Patrick Burns (businessman)

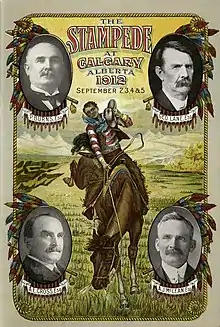

Patrick Burns (July 6, 1856 – February 24, 1937)[1] was a Canadian rancher, meat packer, businessperson, senator, and philanthropist. A self-made man of wealth, he built one of the world's largest integrated meat-packing empires, P. Burns & Co., becoming one of the wealthiest Canadians of his time. He is honoured as one of the Big Four western cattle kings who started the Calgary Stampede in Alberta in 1912.

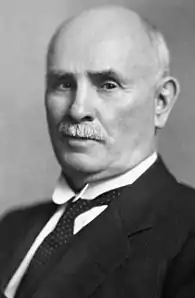

Patrick Burns | |

|---|---|

Pat Burns, 1931. | |

| Canadian Senator from Alberta | |

| In office July 6, 1931 – June 1, 1936 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Patrick O'Byrne July 6, 1856 Oshawa, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | February 24, 1937 (aged 80) Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | Eileen Ellis |

| Parent(s) | Michael and Bridget O'Byrne |

| Occupation | Rancher businessman meat packer |

He made his fortune in the meat industry, but ranching was his true passion. Burns' 700,000 acres (2,800 km2) of cattle ranches covered so vast an area of Southern Alberta that he boasted about being able to travel from Cochrane to the US border without ever leaving his land.[2]

In 1931, he was appointed to the Canadian Senate as a representative for Alberta. On October 16, 2008, the Calgary Herald named Burns as Alberta's Greatest Citizen.[3]

Early life

Patrick O'Byrne was born in Oshawa, Ontario, on July 6, 1856, the fourth of eleven children of Michael and Bridget O'Byrne.[4][5] His parents had immigrated from County Mayo, Ireland in 1848 due to the Great Famine,[6] and as part of the naturalization process, the family name was shortened to Byrne and then later to Burns.[4][7] The family moved from the Oshawa area northward in the spring of 1864 to the small community of Kirkfield, Ontario, where Burns spent a majority of his childhood.[8][9] Patrick had very little formal schooling but learned a great deal about hard work and thriftiness from his parents.[9]

He spent his last summer in Kirkfield chopping wood for a neighbour. He had intended to save enough money to travel out west, but when it came time for him to collect his pay, he discovered that his employer did not have enough cash to cover the $100 he was owed for his labour and so was instead given two oxen as payment. They had a resale value of $70, but he saw an alternative. He made $140 by slaughtering the animals and reselling their meat and byproducts. That experience was one that he would remember when he was as an entrepreneur.

With his brothers John and Dominic in 1878 he head out west at the age of 22. They started out by steamer, but when they reached Rat Portage, he feared that if he paid for transportation the rest of the way, he might lack funds on his arrival. Undaunted, he bought some bread and cheese, and with his gun for protection, walked the rest of the way to Winnipeg. He and John, impressed by reports of good lands to the west, decided to take advantage of the Canadian Dominion Lands Act of 1872. The brothers set out on foot to locate their homesteads and walked 160 miles (260 km) until they found land to their liking just east of Minnedosa, Manitoba.[10]

Burns continued to homestead in Manitoba until after the Louis Riel rebellion but gradually became involved in buying cattle and selling meat. He began his meat packing career with a cow bought on credit and sold for $4.[11] He began freighting goods from Winnipeg and driving his neighbours' cattle to the Winnipeg market. By 1885, he was buying and selling his own cattle.[1]

As a contractor from railway construction, that Burns transitioned from being a small-time broker to a successful entrepreneur. In 1887, William Mackenzie and his partners Donald Mann, James Ross, and Herbert Holt secured a railway construction contract to drive a line from Quebec through Maine to the Eastern Seaboard. Mackenzie had grown up in Kirkfield and remembered Burns from their briefly-shared school days and time spent working in their fields. Aware of Burns' experience in the livestock business, Mackenzie gave him the opportunity to provision the labourers who were to construct the line.

Burns learned to establish a mobile slaughtering facility, which could move easily as the railhead was extended. The success of the contract in Maine led to whole succession of other contracts with Mackenzie and Mann.[12]

Alberta

Burns moved to Calgary in 1890 and established his first substantial slaughterhouse.[13] In 1898, he built a packing house in Calgary followed by others in Vancouver, Edmonton, Prince Albert, and Regina. He then turned to ranching on a large scale and acquired large tracts of land. His company, P. Burns & Co. (later Burns Foods) became western Canada's largest meatpacking company.[13] At the grand opening of his second abattoir in 1899 (the first had burned down), the Calgary Herald described the event as "the passing of yet another milestone on the road to Calgary's full measure of prosperity."[2]

In 1901 he married Eileen Ellis of Penticton in a small ceremony in London, England. Back in Calgary, Burns was building a house for him and his new bride. Burns Manor, on the corner of 4th Street and 13th Avenue SW, designed by Pat's friend, the famed architect Francis Rattenbury, was a grand, 18-room sandstone mansion, visited by the likes of Prime Ministers and Royalty.[14] Construction took two years, and the couple meanwhile lived at the Alberta Hotel, on Stephen Avenue. The Burnses had one son, Patrick Michael Burns, born in Calgary in 1906.

In 1912, he was one of the Big Four, who started the Calgary Stampede. With A.E. Cross, A.J. McLean, and George Lane, they arranged $100,000 worth of financing and billed the event as "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth."[15] Burns then personally owned six ranches with 38,000 head of cattle, 1,500 horses and 20,000 sheep. His company, Burns Foods, had abattoirs in Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, Prince Albert, and Regina with an overall daily capacity of 1,070 cattle, 6,000 pigs, and 3,000 sheep. Burns' facilities were of the utmost sanitation and technically advanced to a level previously unseen in Western Canada. Facilities were eventually opened in Winnipeg, Seattle, Australia, and Great Britain.

Burns was able to revolutionize the slaughterhouse industry by emphasizing efficiency in the use of byproducts.[16] Traditionally, much of the animals had been lost to waste, but with his advanced abattoirs, Burns could expand the list of recoverable products, which included leather, fats for soap, bone for bone meal and manufactured articles, fertilizers, glycerine, hair for brushes, and even an array of pharmaceuticals. Burns joked that the only product not recovered were the pigs' squeals, which could have been sold to politicians.[16]

Burns played a crucial role in World War I by supplying meat to troops overseas.[17] For example, he shipped over 2,000 tons of pork shipped to troops in France during the first half of 1917. After the war, Belgium was looking to secure a meat supply from a North American company. With no American distributors able to meet the call, Burns stepped in to help the devastated nation.

British Columbia

From the early 1900s to 1914, he was the principal meat supplier for the workers during the construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. One of the Foley, Welch and Stewart, sternwheelers, the Skeena was used for the express purpose of delivering Burns' beef to the railway construction camps in British Columbia.[11]

As part of his western expansion, Burns purchased several thousand acres of land south of Vancouver with the intent of using it for grazing cattle.[18] The property included a significant amount of wetland that was not ideal terrain for cattle grazing and so failed. The land was renamed the Burns Bog and maintained its original state until around the 1940s, when peat harvesting began and parts of the bog were dug up.

In 1907, Dominic Burns, a brother, oversaw the construction of Burns Foods' first slaughterhouse in Vancouver.[19] When it was torn down in 1969 the man in charge of the demolition said it was the toughest building to destroy he had ever seen with brick walls that were 36 centimetres (14 in) thick.[19] Burns constructed the historic 18 West Hastings Street as his regional head office and one of several retail outlets in the city. The building is a six-storey brick Edwardian commercial building on West Hastings Street, Vancouver. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Hastings Street corridor was the centre for Vancouver's trade and manufacturing.[20]

In 1910, Dominic had the Vancouver Block built on Granville Street, Vancouver. Dominic moved into the penthouse upon completion of the building in 1912 and lived there until his death in 1933. The building is recognized by its large clock tower and has incredible historic value with its prominent location, the highest point of land in Downtown Vancouver, and being an early example of Edwardian commercial buildings that typified the building boom at the turn of the 20th century.[21]

The Blakeburn coalmine, near Princeton and Coalmont, was another of Burns' ventures.

Bow Valley Ranch

The Bow Valley Farm became the functional headquarters of his cattle empire.[7] Burns purchased the Ranche in 1902 from William Roper Hull.[22] Burns also acquired adjacent sections of land, as they became available. Eventually, the Burns Ranch at Bow Valley included some 20,000 acres (81 km2) bounded on the north by what is now Stampede Park, on the east by the Bow River, on the south by 146th Avenue, and on the west by MacLeod Trail, a large property by any standards but only a small segment of his ranching empire.[22] The farm was an ideal location with respect to the Burns family meat packing plant. Many large cattle drives were brought to the site where the animals were bedded, fed, watered and rested before being herded to the stockyards. Burns frequently offered the hospitality of the ranch to distinguished people visiting the Calgary area.

Hull was responsible for building the natural brick two storey Bow Valley Ranche House which was said to be the finest country home in the territories. When Burns bought the property, the house was a two-hour ride away from Calgary, and he used it as a weekend retreat. Today, the house is occupied by the Bow Valley Ranche Restaurant in Fish Creek Provincial Park.

After his death, his nephew and business successor Michael John Burns came to live in Bow Valley Ranche House.[7] Under his supervision, the ranching operation continued to prosper and he also preserved the established tradition of true western hospitality remembered by many Calgarians. In failing health, Michael John Burns moved to Calgary in 1950, and his son Richard J. Burns came to live at the ranch with his wife and three sons. Under his management, many more improvements were made, including the construction of a tennis court, a swimming pool, and a one-story addition. Richard J. Burns lived at the site until 1970.[7] In 1973, the Alberta Provincial Government purchased the Bow Valley Ranche from the Burns Foundation as part of the development of Fish Creek Provincial Park.[7]

Later years

By the Great War, Burns had become one of Canada's most successful businessmen and had butcher shops and abattoirs all across Western Canada. He had over 100 retail meat shops in the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. He also established 65 creameries and cheese factories, 11 wholesale provision houses and 18 wholesale fruit houses. He extended his empire overseas and set up agencies in London, Liverpool and Yokohama.[7] In 1928, Burns Foods generated sales of about $40 million ($622 million in 2021).[23]

In 1928, he sold his interests in Burns Foods for $15 million ($233 million in 2021) to Dominion Securities and the company was renamed Burns & Co. Ltd.[24][23] In the sale, Burns retained control over his true passion, his vast cattle ranches. At the height of his empire, his assets included nearly 700,000 acres (2,800 km2) of ranch land, roughly the size of Luxembourg.[7] One of his most prized possessions was the Bar U Ranch, south of Calgary, which was among the largest in the country and one of the first and most enduring large corporate ranches of the West. Under George Lane, it had achieved an international repute as a centre of breeding excellence for cattle and purebred Percheron horses. Burns acquired the property from Lane's estate after his close friend died in 1925.[25] Some of the other ranches in his possession were Willow Creek, Glengarry (44), Bradfield, Two Dot, Rio Alto, Linehum, Flying E, and C.K.[7]

In 1931, he was appointed to the Senate of Canada by his close friend, R. B. Bennett, to represent the senatorial division of Northern Alberta. In making the announcement, Prime Minister Bennett had this to say about him: “Holding your wealth as a trust, you have given generously to every good cause and your life has been an inspiration to the younger generation.” He sat as an independent until he resigned for health reasons in 1936.

He was predeceased by both his wife, Eileen, and their son, Patrick Michael. He died in Calgary on February 24, 1937, with his nephew John and other family at his side. He is buried alongside his son in St. Mary's Cemetery in Calgary.

Upon his death, he left his estate to his nieces and nephews and many charities. The tax on his estate was enough to offset the provincial deficit and balance the budget.[26] As a result, the Social Credit Party chose to eliminate the Provincial Sales Tax permanently.

Philanthropy

Burns was known as a man of few words but great generosity. One employee estimated that for a period Burns was donating over $50,000 per year ($778 thousand in 2021).

When a huge rock slide devastated the community of Frank, Alberta in 1903, Burns was among the first to send aid.[9] Five years later, when fire swept through Fernie, British Columbia, leaving 6,000 people homeless, he sent carloads of food.[9] He was a staunch supporter of many children’s charities, making sure that the local orphanage was always well-stocked with free high-quality meat. He was an active Catholic but also supported other religious groups. When he was called upon to pay for the painting of a small Catholic church near Calgary, he requested for the Anglican church next door to be painted as well, at his expense, so that it did not look shabby by comparison. He was extremely generous to the Diocese of Calgary and donated large sums to St. Mary's Parish.[27] He donated three 750 lb bells to St. Mary's Cathedral in 1904 that were cast by the Fonderie Paccard in Anncey, France. The bells were the only parts from the old building used in the construction of the existing cathedral. He paid for the construction of Albert Lacombe's "Hermitage" in Pincher Creek, and donated the land for the Lacombe Nursing Home at Midnapore, which he kept provisioned at his expense.

Burns placed a high value on education. He contributed to the creation of Western Canada College, now Western Canada High School, in Calgary, provided the funding for the erection of St. Joseph's College at the University of Alberta, and financed construction on a new school building, new residence, and donated land for expansion at Vancouver College in Vancouver.[28]

On August 11, 1914, he offered £10,000 to equip a complete "Legion" (Mounted Rifles Regiment) of Canadian Legion of Frontiersmen, for the Canadian Government's war effort.[29]

In 1914, Pope Benedict XV created him a Knight Commander of the Order of St. Gregory the Great, the first Canadian to receive such an honour. He was also a Knight of St. John of Jerusalem, and an honorary colonel in Calgary's 31st Regiment.[27]

In honour of his 75th birthday, a huge cake (said at the time to be the world’s largest birthday cake) led the Stampede parade and was cut and distributed that evening to the city's underprivileged citizens.[9] Also, he celebrated his birthday by giving a 5 lb roast to every family in which the head of the house was unemployed and a ticket for a meal at any restaurant in the city to the unmarried unemployed. It was during the Depression days, and the gifts were much needed; 2000 Calgary families received the roasts and 4000 single unemployed dined out at his expense.

Patrick Burns took special interest to environment conservation.[7] Recognizing the value of the trees in Fish Creek Valley, he directed his foreman to erect fences around the groves of aspen and poplar as protection from the cattle. They also planted 2000 poplars along the MacLeod Trail, adjacent to Bow Valley Ranche.

Burns Memorial Fund

In his will, Burns endowed a third of his estate to the Burns Memorial Fund. As such, in 1939 a court order was issued setting up trusteeship and administration of The Burns Memorial Bequest Fund for three groups of beneficiaries:[9]

- Widows and orphans of members of the police force of Calgary

- Widows and orphans of members of the fire brigade of Calgary

- Poor, indigent and neglected children of Calgary

Today, the Burns Memorial Fund is made up of a private charitable foundation (the Children’s Fund) and two non-profit trusts (the Police Fund and the Fire Fund). The funds operate collectively as the Burns Memorial Fund.

Death and legacy

Burns died February 24, 1937—less than six months after the death of his son.

Estate

After his death, Burns' estate was assessed at $3.8 million ($70 million in 2021)—having fallen significantly due to the Great Depression.[24] In 1996, Maple Leaf Foods purchased a majority of Burns Foods for an undisclosed amount.[30] Some Maple Leaf products retain the Burns name but many have been rebranded.[31]

Alberta's Greatest Citizen

As part of its 125th anniversary, the Calgary Herald organized the search for Our Greatest Albertan. In what is considered the largest citizen journalism project in the province, readers originally nominated 125 people for consideration. A Top 10 list was culminated from months of thought, debate, and votes from the public. Along with Burns, the list included former Premier Peter Lougheed, former Mayor and Lieutenant-Governor Grant MacEwan and Famous Five member Nellie McClung. On October 16, 2008, at a gala at Heritage Park, Burns was named the province's greatest citizen. The Herald commented that "His story is the story of Alberta. His struggles, his dreams, his success and philanthropy define the very core of our western character."[3]

Influence on ranching

Burns was a major force behind the growth of ranching in Alberta. He purchased large herds of purebred Hereford stock, which he used to help fellow ranchers improve the blood lines of their own cattle. A pioneer of cold-weather ranching, Burns put up 250,000 tons of hay for winter feed and convinced other ranchers to utilize winter feeding methods themselves. He renovated the corrals and feeding pens on his ranches and introduced modern feed-lot techniques to finish cattle for market.

Namesakes

Buildings

- Burns Manor, Calgary

- Burns Block, Calgary

- Burns Block, Nelson

- Burns Block, Vancouver

- Burns Building, Calgary[32]

- Burns Stadium (former home of the Calgary Cannons), Calgary,[33]

- Senator Patrick Burns Building at SAIT Polytechnic, Calgary[34]

- Senator Patrick Burns School, Calgary[35]

Land

- Burns Bog, Delta, British Columbia[36][37] (Named after Burns' brother, Dominic)

- Mount Burns, Alberta[15]

Neighbourhoods

Ranches

The following is a list of ranches owned wholly or in part by Patrick Burns or his companies:

- OH/Rio Alto Ranch

- Bar U Ranch

- Bow Valley Ranch

- CK Ranch

- Ricardo Ranch

- Circle Ranch

- Walrond Ranch

- Bradfield Ranch

- Lineham Ranch

- Glengarry Ranch

- Flying E Ranch

- 76 Ranch

- Two Dot Ranch

References

References

- Breen, David H. (May 28, 2008). "Patrick Burns". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- "Patrick Burns: A man of his word Pat burns also used first nations children from Dunbow School in calgary. Dunbow industrial school was made up of children from treaty 6, 7, 8 and of those children the boys were split into two groups. The morning group would do all the haying work for Pat Burn sin the morning while the other group was in class and in the afternoon the groups would switch and the group who was haying for free in the morning would return to class and the other half of the boys would then go to work for free in the fields for Pat Burns. of". Calgary Herald. September 13, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "Best of Alberta. Our Greatest Citizen Announced". Calgary Herald. October 18, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- MacEwan 1979, p. 12.

- Patrick Burns' grave stone indicates his date of birth as July 6, 1956, while the family prayer book kept by his mother Bridget O'Byrne notes his birth as July 6, 1955.

- MacEwan 1979, p. 11.

- "Pioneers: The Burns Era". Bow Valley Ranche. Archived from the original on January 21, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- MacEwan 1979, p. 13.

- "Senator Patrick Burns". Burns Memorial Fund. December 15, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Shiels, Bob (1974). Calgary: a not too solemn look at Calgary's first 100 years. Calgary, Alberta: The Calgary Herald. p. 92. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Downs, Art (1971). Paddlewheels on the Frontier: The Story of B.C. Sternwheel Steamers, Volume 1. Foremost Publishing. pp. 56–57, 72. ISBN 0-88826-033-4.

- Evans, Simon M. (2004). The Bar U & Canadian Ranching History. University of Calgary Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 1-55238-134-X. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- MacLachlan, Ian R. (February 7, 2006). "Meat-Processing Industry". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- Cornerstones: Patrick Burns (Manor House). Calgary Public Library. Accessed April 15, 2008. Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Mount Burns". cdnrockiesdatabases.ca. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- MacEwan 1979, p. 106.

- MacEwan 1979, p. 107.

- "U-Haul SuperGraphics – Burns Bog British Columbia". Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "Chronology 1906–08". The History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "18 West Hastings Street". Canada's Historic Places. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Heritage Revitalization Agreement and Interior Designation for 736 Granville Street 2005-12-06 Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Site History". Bow Valley Ranche. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- Child, Arthur J.E. (October 15, 1970). "Man in Management". Empire club Foundation. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- "Burns, Patrick".

- Parks Canada – Bar U Ranch National Historic Site of Canada – Natural Wonders & Cultural Treasures Archived October 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- MacEwan 1979, pp. 175–176.

- Juliette Champagne (September 5, 2005). Burns made his mark in business, charity. Western Catholic Reporter. Accessed April 15, 2008. Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Sproule, Albert Frederick (1962). The Role of Patrick Burns in the Development of Western Canada. Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta.

- "Canada Offers". Evening Post. Vol. LXXXVIII, no. 38. Wellington, New Zealand. August 13, 1914. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Duckworth, Barbara (September 19, 1996). "Maple Leaf buys major stake in Burns". The Western Producer.

- "Maple Leaf Foods 2020 Annual Information Form" (PDF).

- Cornerstones:Burns Building. Calgary Public Library. Accessed April 15, 2008. Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Foothill (Burns) Stadium".

- "History of SAIT". SAIT Polytechnic. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "About Our School". Senator Patrick Burns School. Calgary Board of Education. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Burns Bog Archived October 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Burn's Bog". Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "Burnsland Cemetery". City of Calgary. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "Riley Park". City of Calgary. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "'A lot of people have been left out': New Port Coquitlam park naming policy aims to reflect city's diversity". Tri-City News. June 16, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

Works cited

- MacEwan, Grant (1979). Patrick Burns, Cattle King. Saskatoon, Sask.: Western Producer Prairie Books. ISBN 0888330103.

- Sproule, Albert Frederick (1962). The Role of Patrick Burns in the Development of Western Canada. Edmonton, Alta.: University of Alberta. OCLC 1157188195.

External links

- Elofson, Warren (2016). "Burns, Patrick". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XVI (1931–1940) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Patrick Burns: A Man of His Word

- Patrick Burns' Manor House Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Best of Alberta. Our Greatest Citizen Announced

- Patrick Burns – Parliament of Canada biography

- Burns Memorial Fund

- The Ranche Restaurant at the Bow Valley Ranche Archived November 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine