Punctelia borreri

Punctelia borreri is a species of foliose lichen in the family Parmeliaceae. It is a common and widely distributed species, occurring in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions of Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America. The lichen typically grows on bark of deciduous trees, and less commonly on rock. Some European countries have reported increases in the geographic range or regional frequency of the lichen in recent decades, attributed alternatively to a reduction of atmospheric sulphur dioxide levels or an increase in temperatures resulting from climate change.

| Punctelia borreri | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Lecanoromycetes |

| Order: | Lecanorales |

| Family: | Parmeliaceae |

| Genus: | Punctelia |

| Species: | P. borreri |

| Binomial name | |

| Punctelia borreri | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

The lichen is characterised by a greenish-grey to bluish-grey upper thallus surface, a black lower surface, pseudocyphellae on the surface of the thallus (tiny pores that facilitate gas exchange), and chemically, by the presence of gyrophoric acid in the medulla. There are several lookalike Punctelia species, including P. subrudecta, P. perreticulata, and P. reddenda. These can be distinguished from P. borreri by differences in chemistry, in the nature of the vegetative reproductive structures present on the thallus, or the colour of the thallus underside.

Punctelia borreri is named after William Borrer, a botanist who made the first scientific collections of the lichen in early 19th-century England. James Edward Smith was the first to publish a scientific description of the species in 1807, followed independently a year later by Dawson Turner. It was later assigned as the type species of Punctelia by Hildur Krog when she circumscribed the new genus in 1982. Punctelia borreri is used as a component of traditional Chinese medicine. The lichen has been shown to harbour other organisms, including endophytic fungi and lichenicolous fungi.

Systematics

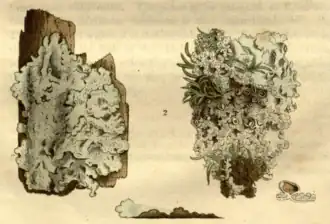

The lichen was first formally described as Lichen borreri by English botanist James Edward Smith in the 25th volume of his work English Botany, published in 1807. The first scientific collections of the lichen were made by another English botanist, William Borrer, whose name is honoured in the species epithet borreri. The type locality was Sussex, where Borrer noted the lichen to be "not uncommon on the trunks of trees, especially on fruit trees". Smith described the specific characteristics of the new species as follows: "Leafy, slightly imbricated, tawny grey, even, sprinkled with white powdery warts; its segments sinuated, rounded at the ends: brown and fibrous beneath. Shields bright chesnut." Smith suggested that it had been overlooked by botanists until that time, who might have mistaken it for the common and widespread Parmelia saxatilis.[2] The type specimen collected by Borrer is now part of the lichen collection at the Natural History Museum in London.[3]

The species had been independently named and described as Parmelia borreri a year earlier in 1806 by Dawson Turner, who, like Smith, had examined specimens sent to him by Borrer. Turner presented his findings to the Linnean Society of London on 3 June 1806, and in a subsequent publication two years later, he gave the lichen a more thorough description in both English and Latin. Turner mentions that he had sent samples to prominent Swedish botanists Erik Acharius and Olof Swartz, "both of whom acknowledged it altogether new to them, and a very distinct species". Similar to Smith's account, Turner's description of the lichen also compares and contrasts it with Parmelia saxatilis; in Turner's opinion, two main characteristics distinguish the two species:

... the thallus of P. borreri is every where even, and destitute of those elevated veins so remarkable and so constant in P. saxatilis; and that the soredia, which in this species are placed upon these veins, as if from their naturally bursting, and which are often confluent to some length, are in P. borreri scatterd [sic] without order over the whole plant, and sometimes in old specimens so numerous as to cover the whole of it except the tips.[4]

Other morphologically similar Parmelia species with point-like pseudocyphellae and simple rhizines were referred to as the Parmelia borreri group, and within the genus Parmelia, they were classified in section Parmelia, subsection Simplices, as defined by Mason Hale and Syo Kurokawa in 1965.[5][6] In 1982, Hildur Krog circumscribed the new genus Punctelia, a segregate of Parmelia. The main characteristics distinguishing the new genus from Parmelia are the development of the pseudocyphellae, the secondary chemistry of the medulla, and phytogeography. Krog transferred twenty-two species to Punctelia from Parmelia. As the earliest-published member of this group, Punctelia borreri was designated the type species of the new genus.[7]

The authorship of this taxon has been in contention, as historically, some have attributed publication of the taxon to Turner. Although Turner was the first to name and describe the species in his 1806 presentation to the Linnean Society, he did not publish his work until 1808, a year after Smith's publication. Smith clearly credits Turner's work, and his text indicates that the lichen he called Lichen borreri was synonymous with Turner's Parmelia borreri.[2] For this reason, the nomenclatural authority Index Fungorum indicates that Parmelia borreri Turner ex Sm. is not a validly published name, according to article 36.1(b) of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.[8] This article states that "A name is not validly published when it is not accepted by its author in the original publication ... when it is merely cited as a synonym".[9] In a 2005 analysis of the taxonomic position of the new lichen species that were collected by Smith and published in English Botany, Jack Laundon proposed to correct the authorship after verifying that Borrer's publication date was indeed before that of Turner, and further noting that it "is now usually known as Punctelia borreri (Sm.) Krog".[3] As of October 2021, Species Fungorum suggests that the correct authorship for this species is Punctelia borreri (Turner) Krog,[1] while MycoBank gives Punctelia borreri (Sm.) Krog.[10]

Synonymy

According to Index Fungorum, the taxon Parmelia pseudoborreri, described by Yasuhiko Asahina in 1951,[11] is synonymous with Punctelia borreri.[12] This is also true of the taxon Parmelia borreri var. pseudoborreri proposed by André Targé and Jacques Lambinon in 1965.[13] Another synonym, Imbricaria borreri,[14] is a result of Gustav Wilhelm Körber's proposed 1846 transfer of the taxon to the genus Imbricaria;[15] this genus name is no longer used for lichens and is considered a synonym of Anaptychia.[16] The taxon Punctelia borreri var. allophyla, published by August von Krempelhuber in 1878,[17] is a synonym of Punctelia borrerina.[18]

In some instances, taxa that were historically proposed as a subspecies or variety of Parmelia borreri have since been elevated to distinct species status. Examples include:

- Parmelia borreri subsp. rudecta (Ach.) Fink (1910)[19] and

- Parmelia borreri var. reddenda (Stirt.) Boistel (1903)[22] = Punctelia reddenda[23]

- Parmelia borreri var. subrudecta (Nyl.) Clauzade & Cl.Roux (1982)[24] = Punctelia subrudecta[25]

- Parmelia borreri var. ulophylla (Ach.) Nyl. (1872)[26] = Punctelia ulophylla[27]

The taxon Parmelia borreri var. coralloidea, proposed by Johannes Müller Argoviensis in 1887,[28] is now known as Pseudocyphellaria glabra.[29]

Phylogenetics

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram showing the phylogeny of Punctelia borreri in genus Punctelia, based on research published in 2016. Letter labels correspond to the five monophyletic clades recognised in Punctelia.[30] |

Molecular phylogenetic analysis has been used to better understand the evolutionary relationships of Punctelia and more accurately determine the limits of species. In the first molecular analysis using genetic material from P. borreri, published in 1998, P. borreri was shown to group together in a clade with P. subrudecta, confirming their genetic relatedness, and demonstrating that the technique could distinguish Punctelia from more distantly related genera like Parmelia and Parmelina.[31] In a 2001 study, the SSU region in the mitochondrial DNA of several species were assessed for their ability to identify evolutionary relationships in the family Parmeliaceae. Limitations in the early applications of this technique were highlighted when the data suggested that P. borreri was more closely related to Melanohalea elegantula than to its congener, Punctelia subflava.[32] The lichen was later (2005) shown to occupy a monophyletic clade with P. perreticulata and P. subpraesignis. Molecular research published in 2016, using a larger sampling of Punctelia species, has revealed that there are five major clades in Punctelia, each clade with characteristic patterns in the chemistry of the medulla. In this analysis, P. borreri is a member of clade E, which contains two species that have fatty acids as their main secondary chemicals. Other members of this clade (and thus most closely related) are P. subpraesignis, P. reddenda, and P. stictica.[30]

Vernacular names

In North America, members of the genus Punctelia are commonly referred to as "speckle shield lichens" or "speckleback lichens", referring to the appearance of the pseudocyphellae.[33] The National General Status Working Group, tasked with establishing a standard set of common names for all wild species in Canada, has proposed the name "Borrer's speckled-back lichen" for Punctelia borreri.[34] Two Chinese common names for the lichen (粉斑星点梅, "pink spotted plum", and 粉斑梅衣, "spotted plum clothes") make reference to its appearance.[35] In Dakota, a Native American language, it was called chan wiziye, meaning "on the side of a tree".[36]

Description

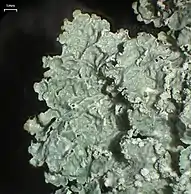

The thallus of Punctelia borreri is foliose (leafy), forming rosettes that are closely attached to their substrate, measuring up to 10 cm (4 in) in diameter.[37] The colour of the upper thallus surface ranges from grey to bluish-grey, greenish-grey,[37] or yellowish-grey. Old herbarium specimens turn buff.[38] Sometimes, the margins of the thallus are whitish from pruina (a powdery coating); at other times they have a brownish tinge.[37] The pruina is often abundant, but not present on all the lobes. In fresh specimens, the pruina gives the lobes a glaucous colour (dull bluish-green).[39] Pruina consists of crystals of calcium oxalate, an insoluble organic calcium salt that is excreted on the thallus surface.[40]

The surface has a smooth and shiny texture, with some wrinkling near the centre of the thallus.[37] Lobes comprising the thallus are flat or concave, measuring 4–8 mm (0.2–0.3 in) wide. Pseudocyphellae are small (up to 300 μm wide), roughly circular, and point-like (punctate); they are more prominent towards the periphery of the thallus. Closer to the centre of the thallus they aggregate in regions with powdery propagules called soralia.[37] The soralia are dot-like, whitish, and distinctly rounded.[41] They arise from pseudocyphellae that are small and punctiform, which often become confluent in age. The soredia are farinose (powdery) to more or less granular on older thalli.[37] Apothecia (sexual propagules) are rarely made by this species; when present, they are lecanorine in form with a width of 2–8 mm (0.08–0.3 in), and with a thalline margin that is often sorediate.[42] Because of the rarity of apothecia, the lichen is thought to reproduce largely asexually through its soredia or soredia-like structures, such as blastidia.[43] These are vegetative propagules containing both mycobiont and photobiont, produced by yeast-like budding.[44]

The lower surface of the thallus is brownish black, typically darkening towards the centre of the thallus.[41] The dark colour is caused by a brown pigment that can be observed in the cortex in thin sections of the thallus.[39] Spier and van Herk have suggested that the colour of the thallus underside gets darker with age, which would explain why the centres of the thalli (the oldest part) are the darkest.[45] There are numerous black or pale brown unbranched rhizines present; these function as holdfasts that attach the thallus to the substrate.[37]

Asci are eight-spored and of the Lecanora-type. The ascospores are broadly ellipsoid in shape, hyaline, and measure 15–18 by 12–15 μm.[37] Pycnidia are apparent as tiny black spots (25–55 μm) immersed in the thallus surface.[39] The pycnoconidia (asexual propagules produced in the pycnidia) are bacilliform to slightly bifusiform (i.e., threadlike with a swelling at both ends), measuring between 4 and 6 μm long and about 1 μm thick.[41] The photobiont partner of Punctelia borreri is chlorococcoid–a spherical, single-celled green algal species.[43]

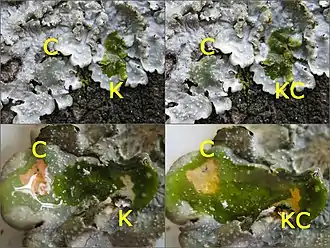

In terms of secondary chemistry, Punctelia borreri is characterised by the presence of gyrophoric acid and unidentified fatty acids in the medulla. The cortex contains atranorin and chloroatranorin.[43] In a study of specimens collected from the Iberian Peninsula, P. borreri also consistently had lecanoric acid, orcynil lecanorate, and orsellinic acid as minor substances. The authors remarked that the presence of lecanoric acid in these samples was surprising.[39] The expected results for standard lichen spot tests are as follows: upper cortex K+ (yellow), C−, KC−, P−; medulla K−, C+ (pinkish-red), KC+ (pinkish-red).[38]

Similar species

The morphology of Punctelia subrudecta is similar to that of P. borreri, in that both lichens have a glossy, non-pruinose outer margin, a mineral grey colour of the lobes, a smooth lobe surface, and mainly laminal soralia. Punctelia borreri, however, has conspicuously white and relatively large pseudocyphellae present over the entire lobe surface, typically has a darker lower surface, and is never covered by smooth secondary lobes. Additionally, Punctelia borreri contains gyrophoric acid rather than lecanoric acid. Punctelia borreri can be distinguished from P. ulophylla by the non-pruinose lobe margin.[46] Punctelia borreri is also similar to P. jeckeri, but contains gyrophoric acid instead of lecanoric acid and the thallus underside is black.[47]

The colour gradient from the periphery to centre of the thallus underside is importance for distinguishing Punctelia borreri from Punctelia subrudecta and Punctelia perreticulata; in these latter two species, the underside is evenly pale throughout, or lighter near the centre.[39] The pseudocyphellae in P. borreri are quite conspicuously white compared to the yellowish pseudocyphellae of P. subrudecta.[45] Also, Punctelia subrudecta reacts C+ red in the medulla, indicating the presence of lecanoric acid as its main secondary chemical.[37] Punctelia reddenda is another member of what has been referred to as the P. borreri group. This species is distinguished by laminal and marginal soralia that have a tendency to form pseudoisidia, and it has a C− medulla.[6] Another lookalike is P. stictica, which can be distinguished from P. borreri by its saxicolous growth, brown margins on the upper thallus surface, and pseudocyphellae that are irregularly shaped.[48]

The subtropical lichen Flavopunctelia borrerioides was named for its resemblance to Punctelia borreri. It features conspicuous rounded laminal pseudocyphellae that develop into soredia, similar to its namesake. Unlike Punctelia, Flavopunctelia species contain usnic acid in the cortex, a secondary chemical that tends to give the thalli of species in this genus a yellowish tinge.[49] Punctelia borrerina was also named for its resemblance to P. borreri. It differs in the chemistry of its medulla, in which its spot test reactions are C− and KC−.[50] Another lookalike is Punctelia transtasmanica, found only in New Zealand and Tasmania. Unlike P. borreri, this Australasian endemic contains lecanoric acid rather than gyrophoric acid as the major secondary chemical in the medulla.[51]

Habitat and distribution

Punctelia borreri usually grows on bark, but is occasionally found growing on rock. The lichen has a cosmopolitan distribution, having been recorded from Africa,[52] Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania,[42] Macaronesia,[6] and South America.[52] Its distribution in North America is largely limited to the west coast from California to Canada. Although some occurrences have been reported in Ohio and West Virginia,[53] it is rare in eastern North America.[54] In Mexico, it only occurs in Veracruz.[48] In Australasia, Punctelia borreri is widely distributed, having been reported throughout eastern Australia and New Zealand. It is fairly common in eastern Australia (including Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria) but is rare in New Zealand.[37] In India it occurs in subtropical and lower temperate regions at altitudes of 1,500–2,200 m (4,900–7,200 ft).[55] A 2017 record from the Hunza Valley in Pakistan was the first documented occurrence for that country.[56]

Before its range expansion in Europe, Punctelia borreri was noted to have a strongly oceanic distribution with scattered occurrences in the central part of the continent.[41] In a 2008 checklist of all parmelioid lichens in Europe (updated in 2011),[57] P. borreri was noted to have been recorded from 21 countries and island groups.[58] In Ireland, the lichen tends to grow on deciduous trees found in well-lit and nutrient-rich areas, such as near farms, by rivers, along hedgerows, and in gardens or orchards.[59] Punctelia borreri is not particularly selective with regards to the type of bark it uses as its substrate. In a Dutch study, it was recorded growing on Norway maple, birch, European hornbeam, European beech, European ash, northern red oak, linden, elm, as well as the genera Robinia and Prunus.[60] Even a plastic light fixture can be a potential substrate for this lichen, provided that it is suitably enriched by eutrophication, such as that which occurs as a result of being a resting spot for birds. When the municipal council of Leusden (Netherlands) decided to replace the plastic lampshades of the streetlights, it was discovered that some of these fixtures, which had been located in an urban tree-rich environment for 25 to 40 years, were covered with lichens, sometimes completely. In one case, P. borreri covered about 80% of the surface of the lampshade, which was remarkable considering that the lichen was not known to exist in the Netherlands until the 1990s.[61]

In the late 1990s, an increase in the frequency of Punctelia borreri was noted in the Netherlands, which, until then, occurred very rarely in the country. This population increase followed a decrease in the levels of the pollutant sulphur dioxide. Flavoparmelia soredians and Flavoparmelia caperata were two other foliose species that experienced a similar increase in regional frequency during this time.[45] Similarly, in the Czech Republic, P. borreri was one of several species of lichens noted to recolonise the lichen-impoverished landscape after the desulfurization of coal power plants in the early 1990s.[62] Changes in the geographical range and regional frequencies of P. borerri have also been attributed to rising temperatures observed in recent decades in central Europe.[63][64] In a 2017 German study determining the suitability of various local lichens as potential bioindicators of climate change, P. borreri was noted to have been very rare in the Rhineland in the 19th century, but increasingly prevalent since 2001.[65] For this reason, it is used as an indicator of climate change in this country.[66] In the Iberian Peninsula, Punctelia borreri had been noted to be a mainly coastal species, but was reported from the central plateau for the first time in 2004 in the Parque del Oeste. This appearance corresponded with the installation of a special fine-mist irrigation system designed to reach a constant relative humidity level in the air, as well as a decrease in sulphur dioxide air pollution in Madrid. These factors caused the resultant environment to be more similar to the climate in coastal regions of the Iberian Peninsula.[67]

Ecology

Several endophytic fungi (fungi that live within the tissue of plants or lichens) have been isolated from the thalli of Punctelia borreri. These include Chaetomium globosum, Hypoxylon fuscum (conidial stage), Nodulisporium hyalosporum,[68] Spirographa ciliata (conidial stage),[69] as well as taxa not identified to species from the genera Chaetomium, Nodulisporium, Phoma, Thielavia, and Scopulariopsis.[68]

Two species of lichenicolous fungi that have been recorded parasitizing Punctelia borreri are Nesolechia oxyspora and Pronectria subimperspicua.[70][71] Infection by the latter of these fungal parasites creates discoloured areas on the host thallus.[72]

Human uses and research

Punctelia borreri has been used in traditional Chinese medicine as an alleged remedy for a variety of ailments, including chronic dermatitis, blurred vision, bleeding from the uterus or from external injuries, and for sores and swelling. To use, a decoction was drunk, or the dried and powdered lichen applied directly to the affected area.[35]

Laboratory tests using the disk diffusion test method have shown that ethanol-based extracts of P. borreri have antimicrobial effects against the bacteria Xanthomonas campestris and Staphylococcus aureus.[73] In a study exploring the potential of several lichens as antidiabetic agents, P. borreri was noted for its in vitro ability to inhibit α-amylase, a key enzyme of carbohydrate digestion.[74][75]

References

- "Synonymy:Punctelia borreri (Turner) Krog". Species Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Smith, James Edward (1807). English Botany. Vol. 25. London: R. Taylor. p. 1780. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Laundon, Jack Rodney (2005). "The publication and typification of Sir James Edward Smith's lichens in English Botany". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 147 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00378.x.

- Turner, Dawson (1808). "Descriptions of eight new British lichens". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 9: 135–150, tab. 13, fig. 2. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1818.tb00332.x.

- Hale, Mason E.; Kurokawa, Syo (1964). "Studies on Parmelia subgenus Parmelia". Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. 36 (4): 121–191.

- Østhagen, Haavard (1974). "The Parmelia borreri group (Lichenes) in Macaronesia" (PDF). Cuadernos de Botánica Canaria. 27: 11–14. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Krog, Hildur (1982). "Punctelia, a new lichen genus in the Parmeliaceae". Nordic Journal of Botany. 2 (3): 287–292. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.1982.tb01191.x.

- "Records details: Parmelia borreri Turner ex Sm., in Smith & Sowerby, Engl. Bot. 25: tab. 1780 (1807)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, 2018 — Shenzhen Code". International Association for Plant Taxonomy.

- "Punctelia borreri (Sm.) Krog, Nordic Journal of Botany 2 (3): 291 (1982) [MB#110966]". MycoBank. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Asahina, Yasuhiko (1951). "Lichenes Japoniae novae vel minus cognitae (5)" [New or less known lichens of Japan (5)] (PDF). Journal of Japanese Botany (in German). 26 (9): 257–261.

- "Records details: Parmelia borreri var. pseudoborreri (Asahina) Targé & Lambinon, Bull. Soc. R. Bot. Belg. 98: 306 (1965)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Records details: Parmelia pseudoborreri Asahina, J. Jap. Bot. 26: 259 (1951)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Records details: Imbricaria borreri (Turner) Körb., Lichenogr. germ. (Breslau): 9 (1846)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Körber, Gustav (1846). Systema Lichenum Germaniae. Die Flechten Deutschlands [The Lichens of Germany] (in German). Breslau: Trewendt & Granier. p. 9.

- "Synonymy: Anaptychia Körb". Species Fungorum. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- Krempelhuber, A. (1878). "Lichenes, collecti in republica Argentina a Doctoribus Lorentz et Hieronymus" [Lichens collected in the Republic of Argentina by Doctors Lorentz and Jerome]. Flora (Regensburg) (in Latin). 61: 433–439, 461–464, 476–480, 492–496, 516–523.

- Canêz, Luciana; Marcelli, Marcelo (2010). "The Punctelia microsticta-group (Parmeliaceae)". The Bryologist. 113 (4): 728–738. doi:10.1639/0007-2745-113.4.728. S2CID 86464397.

- Fink, Bruce (1910). "The lichens of Minnesota". Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. 14 (1): 195. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Tuckerman, Edward (1845). An enumeration of North American Lichenes, with a preliminary view of the structure and general history of these plants, and of the Friesian system; to which is prefixed, an essay on the natural systems of Oken, Fries, and Endlicher. Cambridge: J. Owen. p. 49. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Record Details: Parmelia borreri var. rudecta (Ach.) Tuck., Enum. N. America Lich.: 49 (1845)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Boistel, Alphonse (1903). Nouvelle flore des lichens pour la détermination facile des espèces sans microscope et sans réactifs [New lichen flora for easy species determination without a microscope and reagents] (in French). Vol. 2. Paris. p. 62.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Record Details: Parmelia borreri var. reddenda (Stirt.) Boistel, Nouv. Fl. Lich. 2: 62 (1903)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Roux, C. (1982). "Lichens observés lors de la 8e session extraordinaire de la Société botanique du Centre-Ouest en Provence occidentale" [Lichens observed during the 8th extraordinary session of the Botanical Society of Center-West in Western Province]. Bulletin de la Société Botanique du Centre-Ouest (in French). 13: 210–228.

- "Record Details: Parmelia borreri var. subrudecta (Nyl.) Clauzade & Cl. Roux, in Roux, Bull. Soc. bot. Centre-Ouest, Nouv. sér. 13: 226 (1982)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Nylander, W. (1872). "Observata lichenologica in Pyrenaeis orientalibus". Flora (Regensburg) (in Latin). 55: 545–554. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Record Details: Parmelia borreri var. ulophylla (Ach.) Nyl., Flora, Regensburg 55: 547 (1872)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Müller, J. (1887). "Lichenologische Beiträge XXV". Flora (Regensburg) (in Latin). 70 (4): 56–64. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Record Details: Parmelia borreri var. coralloidea Müll. Arg., Flora, Regensburg 70: 60 (1887)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Alors, David; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten; Divakar, Pradeep K; Leavitt, Steven D.; Crespo, Ana (2016). "An integrative approach for understanding diversity in the Punctelia rudecta species complex (Parmeliaceae, Ascomycota)". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): 1–17. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1146537A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146537. PMC 4749632. PMID 26863231.

- Crespo, Ana; Cubero, Oscar F. (1998). "A molecular approach to the circumscription and evaluation of some genera segregated from Parmelia s. lat". The Lichenologist. 30 (4–5): 369–380. doi:10.1006/lich.1998.0156. S2CID 86448875.

- Crespo, Ana; Blanco, Oscar; Hawksworth, David L. (2001). "The potential of mitochondrial DNA for establishing phylogeny and stabilising generic concepts in the parmelioid lichens". Taxon. 50 (3): 807–819. doi:10.2307/1223708. JSTOR 1223708.

- Brodo, Irwin M.; Sharnoff, Sylvia Duran; Sharnoff, Stephen (2001). Lichens of North America. Yale University Press. pp. 605–606. ISBN 978-0-300-08249-4.

- "Standardized Common Names for Wild Species in Canada". National General Status Working Group. 2020.

- Crawford, Stuart D. (2019). "Lichens used in traditional medicine". In Ranković, Branislav (ed.). Lichen Secondary Metabolites. Bioactive Properties and Pharmaceutical Potential (2 ed.). Springer Nature Switzerland. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-030-16813-1.

- Nowick, Elaine (2014). Historical Common Names of Great Plains Plants, with Scientific Names Index: Volume II: Scientific Names Index. Vol. 2. Zea Books, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-60962-060-8.

- Galloway, D.J.; Elix, J.A. (1983). "The lichen genera Parmelia Ach. and Punctelia Krog, in Australasia". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 21 (4): 397–420. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1983.10428572.

- Nash, T.H.; Ryan, B.D.; Gries, C.; Diederich, P.; Bungartz, F., eds. (2004). Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region. Vol. 2. Tempe: Arizona State University. pp. 435–436. ISBN 978-0-9716759-1-9.

- Longán, A.; Barbero, M.; Gomez-Bolea, A. (2000). "Comparative studies on Punctelia borreri, P. perrireticulata and P. subrudecta (Parmeliaceae, lichenized Ascomycotina)". Mycotaxon. 74 (2): 367–378.

- Giordani, Paolo; Modenesi, Paolo; Tretiach, Mauro (2007). "Determinant factors for the formation of the calcium oxalate minerals, weddellite and whewellite, on the surface of foliose lichens". The Lichenologist. 35 (3): 255–270. doi:10.1016/S0024-2829(03)00028-8. S2CID 86013435.

- Truong, Camille; Clerc, Philippe (2003). "The Parmelia borreri group (lichenized ascomycetes) in Switzerland". Botanica Helvetica. 113 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1007/s00035-003-0674-z (inactive 1 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Elix, John A. (1994). "Punctelia". Lichens—Lecanorales 2, Parmeliaceae (PDF). Flora of Australia. Vol. 55. Canberra: Australian Biological Resources Study/CSIRO Publishing. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-643-05676-3.

- Nimis, P.L. (2016). "Punctelia borreri (Sm.) Krog". ITALIC – The Information System on Italian Lichens. Version 5.0. University of Trieste, Dept. of Biology1. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Ulloa, Miguel; Halin, Richard T. (2012). Illustrated Dictionary of Mycology (2nd ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: The American Phytopathological Society. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-89054-400-6.

- Spier, L.; van Herk, C.M. (1997). "Recent increase of Parmelia borreri in the Netherlands". Lichenologist. 29 (4): 390–393. doi:10.1017/S0024282997000467. S2CID 85659166.

- van Herk, Kok; Aptroot, André (2000). "The sorediate Punctelia species with lecanoric acid in Europe". The Lichenologist. 32 (3): 233–246. doi:10.1006/lich.1999.0261. S2CID 84335673.

- Kukwa, Martin; Motiejūnaitė, Jurga (2012). "Revision of the genera Cetrelia and Punctelia (Lecanorales, Ascomycota) in Lithuania, with implications for their conservation". Herzogia. 25 (1): 5–14. doi:10.13158/heia.25.1.2010.5. S2CID 84596683.

- Egan, RoberT S.; Lendemer, James C. (2016). "Punctelia in Mexico". In Herrera-Campos, Maria; Pérez-Pérez, Rosa Emilia; Nash III, Thomas H. (eds.). Lichens of Mexico. The Parmeliaceae – Keys, distribution and specimen descriptions. Stuttgart: J. Cramer. pp. 453–480. ISBN 978-3-443-58089-6.

- Kurokawa, S. (1999). "Notes on Flavopunctelia and Punctelia (Parmeliaceae)". Bulletin of the Botanic Gardens of Toyama. 4: 25–32.

- Nylander, W. (1896). Les lichens des environs de Paris (in Latin). Paris: Paul. Schmidt. p. 36.

- Elix, John A.; Kantvilas, Gintaras (2005). "A new species of Punctelia (Parmeliaceae, lichenized Ascomycota) from Tasmania and New Zealand". Australasian Lichenology. 57: 12–14.

- Krog, Hildur; Swinscow, T.D.V. (1977). "The Parmelia borreri group in East Africa". Norwegian Journal of Botany. 24 (3): 167–177.

- Aptroot, André (2003). "A new perspective on the sorediate Punctelia (Parmeliaceae) species of North America". The Bryologist. 106 (2): 317–319. doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2003)106[0317:ANPOTS]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85945823.

- McCune, Bruce; Geiser, Linda (1997). Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest (2 ed.). Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-87071-394-1.

- Awasthi, Dharani Dhar (2007). A Compendium of the Macrolichens from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Dehra Dun, India: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh. pp. 411–412. ISBN 978-8121106009.

- Habib, Kamran; Imran, Amna; Khalid, Abdul Nasir; Fiaz, Muhammad (2017). "Some new records of lichens from Hunza Valley, Pakistan" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of Botany. 49 (6): 2475–2482.

- Hawksworth, David L.; Divakar, Pradeep K.; Crespo, Ana; Ahti, Teuvo (2011). "The checklist of parmelioid and similar lichens in Europe and some adjacent territories: Additions and corrections". The Lichenologist. 43 (6): 639–645. doi:10.1017/S0024282911000454. S2CID 86119274.

- Hawksworth, David L.; Blanco, Oscar; Divakar, Pradeep K.; Ahti, Teuvo; Crespo, Ana (2008). "A first checklist of parmelioid and similar lichens in Europe and some adjacent territories, adopting revised generic circumscriptions and with indications of species distributions". The Lichenologist. 40 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1017/S0024282908007329. S2CID 84927575.

- Whelan, Paul (2011). Lichens of Ireland – An illustrated introduction to over 250 species. Cork: Collins Press. pp. 33, 135. ISBN 978-1-84889-137-1.

- van den Boom, Pieter P.G. (2015). "Lichens and lichenicolous fungi from graveyards of the area of Eindhoven (the Netherlands), with the description of two new species" (PDF). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien, Serie B. 117: 245–276.

- van den Bremer, Arie; Spier, Leo (2018). "Een nieuw korstmosbiotoop in Nederland?" (PDF). Buxbaumiella (in Dutch). 112: 1–3.

- Palice, Zdeněk (2017). "Lichen Biota of the Czech Republic". In Danihelka, Jiří; Chytrý, Milan; Pyšek, Petr; Kaplan, Zdeněk (eds.). Flora and Vegetation of the Czech Republic. Germany: Springer International Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 978-3-319-63181-3.

- Shukla, Vertika; Upreti, D.K.; Bajpai, Rajesh (2013). Lichens to Biomonitor the Environment. Dordrecht Springer. p. 120. ISBN 978-8132215035. OCLC 880420585.

- Leuschner, Christoph; Ellenberg, Heinz (2017). Ecology of Central European Forests. Vegetation Ecology of Central Europe. Vol. 1. Springer International Publishing. p. 745. ISBN 978-3-319-43040-9.

- Stapper, N.J.; John, V. (23 May 2017). "Monitoring climate change with lichens as bioindicators". Pollution Atmosphérique, Climat, Santé, Société. 226. doi:10.4267/pollution-atmospherique.4936.

- Möller, Theresa; Oldeland, Jens; Schultz, Matthias (2021). "The value of alien roadside trees for epiphytic lichen species along an urban pollution gradient". Journal of Urban Ecology. 7 (1): juab025. doi:10.1093/jue/juab025.

- Crespo, Ana; Divakar, Pradeep K.; Argüello, Arturo; Gasca, Concepción; Hawksworth, David L. (2004). "Molecular studies on Punctelia species of the Iberian Peninsula, with an emphasis on specimens newly colonizing Madrid". The Lichenologist. 36 (5): 299–308. doi:10.1017/S0024282904014434. S2CID 85777791.

- Li, Wen-Chao; Zhou, Ju; Guo, Shou-Yu; Guo, Liang-Dong (2007). "Endophytic fungi associated with lichens in Baihua mountain of Beijing, China" (PDF). Fungal Diversity. 25: 69–80.

- Punithalingam, Eliyathamby (2003). "Nuclei, micronuclei and appendages in tri- and tetraradiate conidia of Cornutispora and four other coelomycete genera". Mycological Research. 107 (8): 917–948. doi:10.1017/S0953756203008037. PMID 14531616.

- Doré, Caroline J.; Cole, Mariette S.; Hawksworth, David L. (2006). "Preliminary statistical studies of the infraspecific variation in the ascospores of Nesolechia oxyspora growing on different genera of parmelioid lichens". The Lichenologist. 35 (8): 425–434. doi:10.1017/S0024282906005044. S2CID 85036406.

- Joshi, Y.; Upadhyay, S.; Shukla, S.; Nayaka, S; Rawal, R.S. (2015). "New records and an updated checklist of lichenicolous fungi from India". Mycosphere. 6 (2): 195–200. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/6/2/9.

- Zhurbenko, Mikhail P. (2013). "A first list of lichenicolous fungi from India". Mycobiota. 3: 19–34. doi:10.12664/mycobiota.2013.03.03.

- Hamzekhani, Faezeh; Mohammadi, Parisa; Saboora, Azra (2020). "Antimicrobial effects of Leptogium saturninum, Ramalina peruviana and Punctelia borreri". Applied Biology. 33 (2): 33–45. doi:10.22051/JAB.2020.26390.1307.

- Thadhani, Vinitha M.; Karunaratne, Veranja (2017). "Potential of lichen compounds as antidiabetic agents with antioxidative properties: A review". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2017/2079697. PMC 5405387. PMID 28491237.

- Alam, Md. Aftab; Khatoon, Rizwana; Huda, Shamsul; Ahmad, Niyaz; Sharma, Pramod Kumar (2020). "Biotechnological Application of Lichens". In Yusuf, Mohd (ed.). Lichen-Derived Products. Extraction and Applications. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-119-59171-9.

.jpg.webp)