Yellow perch

The yellow perch (Perca flavescens), commonly referred to as perch, striped perch or preacher is a freshwater perciform fish native to much of North America. The yellow perch was described in 1814 by Samuel Latham Mitchill from New York. It is closely related, and morphologically similar to the European perch (Perca fluviatilis); and is sometimes considered a subspecies of its European counterpart.[4]

| Yellow perch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Percidae |

| Genus: | Perca |

| Species: | P. flavescens |

| Binomial name | |

| Perca flavescens (Mitchill, 1814) | |

| |

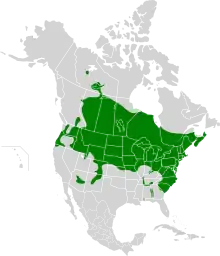

| Native range of yellow perch | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Latitudinal variability in age, growth rates, and size have been observed among populations of yellow perch, likely resulting from differences in day length and annual water temperatures. In many populations, yellow perch often live 9 to 10 years, with adults generally ranging from 4 to 10 in (10 to 25 cm) in length.

The world record for a yellow by weight is 4 lb 3 oz (1.9 kg)), and was caught in May 1865 in Bordentown, New Jersey by Dr. C. Abbot.[5] It is the longest-standing record for a freshwater fish in North America.[6]

Description

The yellow perch has an elongate, laterally compressed body[4] with a subterminal mouth[7] and a relatively long but blunt snout which is surpassed in length by the lower jaw.[8] Yellow perch have many fine teeth.[4] Their bodies are rough to the touch because of their ctenoid scales.[7] Like most perches, the yellow perch has two separate dorsal fins.[8] The anterior, or first, dorsal fin contains 12–14 spines while the second has 2–3 spines in its anterior followed by 12–13 soft rays. The anal fin has 2 spines and 7–8 soft rays.[7] The opercula tips are spined, and the anal fin has two spines.[4] The pelvic fins are close together, and the homocercal caudal fin is forked. Seven or eight branchiostegal rays are seen.[4]

The upper part of the head and body varies in colour from bright green through to olive or golden brown.[8] The colour on the upper body extends onto the flanks where it creates a pattern of 6–8 vertical bars over a background of yellow or yellowish green.[8] They normally show a blackish blotch on the membrane of the first dorsal fin between the rearmost 3 or 4 spines.[7] The colour of the dorsal and caudal fins vary from yellow to green while the anal and pelvic fins may be yellow through to silvery white;[8] in spawning season, males develop pronounced red or yellow color on their lower fins.[7] The pectoral fins are transparent and amber in colour. The ventral part of the body is white[8] or yellow.[9] The juvenile fish are paler and can have an almost whitish background colour.[7] The maximum recorded total length is 50 centimetres (20 in)—although they are more commonly around 19.1 centimetres (7.5 in)—and the maximum published weight is 1.9 kilograms (4.2 lb).[3]

Distribution

Yellow perch are native to the tributaries of the Atlantic Oceans and Hudson Bay in North America, particularly the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence River and Mississippi River basins. In Canada, its native range extends throughout Nova Scotia and Quebec north to the Mackenzie River. It also is common in the northwest to Great Slave Lake and west into Alberta.[4]: 4 In the United States, the native range extends south into Ohio and Illinois, and throughout most of the northeastern United States. Native distribution was driven by postglacial melt from the Mississippi River.[4]: 3–4 It is also considered native to the Atlantic Slope basin, extending south to the Savannah River. There is also a small, likely native population in the Dead Lakes region of the Apalachicola River system in Florida.[10][11]

The yellow perch has also been widely introduced for sport and commercial fishing purposes. It has also been introduced to establish a forage base for bass and walleye. These introductions were predominantly performed by the U.S. Fish Commission in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[4]: 4 However, unauthorized introductions have likely occurred from illegal introductions, dispersal through connected waterways, and use as live bait.[4]: 5–6 The current native and introduced range in the United States is through northern Missouri to western Pennsylvania to South Carolina and north to Maine, with introduced populations in the northwest and southwest portions of the United States.[12] It has been extirpated in Arkansas.[12] Introductions in Canada have been less intense than in the United States. It was primarily limited to the lakes in the Peace River drainage of British Columbia, but has currently expanded to other bordering areas since.[4] A population in Swan Lake of the Peace River drainage, however, may be indigenous.[4]: 4 The yellow perch has been introduced to China and Japan.[13]

Habitat

Yellow perch are commonly found in the littoral zones of both large and small lakes, but also inhabit slow-moving rivers and streams, brackish waters, and ponds. Due to human intervention, they are currently found in many man-made lakes, reservoirs, and river impoundments. The perch are most abundant in lakes that may be warm or cool and are extremely productive in smaller lakes where they can dominate unless controlled by predation.[4]

Biology

Yellow perch typically reach sexual maturity in 2–3 years for males and 3–4 years for females. They are iteroparous, spawning annually in the spring when water temperatures are between 2.0 and 18.6 °C (35.6 and 65.5 °F). Spawning is communal and typically occurs at night. Yellow perch are oviparous, as eggs are fertilized externally. Eggs are laid in a gelatinous strand (commonly 10,000–40,000), a characteristic unique among North American freshwater fishes. Egg strands are commonly draped over weeds, the branches of submerged trees or shrubs, or some other structure. Eggs hatch in 11–27 days, depending on temperature and other abiotic factors.[14] They are commonly found in the littoral zones of both large and small lakes, but they also inhabit slow-moving rivers and streams, brackish waters, and ponds. Yellow perch commonly reside in shallow water, but are occasionally found deeper than 15 m (49 ft) or on the bottom.[4]

In the northern waters, perch tend to live longer and grow at a slower rate. Females in general are larger, grow faster, live longer, and mature in 3–4 years compared to males, which mature in 2–3 years at a smaller size. Most research has showed the maximum age to be about 9–10 years, with a few living past 11 years. The preferred temperature range for the yellow perch is 17 to 25 °C (63 to 77 °F), with an optimum range of 21 to 24 °C (70 to 75 °F) and a lethal limit in upwards of 33 °C (91 °F) and a stress limit over 26 °C (79 °F). Yellow perch spawn once a year in spring using large schools and shallow areas of a lake or low-current tributary streams. They do not build a redd or nest. Spawning typically takes place at night or in the early morning. Females have the potential to spawn up to eight times in their lifetimes.[4]

A small aquaculture industry in the US Midwest contributes about 90,800 kg (200,200 lb) of yellow perch annually, but the aquaculture is not expanding rapidly.[4] The yellow perch is absolutely crucial to the survival of the walleye and largemouth bass in its range.[4] Cormorants feed heavily on yellow perch in early spring, but over the entire season, only 10% of their diet is perch.[15]

According to VanDeValk et al. (2002), "Cormorant consumption of adult yellow perch was similar to angler harvest, but cormorants consumed almost 10 times more age‐2 yellow perch and only cormorants harvested age‐1 yellow perch. Cormorants and anglers combined harvested 40% of age‐1 and age‐2 yellow perch and 25% of the adult yellow perch population. Total annual mortality of adult percids has not changed since cormorant colonization. Although cormorant consumption of adult percids has little effect on harvest by anglers, consumption of subadults will reduce future angler harvest of yellow perch and, to a lesser extent, walleyes."[16]

Life history

_(12679570685).jpg.webp)

Yellow perch spawn once a year in spring using large schools and shallow areas of a lake or low-current tributary streams. They do not build a redd or nest. Females have the potential to spawn up to eight times in their lifetimes. Two to five males go to the spawning grounds first and are with the female throughout the spawning process. The female deposits her egg mass, and then at least two males release their milt over the eggs, with the total process taking about five seconds. The males stay with the eggs for a short time, but the females leave immediately. No parental care is provided for the eggs or fry. The average clutch size is 23,000 eggs, but can range from 2,000 to 90,000. The egg mass is jelly-like, semibuoyant, and can reach up to 2 m long. The egg mass attaches to some vegetation, while the rest flows with the water current. Other substrate includes sand, gravel, rubble, and submerged trees and brush in wetland habitat. Yellow perch eggs are thought to contain a chemical in the jelly-like sheath that protects the eggs and makes them undesirable since they are rarely ever eaten by other fish. The eggs usually hatch in 8–10 days, but can take up to 21 days depending on temperature and proper spawning habitat. Yellow perch do not travel far during the year, but move into deeper water during winter and return to shallow water in spring to spawn. Spawning occurs in the spring when water temperatures are between 6.7 and 12.8 °C. Growth of fry is initiated at 6–10 °C, but is inactive below 5.3 °C. Larval yellow perch survival is based on a variety of factors, such as wind speed, turbidity, food availability, and food composition. Immediately after hatching, yellow perch head for the pelagic shores to school and are typically 5 mm long at this point. This pelagic phase is usually 30–40 days long.[4]

Sexual dimorphism is known to occur in the northern waters where females are often larger, grow faster, live longer, and mature in 3–4 years. Males mature in 2–3 years at a smaller size. Perch do not grow as large in the northern waters, but tend to live longer. Maximum age estimates vary widely. The age of the perch is highly based on the condition of the lake. Most research has shown the maximum age to be approximately 9–10 years, with a few living past 11 years. Yellow perch have been proven to grow the best in lakes where they are piscivorous due to the lack of predators. Perch do not perform well in cold, deep, oligotrophic lakes. Seasonal movements tend to follow the 20 °C isotherm and water temperature is the most important factor influencing fish distribution. Yellow perch commonly reside in shallow water, but are occasionally found deeper than 15 m or on the bottom. Their optimum temperature range is 21–24 °C, but have been known to adapt to warmer or cooler habitats. The common lethal limit is 26.5 °C, but some research has shown it to be upwards of 33 °C with a stress limit at anything over 26 °C. To grow properly, yellow perch prefer a pH of 7 to 8. The tolerable pH ranges have been found to be about 3.9 to 9.5. They also may survive in brackish and saline waters, as well as water with low dissolved oxygen levels.[4]

Ecology

Primarily, age and body size determine the diets of yellow perch. Zooplankton is the primary food source for young and larval perch. By age one, they shift to macroinvertebrates, such as midges and mosquitos. Large adult perch feed on invertebrates, fish eggs, crayfish, mysid shrimp, and juvenile fish. They have been known to be predominantly piscivorous and even cannibalistic in some cases. About 20% of the diet of a yellow perch over 32 g (1.1 oz) in weight consists of small fish. Maximum feeding occurs just before dark, with typical consumption averaging 1.4% of their body weight.[4]

Their microhabitat is usually along the shore among reeds and aquatic weeds, docks, and other structures. They are most dense within aquatic vegetation, since they naturally school, but also prefer small, weed-filled water bodies with muck, gravel, or sand bottoms. They are less abundant in deep and clear open water or unproductive lakes. Within rivers, they only frequent pools, slack water, and moderately vegetated habitat. They frequent inshore surface waters during the summer. Almost every cool- to warm-water predatory fish species, such as northern pike, muskellunge, bass, sunfish, crappie, walleye, trout, and even other yellow perch, are predators of the yellow perch. They are the primary prey for walleye Sander vitreus, and they consume 58% of the age zero and 47% of the age one yellow perch in northern lakes. However, in shallow natural lakes, largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides may be most influential in structuring the quality of yellow perch populations. In Nebraska's Sandhill lakes, the mean weight and quality of yellow perch is not related to invertebrate abundance, but is related to the abundance of largemouth bass. The three primary factors influencing quality panfish populations are predators, prey, and the environment.[17]

In eastern North America, yellow perch are an extremely important food source for birds such as double-crested cormorants. The cormorants specifically target yellow perch as primary prey. Other birds also prey on them, such as eagles, herring gulls, hawks, diving ducks, kingfishers, herons, mergansers, loons, and white pelicans. High estimates show that cormorants were capable of consuming 29% of the age-three perch population.[18] Yellow perch are effective at escaping predation seasonally by lake trout and other native fishes during summer, perhaps due to the high thermal tolerance of yellow perch.[4]: 19

Perch are commonly active during the day and inactive at night except during spawning, when they are active both day and night. Perch are most often found in schools. Their vision is necessary for schooling and the schools break up at dusk and reform at dawn. The schools typically contain 50 to 200 fish, and are arranged by age and size in a spindle shape. Younger perch tend to school more than older and larger fish, which occasionally travel alone, and males and females often form separate schools. Some perch are migratory, but only in a short and local form. They also have been observed leading a semianadromous life. Yellow perch do not accelerate quickly and are relatively poor swimmers. The fastest recorded speed for a school was 54 cm/s (12.08 mph), with individual fish swimming at less than half that speed.[4]

Some examples of parasites and diseases that afflict yellow perch include the epizootic bacterium Flavobacterium columnare,[19] red worm Eustrongylides tubifex,[4]: 14–15 cnidarians of subphylum Myxozoa[20]: 760 [21] including brain parasite Myxobolus neurophilus,[19][22] broad tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum,[20]: 760 and parasitic copepods Ergasilus spp.[4]: 14–15

Current management

Managers employed management techniques at Drummond Island, Michigan, such as harassing the cormorants and killing them as needed. Overall, the harassment deterred 90% of cormorant foraging attempts, while killing less than 6% on average at each site; yellow perch abundance increased significantly due to their being the predominant prey of cormorants by total number and weight at that lake.[23] Lakes in South Dakota without suitable spawning substrate have had conifers introduced, such as short-needle spruce, to increase both spawning habitat and hatching success. Managers have identified seven key unauthorized pathways for the introduction of the yellow perch to non-native regions: shipping, recreational and commercial boating, construction of new canals and water diversions, releases from live food fish markets, releases from the aquarium and water garden trade, use of live bait, and illegal introductions to create new fisheries. The most likely unofficial pathways are illegal introductions, dispersal through connected waterways, and live bait. Many authorized introductions by natural resources agencies have taken place, as well, due to the sport-fishing demand.[4]

In 2000, the parasite Heterosporis spp. was discovered in yellow perch on the Eagle River Chain of Lakes in Vilas County in Wisconsin, and has since been found in Minnesota, Michigan, and Ontario. The parasite does not infect people, but can infect many important sport and forage fish including the yellow perch. It does not kill the infected fish, but the flesh of a severely infected fish becomes inedible when the fish dies and the spores are then spread through the water to infect another fish. That concerns commercial fisherman in the Great Lakes regions that depend on these fish. The infected perch are not marketable. The current infection rates are 5% of harvest. Viral hemorrhagic septicemia is another serious disease in perch in the Great Lakes region. It has already killed thousands of drum in Lake Ontario and caused a large die-off of yellow perch in Lake Erie in 2006. Ontario is restricting commercial bait licenses as a precaution against this disease. Outside its native range, very few diseases or parasites have been found.[4]

Fishing

.jpg.webp)

Yellow perch are a popular sport fish, prized by both recreational anglers and commercial fishermen for their delicious, mild flavor. Because yellow perch are among the finest flavored pan fish, they are occasionally misrepresented on menus within the restaurant industry. White perch, rock bass, and many species of sunfish (genus Lepomis) are sometimes referred to as "perch" on menus. The voracious feeding habits of yellow perch make them fairly easy to catch when schools are located, and they are frequently caught by recreational anglers targeting other species. Perch at times attack lures normally used for bass such a 3" tubes, Rapala minnows, and larger curl tail grubs on jigheads, and small, brightly colored casting spoons, but the simplest way to catch them is to use light line, 4 to 8# test and light, unpainted jig heads, 1/32–1/16 oz. Too many small soft plastic lure designs to mention can catch all panfish, but minnow-shaped lures with a quivering tail work much of the time, so long as the retrieval speed is slow and the lure is fished at the depth the perch are swimming. Thin, straight-tail grubs require the slowest speed of retrieval and are preferred when the bite is slow, which is much of the time.

Some good baits for perch include worms, live and dead minnows, small freshwater clams, crickets, and any small lure resembling any of these. Larger perch are often caught on large live minnow on a jighead, especially when fished over weed beds. Bobbers, if used, should be spindle type for the least resistance when the bait is struck, but small, round bobbers work well, too, yet indicate any slight pull of the bait. Raising the rod tip is usually more than enough force to set the hook.

Some yellow perch fisheries have been affected by intense harvesting, and commercial and recreational harvest rates often are regulated by management agencies. In most aquatic systems, yellow perch are an important prey source for larger, piscivorous species, and many fishing lures are designed to resemble yellow perch.

Aquaculture

.jpg.webp)

Yellow perch is a viable species for aquaculture. This species has shown a net weight gain between 37 and 78 grams over a three-year period in a study that raised yellow perch in outdoor ponds.[24] Yellow perch meet several characteristics that make a species fit for aquaculture. Some such characteristics are as follows: they are low on the food chain, needing an optimal protein content of 21-27%, are accepting of pelleted fish feed, grow well in high densities due to their schooling nature, and the fish do not turn cannibalistic at high densities.[25] When grown in ponds or tanks, yellow perch do not exhibit off flavors compared to wild caught yellow perch. These fish become sexually mature before they reach market size under natural conditions. Yellow perch rely on environmental cues, such as cooler temperatures, to mature. Controlling the temperature of the system allows yellow perch to be grown to market size before they mature.[25][26][27]

Market

.JPG.webp)

For over 100 years, Canada and the United States have been commercially harvesting yellow perch in the Great Lakes with trapnets, gillnets, and poundnets. In Canada, the estimated catch in 2002 was 3,622 tons with a value of $16.7 million, second only to walleye at $28.2 million.[4]: 15 The greatest demand in the United States is in the north-central region, where nearly 70% of all yellow perch sales in the US occur within 80 km (49.7 mi) of the Great Lakes.[4]: 16 Yellow perch is one of the easiest fish to catch, and can be taken in all seasons, and tastes great. Therefore, it is a desirable sport fish in some locations within the US and Canada. It even makes up around 85% of the sport fish caught in Lake Michigan.[4]: 16

The market demand for wild yellow perch has decreased due to overfishing in the 1960s and 1970s but farmed perch has become more popular. Farmed yellow perch reduce the need for mass harvesting from bodies of water. In 2000 farmed perch on the domestic and international markets were often the same or similar quality to wild perch.[26]

Etymology

According to Brown, Runciman, Bradford and Pollard (2009), the genus name, Perca, is derived from ancient Greek for "perch" and the specific epithet, flavescens, is Latin for "becoming gold" or "yellow colored".[4]: 2 Perca may also mean "dusky".[20]: 761 [28]

References

- NatureServe (2013). "Perca flavescens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T202567A18235054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T202567A18235054.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Perca flavescens Yellow Perch". NatureServe. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2019). "Perca flavescens" in FishBase. December 2019 version.

- Brown, T. G.; Runciman, B.; Bradford, M. J.; Pollard, S. (2009). "A biological synopsis of yellow perch Perca flavescens" (PDF). Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2883: i–v, 1–28. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Perch, yellow (Perca flavescens)". International Game Fish Association. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Sutton, Keith "Catfish" (15 March 2018). "Oldest Fishing Record". Water Gremlin. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Creque, Sara (2000). Fink, William (ed.). "Perca flavescens American perch". Animal Diversity Web. Regents of the University of Michigan. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens)". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Government of Canada. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Maryland Fish Facts: Yellow Perch". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Yellow Perch". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Bisping, Scott M.; Alfermann, Ted J.; Strickland, Patrick A. (2019). "Population Characteristics of Yellow Perch in Dead Lake, Florida". Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management. 10 (2): 296–303. doi:10.3996/082018-JFWM-068.

- Fuller, Pam; Neilson, Matt (15 August 2019). "Perca flavescens (Mitchill, 1814)". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. USGS. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Mellage, Adrian (30 March 2015). "Perca flavescens (yellow perch)". CABI Compendium. Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. doi:10.1079/cabicompendium.70036.

- Paukert, Craig P.; Willis, David W.; Klammer, Joel A. (2002). "Effects of predation and environment on quality of yellow perch and bluegill populations in Nebraska sandhill lakes". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 22 (1): 86–95. doi:10.1577/1548-8675(2002)022<0086:eopaeo>2.0.co;2. S2CID 14232024.

- Belyea, G. Y.; Maruca, S. L.; Diana, J. S.; Schneeberger, P. J.; Scott, S. J.; Clark, R. D., Jr; Ludwig, J. P.; Summer, C. L. (1999). Impact of double-crested cormorant predation on the yellow perch population in the Les Cheneaux Islands of Michigan (Report). US Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. pp. 47–60.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - VanDeValk, A. J.; Adams, C. M.; Rudstam, L. G.; Forney, J. L.; Brooking, T. E.; Gerken, M. A.; Young, B. P.; Hooper, J. T. (2002). "Comparison of angler and cormorant harvest of walleye and yellow perch in Oneida Lake, New York". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 131 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(2002)131<0027:coaach>2.0.co;2.

- Paukert, Craig P.; Willis, David W.; Klammer, Joel A. (2002). "Effects of predation and environment on quality of yellow perch and bluegill populations in Nebraska sandhill lakes". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 22 (1): 86–95. doi:10.1577/1548-8675(2002)022<0086:EOPAEO>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 14232024.

- Burnett, John A.D.; Ringler, Neil H.; Lantry, Brian F.; Johnson, James H. (2002). "Double-crested cormorant predation on yellow perch in the eastern basin of Lake Ontario". Journal of Great Lakes Research. 28 (2): 202–211. doi:10.1016/S0380-1330(02)70577-7.

- Scott, Steven J.; Bollinger, Trent K. (2014). "Flavobacterium columnare: an important contributing factor to fish die-offs in southern lakes of Saskatchewan, Canada". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 26 (6): 832–836. doi:10.1177/1040638714553591. PMID 25274742.

- Scott, W.B.; Crossman, E.J. (1973). Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Ottawa: Fisheries Research Board of Canada. pp. 755–761. Bulletin 184. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Cone, D.K. (1994). "Annual cycle of Henneguya doori (Myxosporea) parasitizing yellow perch (Perca flavescens)". The Journal of Parasitology. 80 (6): 900–904. doi:10.2307/3283438. JSTOR 3283438. PMID 7799162.

- Scott, S.J.; Griffin, M.J.; Quiniou, S.; Khoo, L.; Bollinger, T.K. (2014). "Myxobolus neurophilus Guilford 1963 (Myxosporea: Myxobolidae): a common parasite infecting yellow perch Perca flavescens (Mitchell, 1814) in Saskatchewan, Canada". Journal of Fish Diseases. 38 (4): 355–364. doi:10.1111/jfd.12242. PMID 24617301.

- Brian, S. Dorr; Moerke, Ashley; Bur, Michael; Bassett, Chuck; Aderman, Tony; Traynor, Dan; Singleton, Russell D.; Butchko, Peter H.; Taylor, Jimmy D. II (2010-06-01). "Evaluation of harassment of migrating double-crested cormorants to limit depredation on selected sport fisheries in Michigan". Journal of Great Lakes Research. 36 (2): 215–223. doi:10.1016/j.jglr.2010.02.001. ISSN 0380-1330. S2CID 41736987.

- Malison, Jeffrey; Held, James (2008). "Farm-based Production Parameters and Breakeven Costs for Yellow Perch Grow-out in Ponds in Southern Wisconsin".

- Weldon, Vanessa (26 August 2019). Tiu, Laura; Weeks, Chris (eds.). "Yellow Perch Aquaculture". Freshwater Aquaculture. National Cooperative Extension. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Manci, Bill (December 2000). "Prospects for Yellow Perch Aquaculture" (PDF). The Advocate. Global Aquaculture Alliance. pp. 62–63. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Hart, Steven D.; Garling, Donald L.; Malison, Jeffrey A., eds. (October 2006). "Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) Culture Guide" (PDF). North Central Regional Aquaculture Center. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Ladwig, Christopher. "Perch Dissection". Vandenberg Middle School. Retrieved 22 November 2022.