Personal life of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

The personal life of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk has been the subject of numerous studies. Atatürk founded the Republic of Turkey and served as its president from 1923 until his death on 10 November 1938. According to Turkish historian Kemal H. Karpat, Atatürk's recent bibliography included 7,010 different sources.[1] Atatürk's personal life has its controversies, ranging from where he was born to his correct full name. The details of his marriage have always been a subject of debate. His religious beliefs were discussed in Turkish political life as recently as the Republic Protests during the 2007 presidential election.

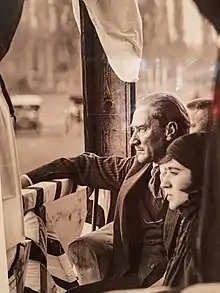

Atatürk and his adopted daughter Rukiye Erkin, 1926 | |

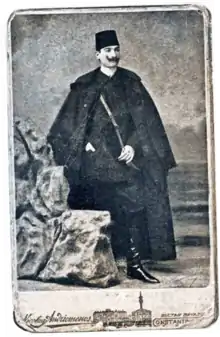

| Born | Ali Rıza oğlu Mustafa (Mustafa son of Ali Rıza) 1881 Salonica (Thessaloniki), Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 10 November 1938 (aged 56–57) Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Resting place | Anıtkabir, Ankara, Turkey |

| Nationality | Turkish |

| Alma mater | Ottoman War Academy Imperial Military Staff College |

| Known for | Military commander, revolutionary statesman |

| Spouse | Latife Uşaklıgil (1923–25) |

| Partner | Fikriye Hanım |

| Children | 11 (adopted) |

| Parent(s) | Ali Rıza Efendi Zübeyde Hanım Ragıp Bey (step father) |

| Family | Makbule Atadan (sister) Naciye (sister) |

| Signature | |

| |

Mustafa Kemal's personality has been an important subject both for scholars and the general public.[1] Much of substantial personal information about him comes from memoirs by his associates, who were at times his rivals, and friends. Some credible information originates from Ali Fuat Cebesoy, Kâzım Karabekir, Halide Edib Adıvar, Kılıç Ali, Falih Rıfkı Atay, Afet İnan, there is also secondary analysis by Patrick Balfour, the 3rd Baron Kinross, Andrew Mango and, most recently, Vamık D. Volkan and Norman Itzkowitz.

Name

In Turkish tradition, names have additional honorary or memorial values besides their grammatical identification function. It is possible to translate a name from Turkish to other languages, but care should be given as names' form varies from one language to another. Atatürk had Mustafa as his name at birth. Mustafa (Arabic: مصطفى – Muṣṭafā, "the chosen one"), an epithet of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, was a common name at that time. Young Mustafa studied at Salonica Military School, the military junior high school in Salonica (now Thessaloniki in modern Greece), where his mathematics teacher Captain Üsküplü Mustafa Sabri Bey gave him the additional name "Kemal" ("perfection") because of his student's academic excellence.[2]

On 27 November 1911, Mustafa Kemal was promoted to the rank of Binbaşı, an Ottoman military rank denoting the commander of "a thousand soldiers," equivalent to the rank of Major in the modern Turkish army. Since, in Ottoman military ranks, "Bey" was a common title given to all ranks for Binbaşı and above, Mustafa Kemal Efendi, henceforth, was addressed as "Mustafa Kemal Bey". On 1 April 1916, Mustafa Kemal was promoted to the rank of Mirliva, equivalent to Major General today. In Ottoman military ranks, Pasha was a common title given to all ranks at and above Mirliva, and he was from then on addressed as "Mustafa Kemal Pasha" (Turkish: Paşa).

Kemal Pasha, disgusted by the capitulations and concessions made by the Sultan to the Allies, and by the occupation of Constantinople (known as Istanbul in English since 1930) by the British, resigned from his post on 8 July 1919. He escaped from Istanbul by sea, passing through British Royal Navy patrols and landing on the Black Sea port city of Samsun, to organize the resistance against the Allied Powers' occupation of Anatolia. After his resignation, the Sublime Porte, the Ottoman imperial government, issued a warrant and later condemned him to death in absentia.[3]

On 19 September 1921, the Turkish Grand National Assembly presented him with the title of Gazi, which denotes, a combat or wounded veteran, with the religious connotation of defeating non-Islamic forces, and bestowed upon him the rank of Marshal for his achievements during the War of Independence. Henceforth, he'd be addressed as "Gazi Mustafa Kemal".[4]

On 21 June 1934, the Grand National Assembly recognized the need for registration and use of fixed hereditary surnames. The Surname Law was proposed and later put into force. On 24 November 1934, the Assembly enacted a special law to bestow on Mustafa Kemal the surname "Atatürk," which translates as "Father of the Turks,"[5][6] and established "Atatürk" as a unique surname.[note 1]

List of names and titles

- Birth: Ali Rıza oğlu Mustafa

- 1890s: Mustafa Kemal

- 1911: Mustafa Kemal Bey

- 1916: Mustafa Kemal Paşa

- 1921: Gazi Mustafa Kemal Paşa

- 1934: Kemal Atatürk

- 1935: Kamâl Atatürk

- 1937: Kemal Atatürk[7]

Time magazine says: "Man of Seven Names. This blond, blue-eyed, Bacchic roughneck had seven names before he died as Kamâl Atatürk."[8] However, Atatürk returned to the old spelling of Kemal from May 1937 and onwards.[7]

Birth date

Due to differences between calendars of the period, Atatürk's precise birth date is not known. The Ottoman Empire recognized the Hijri calendar and the Rumi calendar. The Hijri was an Islamic calendar, used to mark the religious holidays. It was lunar, with years of 354 or 355 days. The Rumi was a civil calendar, adopted in 1839. It was solar, based on the Julian Calendar. Both counted time from the Hijra, the migration of Muhammad to Medina. Between the two calendars significant differences in elapsed time were present. Various reforms were made to reconcile them but typically there was always a difference.

Atatürk's birth date was recorded in the public records of Turkish Selanik as Anno Hegirae 1296 with no sign whether this was based on the Rumi or on the Hijri calendar. In view of this confusion Atatürk set his own birthday to coincide with the Turkish Independence Day, which he announced was 19 May 1919, the day of his arrival in Samsun, in a speech given in 1927. His identification with Independence Day implied his selection of the civil calendar, in which AH 1296 lasts from 13 March 1880 to 12 March 1881. The latter dates are in the Gregorian Calendar just adopted for the Republic by Atatürk for purposes of standardization (the Julian Calendar was rejected earlier). Atatürk therefore listed his own birthday in all documents official and unofficial as 19 May 1881.[9]

Atatürk was told by his mother that he was born on a spring day, but his younger sister Makbule Atadan was told by others that he was born at night during a thunderstorm. Faik Reşit Unat received differing responses from Zübeyde Hanım's neighbors at Salonika. Some claimed that he was born on a spring day, but others stated on a winter day during either January or February. A date that has gained some acceptance is 19 May, a date which originated with the historian Reşit Saffet Atabinen. 19 May is the symbolic start of the Turkish Independence War, and Atabinen linked Atatürk's birth day to the start of the Independence War – a gesture which Atatürk appreciated. There was even a plan to establish a "Gazi" day. Another story about this date is that a teacher asked Atatürk his birth date, that he responded he did not know it, and that the teacher suggested 19 May. Then again, there are two ways to interpret this; the "Gregorian 19 May 1881" would imply Rumi 1 March 1297, which conflicts with the only recorded information, Rumi 1296. It is also possible to say "Rumi 19 May 1296", which implies a date in the Gregorian year 1880.

Some sources ignore the day and month altogether, and print his birth date as Gregorian 1880/81. Other claims are:

- Enver Behnan Şapolyo claimed that Atatürk was born on Gregorian 23 December 1880.

- Şevket Süreyya Aydemir claimed that he was born on Gregorian 4 January 1881.

- Muhtar Kumral, former head of the Mustafa Kemal Association, claimed that he was born on Gregorian 13 March 1881, and stated they used Makbule Atadan. A conversion from Gregorian to Rumi sets the day in Rumi to 1 March 1297. The validity of this claim is questionable, since the written record states Rumi 1296, not 1297.[10]

- Tevfik Rüştü Aras claimed that Atatürk was born between 10 May and 20 May. He stated that this information was shared with Atatürk, and that Atatürk responded "Why not May 19."

Atatürk's last official identity document (Turkish: nüfus cüzdanı) does not include the day and month, but the year 1881 is visible.[10] It is exhibited in the Atatürk Museum in Şişli.[10] The Republic of Turkey announced 19 May 1881 officially to the public and diplomatically to other countries as his accepted birthday.[10]

Nationality

The Ottoman Empire was not a national state and the records were not kept based on nationality, but on religion. The rise of nationalism in Europe had extended to the Ottoman Empire during the 19th century and the Millet system began to degrade. Atatürk's parents and relatives used Turkish as their native language and were part of the Muslim millet.[11] His father Ali Rıza Efendi is thought by some to have been of Albanian or Slavic origin;[12][13][14][15][16] however, according to Falih Rıfkı Atay, Vamık D. Volkan and Norman Itzkowitz, Ali Rıza's ancestors were Turks, ultimately descending from Söke in the Aydın Province.[17][18] His mother Zübeyde is thought to have been of Turkish origin[14][15] and according to Şevket Süreyya Aydemir, she was of Yörük ancestry.[19] There are also some suggestions about his partial Slavic origin.[20][21][22]

Early life

Atatürk was born during the Belle Époque of European civilization. Russia was implementing reforms; Japan opened its doors to the West during the Meiji Restoration. The Ottoman Empire was going through transformation. Ottoman military reform efforts, like the contemporaneous Modernization of Japanese Military 1868–1931, managed to develop a modern army. Racial, regional, ethnic and national stereotypes were part of discourse throughout the world. Ottoman people were not immune to these developments and there was a rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire.

Preparatory school

Ali Rıza Bey's desire was to send Atatürk to the newly opened Şemsi Efendi School, which had a contemporary education program. Zübeyde Hanım wanted him to attend a traditional school. The traditional Muslim schools had programs based on mostly prayers and hymns. This caused arguments within the family. He first enrolled in a traditional religious school. He later switched to Şemsi Efendi School.

In 1888, Ali Rıza Efendi died at an age of 47. Atatürk was 7 years old. Zübeyde Hanım was 31. Zübeyde Hanım and her two children lived with her brother Hüseyin for a period. Hüseyin was the manager of a farm outside Salonika. Mustafa worked on the farm.

Zübeyde Hanım married Ragıp Bey. Ragıp Bey was also a widower with four children. Atatürk liked Süreyya. His other step brother was employed by Regie Company. Because he was not the senior male in the house after his mother's marriage, Atatürk left the house and lived with a relative.

Military education

Atatürk wanted to attend the military school. As a young boy, he admired the Western-style uniforms of the military officers. He enrolled to the military junior high school Turkish: Selânik Askerî Rüştiyesi in Selânik. In 1896, he enrolled in the Monastir Military High School. Monastir is today's Bitola, in the North Macedonia. Both of these regions saw discontent and revolts towards the Ottoman administration.

On 13 March 1899, he enrolled in the Ottoman War Academy in Constantinople (Turkish: Mekteb-i Harbiye-i Şahane). It was a boarding school with dormitories within its premises. The military school was strictly controlled by Abdul Hamid II. Newspapers were not allowed in the school, and textbooks were the only accepted books. The school not only taught military skills but also religious practices and social work. The curriculum at this school demanded either donating money or working for charity. He graduated from the Ottoman War Academy in 1902.

On 10 February 1902, he enrolled in the Imperial Military Staff College in Constantinople, from which he graduated on 11 January 1905. There were two officer tracks in the Ottoman imperial army. One of them was the officers "educated within the army itself", Alaylı, and the other consisted of officers trained in modern military schools, Mektepli. He was a "school trained" officer. School educated officers had a strong ideological imprint toward family and country, and he had shown tendencies toward both. When he joined the Ottoman Army, he had already passed 13 years of military education.

Private life

Family

Zübeyde Hanım's first child was Fatma, then Ömer, later Ahmet was born. They all died in early childhood. Mustafa was the fourth child. Makbule followed him in 1885. Their sister Naciye was born in 1889. Naciye was lost to childhood tuberculosis.

Ragıp Bey had four children from his first marriage. His first child, Süreyya died during World War One. Ragıp Bey had a brother Colonel Hüsamettin. He and Vasfiye Hanım had a daughter named Fikriye (1897 – 31 May 1924).[23] Of the 9 siblings, five sharing at least one parent, only his biological sister, Makbule (1885–1956), survived him.

| Hacı Abdullah Ağa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| İbrahim Ağa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Güzel Ayşe Hanım | Feyzullah Ağa | ? | Hafız Ahmet Efendi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hüsamettin | Hüseyin Efendi | Hasan Efendi | Mehmet Emin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ragıp Bey | Zübeyde Hanım | Ali Rıza Efendi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fikriye | Step 1 | Fatma | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Süreyya | Ömer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hasan | Ahmet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Step 2 | Mustafa | Latife | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Makbule | Abdurrahim (p) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naciye | Sabiha (a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rukiye (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zehra (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Afet (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fikriye (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ülkü (a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebile | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wife

.jpg.webp)

Atatürk married only once, to Latife Uşaklıgil (or Uşşaki); a multilingual, and self-confident woman who was educated in Europe and came from an established, ship-owning family from Smyrna (now Izmir).[24]

Atatürk met Latife during the recapture of occupied Smyrna on 8 September 1922. Atatürk was invited to Uşaklıgil residence during his stay in Smyrna. He had chance to observe Latife closely. Their initial acquaintanceship period lasted a relatively short time as he had to return to Angora (now Ankara) on 2 October. Atatürk opened up his interest to Latife by asking her "Don't go anywhere. Wait for me." On 29 January 1923, he arranged for the permission to marry from her family, with the assistance of the chief of staff Fevzi Çakmak. Kâzım Karabekir was present at their wedding. These were not random decisions.

In Turkish culture, the groom asks his family or respected people, with whom he has close relationships, to perform this act. Latife did not cover her face during the wedding, though during this period it was the tradition for brides to do so. They did not have a honeymoon just after the wedding. The elections for the parliament were coming. He received the representatives of local newspapers next day of his wedding. He prepared for his public speech on 2 February. The honeymoon, an Anatolian tour, was a chance to show his wife's unveiled face as a role model for modern Turkish women. "It's not just a honeymoon, it's a lesson in reform," one observer remarked.[25]

As a First Lady, she was part of the women's emancipation movement, which started in Turkey in the early 1920s. Latife showed her face to the world with a defiance that shocked and delighted onlookers.[25] She did not wear a hijab but covered her head with a headscarf (Turkish: Başörtüsü). She urged Turkish women to do the same and lobbied for women's suffrage.[26] Atatürk passed the law giving women the right to vote after he was elected.

Latife insisted on accompanying him to the eastern towns even though the wives of other officials stopped at Samsun and did not travel further to the devastated east. The attention of Atatürk was directed to conventional gatherings. The balance was hard to establish. At Erzurum, Latife and Atatürk reached a breaking point. They had a public quarrel. Atatürk asked Latife to go to Angora, with his trusted ADC Salih Bozok. They were divorced on 5 August 1925. The circumstances of their divorce remain publicly unknown. A 25-year-old court order banned the publishing of his former wife's diaries and letters, which might have contained information on the matter. The Turkish History Foundation kept the letters since 1975. Upon expiration of the court order, the Turkish History Foundation said that Latife Uşaklıgil's family demanded that the letters were not to be disclosed.[27]

Children

One of his quotes was "Children are a new beginning of tomorrow." He established 23 April as "Children's Day" and 19 May as "Youth and Sports Day". Children's Day commemorates the opening of Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1920. The designation of Children's Day came in 1929 upon the recommendation of the Institution of Children's Protection. Both days are celebrated today. Youth and Sports Day is a national holiday in Turkey.

He had no biological children from his marriage but had eight adopted daughters and one son. The names of his children were Zehra Aylin, Sabiha (Gökçen), Rukiye (Erkin), Afet (İnan), Nebile (Bayyurt), Afife, Fikriye, Ülkü (Doğançay, later Adatepe), and Mustafa. Additionally, he had two children under his protection, Abdurrahim Tuncak and İhsan.[28]

In 1916, Atatürk took Abdurrahim, aged eight, under his protection. There is a photograph showing Atatürk with his uniform during his assignment in Diyarbakir accompanied with the early teenage Abdurrahim. Abdurrahim was entrusted to Zübeyde Hanim's care. He did not remember his biological parents. This brought questions if he was left an orphan during the Caucasus Campaign. Abdurrahim stated his earliest memories belong to the Zübeyde Hanim's house in Akarether. Atatürk gave the surname Tuncak to Abdurrahim.

In 1924, Zehra from Amasya and Rukiye from Konya came under his protection. Zehra fell to her death from a train near Amiens on 20 November 1935. France police inquiry concluded that it was a suicide rather than an accident. On 22 September 1925, Atatürk adopted a 12-year-old girl named Sabiha, an orphan who approached him at Bursa train station. She was sent to Russia for aviation training. On 25 October 1925, Atatürk met an 18-year-old girl, Afet (İnan). She was the daughter of a close family friend. She had lost her mother, and her father had married another woman. She was trying to make a living in Smyrna (Izmir) by teaching young girls. She lacked advanced education. Atatürk supported her advance education expenses, while she continued to support herself by teaching. Later, she became a trusted person. He asked her to copy edit his speeches, and dictate his materials. In 1935, Atatürk met a three-year-old girl, Ülkü. She was the child of a retainer of his mother and the stationmaster. She was the only daughter that stayed close to him until a few weeks before his death.

According to Atatürk:

There is one trait I have had since my childhood. In the house where I lived. I never liked to spend time with my sister or with a friend. Since my childhood I have always preferred to be alone and independent, that is how I always lived. I have another trait: I have never had any patience with any advice or admonition which my mother – my father died very early – my sister or any of my closest relatives pressed on me according to their lights. People who live with their families know that there are never short of innocent and sincere warnings from left and right. There are only two ways of dealing with them. You either ignore them or obey them. I believe neither way is right.[29]

One changing view about Atatürk is his foresightedness, foster and promotion of the leadership among Turkish revolutionaries.[30] Initial reviews depict him as an unchallenged leader, the single man. Recent studies analyze the period from the populist perspective. His leadership activities had extending effects on the political, social and cultural context of the Republic.[30] These studies gives clues on his abilities to foster the cooperation among different people, such as in the "History of National Struggle Volumes I through V".[31] His significance during independence was cited for his ability to unify people. It is pointed out that organizations in the countryside for resistance against occupation was happening effectively before his involvement. His ability to channel people did not. The foundation for the civilian participation in the government [parliament being never closed during his reign] and establishment of civic society [his insistence of keeping military out of daily politics] are cited having the roots in the Kemal's presidency, not after.[30] The failed reforms of the regional countries, after the passage of its leaders, were generally used as an example of the Atatürk's leadership among the Turkish Revolutionaries. His effect lasted many years after his passage.

Sexuality

British military intelligence reports from January 1921 authored by Charles Harington noted Atatürk's "homosexual vice".[32][33] However, British historian A. L. Macfie notes that these reports may have come from Atatürk's enemies to discredit him.[34] According to British biographers H. C. Armstrong and Patrick Balfour, and Turkish author İrfan Orga (who served under him[34]), Atatürk was bisexual.[35][36][37] Armstrong's book was the first biography of Atatürk, it was published during his lifetime and it is controversial: reviewers are divided on whether it is a realistic biography or a provocative fictional one.[38] When Turkish journalist Peyami Safa first translated it into Turkish, he self-censored the excerpts about Atatürk's sexual life due to the control over his image.[38] Allegations of homosexuality were similarly censored in all later translations, including the latest one in 2013.[38][39] The LGBT encyclopedia Queers in History, citing Balfour, mentions the same sexual orientation.[40] French LGBT historian Michel Larivière also lists Atatürk in his Dictionnaire historique des homosexuel-le-s célèbres.[41][42] In 2007, Turkish authorities protested after Atatürk was listed among famous homosexuals and bisexuals in a book about homophobia published by the Minister of Education of the French Community of Belgium and intended to teachers. The list was removed from the upcoming edition of the book.[43][44][45] The same year, a Turkish court blocked YouTube because of a video describing Atatürk as homosexual.[46][47]

Love of nature

He attached importance to his horse Sakarya and his dog Fox. He was also anecdotally linked to preservation of Turkish Angora after an article in the Turkey's Reader's Digest reportedly claimed that Atatürk said "his successor would be bitten on the ankle by an odd-eyed white cat.[48]

Atatürk established the Forest Ranch in 1925. He wanted to have a modern farm in the suburbs of the capital including a green haven (arboretum) for people.[49] The Forest Ranch developed a program to introduce domesticated livestock and horticulture in 1933. As a consequence of children being interested in the animals Atatürk involved in developing a program which then became known as "Ankara Zoo". The modern zoo which took 12 years to build, first of its kind in Turkey, gave a chance to people observe animals beyond the boundaries of circus and fairs. Atatürk, with his smallest adopted daughter Ülkü spend his time at the Forest Ranch and throughout the development stages of the Zoo until he died in 1938. The official opening was in 1945.

Lifestyle

.jpg.webp)

Throughout most of his life, Atatürk was a moderate-to-heavy drinker, often consuming half a litre of rakı a day; he also smoked tobacco, predominantly in the form of cigarettes.[50][51][52] He loved reading books, listening to music, dancing, horseback riding and swimming. He liked to play backgammon and billiards. He was interested in Zeybek dance, wrestling and Rumelian songs. In his free times, he read books about history. Instead of dealing with other issues, a politician who detested reading more than necessary told him, "Did you go to Samsun by reading a book?" Atatürk replied: "When I was a child, I was poor. When I received two pennies, I would give one penny of it to the book. If it was not so, I would not have done any of this."[53]

Atatürk told the Romanian Foreign Minister of the time, Victor Antonescu, on 20 March 1937:

Those who see the existence of all mankind in their own person are miserable. Obviously, that man will disappear as an individual. The need for any person to be satisfied and happy to live is to work not for himself but for the future. An insightful man can only act this way. Full enjoyment and happiness in life, but the honor, presence, happiness of future generations can be found.[54]

Religious beliefs

There is a controversy on Atatürk's religious beliefs.[55] Some researchers have emphasized that his discourses about religion are periodic and that his positive views related to this subject are limited in the early 1920s.[56]

Some non-Turkish researchers, as well as some Turkish ones, insist that he was a religious skeptic and an agnostic, i.e. non-doctrinaire deist,[57][58] maybe an atheist,[59][60][61] or even anti-religious and anti-Islamic in general.[62][63]

However, other researchers[64] claim that he was a devout Muslim.[65][66][67][68] Atatürk's adopted daughter Ülkü Adatepe stated that Atatürk told her he would pray to Allah before every battle.[69]

Expressing that he sees religion as a "necessary institution",[70] Atatürk used expressions such as "our religion" and "our great religion" for Islam.[71] According to governmental archives, in his two speeches in 1922 and 1923, he stated "Gentlemen, Allah is one and great."[72]

In 1933, the US ambassador Charles H. Sherrill interviewed him. According to Sherrill, in the interview he denied being an agnostic and stated that he believed there is only one creator. Also he said that he thought it was good for humanity to pray to God.[73] According to Atatürk, the Turkish people do not know what Islam really is and do not read the Quran. People are influenced by Arabic sentences that they do not understand, and because of their customs they go to mosques. When the Turks read the Quran and think about it, they will leave Islam.[74]

In his youth, he underwent religious training, though it was brief. His military training included religious imprinting. He knew the Arabic language well enough to understand and interpret the Quran. He studied the "History of Islam" by Leone Caetani and the "History of Islamic Civilisation" by Jurji Zaydan. He authored the chapter in "Islamic History" himself when he wanted history books for high schools prepared. Atatürk's religious knowledge was considerably high in its nature and level.[65]

General perception

Atatürk believed that religion is an important institution:

Religion is an important institution. A nation without religion cannot survive. Yet it is also very important to note that religion is a link between Allah and the individual believer. The brokerage of the pious cannot be permitted. Those who use religion for their own benefit are detestable. We are against such a situation and will not allow it. Those who use religion in such a manner have fooled our people; it is against just such people that we have fought and will continue to fight. Know that whatever conforms to reason, logic, and the advantages and needs of our people conforms equally to Islam. If our religion did not conform to reason and logic, it would not be the perfect religion, the final religion.[70]

However, his speeches and publications criticized using religion as a political ideology.[65] According to him, "Religions have been basis of the tyranny of kings and sultans."[75] He stated that religion should be in conformity with reason, science and logic. The problem was not religion, but how believers understood and applied religion. Atatürk expressed that religion and superstition should be separated:[64]

I want to say that the Turkish nation should be more religious, that is, they should be religious in all their simplicity. The truth is that religion does not contain anything that prevents progress. However, there is another religion among us that is more complex, artificial and consists of superstitions. If they cannot approach the light, they have lost themselves. We will save them.[64]

True religion could not be understood as long as false prophets isolated and religious knowledge is enlightened. The only way to deal with false prophets was to deal with the Turkish people's illiteracy and prejudice.[71]

Religion and the individual

.png.webp)

Religion, particularly Islam, was between an individual and God in Atatürk's eyes.[76] He believed it was possible to blend native tradition (based on Islam) and Western modernism harmoniously.[77] In this equation, he gave more emphasis towards the modernization. His modernization aimed to transform social and mental structures (native traditions of Islam) to eradicate the irrational ideas, magical superstitions and so on.[77]

Atatürk was not against religion but what he perceived as all Ottoman religious and cultural elements that brought limits to people's self being.[77] He concentrated his reforms (regarding popular sovereignty) against obstacles for the individual choices being reflected in the social life. He viewed civil law and abolition of the caliphate as required for reflection of individual choices. He perceived religion as a matter of conscience or worship, but not politics. The best response on this issue comes from himself:

Religion is a matter of conscience. One is always free to act according to the will of one's conscience. We (as a nation) are respectful of religion. It is not our intention to curtail freedom of worship, but rather to ensure that matters of religion and those of the state do not become intertwined.[78]

Atatürk believed in freedom of religion, but he was a secular thinker and his concept of freedom of religion was not limitless. He differentiated between social and personal practice of religion. He applied social considerations (secular requirements) when the public practice of religion was considered. He said that no one can force another to accept any religion or a sect (freedom of belief).[79] Also, everyone has the right to perform or neglect, if he so wishes, obligations of any religion he chooses (freedom of worship), such as the right to not fast during Ramadan.[80]

Religion and politics

According to historian Kemal Karpat, the movements that perceive Islam as a political movement or particularly the view of Islam as a political religion hold the position that Atatürk was not a "true believer" or "religious Muslim". It is normal that this perspective was adapted, Karpat says: "He was not against Islam, but those who are against his political power using the religious arguments."[1]

Journalist Grace Ellison wrote in her book Turkey To-Day:

"I have no religion, and at times I wish all religions at the bottom of the sea. He is a weak ruler who needs religion to uphold his government; it is as if he would catch his people in a trap. My people are going to learn the principles of democracy, the dictates of truth and the teachings of science. Superstition must go. Let them worship as they will; every man can follow his own conscience, provided it does not interfere with sane reason or bid him against the liberty of his fellow-men."[81]

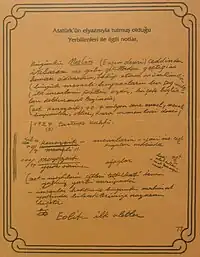

However, according to Atatürk's notebooks, he states in his own handwriting that a British journalist (referring to Grace Ellison) wrote what he did not say and distorted what he said:

A British newspaper reporter is talking to me. She writes things I have not said and interprets things I have said against us. I forbade her. She had promised. I realized that she is in fact a spy along with the people in Istanbul.

[82]

On 1 November 1937, his speech in parliament he said:

It is known by the world that, in our state administration, our main program is the Republican People's Party program. The principles it covers are the main lines that illuminate us in management and politics. But these principles should never be held equal to the dogmas of books that are known to have descended from the heavens. We have received our inspirations directly from life, not from the heavens or unseen.[83]

- Religion of the Arabs

Atatürk described Islam as the religion of the Arabs in his own work titled Vatandaş için Medeni Bilgiler by his own critical and nationalist views:

Even before accepting the religion of the Arabs, the Turks were a great nation. After accepting the religion of the Arabs, this religion, didn't effect to combine the Arabs, the Persians and Egyptians with the Turks to constitute a nation. (This religion) rather, loosened the national nexus of Turkish nation, got national excitement numb. This was very natural. Because the purpose of the religion founded by Muhammad, over all nations, was to drag to an including Arab national politics.[84]

Last days, 1937–1938

During 1937, indications of Atatürk's worsening health started to appear. In the early 1938, while he was on a trip to Yalova, he suffered from a serious illness. After a short period of treatment in Yalova, an apparent improvement in his health was observed, but his condition again worsened following his journeys first to Ankara, and then to Mersin and Adana. Upon his return to Ankara in May, he was recommended to go to Istanbul for treatment, where he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver.

During his stay in Istanbul, he made an effort to keep up with his regular lifestyle for a while, heading the Council of Ministers meeting, working on the Hatay issue, and hosting King Carol II of Romania during his visit in June. He stayed on board his newly arrived yacht, Savarona, until the end of July, after which his health again worsened and then he moved to a room arranged for him at the Dolmabahçe Palace.

Death and funeral

.jpg.webp)

Atatürk died at the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul, on 10 November 1938, at 09:05 am, aged 57. According to the overlapping testimonies of Kılıç Ali and Hasan Rıza Soyak, who were with Atatürk at the time of his death, Atatürk's last words were the religious greeting, "aleykümesselâm" (Wa alaykumu s-salam).[85][86] It is thought that he died of cirrhosis of the liver.[87] Atatürk's funeral called forth both sorrow and pride in Turkey, and seventeen countries sent special representatives, while nine contributed with armed detachments to the cortège.[88]

In November 1953, Atatürk's remains were taken from the Ethnography Museum of Ankara by 138 young reserve officers in a procession that stretched for two miles (3 km) including the president, the premier, every cabinet minister, every parliamentary deputy, every provincial governor and every foreign diplomat.[89]

One admiral guarded a velvet cushion which bore the Medal of Independence; the only decoration, among many others held, that Atatürk preferred to wear. The Father of the Turks finally came to rest at his mausoleum, the Anıtkabir. An official noted: "I was on active duty during his funeral, when I shed bitter tears at the finality of death. Today I am not sad, for 15 years have taught me that Atatürk will never die."[89]

His lifestyle had always been strenuous. Alcohol consumption during dinner discussions, smoking, long hours of hard work, very little sleep, and working on his projects and dreams had been his way of life. As the historian Will Durant had said, "men devoted to war, politics, and public life wear out fast, and all three had been the passion of Atatürk."

Will

In his will written on 5 September 1938, he donated all of his possessions to the Republican People's Party, bound to the condition that, through the yearly interest of his funds, his sister Makbule and his adopted children will be looked after, the higher education of the children of İsmet İnönü will be funded, and the Turkish Language Association and Turkish Historical Society will be given the rest.

Publications

Atatürk published many books and kept a journal throughout his military career. Atatürk's daily journals and military notes during the Ottoman period were published as a single collection. Another collection covered the period between 1923 and 1937 and indexes all the documents, notes, memorandums, communications (as a President) under multiple volumes, titled Atatürk'ün Bütün Eserleri ("All of the Works of Atatürk").

The list of books edited and authored by Atatürk is given below ordered by the date of publication:

- Takımın Muharebe Tâlimi, published in 1908 (Translation from German)

- Cumalı Ordugâhı – Süvâri: Bölük, Alay, Liva Tâlim ve Manevraları, published in 1909

- Ta’biye ve Tatbîkat Seyahati, published in 1911

- Bölüğün Muharebe Tâlimi, published in 1912 (Translation from German)

- Ta’biye Mes’elesinin Halli ve Emirlerin Sûret-i Tahrîrine Dâir Nasâyih, published in 1916

- Zâbit ve Kumandan ile Hasb-ı Hâl, published in 1918

- Nutuk, published in 1927

- Vatandaş için Medeni Bilgiler, published in 1930 (For high school civic classes)

- Geometri, published in 1937 (For high school math classes)

See also

Notes

- The law stated that the surname "Atatürk" may be used only by Mustafa Kemal, the first President of Turkey. The surname "Atatürk" can be divided in two parts, "Ata" and "Türk," whereby "Ata" means "father" or "ancestor", while Türk denotes simply "Turk," the "Turkish people." Thus, "Atatürk" best translates to "Father of Turkish People". The current common practice in Turkey as well as abroad is to refer to him as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

References

- Karpat, "The Personality of Atatürk", pp. 893–99.

- Carl Cavanagh Hodge, Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1914, p. 393; ISBN 978-0-313-33404-7

- Balfour Kinross, Patrick (3 May 2012). Atatürk: Rebirth of a Nation. Orion. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-78022-444-2.

- Güneş, İhsan (2011). Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi, "Sakarya Savaşı", Prof. Dr. İlhan Güneş. Anadolu Universitesi. ISBN 9789754927436. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- Turkish Justice Department website, Article Ataturk

- Profile, smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Enis Dinç (2020). Atatürk on Screen: Documentary Film and the Making of a Leader. p. 180.

- "TURKEY: Door to Dreamland". Time. 19 May 1941.

- Zürcher, Erik Jan (1984). The Unionist factor: the rôle of the Committee of Union and Progress in the Turkish National Movement, 1905–1926. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 106.

- "Atatürk'ün Doğum Tarihi" (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Mango, Andrew, Atatürk: the biography of the founder of modern Turkey, (Overlook TP, 2002), p. 27.

- Mango, Atatürk, p. 27

- Lou Giaffo: Albania: eye of the Balkan vortex

- Jackh, Ernest, The Rising Crescent, (Goemaere Press, 2007), p. 31, Turkish mother and Albanian father

- Isaac Frederick Marcosson, Turbulent Years, Ayer Publishing, 1969, p. 144.

- Richmond, Yale, From Da to Yes: understanding the East Europeans, (Intercultural Press Inc., 1995), p. 212.

- Falih Rıfkı Atay, Çankaya: Atatürk'ün doğumundan ölümüne kadar, İstanbul: Betaş, 1984, p. 17. (in Turkish)

- Vamık D. Volkan & Norman Itzkowitz, Ölümsüz Atatürk (Immortal Atatürk), Bağlam Yayınları, 1998, ISBN 975-7696-97-8, p. 37, dipnote no. 6 (Atay, 1980, s. 17)

- Şevket Süreyya Aydemir, Tek Adam: Mustafa Kemal, Birinci Cilt (1st vol.): 1881–1919, 14th ed., Remzi Kitabevi, 1997; ISBN 975-14-0212-3, p. 31. (in Turkish)

- Great leaders, great tyrants?: Contemporary views of World rulers who made history, Arnold Blumberg, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995; ISBN 0313287511, p. 7. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- His Story: Mustafa Kemal and Turkish Revolution, A. Baran Dural, iUniverse, 2007; ISBN 0595412513, pp. 1–2. 29 August 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Whether, like most Macedonians, he had about him a touch of the hybrid —perhaps of the Slav or Albanian—can only be a matter for surmise." Atatürk: a biography of Mustafa Kemal, father of modern Turkey, by Baron Patrick Balfour Kinross, Quill/Morrow, 1992; ISBN 0688112838, p. 8.

- Mango, Atatürk, p. 38

- Çalışlar, İpek (4 October 2013). Madam Atatürk: The First Lady of Modern Turkey. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-847-3.

- Turgut, Pelin (1 July 2006). "Turkey in the 21st century: The Legacy Of Mrs Ataturk". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- Güler, Emrah (25 August 2006). "Atatürk, his wife and her biographer". Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- BBC News Atatürk diaries to remain secret, BBC, 4 February 2005.

- Terra Anatolia—Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938), terra-anatolia.com. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Aydemir, Tek Adam: Cilt I, p. 20

- Karpat, "The Personality of Atatürk" page 897-898

- Mahmut Goloğlu, (1971) Milli Mücadele Tarihi 5. Cilt [The History of the National Struggle Volume V]

- Ferris, John (2003). "'Far too dangerous a gamble'? British intelligence and policy during the Chanak crisis, September-October 1922". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 14 (2): 139–184. doi:10.1080/09592290412331308851. ISSN 0959-2296.

- MacFie, A. L. (2002). "British Views of the Turkish National Movement in Anatolia, 1919-22". Middle Eastern Studies. 38 (3): 27–46. ISSN 0026-3206.

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon (2014) [1st pub. 1994]. "Introduction". Atatürk. Profiles In Power. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-317-89735-4.

- Balfour, Patrick (1992) [1st pub. 1965]. Ataturk: A Biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Modern Turkey. Quill/Morrow. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-688-11283-7.

Women, for Mustafa, were a means of satisfying masculine appetites, little more; nor, in his zest for experience, would he be inhibited from passing adventures with young boys, if the opportunity offered and the mood, in this bisexual fin-de-siècle Ottoman age, came upon him.

- Armstrong, Harold Courtenay (1972) [1st pub. 1932]. Grey Wolf, Mustafa Kemal: An Intimate Study of a Dictator. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. pp. 37, 253–254. ISBN 978-0-8369-6962-7.

"In the reaction he lost all belief in women and for the time being became enamoured of his own sex. [...] He started a number of open affairs with women, and with men. Male youth attracted him.

- Orga, İrfan; Orga, Margarete (1962). Atatürk. M. Joseph. p. 92. OCLC 485876812.

He had never loved a woman. He knew men, and was accustomed to command. He was used to the rough camaraderie of the Mess, the craze for a handsome young man, fleeting contacts with prostitutes.

- Özmen, Ceyda (2019). "Retranslating in a Censorial Context: H.C. Armstrong's Grey Wolf in Turkish". In Albachten, Özlem Berk; Gürçağlar, Şehnaz Tahir (eds.). Perspectives on Retranslation: Ideology, Paratexts, Methods (1 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203702819-4/retranslating-censorial-context-ceyda-%C3%B6zmen. ISBN 978-0-203-70281-9.

- Saki, Ayşe (2014). A Critical Discourse Analysis Perspective on Censorship in Translation: A Case Study of the Turkish Translations of Grey Wolf (Master thesis). Hacettepe University. pp. 113–114, 118.

- Stern, Keith; McKellen, Ian (2009). Queers in History: The Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Historical Gays, Lesbians and Bisexuals. Dallas, Texas: BenBella. ISBN 978-1-933771-87-8.

- Larivière, Michel (2017). Dictionnaire historique des homosexuel-le-s célèbres (in French). Paris: La Musardine. p. 32. ISBN 978-2-84271-779-7.

- Girard, Quentin (8 May 2014). "Alexandre le Grand et Flaubert sortent du placard". Libération (in French). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Denizli, Vedat; Kart, Emine (29 March 2007). "Backtracking on Atatürk slur, Belgium calls it 'copy and paste accident'". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 1 April 2007.

- "Polémique autour de la lutte contre l'homophobie". La Libre Belgique (in French). 30 March 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Dorzée, Hugues (30 March 2007). "Homophobie, suivez le guide..." Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "YouTube Ban – DW – 03/08/2007". dw.com. 8 March 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- "Turkey pulls plug on YouTube over Ataturk 'insults'". The Guardian. Associated Press. 7 March 2007. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- "Turkish Angora A Zoological Delight". Pet Publishing Inc. Archived from the original on 7 December 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "History of Atatürk Orman Çiftliği". aoc@aoc.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

"Yeşili görmeyen gözler renk zevkinden mahrumdur. Burasını öyle ağaçlandırınız ki kör bir insan dahi yeşillikler arasında olduğunu fark etsin" düşüncesi Atatürk Orman Çiftliği'nin kurulmasında en önemli etken olmuştur.

- Aydıntaşbaş, Aslı (7 December 2008). "Why I Love Turkey's Smoking, Drinking Founding Father." Forbes. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Kenyon, Peter (7 June 2013). "Not Everyone Cheers Turkey's Move To Tighten Alcohol Rules." NPR. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon (2014). Ataturk. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9781317897354. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Atatürkʼün Uşağı İdim, Hürriyet Yayınları, 1973, p. 267

- Romanya Dışişleri Bakanı Antonescu İle Konuşma (in Turkish)

- Political Islam in Turkey: Running West, Heading East? Author G. Jenkins, Publisher Springer, 2008, ISBN 0230612458, p. 84.

- Düzel, Neşe (6 February 2012). "Taha Akyol: Atatürk yargı bağımsızlığını reddediyor"

- Reşat Kasaba, "Atatürk", The Cambridge history of Turkey: Volume 4: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, 2008; ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3 p. 163. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Political Islam in Turkey by Gareth Jenkins, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, p. 84; ISBN 0230612458

- Atheism, Brief Insights Series by Julian Baggini, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009 ISBN 1402768826, p. 106.

- Islamism: A Documentary and Reference Guide, John Calvert John, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008 ISBN 0313338566, p. 19.

- ...Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the secular Turkish Republic. He said: "I have no religion, and at times I wish all religions at the bottom of the sea..." The Antipodean Philosopher: Interviews on Philosophy in Australia and New Zealand, Graham Oppy, Lexington Books, 2011 ISBN 0739167936, p. 146.

- Phil Zuckerman, John R. Shook, The Oxford Handbook of Secularism, Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 0199988455, p. 167.

- Tariq Ramadan, Islam and the Arab Awakening, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0199933731, p. 76.

- "Atatürk'ün Fikir ve Düşünceleri". T.C. Başbakanlık Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Başkanlığı.

- Ethem Ruhi Fığlalı (1993) "Atatürk and the Religion of Islam" Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Dergisi, Sayı 26, Cilt: IX.

- Prof. Utkan Kocatürk, Atatürk'ün Fikir ve Düşünceleri (Atatürk ve Din Eğitimi, A. Gürtaş, p. 26), Atatürk Research Center, 2007; ISBN 9789751611741

- Prof. Ethem Ruhi Fığlalı, "Atatürk'ün Din ve Laiklik Anlayışı", Atatürk Research Center, 2012; ISBN 978-975-16-2490-1, p. 86

- Atatürk'ün Söylev ve Demeçleri, Ankara 1959, 2. Baskı, II, 66–67; s. 90. III, 70

- "İşte Atatürk'ün harbe giderken ettiği dua". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Ahmet Taner Kışlalı "Kemalizm, Laiklik ve Demokrasi [Kemalism, Laicism and Democracy]" 1994

- Nutuk, vol. 11, p. 708.

- "Atatürk ve Din" (PDF). T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanlığı. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2014.

- Akbaba, Turgay (2020). From the Terrible Turk to the Incredible Turk: Reimagining Turkey as an American Ally, 1919-1960. cdr.lib.unc.edu (Thesis). doi:10.17615/0x8y-hj58. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Atatürk İslam için ne düşünüyordu?

- Medenî Bilgiler ve M. Kemal Atatürk'ün El Yazıları [Civics and M. Kemal Atatürk's Manuscripts] (1998) by Afet İnan, p. 438. "Kralların ve padişahların istibdadına dinler mesnet olmuştur."

- Fığlalı "Atatürk and the Religion of Islam"; "But to mention that religion is a matter of relationship and communication between Allah and his servant" [recited from Kılıç Ali, Atatürk'ün Hususiyetleri, Ankara, 1930, p. 116]

- Jacob M. Landau (1984). Atatürk and the Modernization of Turkey. London ; New York: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 90-04-07070-2. page 217

- M. Orhan Tarhan, "Should Government Teach Religion?", The Atatürk Society of America

- Kılıç Ali, Atatürk'ün Hususiyetleri, Ankara, 1930, p. 57

- A. Afet İnan, M. Kemal Atatürk'ten Yazdıklarım, İstanbul, 1971, pp. 85–86.

- Grace, Ellison (1928). Turkey To-day. London, United Kingdom: Hutchinson. p. 24.

- Atatürk, Mustafa Kemal (2004). Atatürk'ün not defterleri (Atatürk's notebooks). Volume 12 (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Ankara: Genelkurmay Basım Evi. p. 125. ISBN 978-975-409-246-2.

- Atatürk'ün Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi'nin V. Dönem 3. Yasama Yılını Açış Konuşmaları (in Turkish). "... Dünyaca bilinmektedir ki, bizim devlet yönetimimizdeki ana programımız, Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi programıdır. Bunun kapsadığı prensipler, yönetimde ve politikada bizi aydınlatıcı ana çizgilerdir. Fakat bu prensipleri, gökten indiği sanılan kitapların doğmalarıyla asla bir tutmamalıdır. Biz, ilhamlarımızı, gökten ve gaipten değil, doğrudan doğruya yaşamdan almış bulunuyoruz."

- Afet İnan, Medenî Bilgiler ve M. Kemal Atatürk'ün El Yazıları, Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1998, p. 364.

- Güler, Ali (2013). Atatürk'ün son sözü aleykümesselâm (Atatürk's last words were alaykumu s-salam) (in Turkish) (1st ed.). İstanbul: Yeditepe Yayinevi. ISBN 978-605-5200-32-9.

- Ali, Kılıç (2017). Turgut, Hulûsi (ed.). Atatürk'ün sırdaşı Kılıç Ali'nin anıları (12th ed.). İstanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları. p. 659. ISBN 978-975-458-617-6.

- "Kemal Atatürk". NNDB. Retrieved 7 August 2008.

- Mango, Atatürk, p. 526.

- "The Burial of Atatürk". Time. 24 November 1953. pp. 37–39. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

Sources

- Prints

- Vamık D. Volkan and Norman Iskowitz (1984). The Immortal Atatürk. A Psychobiography. London; New York: Univ. Chicago Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-226-86389-4.

- Mango, Andrew (2002) [1999]. Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey (Paperback ed.). Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-58567-334-X.

- Mango, Andrew (2004). Atatürk. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6592-2.

- Aydemir, Şevket Süreyya (2003). Tek Adam: Cilt I. Remzi Kitabevi. ISBN 975-14-0672-2.

- Journals

- Karpat, Kemal H.; Volkan, Vamık D.; Itzkowitz, Norman (October 1985). "The Personality of Atatürk". The American Historical Review. New York: Macmillan. 90 (4): 893–899. doi:10.2307/1858844. JSTOR 1858844.

- Volkan, Vamık D. (1981). "Immortal Atatürk—Narcissism and Creativity in a Revolutionary Leader". Psychoanalytic Study of Society. New York: Psychohistory Press. 9: 221–255. ISSN 0079-7294. OCLC 60448681.

- Fığlalı, Ethem Ruhi (1993). "Atatürk and the Religion of Islam". Atatürk Araştırma Dergisi. Ankara: Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Başkanlığı. IX (26).

- News

- "The Burial of Atatürk". Time. 23 November 1953. pp. 37–39. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- Web

- "Mustafa Kemal Atatürk". Turkish Embassy website. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- "Kemal Öz Adlı Cümhur Reisimize Verilen Soyadı Hakkında Kanun (The law about to be given surname to our President which self the name Kemal)" (PDF). mevzuat.gov.tr (in Turkish). Republic of Turkey Prime Ministry General Directorate of Development of Legislation and Publication website. 24 December 1934. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

.jpg.webp)