Pećanac Chetniks

During World War II, Pećanac Chetniks, also known as the Black Chetniks, were a collaborationist Chetnik irregular military force which operated in the German-occupied territory of Serbia under the leadership of vojvoda Kosta Pećanac. They were loyal to the Government of National Salvation, the German-backed Serbian puppet government.

| Pećanac Chetniks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1941–43 |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Irregular forces |

| Role | Anti-partisan operations |

| Size | 3,000–6,000 |

| Nickname(s) | Black Chetniks |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Kosta Pećanac |

The Yugoslav government-in-exile eventually denounced Pećanac as a traitor, and the Germans concluded that his detachments were inefficient, unreliable, and of little military value to them. The Germans and the puppet government disbanded the organisation between September 1942 and March 1943. The Serbian puppet regime interned Pećanac for some time afterwards; forces loyal to his Chetnik rival Draža Mihailović killed him in mid-1944.

Background

The Pećanac Chetniks were named after their commander, Kosta Pećanac, who was a fighter and later vojvoda in the Serbian Chetnik Organization who had first distinguished himself in fighting against the Ottoman Empire in Macedonia between 1903 and 1910.[1][2][3] In the First Balkan War, fought from October 1912 to May 1913, Pećanac served as a sergeant in the Royal Serbian Army.[3] During the Second Balkan War, fought from 29 June to 10 August 1913, he saw combat against the Kingdom of Bulgaria.[4] During World War I, he led bands of Serbian guerillas fighting behind Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian lines.[5]

He was the most prominent figure in the Chetnik movement during the interwar period. He had a leading role in the Association Against Bulgarian Bandits, a notorious organisation that arbitrarily terrorised Bulgarians in the Štip region, part of modern-day Macedonia.[6] He also served as a commander with the Organization of Yugoslav Nationalists (ORJUNA).[7] As a member of parliament, he was present when the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) leader Stjepan Radić and HSS deputies Pavle Radić and Đuro Basariček were killed by the Serb politician Puniša Račić on 20 June 1928. Prior to the shooting, Pećanac was accused by HSS deputy Ivan Pernar of being responsible for a massacre of 200 Muslims in 1921.[8]

Pećanac became the president of the Chetnik Association in 1932.[9] By opening membership of the organisation to younger members that had not served in World War I, he grew the organisation during the 1930s from a nationalist veterans' association focused on protecting veterans' rights to an aggressively partisan Serb political organisation with 500,000 members throughout the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[10] During this period, Pećanac formed close ties with the far-right Yugoslav Radical Union government of Milan Stojadinović,[11] and was known for his hostility to the Yugoslav Communist Party, which made him popular with conservatives such as those in the Yugoslav Radical Union.[12][13]

Formation

Shortly before the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the Yugoslav Ministry of the Army and Navy requested that Pećanac prepare for guerrilla operations and guard the southern area of Serbia, Macedonia, and Kosovo from pro-Bulgarians and pro-Albanians in the region. He was given arms and money, and managed to arm several hundred men in the Toplica River valley in southern Serbia. Pećanac's force remained intact after the German occupation of Serbia and supplemented its strength from Serb refugees fleeing Macedonia and Kosovo. In the early summer of 1941, Pećanac's detachments fought against Albanian bands.[9] At this time and for a considerable period after, only detachments under Pećanac were identified by the term "Chetnik".[14] With the formation of the communist-led Yugoslav Partisans, Pećanac gave up any interest in resistance, and by late August came to agreements with both the Serbian puppet government and the German authorities to carry out attacks against the Partisans.[14][15]

Pećanac kept the organisational structure of his detachments simple. All of the commanders were selected personally by Pećanac and consisted of former officers, peasants, Orthodox priests, teachers, and merchants.[14] The Pećanac Chetniks were also known as the "Black Chetniks".[16]

Collaboration with occupation and quisling forces

On 18 August 1941, while he was concluding arrangements with the Germans, Pećanac received a letter from rival Chetnik leader Draža Mihailović proposing an arrangement where Pećanac would control the Chetniks south of the Western Morava River while Mihailović would control the Chetniks in all other areas.[17] Pećanac declined this request and suggested that he might offer Mihailović the position as his chief of staff. He also recommended that Mihailović's detachments disband and join his organisation. In the meantime, Pećanac had arranged for the transfer of several thousand of his Chetniks to the Serbian Gendarmerie to act as German auxiliaries.[18]

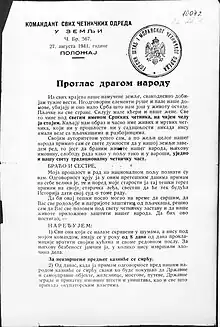

On 27 August, Pećanac issued an open "Proclamation to the Dear People", in which he portrayed himself as the defender and protector of Serbs and, referring to Mihailović's units, called on "detachments that have been formed without his approval" to come together under his command. He demanded that individuals hiding in the forests return to their homes immediately and that acts of sabotage directed at the occupation authorities cease or suffer the punishment of death.[19] The communist leader Josip Broz Tito and all members of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia left Belgrade on 16 September 1941 using documents issued to Tito by Dragoljub Milutinović who was voivode of Pećanac Chetniks.[20] Since Pećanac was already fully cooperating with the Germans by this time, this assistance caused some to speculate that Tito left Belgrade with the blessing of the Germans because his task was to divide the rebel forces, similar to Lenin's arrival in Russia.[21]

In September 1941, some of Pećanac's subordinates broke ranks to join the Partisans in fighting the Germans and their Serbian auxiliaries. In the mountainous Kopaonik region, a previously loyal subordinate of Pećanac began attacking local gendarmerie stations and clashing with armed bands of Albanian Muslims. By the end of October the Germans decided to stop arming the "unreliable" elements within Pećanac's Chetniks, and attached the remainder to their other Serbian auxiliary forces.[22]

On 7 October 1941, Pećanac sent a request to the head of the Serbian puppet government, Milan Nedić, for trained officers, supplies, arms, salary funds, and more. Over time his requests were fulfilled, and a German liaison officer was appointed at Pećanac's headquarters to help coordinate actions. On 17 January 1942, according to German data, 72 Chetnik officers and 7,963 men were being paid and supplied by the Serbian Gendarmerie. This fell short of their maximum authorised strength of 8,745 men, and included two or three thousand of Mihailović's Chetniks who had been "legalised" in November 1941.[14] In the same month, Pećanac sought permission from the Italians for his forces to move into eastern Montenegro, but was refused due to Italian concerns that the Chetniks would move into the Sandžak.[23]

In April 1942, the German Commanding General in Serbia, General der Artillerie[lower-alpha 1] Paul Bader, issued orders giving the unit numbers C–39 to C–101 to the Pećanac Chetnik detachments, which were placed under the command of the local German division or area command post. These orders required the deployment of a German liaison officer with all detachments engaged in operations, and also limited their movement outside their assigned area. Supplies of arms and ammunition were also controlled by the Germans.[25] In July 1942, Mihailović arranged for the Yugoslav government-in-exile to denounce Pećanac as a traitor,[26] and his continuing collaboration ruined what remained of the reputation he had developed in the Balkan Wars and World War I.[16]

Pećanac Chetniks committed some of the cruelest crimes of collaborationist troops, even if they are responsible for less murders than members of Mihailović's Chetniks and other German auxiliaries such as the Serbian State Guard and Serbian Volunteer Command. Crimes of the largest scale occurred in the villages of Melovo and Mijovac, near Leskovac on 5 and 6 February 1942. Pećanac Chetniks killed eight members of the same Romani family in Melovo, which included killing children. In the next days the same force shot 44 Romani civilians in Mijovac, including women and children.[27] Pećanac Chetniks also arrested other Romani people and handed them over to the Germans.[28] Any Yugoslav Partisans and their sympathizers were either executed by Pećanac's forces when captured or they were handed over to the Germans who either shot them or sent them to internment camps.[29]

Dissolution

The Germans found that Pećanac's units were inefficient, unreliable, and of little military aid to them. Pećanac's Chetniks regularly clashed and had rivalries with other German auxiliaries such as the Serbian State Guard and Serbian Volunteer Command and also with Mihailović's Chetniks.[30] The Germans and the puppet government commenced disbanding them in September 1942, and all but one had been dissolved by the end of that year. The last detachment was disbanded in March 1943. Pećanac's followers were dispersed to other German auxiliary forces, German labour units, or were interned in prisoner-of-war camps. Many deserted to join Mihailović. Nothing is recorded of Pećanac's activities in the months that followed except that he was interned for some time by the Serbian puppet government.[31] Accounts of Pećanac's capture and death vary. According to one account, Pećanac, four of his leaders and 40 of their followers were captured by forces loyal to Mihailović in February 1944. All were killed within days except Pećanac, who remained in custody to write his war memoirs before being executed on 5 May 1944.[30] Another source states he was assassinated on 6 June 1944 by Chetniks loyal to Mihailović.[32]

Notes

- Equivalent to a U.S. Army lieutenant general[24]

Footnotes

- Pavlović, Mladenović & 4 May 2003.

- Pavlović, Mladenović & 5 May 2003.

- Pavlović, Mladenović & 8 May 2003.

- Pavlović, Mladenović & 11 May 2003.

- Mitrović 2007, pp. 248–259.

- Ramet 2006, p. 47.

- Newman 2012, p. 158.

- Glenny 2012, p. 410.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 126.

- Singleton 1985, p. 188.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 52.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 19.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 120.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 127.

- Roberts 1973, p. 21.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 59.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 127–128.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 183.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 128.

- Nikolić, Kosta (2003). Dragan Drašković, Radomir Ristić (ed.). Kraljevo in October 1941. Kraljevo: National Museum Kraljevo, Historical Archive Kraljevo. p. 29.

- Nikolić, Kosta (2003). Dragan Drašković, Radomir Ristić (ed.). Kraljevo in October 1941. Kraljevo: National Museum Kraljevo, Historical Archive Kraljevo. p. 30.

- Milazzo 1975, pp. 28–29.

- Milazzo 1975, pp. 44–45.

- Stein 1984, p. 295.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 195.

- Roberts 1973, p. 63.

- Radanović 2016, p. 301.

- Radanović 2016, p. 298.

- Radanović 2016, p. 293.

- Lazić 2011, pp. 29–30.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 128, 195.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 260.

References

Books

- Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: 1804–2012. London, England: Granta Books. ISBN 978-1-77089-273-6.

- Lazić, Sladjana (2011). "The Collaborationist Regime of Milan Nedić". In Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola (eds.). Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–43. ISBN 978-0-230-27830-1.

- Milazzo, Matteo J. (1975). The Chetnik Movement & the Yugoslav Resistance. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1589-8.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-476-7.

- Newman, John Paul (2012). "Paramilitary Violence in the Balkans". In Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John (eds.). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe After the Great War. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 145–162. ISBN 978-0-19-968605-6.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2007). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Roberts, Walter R. (1973). Tito, Mihailović and the Allies 1941–1945. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0773-0.

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Stein, George H. (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–45. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- Radanović, Milan (2016). Kazna i zločin: Snage kolaboracije u Srbiji. Belgrade: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

Websites

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (4 May 2003). "Zakletva na hleb i revolver". Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian).

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (5 May 2003). "Voskom zavaravali glad". Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian).

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (8 May 2003). "U ratu protiv Turske". Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian).

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (11 May 2003). "Drugi balkanski rat". Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian).