Treaty of Portsmouth

The Treaty of Portsmouth is a treaty that formally ended the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. It was signed on September 5, 1905,[1] after negotiations from August 6 to August 30, at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, United States (at the time considered part of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, however). U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was instrumental in the negotiations and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

Background

The war of 1904–1905 was fought between the Russian Empire, an international power with one of the largest armies in the world, and the Empire of Japan, a nation that had only recently industrialized after two-and-a-half centuries of isolation. A series of battles in the Liaodong Peninsula had resulted in Russian armies being driven from southern Manchuria, and the Battle of Tsushima had resulted in a cataclysm for the Imperial Russian Navy. The war was unpopular in Russia, whose government was under increasing threat of revolution at home. On the other hand, the Japanese economy was severely strained by the war, with rapidly mounting foreign debts, and Japanese forces in Manchuria faced the problem of ever-extending supply lines. No Russian territory had been seized, and the Russians continued to build up reinforcements via the Trans-Siberian Railway. Recognizing that a long war was not to Japan's advantage, the Japanese government as early as July 1904 had begun seeking out intermediaries to assist in bringing the war to a negotiated conclusion.[2]

The intermediary approached by the Japanese was U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had publicly expressed a pro-Japanese stance at the beginning of the war. However, as the war progressed, Roosevelt had begun to show concerns on the strengthening military power of Japan and its long-term impact on U.S. interests in Asia. In February 1905, Roosevelt sent messages to the Russian government via the U.S. ambassador in Saint Petersburg. Initially, the Russians were unresponsive, with Tsar Nicholas II still adamant that Russia would eventually prove victorious. The Japanese government was also lukewarm to a peace treaty, as Japanese armies were enjoying an unbroken string of victories. However, after the Battle of Mukden, which was extremely costly to both sides in terms of manpower and resources, Japanese Foreign Minister Komura Jutarō judged that it was now critical for Japan to push for a settlement.[2]

On March 8, 1905, Japanese Army Minister Terauchi Masatake met with the American Minister to Japan, Lloyd Griscom, to tell Roosevelt that Japan was ready to negotiate. However, a positive response did not come from Russia until after the loss of the Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima. Two days later, Nicholas met with his grand dukes and military leadership and agreed to discuss peace. On June 7, 1905, Roosevelt met with Kaneko Kentarō, a Japanese diplomat, and on June 8, he received a positive reply from Russia. Roosevelt chose Portsmouth, New Hampshire, as the site for the negotiations, primarily because the talks were to begin in August, and the cooler climate in Portsmouth would avoid subjecting the parties to the sweltering Washington summer.[2]

Portsmouth Peace Conference

The Japanese delegation to the Portsmouth Peace Conference was led by Foreign Minister Komura Jutarō and assisted by Ambassador Takahira Kogorō. The Russian delegation was led by former Finance Minister Sergei Witte, who was assisted by the former Ambassador to Japan Roman Rosen and the international law and arbitration specialist Friedrich Martens.[3] The delegations arrived in Portsmouth on August 8 and stayed in New Castle, New Hampshire, at the Hotel Wentworth, where the armistice was signed. They were ferried across the Piscataqua River every day to the naval base in Kittery, Maine, where the negotiations were held.

The negotiations took place at the General Stores Building (now Building 86). Mahogany furniture patterned after the Cabinet Room of the White House was ordered from Washington.

Before the negotiations began, Tsar Nicholas had adopted a hard line and forbidden his delegates to agree to any territorial concessions, reparations, or limitations on the deployment of Russian forces in the Far East.[2] The Japanese initially demanded recognition of their interests in Korea, the removal of all Russian forces from Manchuria, and substantial reparations. They also wanted confirmation of their control of the island of Sakhalin, which Japanese forces had seized in July 1905, partly to use as a bargaining chip in the negotiations.[2]

A total of twelve sessions were held between August 9 and August 30. During the first eight sessions, the delegates were able to reach an agreement on eight points. These included an immediate ceasefire, recognition of Japan's claims to Korea, and the evacuation of Russian forces from Manchuria. Russia also ceded its leases in southern Manchuria (containing Port Arthur and Talien) to Japan and turned over the South Manchuria Railway and its mining concessions to Japan. Russia was allowed to retain the Chinese Eastern Railway in northern Manchuria.[2]

The remaining four sessions addressed the most difficult issues: reparations and territorial concessions. On August 18, Roosevelt proposed that Rosen offer to divide Sakhalin to address the territory issue. On August 23, however, Witte proposed that the Japanese keep Sakhalin and drop their claims for reparations. When Komura rejected the proposal, Witte warned that he was instructed to cease negotiations and that the war would resume. The ultimatum came as four new Russian divisions arrived in Manchuria, and the Russian delegation made an ostentatious show of packing their bags and preparing to depart.[3] Witte was convinced that the Japanese could not afford to restart the war and so applied pressure via the American media and his American hosts[3] to convince the Japanese that monetary compensation was not open for compromise by Russia.[4] Outmaneuvered by Witte, Komura yielded, and in exchange for the southern half of Sakhalin, the Japanese dropped their claims for reparations.[2]

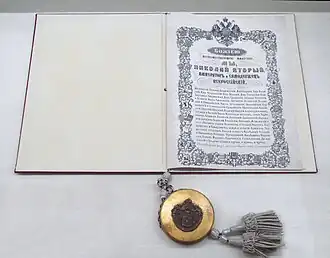

The Treaty of Portsmouth was signed on September 5. The treaty was ratified by the Privy Council of Japan on October 10,[5] and in Russia on October 14, 1905.

Aftermath

The signing of the treaty created three decades of peace between the two nations and confirmed Japan's emergence as the pre-eminent power in East Asia. Born from the Taft–Katsura agreement, the treaty gave consent to the Japanese colonization of Korea, and later resulted in the annexation of Korea to Japan in 1910.

The treaty also forced Russian Empire to abandon its expansionist policies in East Asia, but it was not well received by the Japanese people.[6] The Japanese public were aware of their country's unbroken string of military victories over the Russians but were less aware of the precarious overextension of military and economic power that the victories had required. News of the terms of the treaty appeared to show Japanese weakness in front of the European powers, and this frustration caused the Hibiya riots and the collapse of First Katsura Cabinet (first premiership of Katsura Tarō) on January 7, 1906.[2]

Because of the role played by Theodore Roosevelt, the United States became a significant force in world diplomacy. President Roosevelt was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for his backchannel efforts before and during the peace negotiations even though he never actually went to Portsmouth.

Treaty Building in 1912

Treaty Building in 1912 Envoy reception

Envoy reception Key to envoy reception

Key to envoy reception Hotel Wentworth, c. 1906

Hotel Wentworth, c. 1906

Criticism

Korean historians (such as Ki-baik Lee, author of A New History of Korea, Harvard University Press, 1984) believe that the Treaty of Portsmouth violated the Korean–American Treaty of Amity and Commerce signed at Incheon on May 22, 1882, because the Joseon government considered that treaty constituted a de facto mutual defense treaty, unlike the Americans. The problem was Article 1: "There shall be perpetual peace and friendship between the President of the United States and the King of Chosen and the citizens and subjects of their respective Governments. If other powers deal unjustly or oppressively with either Government, the other will exert their good offices on being informed of the case to bring about an amicable arrangement, thus showing their friendly feelings."

The treaty has been cited in contemporary South Korea by some as an example that the United States cannot be relied upon with regards to issues of South Korean security and sovereignty.[7]

Commemoration

In 1994, the Portsmouth Peace Treaty Forum was created by the Japan-America Society of New Hampshire to commemorate the Portsmouth Peace Treaty with the first formal meeting between Japanese and Russian scholars and diplomats in Portsmouth since 1905. As the Treaty of Portsmouth was one of the most powerful symbols of peace in the Northern Pacific region and the most significant shared peace history of Japan, Russia, and the United States, the forum was designed to explore from the Japanese, Russian, and American perspectives, the history of the Portsmouth Treaty and its relevance to current issues involving the Northern Pacific region. The forum is intended to focus modern scholarship on international problems in the "spirit of the Portsmouth Peace Treaty."[8]

References

- "Text of Treaty; Signed by the Emperor of Japan and Czar of Russia", The New York Times. October 17, 1905.

- Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, pp. 300–304.

- Jukes, The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905, pp. 86–90.

- White, J. A.: "Portsmouth 1905: Peace or Truce?", Journal of Peace Research, 6(4):362

- "Partial record of Privy Council meeting to ratify the treaty (from the National Archives of Japan)".

- "Japan's Present Crisis and Her Constitution; The Mikado's Ministers Will Be Held Responsible by the People for the Peace Treaty – Marquis Ito May Be Able to Save Baron Komura," New York Times. September 3, 1905.

- Yun Ho-u 윤호우, "'Katcheura-Taepeuteu Miryak'eun hyeonjae jinhaenghyeong" '가쯔라-태프트 밀약'은 현재진행형 (Katsura-Taft Agreement is Present Progressive), Gyeonghyang dat keom 경향닷컴 (Kyunghyang.com), September 6, 2005 (in Korean).

- See "The First Portsmouth Peace Treaty Forum June 15, 1994" (2005) online Archived 2019-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Davis, Richard Harding, and Alfred Thayer Mahan (1905). The Russo-Japanese War; A Photographic and Descriptive Review of the Great Conflict in the Far East, Gathered from the Reports, Records, Cable Despatches, Photographs, etc., etc., of Collier's War Correspondents. New York: P. F. Collier & Son. OCLC 21581015

- De Martens, F. (1905). "The Portsmouth Peace Conference". The North American Review, 181 (558).

- Doleac, Charles B. (2006). "An Uncommon Commitment to Peace: Portsmouth Peace Treaty 1905".

- Harcave, Sidney (2004). Count Sergei Witte and the Twilight of Imperial Russia: A Biography. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1422-3 (cloth).

- Jukes, Geoffrey (2002). The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7 (paper).

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- Kokovtsov, Vladimir (1935). Out of My Past (Laura Matveev, translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Korostovetz, J. J. (1920). Pre-War Diplomacy: The Russo-Japanese Problem. London: British Periodicals Limited.

- Matsumura, Masayoshi (1987). Nichi-Ro senso to Kaneko Kentaro: Koho gaiko no kenkyu. Shinyudo. ISBN 4-88033-010-8, translated by Ian Ruxton as Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War: A Study in the Public Diplomacy of Japan (2009) ISBN 978-0-557-11751-2 Preview

- Randall, Peter (1985, 2002). There Are No Victors Here: A Local Perspective on the Treaty of Portsmouth. Portsmouth Marine Society.

- Trani, Eugene P. (1969). The Treaty of Portsmouth; An Adventure in American Diplomacy. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

- White, J. A. (1969). "Portsmouth 1905: Peace or Truce?" Journal of Peace Research, 6(4).

- Witte, Sergei (1921). The Memoirs of Count Witte (Abraham Yarmolinsky, translator). New York: Doubleday.

- Witte, Sergei (1990). The Memoirs of Count Witte (Sidney Harcave, translator). Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-87332-571-4 (cloth)

- Yoshimura, Akira (1979). The Flags of Portsmouth (Pōtsumasu no hata – ポーツマスの旗) (French translation published in 1990 under the title 'Les drapeaux de Portsmouth, éditions Philippe Picquier).

External links

- (in French) Text of the treaty, in French

- Copy of the protocols of the conference at the Library of Congress

- The Treaty of Portsmouth, 1905, Russo-Japanese War (actual text)

- Portsmouth Peace Treaty website of the Japan-America Society of New Hampshire Archived 2019-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

- The Museum Meiji Mura

- Imperial rescript endorsing the treaty of Portsmouth (from the National Archives of Japan)