Paul Morphy

Paul Charles Morphy (June 22, 1837 – July 10, 1884) was an American chess player. Living before chess had a formal world championship, he was widely acknowledged to be the greatest chess master of his era. He won the tournament of the First American Chess Congress of 1857, winning matches with each opponent by lopsided margins. Morphy then traveled to England and France to challenge the leading players of Europe. He played formal and informal matches with most of the leading English and French players, and others including Adolf Anderssen of Germany, again winning all matches by large margins. He then returned to the United States, and before long abandoned competitive chess. A chess prodigy, he was called "The Pride and Sorrow of Chess" because he had a brilliant chess career but retired from the game while still young.[1] Commentators agree that Morphy was far ahead of his time as a chess player, though there is disagreement on how his play, and his natural talent, rank compared to modern players.

| Paul Morphy | |

|---|---|

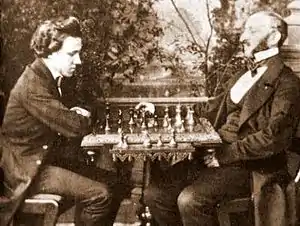

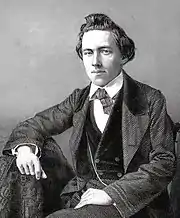

Morphy in Philadelphia, 1859 | |

| Full name | Paul Charles Morphy |

| Country | United States |

| Born | June 22, 1837 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | July 10, 1884 (aged 47) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

Biography

Early life

Morphy was born in New Orleans to a wealthy and distinguished family. His father, Alonzo Michael Morphy, a lawyer, served as a Louisiana state legislator, Attorney General, and a Louisiana State Supreme Court Justice. Alonzo, who held Spanish nationality, was of Spanish and Irish ancestry. Morphy's mother, Louise Thérèse Felicitie Thelcide Le Carpentier, was the musically talented daughter of a prominent French Creole family. Morphy grew up in an atmosphere of genteel civility and culture where chess and music were the typical highlights of a Sunday home gathering.[2]

Sources differ about when and how Morphy learned how to play chess.[3] According to his uncle, Ernest Morphy, no one formally taught Morphy how to play chess; rather, Morphy learned on his own as a young child simply from watching others play. After silently watching a lengthy game between Ernest and Alonzo, which they abandoned as drawn, young Paul surprised them by stating that Ernest should have won.[4] His father and uncle had not realized that Paul knew the moves, let alone any chess strategy. They were even more surprised when Paul proved his claim by resetting the pieces and demonstrating the win his uncle had missed.[4] That anecdote, however, is dismissed as apocryphal by Edge.[5]

In 1845, Ernest acted as the second for Eugène Rousseau in Rousseau's match with Charles H. Stanley, and Paul was taken along.[6]

Childhood victories

By the age of nine, Morphy was considered one of the best players in New Orleans. In 1846, General Winfield Scott visited the city on his way to the Mexican War and let his hosts know that he desired an evening of chess with a strong local player.[7] Chess was an infrequent pastime of Scott's, but he enjoyed the game and considered himself a formidable player. After dinner, the chess pieces were set up and Scott's opponent was brought in: diminutive, nine-year-old Morphy.[7] Scott was at first offended, thinking he was being made fun of, but he consented to play after being assured that his wishes had been scrupulously obeyed and that the boy was a "chess prodigy" who would prove his skill.[7] Morphy easily won both of their two games, the second time announcing a forced checkmate after only six moves.

During 1848 and 1849, Morphy played the leading New Orleans players.[8] Against the strongest of these, Eugène Rousseau, he played at least fifty games, and lost at most five.[9]

In 1850, when Morphy was twelve, the chess master Johann Löwenthal visited New Orleans. Löwenthal, a refugee from the Hungarian revolution of 1848, had visited various American cities, competing successfully with the best local players. He accepted an invitation to Judge Morphy's house to play against Paul.[10]

Löwenthal soon realized he was up against a formidable opponent. Each time Morphy made a good move, Löwenthal's eyebrows shot up in a manner described by Ernest Morphy as "comique".[11] Löwenthal played three games with Paul Morphy during his New Orleans stay, scoring two losses and one draw (or, according to another source, losing all three).[12]

Schooling and the First American Chess Congress

After 1850, Morphy did not play much chess for a long time.[14] Studying diligently, he graduated from Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, in 1854. He then stayed on an extra year, studying mathematics and philosophy. He was awarded an A.M. degree with the highest honors in May 1855.

He studied law at the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University) and received an L.L.B. degree on April 7, 1857. During his studies, Morphy is said to have memorized the complete Louisiana Civil Code.[15]

Not yet of legal age to begin the practice of law, Morphy found himself with free time.[16] He received an invitation to participate in the First American Chess Congress, to be held in New York from October 6 to November 10, 1857. He at first declined, but at the urging of Judge Alexander Beaufort Meek, a close family friend, eventually decided to play.[17] He defeated each of his rivals, including James Thompson, Judge Meek, and two strong German masters, Theodor Lichtenhein and Louis Paulsen, the latter two in the semifinal and final rounds. Morphy was hailed as the chess champion of the United States, but he appeared unaffected by his sudden fame. According to the December 1857 issue of Chess Monthly, "his genial disposition, his unaffected modesty and gentlemanly courtesy have endeared him to all his acquaintances."[18] In the fall of 1857, staying in New York, Morphy played 261 games, both regular and at odds. His overall score in regular games was 87 wins, 8 draws, and 5 losses.[19]

Daniel Fiske recruited Morphy to be co-editor of his Chess Monthly, starting in early 1858 after the Congress, and Morphy held the position until the end of 1860.[20]

Europe

Up to this time, Morphy was not well known or highly regarded in Europe. Despite his dominance of the US chess scene, the quality of his opponents was relatively low compared to Europe, where most of the best chess players lived. European opinion was that they should not have to make the journey to the United States to play a young and relatively unknown player, especially as the US had few other quality players to make such a trip worthwhile.[21]

The American Chess Association, it is reported, are about to challenge any player in Europe to contest a match with the young victor in the late passage at arms, for from $2,000 to $5,000 a side, the place of meeting being New York. If the battle-ground were to be London or Paris, there can be little doubt, we apprehend, that a European champion would be found; but the best players in Europe are not chess professionals, but have other and more serious avocations, the interests of which forbid such an expenditure of time as is required for a voyage to the United States and back again.[22]

— The Illustrated London News, December 26, 1857

Morphy returned to his home city with no further action. The New Orleans Chess Club determined that a challenge should be made directly to the European champion Howard Staunton.

Sir,—On behalf of the New Orleans Chess Club, and in compliance with the instructions of that body, we the undersigned committee, have the honor to invite you to visit our city, and there meet Mr. Paul Morphy in a chess match ...

... it was suggested that Mr. Morphy, the winner at the late Congress and the present American champion, should cross the ocean, and boldly encounter the distinguished magnates of the transatlantic chess circles; but it unfortunately happens that serious family reasons forbid Mr. Morphy, for the present, to entertain the thought of visiting Europe. It, therefore, becomes necessary to arrange, if possible, a meeting between the latter and the acknowledged European champion, in regard to whom there can be no scope for choice or hesitation—the common voice of the chess world pronounces your name ...[23]

— New Orleans Chess Club to Howard Staunton, February 4, 1858

Staunton made an official reply through The Illustrated London News stating that it was not possible for him to travel to the United States and that Morphy must come to Europe if he wished to challenge him and other European chess players.

... The terms of this cartel are distinguished by extreme courtesy, and with one notable exception, by extreme liberality also. The exception in question, however (we refer to the clause which stipulates that the combat shall take place in New Orleans!) appears to us utterly fatal to the match ...

... If Mr. Morphy—for whose skill we entertain the liveliest admiration—be desirous to win his spurs among the chess chivalry of Europe, he must take advantage of his purposed visit next year; he will then meet in this country, in France, in Germany, and in Russia, many champions whose names must be as household words to him, ready to test and do honor to his prowess.[24]

— The Illustrated London News, April 3rd, 1858

Eventually, Morphy went to Europe to play Staunton and other chess greats. Morphy made numerous attempts at setting up a match with Staunton, but none ever came through. Staunton was later criticised for avoiding a match with Morphy, although his peak as a player had been in the 1840s and he was considered past his prime by the late 1850s. Staunton is known to have been working on his edition of the complete works of Shakespeare at the time, but he also competed in a chess tournament during Morphy's visit. Staunton later blamed Morphy for the failure to have a match, suggesting among other things that Morphy lacked the funds required for match stakes—a most unlikely charge given Morphy's popularity. Morphy also remained resolutely opposed to playing chess for money, reportedly due to family pressure.[26]

Seeking new opponents, Morphy crossed the English Channel to France. At the Café de la Régence in Paris, the center of chess in France, Morphy soundly defeated resident chess professional Daniel Harrwitz. In the same place and in another performance of his skills, he defeated eight opponents in blindfolded simultaneous chess.[27]

In Paris, Morphy suffered from a bout of gastroenteritis. In accordance with the medical wisdom of the time, he was treated with leeches, resulting in his losing a significant amount of blood. Although too weak to stand up unaided, Morphy insisted on going ahead with a match against the visiting German master Adolf Anderssen, considered by many to be Europe's leading player. The match between Morphy and Anderssen took place between December 20, 1858, and December 28, 1858, when Morphy was still aged 21.[28] Despite his illness Morphy triumphed easily, winning seven while losing two, with two draws.[29] When asked about his defeat, Anderssen claimed to be out of practice, but also admitted that Morphy was in any event the stronger player and that he was fairly beaten. Anderssen also attested that in his opinion, Morphy was the strongest player ever to play the game, even stronger than the famous French champion La Bourdonnais.[30]

Both in England and France, Morphy gave numerous simultaneous exhibitions, including displays of blindfold chess in which he regularly played and defeated eight opponents at a time.

Hailed as World Chess Champion

Still only 21 years old, Morphy was now quite famous. While in Paris, he was sitting in his hotel room one evening, chatting with his companion Frederick Edge, when they had an unexpected visitor. "I am Prince Galitzin; I wish to see Mr. Morphy", the visitor said, according to Edge. Morphy identified himself to the visitor. "No, it is not possible!" the prince exclaimed, "You are too young!" Prince Galitzin then explained that he was in the frontiers of Siberia when he had first heard of Morphy's "wonderful deeds". He explained, "One of my suite had a copy of the chess paper published in Berlin, the Schachzeitung, and ever since that time I have been wanting to see you." He then told Morphy that he must go to Saint Petersburg, Russia, because the chess club in the Imperial Palace would receive him with enthusiasm.[32]

Morphy offered to play a match with Harrwitz, giving odds of pawn and move, and even offered to find stakes to back his opponent, but the offer was declined.[33] Morphy then declared that he would play no more formal matches, with anyone, without giving at least those odds.[34]

In Europe, Morphy was generally hailed as world chess champion. In Paris, at a banquet held in his honor on April 4, 1859, a laurel wreath was placed over the head of a bust of Morphy, carved by the sculptor Eugène-Louis Lequesne. Morphy was declared by St. Amant "the first Chess player in the whole world".[35] At a similar gathering in London, where he returned in the spring of 1859, Morphy was again proclaimed "the Champion of the Chess World".[36] He may also have been invited to a private audience with Queen Victoria.[37] At a simultaneous match against five masters, Morphy won two games against Jules Arnous de Rivière and Henry Edward Bird, drew two games with Samuel Boden and Johann Jacob Löwenthal, and lost one to Thomas Wilson Barnes.[38]

Upon his return to America, the accolades continued as Morphy toured the major cities on his way home. At the University of the City of New York, on May 29, 1859, John Van Buren, son of President Martin Van Buren, ended a testimonial presentation by proclaiming, "Paul Morphy, Chess Champion of the World".[39] In Boston, at a banquet attended by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Louis Agassiz, Boston mayor Frederic W. Lincoln Jr., and Harvard president James Walker, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes toasted "Paul Morphy, the world's Chess Champion".[40] Morphy's celebrity drew manufacturers who sought his endorsements, newspapers asked him to write chess columns, and a baseball club was named after him.

Morphy was engaged to write a series of chess columns for the New York Ledger, which started in August of 1859. They consisted primarily of annotating games of the La Bourdonnais – McDonnell chess matches of 25 years before, plus a few of Morphy's own games. The column ended in August of 1860.[41]

Abandonment of chess

After returning home in 1859, Morphy intended to start a career in law. He did not immediately cease playing serious chess; for example, on a visit to Cuba in 1864 he played a number of games with leading players of that country, including Celso Golmayo, the champion, all at odds of a knight.[42] But he played in no tournaments or serious matches without giving odds for the rest of his life.

Morphy was late to start his law career.[43] He had not done so by 1861 at the outbreak of the American Civil War. His brother Edward had at the very start joined the army of the Confederacy, whereas his mother and sisters emigrated to Paris.[44] Morphy's Civil War service is a rather gray area. David Lawson states "it may be that he was on Beauregard's staff (Confederate Army) for a short while and that he had been seen at Manassas, as had been reported".[45] Lawson also recounts a story by a resident of Richmond in 1861 who describes Morphy as then being "an officer on Beauregard's staff". Other sources indicate that general Pierre Beauregard considered Morphy unqualified, but that Morphy had indeed applied to him.[46] During the war he lived partly in New Orleans and partly abroad, spending time in Havana (1862, 1864)[47][48] and Paris (1863).[49][50]

Morphy was unable to successfully build a law practice after the war ended in 1865.[51] There are records of at least three attempts to open and advertise a law office, but these were all abandoned.[52] It has been speculated that his celebrity as a chess player worked against him,[53][54] but the reason for the failure can only be guessed. Financially secure thanks to his family's fortune, Morphy essentially spent the rest of his life in idleness. Asked by admirers to return to chess competition, he refused. In 1883 he met Wilhelm Steinitz (who had tried unsuccessfully to get Morphy to agree to a match in the 1860s) in New Orleans, but declined to discuss chess with him.[55]

In accord with the prevailing sentiment of the time, Morphy esteemed chess only as an amateur activity, considering the game unworthy of pursuit as a serious occupation.[56]

Starting around 1875, Morphy showed signs of a persecution complex; he sued his brother-in-law, for example, and tried to provoke a duel with a friend. His best friend Charles Maurian noted in some letters that Morphy was "deranged" and "not right mentally". In 1875, his mother, brother and a friend tried to admit him to a Catholic sanitarium, but Morphy was so well able to argue for his rights and sanity that they sent him away.[57]

Death

On the afternoon of July 10, 1884, Morphy was found dead in his bathtub in New Orleans at the age of 47. According to the autopsy, Morphy had suffered a stroke brought on by entering cold water after a long walk in the midday heat.[58] A lifelong Catholic, Paul Morphy was buried in the family tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana.[59] The Morphy mansion, sold by the family in 1891, later became the site of the restaurant Brennan's.

Ernest Jones published an article of psychoanalytic discussion of Morphy.[60] Reuben Fine published a longer article in which Morphy was mentioned.[61] Both articles have been criticized for the use of unreliable historical sources.[62]

Fine wrote that Morphy "arranged women's shoes into a semi-circle around his bed", and this has been widely copied and embellished upon.[63] But it is a misquotation from a booklet written by Morphy's niece, Regina Morphy-Voitier. She wrote:

Now we come to the room which Paul Morphy occupied, and which was separated from his mother's by a narrow hall. Morphy's room was always kept in perfect order, for he was very particular and neat, yet this room had a peculiar aspect and at once struck the visitor as such, for Morphy had a dozen or more pairs of shoes of all kinds which he insisted in keeping arranged in a semi-circle in the middle of the room, explaining with his sarcastic smile that in this way, he could at once lay his hands on the particular pair he desired to wear. In a huge porte-manteau he kept all his clothes which were at all times neatly pressed and creased.[64]

Morphy's niece's description of Morphy's organization of his own shoes is only a starting point for the lurid descriptions by Fine and subsequent authors.

Playing style

With the white pieces, Morphy usually played 1.e4 and favored gambits, especially the King's Gambit and Evans Gambit, although not exclusively. With the black pieces, Morphy usually answered 1.e4 with 1...e5. The Morphy Defense of the Ruy Lopez (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6) is named after him and remains the most popular variant of that opening. Against 1.d4, he favored the Dutch Defense but also tried the Queen's Gambit Declined.[65] In his notes to the games of the La Bourdonnais – McDonnell chess matches he criticized the Sicilian Defense and Queen's Gambit,[66] and the only known instance where he used a Sicilian Defense was a game against Löwenthal in 1858.[67]

Morphy approached the game more seriously than even the strongest of his contemporaries; as Anderssen noted,

I cannot describe better the impression that Morphy made on me than by saying that he treats chess with the earnestness and conscientiousness of an artist. With us, the exertion that a game requires is only a matter of distraction, and lasts only as long as the game gives us pleasure; with him, it is a sacred duty. Never is a game of chess a mere pastime for him, but always a problem worthy of his steel, always a work of vocation, always as if an act by which he fulfills part of his mission.[68]

Morphy also, according to Garry Kasparov,

became the most erudite player of his time. Fluent in French, English, Spanish, and German, he read Philidor's L'analyse, the Parisian magazine La Régence, Staunton's Chess Player's Chronicle, and possibly also Anderssen's Schachzeitung (at least, he knew all of Anderssen's published games). He studied Bilguer's 400-page Handbuch—which consisted partly of opening analyses in tabular form, and also Staunton's Chess Player's Handbook.[69]

Morphy generally played quickly, but "knew also how to be slow, as in some of his match-games with Anderssen, for instance."[70] Playing in the era before time controls were used, Morphy sometimes faced opponents who played very slowly; Paulsen took over eleven hours for the moves of the second game of their match in the New York 1857 tournament.[71]

Löwenthal and Anderssen both later remarked that Morphy was very hard to beat, since he knew how to defend well and would draw or even win games despite getting into bad positions. At the same time, he was deadly when given a promising position. Anderssen especially commented on this, saying that, after one bad move against Morphy, one might as well resign.[72] "Mr. Morphy wins his games in Seventeen moves, and I in Seventy. But that is only natural", Anderssen said, explaining his poor results against Morphy.[73]

Legacy

Garry Kasparov held that Morphy's historical merit is realizing the relevance of 1) the fast development of the pieces, 2) domination of the center, and 3) opening lines, a quarter-century before Wilhelm Steinitz had formulated those principles. Kasparov maintained that Morphy can be considered both the "forefather of modern chess" and "the first swallow – the prototype of the strong 20th-century grandmaster".[74]

Bobby Fischer ranked Morphy among the ten greatest chess players of all time,[75] and described him as "perhaps the most accurate player who ever lived".[75] He noted that "Morphy and Capablanca had enormous talent",[76] and stated that Morphy had the talent to beat any player of any era if given time to study modern theory and ideas.[75]

Reuben Fine disagreed with Fischer's assessment: "[Morphy's] glorifiers went on to urge that he was the most brilliant genius who had ever appeared. ... But if we examine Morphy's record and games critically, we cannot justify such extravaganza. And we are compelled to speak of it as the Morphy myth. ... He was so far ahead of his rivals that it is hard to find really outstanding examples of his skill... Even if the myth has been destroyed, Morphy remains one of the giants of chess history."[77]

Garry Kasparov,[74] Viswanathan Anand,[78] and Max Euwe argued that Morphy was far ahead of his time. In this regard, Euwe described Morphy as "a chess genius in the most complete sense of the term".[79]

Morphy is frequently mentioned in Walter Tevis's novel The Queen's Gambit and its 2020 Netflix eponymous adaptation, as the favorite player of the main character, a chess prodigy named Beth Harmon.

Results

Games played at odds, blindfold games, and consultation games are not listed.

Notable game results from before the First American Chess Congress:[80]

| Date | Opponent | Won | Lost | Drew | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1849-1850 | Eugène Rousseau | 45 | 5 | 0 | New Orleans | Numbers are estimated. |

| 1849-1852 | James McConnell | 29 | 1 | 0 | New Orleans | |

| 1850 | Johann Löwenthal | 2 | 0 | 1 | New Orleans | |

| 1855 | Alexander Beaufort Meek | 6 | 0 | 0 | Mobile, Alabama | |

| 1855 | T. Ayers | 2 | 0 | 0 | Mobile, Alabama | |

| 1857 | Alexander Beaufort Meek | 4 | 0 | 0 | Mobile, Alabama |

Morphy's tournament games from the First American Chess Congress, 1857:[81]

| Opponent | Won | Lost | Drawn | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Thompson | 3 | 0 | 0 | first round |

| Alexander Beaufort Meek | 3 | 0 | 0 | quarter-final |

| Theodor Lichtenhein | 3 | 0 | 1 | semi-final |

| Louis Paulsen | 5 | 1 | 2 | final |

Morphy's games, played at the First American Chess Congress, 1857, but not in the main tournament:[82][83]

| Opponent | Won | Lost | Drawn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Samuel Robert Calthrop | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Lewis Elkin | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daniel Willard Fiske | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| William James Appleton Fuller | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| George Hammond | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Hiram Kennicott | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Theodor Lichtenhein | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Napoleon Marache | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Charles Mead | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Alexander Beaufort Meek | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Hardman Montgomery | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| David Parry | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Louis Paulsen | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Frederick Perrin | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Benjamin Raphael | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| John William Schulten | 23 | 1 | 0 |

| Moses Solomons | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Charles Henry Stanley | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| James Thompson | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Morphy's match and other games in England, 1858:[84][81]

| Opponent | Won | Lost | Drawn | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edward Löwe | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Thomas Hampton | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Thomas Barnes | 19 | 7 | 0 | |

| Samuel Boden | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| James Kipping | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| George Webb Medley | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Augustus Mongredien | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| John Owen | 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| Johann Löwenthal | 9 | 3 | 2 | Match |

| Henry Edward Bird | 10 | 1 | 1 |

Morphy's matches and other games in France, 1858-1859:[85][81]

| Opponent | Won | Lost | Drawn | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel Harrwitz | 5 | 2 | 1 | Match |

| Paul Journoud | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| Henri Baucher | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Wincenty Budzyński | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Jean Adolphe Laroche | 5 | 0 | 2 | |

| Jules Arnous de Rivière | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

| Adolf Anderssen | 7 | 2 | 2 | Match |

| Adolf Anderssen | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| Augustus Mongredien | 7 | 0 | 1 | Match |

| Franz Schrüfer[86] | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Games played after Morphy's return to the United States:

| Opponent | Won | Lost | Drawn | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johann Löwenthal[87] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1859 | London |

| Félix Sicre[88] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1862 | Havana |

| Jules Arnous de Rivière[89][90] | 13 | 5 | 0 | 1863 | Paris |

Notable games

Louis Paulsen vs. Morphy, New York 1857

Morphy defeats his main rival in the First American Chess Congress. Notes are excerpted from those by Kasparov.[74][91]

Morphy vs. Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard, Paris 1858

This was a well-known casual game against the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard at the Italian Opera House in Paris, 1858. Refer to Opera Game for the game score. Morphy's opponents were not the strongest, but the game was beautiful and instructive, often used by chess teachers to demonstrate how to use tempo, develop pieces, and generate threats.

Morphy vs. Adolf Anderssen, match, Paris 1858

In the ninth game of their match, Morphy launches a sacrificial attack against Anderssen's Sicilian defense, winning in 17 moves. Notes are excerpted from those by Kasparov.[74][92]

See also

- List of chess games

- Morphy Number – connections of chess players to Morphy

Notes

- Edward Winter (December 3, 2022). "The Pride and Sorrow of Chess". Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 10–11.

- Lawson 2010, p. 11.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 11–12.

- Edge 1859, p. 2. "I sorrowfully confess that my hero's unromantic regard for truth makes him characterize the above statement as a humbug and an impossibility".

- Lawson 2010, p. 12.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 13–14.

- Lawson 2010, p. 18.

- Lawson 2010, p. 20.

- Lawson 2010, p. 21.

- Lawson 2010, p. 22.

- One of the games was given as a draw in Sergeant's Morphy's Games of Chess (1957), taken from Löwenthal's collection of Morphy's games (1860), but Lawson (1976) considers that the correct score was that published by other sources, such as the New York Clipper, in 1856, as submitted for publication by Ernest Morphy.

- Fischer, Johannes (October 18, 2017). "50 games you should know: Morphy vs. Duke of Brunswick, Count Isoard". ChessBase. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- Lawson 2010, p. 35.

- Edward Winter, Memory Feats of Chess Masters, Chess Notes 2764 & 2886

- Lawson 2010, p. 41.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 45–46.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 78–79.

- Garry Kasparov (2003). "Chess before Steinitz". My Great Predecessors. Part 1. Everyman Chess. p. 35. ISBN 1-85744-330-6.

Lawson (2010, p. 78) gives 85 wins, 4 losses, and 8 draws. - Lawson 2010, pp. 76–77, 273.

- Edge 1859, pp. 12–16.

- Edge 1859, p. 16.

- Edge 1859, pp. 17–18.

- Edge 1859, pp. 21–22.

- Reichhelm, Gustavus C.; Shipley, Walter Penn, eds. (1898). Chess in Philadelphia. Billstein & Son. Frontispiece.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 120–122, quoting Charles Maurian.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 125–134.

- "Paul Morphy Timeline". edochess.ca.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 170–172.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 177-179 (quoting a letter from Anderssen to von der Lasa).

- Fischer, Johannes (October 18, 2017). "50 games you should know: Morphy vs. Duke of Brunswick, Count Isoard". ChessBase. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- Edge 1859, p. 195.

- Lawson 2010, p. 182.

- Lawson 2010, p. 183.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 201–203, quoting St. Amant in Le Sport.

- Lawson 2010, p. 208.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 214–215.

- Géza Maróczy, Paul Morphy. Sammlung der von ihm gespielten Partien mit ausführlichen Erläuterungen, Veit und Comp., Leipzig 1909, pp. 303-310. Reprinted by Olms-Verlag, Zürich 1979.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 221–225.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 232–233.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 242–244.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 293–294.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 251, 294-298.

- Thomas Eichorn, Karsten Müller and Rainier Knaak, Paul Morphy: Genius and Myth, 2003 ChessBase Gmbh, Hamburg, Germany

- Lawson 2010, p. 280.

- Taylor Kingston, Morphy: More or Less?

- Lawson 2010, pp. 282–283, 293–294.

- Andrés Clemente Vázquez, La odisea de Pablo Morphy en La Habana, La Propaganda Literaria, Habana 1893.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 285–291.

- Jakov Neistadt, Shakhmaty do Steinitza, p. 184, Fizkultura i sport, Moskwa 1961 (Russian edition).

- Lawson 2010, pp. 294-295, 301-303.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 294–298, 301–303.

- Sergeant 1916, p. 25.

- Lawson 2010, p. 303.

- Landsberger, Kurt (2002). The Steinitz Papers. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 39. ISBN 0-7864-1193-7.

- Sergeant 1957, pp. 23, 29.

- Lawson 2010, pp. 303–307.

- Obituary in the Times Democrat 1884

- Louisiana Digital Library (December 13, 2020). "Tomb of Paul Morphy in St. Louis Cemetery #1, New Orleans Louisiana in the 1930s". Louisiana Works Progress Administration of Louisiana. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- Ernest Jones (January 1931). "The Problem of Paul Morphy; A Contribution to the Psycho-Analysis of Chess". International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 12.

- Reuben Fine (1956). "Psychoanalytic Observations on Chess and Chess Masters". Psychoanalysis. 4 (3): 7–77.

Reprinted in book form by Dover as The Psychology of the Chess Player, 1967. - Lawson 2010, pp. 313–319.

- Edward Winter. "'Fun'". Chess Notes.

- Regina Morphy-Voitier, Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New-Orleans and Abroad (1926), p. 38

- Sergeant 1957, pp. 350–351, Index of Openings.

- Sergeant 1957, pp. 24–25.

- "Johann Jacob Loewenthal vs Paul Morphy (1858)". www.chessgames.com.

- Lawson 2010, p. 178, quoting a letter from Anderssen to von der Lasa, translated by Dr. Buschke.

- Garry Kasparov (2003). "Chess before Steinitz". My Great Predecessors, Part 1. Everyman Chess. p. 32.

- Sergeant 1957, p. 33.

- Lawson 2010, p. 59.

- Lawson 2010, p. 175.

- Edge 1859, p. 193.

- Kasparov, Garry (2003). My Great Predecessors, Part I. Everyman Chess. pp. 32–44. ISBN 978-1-85744-330-1.

- Bobby Fischer (January–February 1964). "The ten greatest masters in history". Chessworld. Vol. 1, no. 1. pp. 56–61.

- "Speaking about Fischer..." Chessbase. November 4, 2006.

- Reuben Fine, The World's Great Chess Games (New York: Dover, 1983; reprint of 1976 edition), page 22-23.

- "The Grandmaster on his ten greatest chess players". Archived from the original on November 20, 2003.

- Beim, Valeri (2005). Paul Morphy: A Modern Perspective. Russell Enterprises, Inc. p. .

- "Edo Ratings, Morphy, Paul". www.edochess.ca.

- Lawson 2010, p. 340.

- Lawson 2010, p. 78.

- "Edo Ratings, Morphy, Paul". www.edochess.ca.

- Edge 1859, p. 200.

- Edge 1859, p. 201.

- Sergeant 1957, p. 292.

- Sergeant 1957, pp. 271–274.

- Sergeant 1957, pp. 293–294.

- Sergeant 1957, pp. 294–304.

- "Edo Ratings, Morphy, Paul". www.edochess.ca.

- "Louis Paulsen vs. Paul Morphy, New York 1857". Chessgames.com.

- "Paul Morphy vs. Adolf Anderssen". Chessgames.com.

References

- Lawson, David (1976). Paul Morphy, The Pride and Sorrow of Chess. McKay. ISBN 978-0-679-13044-4. The only book-length biography of Paul Morphy in English, it corrects numerous historical errors that have cropped up.

- Lawson, David (2010). Paul Morphy, The Pride and Sorrow of Chess. University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. ISBN 978-1-887366-97-7. Edited by Thomas Aiello. Includes annotated bibliography of books and articles published since Lawson's original edition. Omits the sixty game scores in Part II of Lawson's original edition.

- Edge, Frederick Milne (1859). Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion. An Account of His Career in America and Europe. D. Appleton and Company. Edge was a newspaperman who attached himself to Morphy during his stay in England and France, accompanying Morphy everywhere, and even acting at times as his unofficial butler and servant. Thanks to Edge, much is known about Morphy that would be unknown otherwise, and many games Morphy played were recorded only thanks to Edge. Contains information about the First American Chess Congress, and the history of English chess clubs in and before Morphy's time.

- Sergeant, Philip W. (1916). Morphy's Games of Chess. London: G. Bell & Sons. Features annotations collected from previous commentators, as well as additions by Sergeant. Has all of Morphy's match, tournament, and exhibition games, and most of his casual and odds games. Short biography included.

- Sergeant, Philip W. (1957). Morphy's Games of Chess. Dover. ISBN 0-486-20386-7. Paperback reprint of Sergeant's original book, with an introduction by Fred Reinfeld.

Further reading

- Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory by Macon Shibut, Caissa Editions 1993 ISBN 0-939433-16-8. Over 415 games comprising almost all known Morphy games. Chapters on Morphy's place in the development of chess theory, and reprinted articles about Morphy by Steinitz, Alekhine, and others.

- The Chess Genius of Paul Morphy by Max Lange (translated from the original German into English by Ernst Falkbeer), 1860. Reprinted by Moravian Chess under the title, "Paul Morphy, a Sketch from the Chess World". An excellent resource for the European view of Morphy as well as for its biographical information. The English edition was reviewed in Chess Player's Chronicle, 1859.

- Paul Morphy. Sammlung der von ihm gespielten Partien mit ausführlichen Erläuterungen by Géza Maróczy, Veit und Comp., Leipzig 1909. Reprinted by Olms-Verlag, Zürich 1979.

- Grandmasters of Chess by Harold Schonberg, Lippincott, 1973. ISBN 0-397-01004-4.

- World Chess Champions by Edward Winter, editor, 1981. ISBN 0-08-024094-1. Leading chess historians include Morphy as a de facto world champion, although he never claimed the title.

- Morphy's Games of Chess by J Löwenthal, London, 1860, Henry Bohn. Features a short memoir, 1 page intro from Morphy with analytical notes from Löwenthal, including blindfold and handicap games.

- Morphy Gleanings by Philip W. Sergeant, David McKay, 1932. Contributes games not found in Sergeant's earlier work, "Morphy's Games of Chess" and features greater biographical information as well as documentation into the Morphy–Paulsen and the Morphy–Kolisch affairs. Later reprinted as "The Unknown Morphy", Dover, 1973. ISBN 0-486-22952-1.

- The World's Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine, Dover, 1983. ISBN 0-486-24512-8.

- A First Book of Morphy by Frisco Del Rosario, Trafford, 2004. ISBN 1-4120-3906-1. Illustrates the teachings of Cecil Purdy and Reuben Fine with 65 annotated games played by the American champion. Algebraic notation.

- Paul Morphy: A Modern Perspective by Valeri Beim, Russell Enterprises, Inc., 2005. ISBN 1-888690-26-7. Algebraic notation.

- Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New-Orleans and Abroad by Regina Morphy-Voitier, 1926. Regina Morphy-Voitier, the niece of Paul Morphy, self-published this pamphlet in New York.

- The Chess Players by Frances Parkinson Keyes, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy; 1960. A work of historical fiction in which Morphy is the central character.

- Paul Morphy: Confederate Spy, by Stan Vaughan, Three Towers Press, 2010. A work of historical fiction in which Morphy is the central character.

- . Chess Player's Chronicle. Third Series: 40. 1860.

- The Genius of Paul Morphy by Chris Ward, Cadogan Books, 1997. ISBN 978-1-85744-137-6. Biographical novelization of Morphy's life.

- La odisea de Pablo Morphy en la Habana, 1862–1864 by Andrés Clemente Vázquez, Propaganda Literaria, Havana 1893.

- Paul Morphy. Partidas completas by Rogelio Caparrós, Ediciones Eseuve, Madrid 1993. ISBN 84-87301-88-6.

External links

- Paul Morphy player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Edward Winter, Edge, Morphy and Staunton

- Morphy's column for the New York Ledger in 1859

- US Chess Hall Of Fame – Paul Morphy

- THE LIFE AND CHESS OF PAUL MORPHY, edochess

- Krabbé, Tim. "The full Morphy". www.xs4all.nl. Complete collection of surviving game scores.