupil

- François Maistre as Pierre Goupil

- Giani Esposito as Gérard Lenz

- Françoise Prévost as Terry Yordan

- Daniel Crohem as Philip Kaufman

- Jean-Claude Brialy as Jean-Marc

- Jean-Marie Robain as Dr. de Georges

Production

Written in 1957, shot from July to November 1958, but not released until 13 December 1961, it was the film critic Rivette's first full-length film as a director and one of the early works of the French New Wave.[4] Like his fellow Cahiers du cinéma critic Éric Rohmer, Rivette did not find popularity with his early films, and unlike many of the New Wave directors, he remained at Cahiers for most of the core New Wave era from 1958 to 1968, only completing two more full-length films during this time.

As a New Wave characteristic, the film includes cameos for fellow directors Claude Chabrol (who also co-produced the film), Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Demy and Rivette himself.

Reception

The film was met by some London film critics with furious incomprehension however, it was awarded the Sutherland Trophy by the British Film Institute as the most original and innovative film introduced at the National Film Theatre during the year. It had only a brief commercial run in London.[5]

Film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum liked the film: "Jacques Rivette’s troubled and troubling 1960 account of Parisians in the late 50s remains the most intellectually and philosophically mature, and one of the most beautiful...Few films have more effectively captured a period and milieu; Rivette evokes bohemian paranoia and sleepless nights in tiny one-room flats, along with the fragrant, youthful idealism conveyed by the film’s title".[6]

Richard Brody of The New Yorker reviewed the film positively: "Rivette’s tightly wound images turn the ornate architecture of Paris into a labyrinth of intimate entanglements and apocalyptic menace; he evokes the fearsome mysteries beneath the surface of life and the enticing illusions that its masterminds, whether human or divine, create."[7]

The critic Hamish Ford stated: "... for me at least, his debut feature is a perfect film in its way. If the first work of a long career should, at least in the oeuvre-charting rear-vision mirror, offer an appropriately characteristic or even perhaps idiosyncratic entry point into a distinct film-world, then Paris nous appartient is indeed a perfect 'first' Rivette in its combination of formal daring and conceptual elusiveness."[8]

References

- Turner Classic Movies, retrieved 12 February 2018

- Bradshaw, Peter, The Guardian, retrieved 12 February 2018

- The New Yorker, retrieved 12 February 2018

- "Paris Belongs to Us: Nothing Took Place but the Place". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "The B.F.I. Award". Sight & Sound. Vol. 32, no. 1. British Film Institute. Winter 1962–1963. p. 13. Retrieved 3 December 2022 – via Archive.org.

- "Paris Belongs to Us | Jonathan Rosenbaum". www.jonathanrosenbaum.net. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Paris Belongs to Us - The New Yorker". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Paris nous appartient by Hamish Ford at Senses of Cinema

Further reading

- Rivette, Jacques; De Pascale, Goffredo (2003). Jacques Rivette (in Italian). Il Castoro. ISBN 88-8033-256-2.