Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition

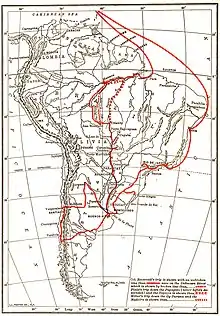

The Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition (Portuguese: Expedição Científica Rondon–Roosevelt) was a survey expedition in 1913–14 to follow the path of the Rio da Dúvida ("River of Doubt") in the Amazon basin. The expedition was jointly led by Theodore Roosevelt, the former president of the United States, and Colonel Cândido Rondon, a Brazilian explorer who had discovered its headwaters in 1909. Sponsored in part by the American Museum of Natural History, they also collected many new animal and insect specimens. The river was eventually named "Rio Roosevelt" for the former president. He nearly died during the voyage and his health was permanently damaged.[1]

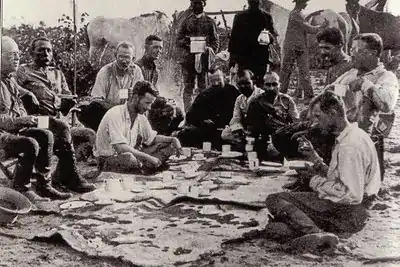

The initial members. From left to right (seated): Father Zahm, Rondon, Kermit, Cherrie, Miller, four Brazilians, Roosevelt, Fiala. Only Roosevelt, Kermit, Cherrie, Rondon and the Brazilians would descend the River of Doubt. | |

| Date | December 1913 – April 1914 |

|---|---|

| Location | River of Doubt (now Roosevelt River), Brazil |

| Participants | Theodore Roosevelt Cândido Rondon Kermit Roosevelt George Kruck Cherrie |

| Outcome | Successful exploration of the River of Doubt |

| Deaths | 3 |

Beginnings

After losing a bid for a third presidential term in the 1912 election, Roosevelt had originally planned to go on a speaking tour of Argentina and Brazil, followed by a cruise of the Amazon River organized by his friend Father John Augustine Zahm. Instead, the government of Brazil suggested that Roosevelt accompany famous Brazilian explorer Cândido Rondon on his exploration of the previously unknown River of Doubt, the headwaters of which had only recently been discovered. Roosevelt, seeking adventure and challenge after his recent electoral defeat, agreed. Kermit Roosevelt, Theodore's son, had recently become engaged and did not plan on joining the expedition but did on the insistence of his mother Edith Roosevelt, in order to protect his father. The expedition started in Cáceres, a small town on the Paraguay River, in December 1913. They traveled to Tapirapuã, where Rondon had previously discovered the headwaters of the River of Doubt. From Tapirapuã, the expedition traveled northwest, through dense forests and then later through the plains on top of the Parecis plateau. They reached the River of Doubt on February 27, 1914. At this point, due to a lack of food supplies, the Expedition split up, with part of the Expedition, including Father Zahm and expedition quartermaster Anthony Fiala, following the Ji-Paraná River to the Madeira River. The remaining party – the Roosevelts, Colonel Rondon, American naturalist George Kruck Cherrie, and 15 Brazilian porters (camaradas) – then started down the River of Doubt.

Problems

Almost from the start, the expedition was fraught with problems. Insects and disease such as malaria weighed heavily on just about every member of the expedition, leaving them in a constant state of sickness, festering wounds and high fevers. The heavy dug-out canoes were unsuitable to the constant rapids and were often lost, requiring days to build new ones. The food provisions were ill-conceived forcing the team on starvation diets. The native Cinta Larga tribe shadowed the expedition and were a constant source of concern – the natives could have at any time wiped out the expedition and taken their valuable metal tools, but they chose to let them pass. (Future expeditions in the 1920s were not so lucky.)

Of the 19 men who went on the expedition, 16 returned. One died by accidental drowning in rapids (with his body never recovered). And

- in early April, a porter named Julio shot and killed another Brazilian who had caught him stealing food. After failing to capture the murderer, the exhausted expedition simply abandoned him in the jungle.[2]

By the time the expedition had made it only about one-quarter of the way down the river, they were physically exhausted and sick from starvation, disease, and the constant labor of hauling canoes around rapids. By its end, everyone on the expedition except for Colonel Rondon was either sick, injured, or both. Roosevelt himself was near death, having received a gash in his leg that had become infected, and the party feared for his life each day. Luckily, they came upon seringueiros ("rubber men"), impoverished rubber-tappers who earned a marginal living from the forest trees driven by the new demand for rubber tires for automobiles. The seringueiros helped the team down the rest of the river (less rapid-prone than the upper reaches). The expedition was reunited on April 26, 1914, with a Brazilian and American relief party led by Lieutenant Antonio Pyrineus, an officer from Rondon's Telegraph Commission. The party had been pre-arranged by Rondon to meet them at the confluence with the Aripuana River, where they had hoped to emerge from the tributary. Medical attention was given to Roosevelt as the group returned to Manaus. Three weeks later, a greatly weakened Roosevelt made it home to a hero's welcome in New York. His health never fully recovered after the trip, and he died less than five years later of related causes.[3]

Confirmation

After Roosevelt returned, there was some doubt that he had actually discovered the river and made the expedition. Even though he was still quite weak and barely able to speak above a whisper, Roosevelt, angry that his credibility had been challenged, arranged speaking engagements with the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., on May 26, and the Royal Geographical Society in London in mid-June. These appearances largely stifled the criticisms at the time.[4] To finally settle the dispute, in 1927 British explorer George Miller Dyott led a second trip down the river, confirming Roosevelt's discoveries.[5]

In 1992 a third (modern) expedition was organized and led by Charles Haskell and Elizabeth McKnight, and sponsored in part by the Theodore Roosevelt Association, the American Museum of Natural History, the National Wildlife Federation and a private trust set up by Haskell and McKnight.[6]

The expedition consisted of a total of twenty persons including Roosevelt's great-grandson Tweed Roosevelt, professional river guides Joe Willie Jones, Kelley Kalafatich, Jim Slade, and Mike Boyle, photographers Carr Clifton and Mark Greenberg, cinematographer Joe Kaminsky, Haskell's son Charles 'Chip' Haskell Jr. who served as the expedition's communications expert, Brazilian scientists Geraldo Mendes dos Santos and João Ferraz (ichthyologist and pharmacologist), chiefs Oita Mina and Tatataré of the Cinta Larga tribe whose land borders much of the river, and the journalist Sam Moses, who was contracted to write a book which was not published because Haskell and McKnight declined to approve the manuscript.

The expedition took 33 days to complete the nearly 1000 mile journey. Whereas the Roosevelt–Rondon Expedition had to portage almost all of the many rapids on the river with their heavy dugout canoes, the Haskel–McKnight Expedition was able to safely navigate all of the rapids except for three which were portaged. Haskell reported that his expedition "found spots chronicled by the original team, saw plants and insects they described, and went down the rapids that crushed the dugout canoes of 1914".

The expedition members were awarded the Theodore Roosevelt Association's Distinguished Service Medal for their achievement.[7] A documentary of the expedition was subsequently produced and aired on PBS called the New Explorers: The River of Doubt narrated by Bill Kurtis and Wilford Brimley.[8] Since this time, the expedition has inspired others to undergo its challenges such as Materials Scientist Professor Marc A. Meyers, Col Huram Reis, Col Ivan Angonese, and Jeffery Lehmann.[9]

Representation in other media

- On September 26, 2021, The American Guest, a four-episode Brazilian miniseries, was released on HBO Latin America and later on HBO Max. The series written by Matthew Chapman and directed by Bruno Barreto follows the expedition of former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt, played by Aidan Quinn, alongside Brazilian army officer Cândido Rondon, portrayed by Chico Diaz.[10]

Notes

- Morris, pp 305–347.

- Andrews, Evan. "The Amazonian Expedition That Nearly Killed Theodore Roosevelt". Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- Millard (2005).

- Millard (2005)

- "River of Doubt", Time Magazine, June 6, 1927.

- "In T. R.'s Footsteps, Scientists Embark on Amazonian Expedition", "Explorers of Amazon Branch Retrace Roosevelt Expedition"

- "Distinguished Service Medal"

- "The New Explorers: River of Doubt"

- "UCSD Explorer Struggling in Amazon"

- "HBO Max Press Room".

Sources and further reading

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Through the Brazilian Wilderness. Wikisource

- Baker, Daniel, ed. (1993). Explorers and Discoverers of the World. Detroit: Gale Research. ISBN 0-8103-5421-7.

- Millard, Candice (2005). The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50796-8.

- Morris, Edmund (2010). Colonel Roosevelt. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50487-7.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1914). Through the Brazilian Wilderness. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 485541.

- Robbins, Gary (October 24, 2014). "UCSD Explorer Struggling in Amazon". The San Diego Union-Tribune. San Diego. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- Wasserman, Renata. "Exotic science and domestic exoticism: Theodore Roosevelt and J.A. Leite Moraes in Amazonia." Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies 57 (2009): 59-78. online

External links

- Works about the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition at Open Library

- The Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific-Expedition and the Telegraph Line Commission by Colonel Cândido Rondon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)