Peryn

Peryn (Russian: Перынь, IPA: [pʲɪˈrɨnʲ]) is a peninsula near Veliky Novgorod (Russia), noted for its medieval pagan shrine complex,[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] and for its later well-preserved monastery.

The Peryn islet during the extreme spring flooding of 2009 which recreated temporarily its appearance at the time of the construction of the shrine complex. (Lake Ilmen visible on the horizon) | |

| Location | Veliky Novgorod, Novgorod Oblast, Russia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 58°28′22″N 31°16′25″E |

Location

The Peryn peninsula is at the confluence of Lake Ilmen and the River Volhov, 6 km (3.7 mi) south of the city of Veliky Novgorod. In the Dark Ages, the city was developed not far from Peryn, at Ruerikovo Gorodische also known as Holmgård,[10] but its business and social activities were later moved to form today's city centre.[11][12] The area south of Novgorod, including Peryn, is therefore considered part of the historic surroundings of Veliky Novgorod.[nb 1]

Historically, Peryn was an islet formed by the River Volkhov and two small rivers called Rakomka and Prost. It could only be reached by boat. The conditions changed significantly after a dam was constructed in the 1960s to provide access for vehicles.[9] After the 1960s Peryn looked like a peninsula but now it looks more like a hill which only becomes a peninsula when floods arrive in the spring.[13][14]

Pagan history

Cult of Perun in Peryn and in Novgorod

Novgorod was a centre of Slavic paganism in the Dark Ages. Accordingly, the Peryn island appears to have played a role similar to that of the Vatican Hill in the sense of its functions in the medieval Novgrorod and its later history. The name "Peryn" is related to the Slavic god Perun,[2][17][18] whose shrine was there in the 10th century.[1] The results of archaeological excavations under the guidance of Valentin Sedov described in his survey of Peryn,[nb 2] suggest that Peryn was a sacred place from ancient times.[1] It is likely that the area has seen several pagan shrines, replacing one with another over time.[19] The best known is the heathen shrine, established there in 980. Early Slavs used to set up anthropomorphic statues of wood, picturing their gods to serve the cult, and in 980 in Peryn it was carried out this way:

|

"In the year 6488 [980] <...> Vladimir appointed his uncle Dobrynya to rule in Novgorod. And Dobrynya came over in Novgorod. [And he] set up an idol of Perun above the Volkhov River [i.e. on a high bank], and Novgorodians offer him [Perun] sacrifices as to a deity" ____________________ "В лѣто ҂s҃.у҃.п҃и [6488 (980)] <…> Володимиръ же посади Добрьиню оуӕ своєго в Новѣгородѣ. И пришєд Добрынѧ Новугороду. Постави Пєруна кумиръ надъ рѣкою Волховомъ, и жрѧхуть єму людє Новгородьстии акы Бу҃" (Old East Slavic language) |

| - The Primary Chronicle[20] |

The Perun cult can be considered an aspect of Slavic mythology combining Greek and Scandinavian mythology with authentic Slavic features. Parallels can therefore be seen between Perun, Jupiter, Zeus, and Thor. Like the well-known deities, Perun was the head of a pantheon. He was a thunder god too, who overthrew his enemy Veles down under the roots of the World Oak. Adam Olearius, who visited Peryn in 1654, describes the cult of Perun in Peryn as follows:

|

"Novgorodians, when they were pagans, had an idol called Perun, i.e. the god of fire, as Russians call fire “Perun”. A monastery is erected now in the place where the idol stood, and the monastery holds the name of the idol and is called the Perunic monastery. The deity looks like a man with a lightning- or ray-shaped flint in his hand. Day and night they kept an eternal flame burning with oak firewood as a sign of worship to the deity. And if the priest of the cult allowed the fire to go out accidentally, he was put to death." ____________________ "Новгородцы, когда были еще язычниками, имели идола, называвшегося Перуном. т. е. богом огня, ибо русские огонь называют "перун". И на том месте, где стоял этот их идол, построен монастырь, удержавший имя идола и названный Перунским монастырем. Божество это имело вид человека с кремнем в руке, похожим на громовую стрелу (молнию) или луч. В знак поклонения этому божеству содержали неугасимый ни днем, ни ночью огонь, раскладываемый из дубового леса. И если служитель при этом огне по нерадению допускал огню потухнуть, то наказывался смертью" (Modern Russian translation) |

| - "Travels of the Ambassadors sent by Frederic, Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy and the King of Persia", 1656[21][22] |

As paganism implies many deities, Perun was not the only god in the heathen pantheon of Novgorod. Volos, whose shrine was presumably located on the site of the Church of St. Vlasi,[23][24] was another deity worshipped in the city.[24] But it seems that his cult was not favoured by Vladimir the Great,[25] who excluded Volos from his pagan pantheon.[25][nb 3] The first Christians erected the Church of the Transfiguration in Novgorod,[26] but the government in Kiev was indifferent towards their religion, until Vladimir the Great was baptized in 988.[27][28] By contrast to the folk cults of Volos and Jesus, the cult of Perun was probably seen as the royal (official) cult,[29][30] arranged on Peryn Island close to the royal residence on the Holmgård Hill.[31]

When the Russian state was Christianized in 989, the heathen religion was subjected to persecution. The citizens of Novgorod first tried to protect their deities, reportedly saying: "We would rather die than allow our gods to be outraged".[32] The Novgorodians ravaged and plundered the house of Dobrynya, who was appointed to Christianize Novgorod, and beat up his wife.[33] However, Dobrynya with the help of Putyata the warlord stifled the riot and completed his Christianization by force.[2][34] Subsequently, the Peryn shrine, being the main spiritual complex in the second most important city in the Russian state,[35] was ravaged and destroyed. No doubt, the process of ravaging was ritualized in Peryn, demonstrating that the new religion had overthrown its predecessor.[2] According to the chronicle, it happened this way in Peryn:

|

"In the year 6497 [989] Vladimir was baptized, and all Russian land [as well]. And [they] appointed a metropolitan [to serve] in Kiev, and an archbishop – in Novgorod. <…> And the archbishop Ioakim Korsunianin came over to Novgorod, and destroyed the altars, chopped down the idol of Perun, and ordered it to be dragged into Volhov, tying [it] with ropes, dragging [it] on dirt, beating [it] with sticks, and [Joachim the Korsunian] ordered everyone not to accept it [the idol] anywhere [i.e. not to pull it ashore]. A settler of the valley of Pitba [a river] went to the river in the early morning, preparing to go to the city to sell pottery; [the idol of] Perun hit the shore, and [the man] pushed away the idol with a stick, saying: “You say, Perun, you had enough to eat and drink, so get away now”, and the vicious floated away" ____________________ "В лѣта шесть тысящь четырѣста деветьдесятъ седмаго. Крѣстися Володимеръ и вся земля Руская. И поставиша в Киеве митрополита, а Новугороду архиепископа… И приидѣ Новугороду Акимъ архиепископъ Коръсунянинъ, и требища раздруши, и Перуна посече, и повеле волочи Волховомъ, поверзавше оужи, волочаху по калу, бьюще жезьлиемъ; и заповѣда никомуже нигдѣже не приати. Идѣ пидьблянинъ рано на реку, хотя горонци вести в городъ; оли Перунъ приплы ко берви, и отрину и шесътомъ: «ты, рече, Перушиче, досыть еси пилъ и ѣлъ, а нынѣ поплови прочь»; и плы съ свѣта окошное" (Old East Slavic language, Old Novgorod dialect, adopted writing) |

| - Novgorod First Chronicle[36] |

The Christianization and ravaging of the shrines was a great tragedy for the people.[37] They wept and cried out for mercy with their gods, and Dobrynya reportedly mocked them in response: "What, madmen? Are you mourning those who are not able to protect themselves [on their own]? What benefits do you expect from them?".[38] Some people, who did not will to betray their deities, started to pretend they have already been baptized.[39] In response, Dobrynya ordered to check crosses and “not to believe and to baptize”[40] those who wear no cross.

Whatever it was, the old religion along with the cult of Perun were not easy to oust from the social mind of the city. It was displaced at the level of social underself, rising in Novgorodian fables, sagas, oral tales and traditions. One of the legends, about the mace of Perun, is fixed in the Novgorod Fourth Chronicle.

|

[During the process of the ravaging, the idol of] "Perun was possessed by a demon, who started to scream: “O woe! O me! I am in malicious hands!”. And he [the idol] was thrown into Volhov. He [the idol] swam over [the pillars of] the Great Bridge, throwing a mace down on the bridge and saying: “Let Novgorodian children remember me with that”. Now crazy people fight themselves with maces, entertaining demons. And everyone was ordered not to accept him [i.e. not to pull the idol ashore]" ____________________ "Вшелъ бѣаше бѣсъ въ Перуна и нача кричати: «О горѣ! Охъ мнѣ! Достахся немилостивымъ симъ рукамъ». И вринуша его въ Волховъ. Онъ же поплове сквозѣ Велии мостъ, верже палицю свою на мостъ и рече: «На семъ мя поминаютъ Новгородьскыя дѣти». Еюже нынѣ безумнiи убивающиеся утѣху творять бѣсом. И заповѣда нiкомуже нигдѣже не переяти его" (Old East Slavic language, Old Novgorod dialect, adopted writing) |

| - Novgorod Fourth Chronicle[41][42] |

The legend about the mace of Perun, thrown down on the Great Bridge, was seminal and linked with the Novgorodian tradition of arranging wrestling matches between the citizens of different districts of the medieval city.[43][44] The significant attribute of the wrestling battles were maces (a symbol of Perun): a sidenote in the Book of Royal Degrees tells us that the maces with tin pips for use in the wrestling matches were kept inside the Church of Boris and Gleb, and Nikon the Metropolitan burned them down in 1652, stopping “that devilish trizna [after the deity]”.[45] The tradition is described by Sigismund von Herberstein, who visited Novogorod in 1517 and 1526.

|

"Even now it happens from time to time on certain days of the year, that this voice of Perun [a special Novgorodian name for battle-cry] may be heard, and on these occasions the citizen suddenly run together and lash each other with ropes, and such a tumult arises therefrom, that all the effort of the governor can scarcely assuage it." |

| - Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii, 1549, original English translation[17] |

Novgorodian society has carefully guarded its memories of Perun and Peryn throughout the centuries. The Saga of Sloven and Rus, created in 1634, contains one more legend on the matter; the excerpt from the Saga below also describes certain Slavic heathen traditions and rituals. Two centuries later, in 1859, the Russian writer Pavel Yakushkin, when he was near Novgorod, wrote down an oral legend about Perun the serpent and Peryn, told to him by a Novgorodian fisherman.[46] In fact, the oral legend is cognate with the plot of the Saga of Sloven and Rus.[47] Even at the turn of the 20th century there was a tradition to drop a coin in the river Volhov while passing Peryn by boat.[48]

|

"...The elder son of Sloven called Volhv[nb 4] was a devil worshipper and a wizard, and was ferocious towards people. He [used to] achieve many dreams by means of devilish tricks and turn himself into a ferocious beast, a crocodile, lying down deeply in the river Volhov on a waterway, devouring some who did not worship him, and lacerating and drowning others. For that sake, people called him the real god of the thunder, or Perun, as in Russian [the author means the ancient language, Old East Slavic ] thunder is called “Perun”. He, the damned wizard, erected a small burg for the sake of midnight dreamings and devilish assemblies in a certain place called Peryn [in the original variant - Perynia], where an idol of Perun stood [before]. And they gossip about the wizard ignorantly: "[He] was appointed to [the pantheon of] gods, embodying the Vicious". We venture to take our true Christian word to announce about the damned wizard and the demon: he was overthrown and drowned in the river Volhov, and by devilish tricks his corpse was belched ashore against his burg on [the bank of] the river Volhov still called Peryn. And he was buried at that place by heretics with a loud death wail and a great pagan trizna, and they made a large mound on his grave according to the pagan custom. And on the third day of the trizna the ground slumped in, absorbing the crocodile’s odious body, and the grave fell down into the depths of hell, and still the hole has reportedly not been filled." ____________________ "Больший же сын оного князя Словена Волхв бесоугодник и чародей и лют в людех тогда бысть, и бесовскими ухищреньми мечты творя многи, и преобразуяся во образ лютаго зверя коркодила, и залегаше в той реце Волхове путь водный, и не поклоняющих же ся ему овых пожираше, овых же испроверзая и утопляя. Сего же ради людие, тогда невегласи, сущим богом окаяннаго того нарицая и Грома его, или Перуна, рекоша, руским бо языком гром перун именуется. Постави же он, окаянный чародей, нощных ради мечтаний и собирания бесовскаго градок мал на месте некоем, зовомо Перыня, иде же и кумир Перунов стояше. И баснословят о сем волхве невегласи, глаголюще: "В боги сел, окаяннаго претворяюще". Наше же християнское истинное слово с неложным испытанием многоиспытне извести о сем окаяннем чародеи и Волхове, яко зле разбиен бысть и удавлен от бесов в реце Волхове и мечтаньми бесовскими окаянное тело несено бысть вверх по оной реце Волхову и извержено на брег противу волховнаго его градка, иде же ныне зовется Перыня. И со многим плачем тут от неверных погребен бысть окаянный с великою тризною поганскою, и могилу ссыпаша над ним велми высоку, яко же обычай есть поганым. И по трех убо днех окаяннаго того тризнища проседеся земля и пожре мерзкое тело коркодилово, и могила его просыпася с ним купно во дно адово, иже и доныне, яко ж поведают, знак ямы тоя не наполнися" (Early Modern Russian) |

| - The Saga about Sloven and Rus, 1634[49] |

As frequently occurs after a Christianization, people reconcile the mental conflict in their minds after changing their religion, substituting heathen gods with Christian saints, making it easier for them to virtually adhere to the old cult, traditions, symbolism and values without betraying the Christian religion. In the case of Novgorod, the imago of Perun was substituted with the figures of God the Father and Elias the Prophet.[50] In the first case it is plays the role of Perun with the head of a pantheon; in the second, Elias the Prophet carries the attributes of Perun: he moves across the sky on a chariot, thundering and flashing (lightning) like Perun.

Simultaneously, as explicitly shows The Saga of Sloven and Rus (1634) cited above, the imago of Perun incorporates the peculiarities of the Devil, embodying a character who had been overthrown by the Christian religion; the one defeated in the name of the God and displaced in the underworld, who is opposed to the God, ruling his own (pagan) world.

Thus, the image of Perun in Novgorod is a complicated social phenomenon.

.jpg.webp) The pantheon of the Vladimir the Great in Kiev as shown in the Radziwiłł Chronicle. The figure with a ray-shaped subject in his hands on the top of the hill is Perun

The pantheon of the Vladimir the Great in Kiev as shown in the Radziwiłł Chronicle. The figure with a ray-shaped subject in his hands on the top of the hill is Perun

The fire ascension of Elias the prophet, the Novgorodian icon. Late 15th to early 16th centuries

The fire ascension of Elias the prophet, the Novgorodian icon. Late 15th to early 16th centuries

Heathen shrine

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Founded | 980 A.D. (the last shrine) |

| Abandoned | 989 A.D. |

| Cultures | Slavic paganism |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1951, 1952 |

| Archaeologists | Valentin Sedov, Artemi Artsyhovky |

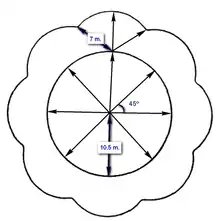

In 1951 an archaeological expedition under the direction of Valentin Sedov revealed the remains of a pagan temple complex.[51] According to the report by Sedov, the shrine was located in the centre of Peryn Islet, on the historical top of the Peryn Hill.[51] The remains were preserved quite well,[1] though some parts were spoiled significantly by diggings many centuries ago.[52] The shrine is circular-shaped with a diameter of 21 m (69 ft), encompassing a shallow ditch a metre in depth.[52] The construction is of regular (geometrical) forms.[52] The ditch has a sharp internal edge, and a flat external edge.[52] The ditch has eight bulges with the radius of 7 m (23 ft).[53] The bulges are aligned to the points of the compass.[52][54] The circle's centre has a hole of 65 cm (26 in) in width.[15] Sedov in his survey suggests that the shrine's shape reflects the symbols of Perun.[53]

The excavations disproved the opinion that the Peryn Chapel was erected right on the site of the pagan shrine according to the Old Russian tradition of erecting churches on the places of pagan shrines.[51] The results of Sedov are consistent with those of Artemi Artsihovsky, who was looking for the remains of the shrine in the chapel's basement two years earlier (in 1948), and had not found them.[51]

The excavations confirmed the chronicle data that bonfires had burnt around the idol.[55] Heaps of charcoal and/or evidence of fire were revealed in every bulge.[52][56] Sedov in his survey ties that fact with what is known about the cult of Perun, and suggests that the bulges in the ditch were for ritual bonfires.[55] The eastern bulge is remarkable with an especially large heap of charcoal, indicating that an eternal flame might have been located there.[55] The remaining pyres are likely to have been in use from time to time (probably for ceremonies).[55] The samples of charcoal analyzed were from oak wood,[52] Perun’s tree. The excavations showed that the bonfires and the ditch were buried when the shrine was ravaged in ancient times.[1]

The hole in the centre of the circle is interpreted by Sedov as a groove for the wooden idol.[15] He found pieces of putrefied wood inside the hole[15] and argues in his report: the data from the Novgorod First Chronicle are confirmed, and the idol was hacked down during the process of destruction, leaving the base of the idol inside the hole.[1] Sedov in his survey draws a more complete and detailed picture of the destruction.[1] Based on the results of the excavations he claims: while one group of people was engaged in chopping the wooden idol down, another was covering the bonfires with soil and destroying the altar.[1] Then they all together buried the ditch.[1]

In 1952 Sedov continued the excavations and discovered two circle-shaped constructions of a smaller size to the sides of the main shrine.[57] Sedov asserts the constructions to be arranged there "not later than in the 9th century".,[58] meaning that the main shrine seems to replace some more ancient ones.[57] Russian historian Rybakov in his survey presumes a more ancient cult existed in Peryn before the cult of Perun.[59] Sedov found other constructions of later periods around the shrine, including graves and dugouts.[56]

There are other interpretations of Sedov's findings. Russian historians Vladimir Konetsky and Lev Klein argue that Sedov had found a burial mound, not a shrine.[60][61] They have not submitted any crucial counterarguments, though; they rather suggest an alternative version to interpret the findings. Nevertheless, graves discovered by Sedov within the construction are from later periods,[51] Sedov took part in the excavation himself,[51] his results are fully consistent with all the ancient written sources[62] and appear to be justified. He asserts in his survey: “undoubtedly, these are the remains of the Perun’s shrine”.[63] On the other hand, the debates are about whether Sedov discovered the very shrine, but the fact that a shrine to Perun was located in Peryn is widely accepted and causes no doubt.[6]

According to the scheme,[16] the photographer who made that picture of the monastery cells stood right on the place of the heathen shrine

According to the scheme,[16] the photographer who made that picture of the monastery cells stood right on the place of the heathen shrine

After Christianization

| The Peryn Skete | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Region | Orthodox Christianity |

| Status | active |

| Location | |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | I. Sokolov (the cells) |

| Style | cross-in-square (the church), eclecticism (the cells) |

| Groundbreaking | 11th century (the first church of wood) |

| Completed | 1840s (the cells) |

| Official name: The ensemble of the Peryn Skete | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1992 |

| Reference no. | 604 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Website | |

| http://georg.orthodoxy.ru/skit.htm (in Russian) | |

Monastery

The monastery was probably founded in Peryn soon after the pagan shrine was destroyed, when a wooden church was reportedly erected there.[64] The remains of the church were presumably discovered by Vasili Sedov while excavating the small northern shrine in 1952.[59] The wooden church had approximately the same dimensions as the present church of stone.[59] It had reportedly been preserved well for about 200 years, until it was replaced with the Peryn Chapel[9] which existed until contemporary times. Nevertheless, the first chronicled reference to the monastery was not made until 1386.[4] The chronicle tells us that the monastery was one of 24 cloisters burned down by the Novgorodians so that they would not be left to the followers of Dmitry Donskoy,[65] the great duke of Moscovy who acted against Novgorod in 1386.

The wooden Church of the Trinity was the second church to be built on Peryn Islet.[4][66] It was accompanied by a wooden refectory built in 1528.[4] All the wooden buildings were destroyed during the Swedish occupation of Novgorod in 1611 – 1617: the monastery was ravaged.[9] The Novgorod inventory for 1617 reported:

|

"The Perynsky monastery of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The church in the monastery of the Nativity of Our Lady has been ravaged. There are no cells or fence near the monastery. The elder Maxim is the only monk in the monastery. All his assets of the God's mercy [i.e. funded with donations] are a crucifix and five books." ____________________ "Пречистыя Богородицы Перынский монастырь. Храм в монастыре Рождество Богородицы разорен. Келей и ограды около монастыря нет. В монастыре старец один Максим. Церковной монастырской казны Божия милосердия у него крест благословящий да пять книг..." (modern Russian adaptation of the Early Modern Russian text) |

| -The inventory of Novgorod, 1617[67] |

To sustain and support the monastery after it had been ravaged in 1611 - 1617, it was merged with the Yuriev Monastery (the main monastery of Novgorod).[68] According to one source, this occurred in 1634,[69] according to another, in 1671.[70] After the secularization undertaken by Catherine the Great in 1764, the monastery was abolished, its assets were transferred to Yuriev Monastery, and all the buildings except the Church of the Nativity were disassembled.[9]

The monastery was revived in the 18th century thanks to Anna Orlova-Chesmenskaya and Photios the Archimandrite. Photios the Archimandrite, when he was a hieromonk in Saint Petersburg, dismissed the popular idea of the times emphasizing direct communication between a man and the God outside the influence of the church.[71] As a result, he was removed from Saint Petersburg and sent to Novgorod in 1821.[9] In 1822 he was appointed head of the Yuriev Monastery.[68] He was no longer considered an oppositionist when the new emperor, a deeply religious person, came to the throne in 1825.[72]

He undertook extensive repairs of the Yuriev Monastery and on Peryn Islet, relying on financial support from Duchess Anna Orlova-Chesmenskaya,[8] his rich god daughter. At first, Photios asked that Peryn Islet should be returned to Yuriev Monastery. After this had been agreed in 1824,[73] he arranged for major repairs to the Peryn Chapel: the walls were repaired thoroughly inside and out; the church’s interior was redecorated; an outbuilding was built up from the west side of the church; the floor and the dome were replaced.[68]

The church was sanctified once again in 1828.[68] The monastery was extended in the 1830s and in the beginning of the 1940s: the red-bricked cells for the monks were erected along with two small buildings for an abbot and an archimandrite in the same architectural style.[68] The monastery was provided with two utility buildings and surrounded by a brick wall; the complex was completed with a bell tower housing six bells.[9] The buildings (apart from the bell tower and the fence) still form part of the monastery complex today.

Finally, Photios succeeded in giving the monastery the status of skete in 1828[68] - a monastery with severe regulations, isolated from the outer world. The monks had many prescriptions, one of them being that women were only allowed to visit the monastery once a year on September 8, the day of the Nativity of Our Lady.[9]

After the 1917 October Revolution, the monastery was closed and ravaged once again.[9] A decree to abolish all the monasteries in the Novgorod governorate was issued by the new Regional Council in August 1919.[9] Subsequently, the bell tower, the fence and the southern utility building were disassembled for bricks.[9] The bricks were used to build a depository for ice in the monastery land.[9] The church was used as a storehouse.[9] The remaining buildings were transferred to a fishing enterprise.[9] When Novgorod was occupied during World War II, the battle line came close to the monastery, but it was not badly harmed.[9]

After the end of the war, the monastery was turned into a sanatorium.[9] A dam was built in the 1960s to connect Peryn Islet with the landmass.[9] That altered the water regime substantially, and the historical islet became a peninsula which only became an islet during the spring floods, and then into a hill. The monastery was transferred to the church in 1991.[9] Now monastery at Peryn is referred to as Yuriev Monastery.[9]

Church of the Nativity of Our Lady in Peryn

| The Peryn Chapel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Region | Orthodox Christianity |

| Status | active |

| Location | |

| Architecture | |

| Style | cross-in-square |

| Completed | presumably 1224 |

The church adopted a traditional name for the first Novgorodian church, being named in honour of the Mother of God, who was believed to be a patron of Novgorod. Archaeologists assert that the church was erected in the first half of the 13th century,[74] and the historian Leonid Krasnorechyev specifies the date as the year 1226,[75] when the elections of an archimandrite for the church are known to have been held.

The church is remarkable for its small dimensions: it is 7.5 m (25 ft) and 9 m (30 ft) in width. Despite that, it looks surprisingly holistic and large from the inside: the attention of the visitor is drawn to the ceiling which looks very high. The columns in the church are not massive in contrast to other churches of the period. The church has three wide portals.

The chapel is notable with the cross at its dome: its design includes a crescent. That was typical for ancient churches in Russia built in the pre-Mongol period. That is called “The Grapevine Cross” and symbolizes a vine. It has no ties with Islam and is based on the interpretation of the Gospel of John:

|

"I am the true vine, and my Father is the husbandman. Every branch in me that beareth not fruit, he taketh it away: and every [branch] that beareth fruit, he cleanseth it, that it may bear more fruit." |

| - John 15:1, 2[76] |

See also

Gallery

The gates of Peryn

The gates of Peryn the Church of the Nativity of Our Lady at Peryn

the Church of the Nativity of Our Lady at Peryn The cells (built in 1830s–1840s)

The cells (built in 1830s–1840s) The abbot chamber (built in 1830s–1840s). The architectural style is Eclecticism influenced by the National Romantic Style

The abbot chamber (built in 1830s–1840s). The architectural style is Eclecticism influenced by the National Romantic Style The abbot chamber

The abbot chamber The utility building (similar to the abbot chamber, built in 1830s–1840s)

The utility building (similar to the abbot chamber, built in 1830s–1840s) The memorial crucifix on the bank of Peryn

The memorial crucifix on the bank of Peryn

Notes

- See more about the historic monuments of Novgorod and surroundings at "Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO.

- See the full text of the survey by Sedov in Russian at Sedov 1953

- According to the Novgorod First Chronicle 1950, p. 128, the pantheon of Vladimir the Great after the reform was about Peroun (as the head), Hors, Dazhbog, Strib, Simargl and Mokosh. Volos was not included there; probably - as a character who is opposed to Peroun in the mythology.

- The name "Volhv" is an appellative of the word "volhv

Links and citations

- Sedov 1953, p. 99.

- Rybakov 1987, p. 253.

- Oleary 1870, pp. 80–81.

- Sedov 2009, p. 29.

- Tatischev 1994, p. 63.

- Nosov Evgeny 2007, pp. 379–381.

- Mansikka 2005, p. 89

- Mizeretsky 1885, p. 561

- The official webpage of the Peryn Skete

- Melnikova & Petruhin 1986, p. 72: "Показательно, что крупнейшие погосты располагались, как правило, вблизи древнейших племенных центров: Гнёздово - под Смоленском, Шестовица - под Черниговом, Городище - под Новгородом")

- Melnikova & Petruhin 1986, p. 75: "...В Новгороде, где жизнь на городище временно затухает в XI в., княжеская резиденция переносится на Ярославово Дворище")

- Nosov 1987, p. 74: "...Russian chronicles dated to the second half of the 17th century and the 18th century <...> informed that Novgorod had been laid of a new place not far from Slovensk, the old capital of the Ilmen Slavs, which was identified with Gorodishche.")

- Sedov 1953, p. 92

- Rybakov 1987, p. 255

- Sedov 1953, p. 98.

- Sedov 2009, p. 32.

- Herberstein 1852, p. 26.

- Jakobson 1955, p. 615.

- Rybakov 1987, p. 278.

- The Primary Chronicle 1908, clmn. 67

- Oleary 1870 pp. 80 - 81

- Rybakov 1987 pp. 254 - 255

- Yanin 1852, p. 38.

- Rybakov 1987, p. 252.

- Rybakov 1987, p. 769

- Tatischev 1768, p. 38

- Bibikov Michail 2003, pp. 108 - 109

- The Primary Chronicle 1908, clmn. 97

- Rybakov 1987, pp. 768 - 769

- Prohorov et al. 1997, p. 527

- Nosov 1987, p. 85

- Tatischev 1768, p. 39 "Лучше нам померети, неже боги наша дать на поругание", (Old East Slavic language, Old Novgorod dialect, adopted writing)

- Tatischev 1768, p. 39.

- Tatischev 1768, pp. 39–40.

- Rybakov 1987, pp. 252–253.

- Novgorod First Chronicle 1950, p. 160

- Rybakov 1987, pp. 80 - 81

- Tatischev 1768, p. 40: "Что, безумен, сожалеете о тех, которые себя оборонить не могут! Кую пользу вы от них чаять можете!" (Early Modern Russian adoptation of the Old East Slavic)

- Tatischev 1768, p. 40

- Tatischev 1768, p. 40: "Не вериши и крестити" (Old East Slavic language, Old Novgorod dialect)

- Cited via: Mansikka 2005, p. 88

- Khalyavin 2013, p. 21

- Rybakov 1987, p. 53

- Tatischev 1768, p. 50

- Cited via Petrov 2003, pp. 61–62: "... последния палицы у святого Бориса и Глеба взем митрополит новгородцкии пред собою сожже, и тако преста бесовское то тризнище со оловеными наконечниками тяжкими" (Early Modern Russian, adopted writing)

- Yakushkin 1860, p. 118

- Vasilyev 1999, p. 311

- Miller 1891, pp. 129 - 131

- Cited via: Rybakov 1987, pp. 259 - 260

- Rybakov 1987, p. 559

- Sedov 1953, p. 93

- Sedov 1953, p. 94.

- Sedov 1953, p. 100.

- Rybakov 1987, p. 427

- Sedov 1953, p. 101

- Sedov 1953, p. 96

- Rybakov 1987, p. 256

- Cited via Rybakov 1987, p. 256: "Время сооружения святилища, следует отнести по крайней мере к IX столетию"

- Rybakov 1987, p. 257

- Klein 2004, pp. 152 - 157, 160 - 164

- Konetsky 1995, pp. 80 - 85

- Sedov 1953, pp. 99, 101

- Sedov 1953, p. 99: "Несомненно, это остатки святилища Перуна" (Russian)

- Tatischev 1994, p. 63: "...[Владимир] вскоре повелел строить церкви, и поставлять на местах, где стояли кумиры. И постави церковь святаго Власия на холме, где стоял Перун... (Early Modern Russian)"

- Novgorod Fourth Chronicle 2000, p. 346

- Novgorod Chronicles 1879, p. 325

- Yanin 1984a, p. 119.

- Sedov 2009, p. 30

- The chronicle of the Yuriev Monastery 2008, p. 43

- Stroev 2007, clmn. 106

- Minakov 2013, p. 26

- Minakov 2013, p. 36

- The chronicle of the Yuriev Monastery 2008, p. 70

- Sedov 2009, p. 31

- Sedov 2009, p. 34

- New Testament 2002, p. 278

References

Websites:

- The official webpage of the Peryn Skete. The skete of the Nativity of Our Lady (in Russian). Veliky Novgorod: The Yuriev Monastery. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

Literature:

- Bibikov Michail (2003). "Kogda byla kreşena Rus'? Vglǎd iz Vizantii". In Melnikova, Elena (ed.). Drevnjaja Rus' v svete zarubežnyh istočnikov (in Russian). Moscow: Logos. ISBN 978-5-88439-088-1.

- Herberstein, Sigmund Freiherr von (1852). Notes upon Russia : Being a translation of the earliest account of that country, entitled Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii. Vol. 2 (the original document ed.). London: Hakluyt Society. p. 26.

- Klein, Lev (2004). Voskrešenie Peruna: k rekonstrurtcii vostočnoslavănskogo yazyčestva (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Evrazia. ISBN 978-5-8071-0153-2.

- Mansikka, V. (2005). Religiǎ vostočnyh slavǎn (in Russian). Moscow: The Russian Academy of Science. ISBN 978-5-9208-0238-5.

- Nosov Evgeny [in Russian] (2007). "Peryn". In Yanin, Valentin (ed.). Veliky Novgorod: istoriă i kultura IX-XVII vekov. Enciklopedičesky slovar (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Nestor-Istoria. pp. 379–381. ISBN 978-5-89740-080-5.

- Oleary, Adam (1870). Podrobnoe opisanie putešestviă Golštinskogo posolstva v Moskoviǔ i Persiǔ v 1633, 1636 i 1639, sostavlennoe sekretakёm posolstva Adamom Oleariem. Perevёl s nemeckogo Pavel Barsov (in Russian) (the original Russian translation ed.). Moscow: Imperatorskoe obşestvo istorii i drevnostey Rossiyskih pri Moscovskom universitete. pp. 80–81.

- Petrov, A. (2003). Ot yazychestva k Rusi. Novgorodskie usobicy (k isucheniǔ drevnerusskogo večevogo uklada) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Izdatelstvo Olega Abyshko. ISBN 978-5-89740-080-5.

- Prohorov, A.; Gorkin, A.; Borodulin, V.; et al., eds. (1997). Illŭstrirovanny ėnciklopedičesky slovar (in Russian). Moscow: Naučnoe izdatelsvo "Bolshaă Rossiĭskaă ėnciklopediă". ISBN 978-5-85270-133-6.

- Rybakov, Boris (1987). Yazyčestvo drevney Rusi (in Russian). Moscow: The Academy of sciences of the USSR.

- Sedov, Vladimir (2009). Tserkov Rozhdestva Bogorodicy v Peryni: novgorodskiy variant bašneobraznogo hrama (in Russian). Moscow: Severny Palomnik.

- Sekretar, L.; Sarabyanov, E.; Gordienko, V. (2000). the patriarch, Kirill (ed.). Pravoslavnayâ èntsiklopediyâ. Vol. 14. Moscow: Tserkovno-nauchnyi tsentr "Pravoslavnayâ èntsiklopediyâ". pp. 456–459. ISBN 978-5-89572-007-3.

- Stroev, Pavel (2007). Spiski ierarkhov i nastoăteleĭ monastyreĭ Rossiĭskiă cerkvi (the reprint of the 1877's document ed.). Moscow: Rukopisnye pami︠a︡tniki Drevneĭ Rusi. ISBN 978-5-9551-0072-2.

- Tatischev, Vasili (1994). Sobranie sočineniy v 8 tomax. Istoriă Rossiyskaă s samyh drevneishih vremёn (in Russian). Vol. 2, 3 (the reprint of the 1863's and 1864's document ed.). Moscow: Ladomir. ISBN 978-5-86218-160-9.

- Tatischev, Vasili (1768). Istoriă Rossiyskaă s samyh drevneyshih vremёn (in Russian). Vol. 1 (the original document ed.). Moscow: Imperatorsky Moscovsky Universitet.

- Vasilyev, M. (1999). Yazyčestvo vostočnyh slavăn nakanune kreşeniă Rusi. Religiozno-mifologičeskoe vzaimodeistvie s Iranskim mirom. Yazyčeskaă reforma knăza Vladimira. Moscow: Indrik. ISBN 978-5-85759-087-4.

- Yakushkin, Pavel (1860). Putevye pisma iz Novgorodskoy i Pskovskoi guberniy (in Russian) (the original document ed.). Saint Petersburg: Tipografia torgovogo doma S. Strugovschikova, G. Pohitonova, N. Vodova i K°.

Periodicals:

- Jakobson, Roman (1955). "While Reading Vasmer's Dictionary". WORD. 11 (4): 611–617. doi:10.1080/00437956.1955.11659581.

- Khalyavin, Nikolay (2013). "The christening of Novgorod in pre-revolutionary home historiography" (PDF). Vestnik Udmurtskogo Universiteta. Istoriă i filologiă (in Russian) (3): 21–27.

- Konetsky, Vladimir (1995). "Nekotorye aspekty istočnikovedeniă i interpretacii kompleksa pamătnikov v Peryni pod Novgorodom". Cerkovnaă Arheologiă (in Russian). Saint Peterburg. 1.

- Melnikova, Elena; Petruhin, Vladimir (1986). "Formirovanie seti rannegorodoskih centrov i stanovlenie gosudarstva (Drevnaă Rus' i Skandinavia)". Istoriă SSSR (in Russian) (5): 63–77.

- Miller, Vsevolod (1891). "Materialy dlă istorii bylinnyh sǔzhetov". Etnografičeskoe Obozrenie (in Russian) (4): 118–119.

- Minakov, Arkady (2013). "The Circumstances of the Occurrence and Activity of the "Orthodox Party" in the 1820s". Hristianskoe čtenie (in Russian). 1: 25–38. ISSN 1814-5574.

- Mizeretsky, Ioann (1885). "Rasskazy ob arhimandrite Fotii. Zapisal F. S." Istorychesky Vestnik (in Russian). 21 (9): 557–575.

- Nosov, Evgeny [in Russian] (1987). "New data on Ruyrik Gorodische in Novgorod" (PDF). Fennoscandia Archeologica (IV): 73–85. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Sedov, Vasili (1953). "Drevneslavănskoe yazyčeskoe svătilişe v Peryni". Kratkie Soobşeniă Instituta Istorii Materialnoy Kultury (in Russian) (50): 92–103.

- Yanin, Valentin (1974). "Cerkov Borisa i Gleba v novgorodskom detince (o novgorodskom istočnike zhitiă Aleksandra Nevskogo)". Kultura Srednevekovoy Rusi (in Russian). Leningrad: 91.

- Yanin, Valentin; Aleshkovsky, Mihail (1971). "Proishoždenie Novgoroda (k postanovke problemy)". Istoriă SSSR (in Russian). Moscow-Leningrad. 2: 32–61.

Original documents reprinted:

- New Testament (2002). New king James version (in English and Swedish). Örebro: Gideoniterna.

- Novgorod Chronicles, the miscellanea of reprinted versions (1879). Novgorodskie letopisi (in Old East Slavic). Saint Petersburg: Arheograficheskaă komissiă.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Novgorod First Chronicle, the reprinted version (1950). Novgorodskaă Pervaă Letopis staršego i mladšego izvodov (in Old East Slavic). Moscow - Leningrad: The Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Novgorod Fourth Chronicle, the reprinted version (2000). Novgorodskaă Chetvyortaă Letopis (in Old East Slavic). Vol. IV (Fototip. izd. ed.). Moscow: Yazyki russkoĭ kultury. ISBN 978-5-88766-063-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - The chronicle of the Yuriev Monastery, the reprinted version (2008). Letopis Yurieva monastyră (in Early Modern Russian). Saint Petersburg: Aleteă.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - The Primary Chronicle, the reprinted version (1908). Povest' vremennyh let po Ipatyevskomy spisky (The Primary Chronicle) (in Old East Slavic). Vol. 2. Saint Petersburg. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - The Saga about Sloven and Rus and the city Slovensk, the reprinted version (1977). Skazanie o Slovene i Ruse i gorode Slovenske (in Early Modern Russian). Vol. 31 (Polnoe sobranie russkih letopisey ed.). Leningrad: The Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Archived from the original on 2007-06-05.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Yanin, Valentin, ed. (1984a). Opis' Novgoroda 1617 goda v 1 častăh [The inventory of Novgorod in 1617] (in Early Modern Russian). Vol. 1 (reprint ed.). Moscow: The Academy of Sciences of the USSR. pp. 1–175.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Yanin, Valentin, ed. (1984b). Opis' Novgoroda 1617 goda v 2 častăh [The inventory of Novgorod in 1617] (in Early Modern Russian). Vol. 2 (reprint ed.). Moscow: The Academy of Sciences of the USSR. pp. 176–370.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)