Christianity

Christianity (/krɪstʃiˈænɪti/) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.4 billion followers representing one-third of the global population.[1][2] Its adherents, known as Christians, are estimated to make up a majority of the population in 157 countries and territories.[3] They believe that Jesus is the Son of God, whose coming as the Messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible (called the Old Testament in Christianity) and chronicled in the New Testament.[4]

| Christianity | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Universal religion |

| Classification | Abrahamic |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Theology | Monotheistic |

| Region | Worldwide |

| Language | Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek and Latin |

| Territory | Christendom |

| Founder | Jesus |

| Origin | 1st century AD Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Separated from | Second Temple Judaism |

| Number of followers | c. 2.4 billion (referred to as Christians) |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, and doctrinally diverse concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology. The creeds of various Christian denominations generally hold in common Jesus as the Son of God—the Logos incarnated—who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but rose from the dead for the salvation of humankind; and referred to as the gospel, meaning the "good news". The four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John describe Jesus's life and teachings, with the Old Testament as the gospels' respected background.

Christianity began in the 1st century after the birth of Jesus as a Judaic sect with Hellenistic influence, in the Roman province of Judea. The disciples of Jesus spread their faith around the Eastern Mediterranean area, despite significant persecution. The inclusion of Gentiles led Christianity to slowly separate from Judaism (2nd century). Emperor Constantine the Great decriminalized Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan (313), later convening the Council of Nicaea (325) where Early Christianity was consolidated into what would become the State church of the Roman Empire (380). The Church of the East and Oriental Orthodoxy both split over differences in Christology (5th century),[5] while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church separated in the East–West Schism (1054). Protestantism split into numerous denominations from the Catholic Church in the Reformation era (16th century). Following the Age of Discovery (15th–17th century), Christianity expanded throughout the world via missionary work, extensive trade[6] and colonialism. Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, particularly in Europe from late antiquity and the Middle Ages.[7][8][9][10]

The six major branches of Christianity are Roman Catholicism (1.3 billion people), Protestantism (800 million),[note 1] Eastern Orthodoxy (220 million), Oriental Orthodoxy (60 million),[12][13] Restorationism (35 million),[14] and the Church of the East (600 thousand). Smaller church communities number in the thousands despite efforts toward unity (ecumenism).[15] In the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion even with a decline in adherence, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian.[16][17] Christianity is growing in Africa and Asia, the world's most populous continents.[16] Christians remain greatly persecuted in many regions of the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia, and South Asia.[18][19]

Etymology

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as 'The Way' (Koinē Greek: τῆς ὁδοῦ, romanized: tês hodoû), probably coming from Isaiah 40:3, "prepare the way of the Lord".[note 2] According to Acts 11:26, the term "Christian" (Χρῑστῐᾱνός, Khrīstiānós), meaning "followers of Christ" in reference to Jesus's disciples, was first used in the city of Antioch by the non-Jewish inhabitants there.[25] The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity/Christianism" (Χρῑστῐᾱνισμός, Khrīstiānismós) was by Ignatius of Antioch around 100 AD.[26]

Beliefs

While Christians worldwide share basic convictions, there are differences of interpretations and opinions of the Bible and sacred traditions on which Christianity is based.[27]

Creeds

Concise doctrinal statements or confessions of religious beliefs are known as creeds. They began as baptismal formulae and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries to become statements of faith. "Jesus is Lord" is the earliest creed of Christianity and continues to be used, as with the World Council of Churches.[28]

The Apostles' Creed is the most widely accepted statement of the articles of Christian faith. It is used by a number of Christian denominations for both liturgical and catechetical purposes, most visibly by liturgical churches of Western Christian tradition, including the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and Western Rite Orthodoxy. It is also used by Presbyterians, Methodists, and Congregationalists.

This particular creed was developed between the 2nd and 9th centuries. Its central doctrines are those of the Trinity and God the Creator. Each of the doctrines found in this creed can be traced to statements current in the apostolic period. The creed was apparently used as a summary of Christian doctrine for baptismal candidates in the churches of Rome.[29] Its points include:

- Belief in God the Father, Jesus Christ as the Son of God, and the Holy Spirit

- The death, descent into hell, resurrection and ascension of Christ

- The holiness of the Church and the communion of saints

- Christ's second coming, the Day of Judgement and salvation of the faithful

The Nicene Creed was formulated, largely in response to Arianism, at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively,[30][31] and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the First Council of Ephesus in 431.[32]

The Chalcedonian Definition, or Creed of Chalcedon, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451,[33] though rejected by the Oriental Orthodox,[34] taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, and that both natures, while perfect in themselves, are nevertheless also perfectly united into one person.[35]

The Athanasian Creed, received in the Western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance".[36]

Most Christians (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Protestant alike) accept the use of creeds and subscribe to at least one of the creeds mentioned above.[37]

Certain Evangelical Protestants, though not all of them, reject creeds as definitive statements of faith, even while agreeing with some or all of the substance of the creeds. Also rejecting creeds are groups with roots in the Restoration Movement, such as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), the Evangelical Christian Church in Canada, and the Churches of Christ.[38][39]: 14–15 [40]: 123

Jesus

The central tenet of Christianity is the belief in Jesus as the Son of God and the Messiah (Christ).[41] Christians believe that Jesus, as the Messiah, was anointed by God as savior of humanity and hold that Jesus's coming was the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. The core Christian belief is that through belief in and acceptance of the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God, and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.[42]

While there have been many theological disputes over the nature of Jesus over the earliest centuries of Christian history, generally, Christians believe that Jesus is God incarnate and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human, suffered the pains and temptations of a mortal man, but did not sin. As fully God, he rose to life again. According to the New Testament, he rose from the dead,[43] ascended to heaven, is seated at the right hand of the Father,[44] and will ultimately return[45] to fulfill the rest of the Messianic prophecy, including the resurrection of the dead, the Last Judgment, and the final establishment of the Kingdom of God.

According to the canonical gospels of Matthew and Luke, Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born from the Virgin Mary. Little of Jesus's childhood is recorded in the canonical gospels, although infancy gospels were popular in antiquity.[46] In comparison, his adulthood, especially the week before his death, is well documented in the gospels contained within the New Testament, because that part of his life is believed to be most important. The biblical accounts of Jesus's ministry include: his baptism, miracles, preaching, teaching, and deeds.

Death and resurrection

Christians consider the resurrection of Jesus to be the cornerstone of their faith (see 1 Corinthians 15) and the most important event in history.[47] Among Christian beliefs, the death and resurrection of Jesus are two core events on which much of Christian doctrine and theology is based.[48] According to the New Testament, Jesus was crucified, died a physical death, was buried within a tomb, and rose from the dead three days later.[49]

The New Testament mentions several post-resurrection appearances of Jesus on different occasions to his twelve apostles and disciples, including "more than five hundred brethren at once",[50] before Jesus's ascension to heaven. Jesus's death and resurrection are commemorated by Christians in all worship services, with special emphasis during Holy Week, which includes Good Friday and Easter Sunday.

The death and resurrection of Jesus are usually considered the most important events in Christian theology, partly because they demonstrate that Jesus has power over life and death and therefore has the authority and power to give people eternal life.[51]

Christian churches accept and teach the New Testament account of the resurrection of Jesus with very few exceptions.[52] Some modern scholars use the belief of Jesus's followers in the resurrection as a point of departure for establishing the continuity of the historical Jesus and the proclamation of the early church.[53] Some liberal Christians do not accept a literal bodily resurrection,[54][55] seeing the story as richly symbolic and spiritually nourishing myth. Arguments over death and resurrection claims occur at many religious debates and interfaith dialogues.[56] Paul the Apostle, an early Christian convert and missionary, wrote, "If Christ was not raised, then all our preaching is useless, and your trust in God is useless".[57][58]

Salvation

"For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life".

— John 3:16, NIV[59]

_-_The_Law_and_the_Gospel.jpg.webp)

Paul the Apostle, like Jews and Roman pagans of his time, believed that sacrifice can bring about new kinship ties, purity, and eternal life.[60] For Paul, the necessary sacrifice was the death of Jesus: Gentiles who are "Christ's" are, like Israel, descendants of Abraham and "heirs according to the promise"[61][62] The God who raised Jesus from the dead would also give new life to the "mortal bodies" of Gentile Christians, who had become with Israel, the "children of God", and were therefore no longer "in the flesh".[63][60]

Modern Christian churches tend to be much more concerned with how humanity can be saved from a universal condition of sin and death than the question of how both Jews and Gentiles can be in God's family. According to Eastern Orthodox theology, based upon their understanding of the atonement as put forward by Irenaeus' recapitulation theory, Jesus' death is a ransom. This restores the relation with God, who is loving and reaches out to humanity, and offers the possibility of theosis c.q. divinization, becoming the kind of humans God wants humanity to be. According to Catholic doctrine, Jesus' death satisfies the wrath of God, aroused by the offense to God's honor caused by human's sinfulness. The Catholic Church teaches that salvation does not occur without faithfulness on the part of Christians; converts must live in accordance with principles of love and ordinarily must be baptized.[64] In Protestant theology, Jesus' death is regarded as a substitutionary penalty carried by Jesus, for the debt that has to be paid by humankind when it broke God's moral law.[65]

Christians differ in their views on the extent to which individuals' salvation is pre-ordained by God. Reformed theology places distinctive emphasis on grace by teaching that individuals are completely incapable of self-redemption, but that sanctifying grace is irresistible.[66] In contrast Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Arminian Protestants believe that the exercise of free will is necessary to have faith in Jesus.[67]

Trinity

Trinity refers to the teaching that the one God[69] comprises three distinct, eternally co-existing persons: the Father, the Son (incarnate in Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. Together, these three persons are sometimes called the Godhead,[70][71][72] although there is no single term in use in Scripture to denote the unified Godhead.[73] In the words of the Athanasian Creed, an early statement of Christian belief, "the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God".[74] They are distinct from another: the Father has no source, the Son is begotten of the Father, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. Though distinct, the three persons cannot be divided from one another in being or in operation. While some Christians also believe that God appeared as the Father in the Old Testament, it is agreed that he appeared as the Son in the New Testament and will still continue to manifest as the Holy Spirit in the present. But still, God still existed as three persons in each of these times.[75] However, traditionally there is a belief that it was the Son who appeared in the Old Testament because, for example, when the Trinity is depicted in art, the Son typically has the distinctive appearance, a cruciform halo identifying Christ, and in depictions of the Garden of Eden, this looks forward to an Incarnation yet to occur. In some Early Christian sarcophagi, the Logos is distinguished with a beard, "which allows him to appear ancient, even pre-existent".[76]

The Trinity is an essential doctrine of mainstream Christianity. From earlier than the times of the Nicene Creed (325) Christianity advocated[77] the triune mystery-nature of God as a normative profession of faith. According to Roger E. Olson and Christopher Hall, through prayer, meditation, study and practice, the Christian community concluded "that God must exist as both a unity and trinity", codifying this in ecumenical council at the end of the 4th century.[78][79]

According to this doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God (see Perichoresis). The distinction lies in their relations, the Father being unbegotten; the Son being begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and (in Western Christian theology) from the Son. Regardless of this apparent difference, the three "persons" are each eternal and omnipotent. Other Christian religions including Unitarian Universalism, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Mormonism, do not share those views on the Trinity.

The Greek word trias[80][note 3] is first seen in this sense in the works of Theophilus of Antioch; his text reads: "of the Trinity, of God, and of His Word, and of His Wisdom".[84] The term may have been in use before this time; its Latin equivalent,[note 3] trinitas,[82] appears afterwards with an explicit reference to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in Tertullian.[85][86] In the following century, the word was in general use. It is found in many passages of Origen.[87]

Trinitarianism

Trinitarianism denotes Christians who believe in the concept of the Trinity. Almost all Christian denominations and churches hold Trinitarian beliefs. Although the words "Trinity" and "Triune" do not appear in the Bible, beginning in the 3rd century theologians developed the term and concept to facilitate apprehension of the New Testament teachings of God as being Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Since that time, Christian theologians have been careful to emphasize that Trinity does not imply that there are three gods (the antitrinitarian heresy of Tritheism), nor that each hypostasis of the Trinity is one-third of an infinite God (partialism), nor that the Son and the Holy Spirit are beings created by and subordinate to the Father (Arianism). Rather, the Trinity is defined as one God in three persons.[88]

Nontrinitarianism

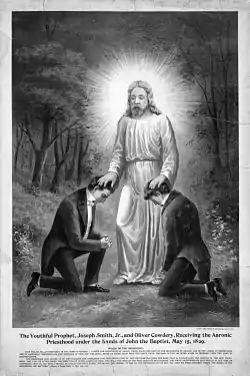

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to theology that rejects the doctrine of the Trinity. Various nontrinitarian views, such as adoptionism or modalism, existed in early Christianity, leading to disputes about Christology.[89] Nontrinitarianism reappeared in the Gnosticism of the Cathars between the 11th and 13th centuries, among groups with Unitarian theology in the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century,[90] in the 18th-century Enlightenment, among Restorationist groups arising during the Second Great Awakening of the 19th century, and most recently, in Oneness Pentecostal churches.

Eschatology

The end of things, whether the end of an individual life, the end of the age, or the end of the world, broadly speaking, is Christian eschatology; the study of the destiny of humans as it is revealed in the Bible. The major issues in Christian eschatology are the Tribulation, death and the afterlife, (mainly for Evangelical groups) the Millennium and the following Rapture, the Second Coming of Jesus, Resurrection of the Dead, Heaven, (for liturgical branches) Purgatory, and Hell, the Last Judgment, the end of the world, and the New Heavens and New Earth.

Christians believe that the second coming of Christ will occur at the end of time, after a period of severe persecution (the Great Tribulation). All who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgment. Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[91][92]

Death and afterlife

Most Christians believe that human beings experience divine judgment and are rewarded either with eternal life or eternal damnation. This includes the general judgement at the resurrection of the dead as well as the belief (held by Catholics,[93][94] Orthodox[95][96] and most Protestants) in a judgment particular to the individual soul upon physical death.

In the Catholic branch of Christianity, those who die in a state of grace, i.e., without any mortal sin separating them from God, but are still imperfectly purified from the effects of sin, undergo purification through the intermediate state of purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into God's presence.[97] Those who have attained this goal are called saints (Latin sanctus, "holy").[98]

Some Christian groups, such as Seventh-day Adventists, hold to mortalism, the belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal, and is unconscious during the intermediate state between bodily death and resurrection. These Christians also hold to Annihilationism, the belief that subsequent to the final judgement, the wicked will cease to exist rather than suffer everlasting torment. Jehovah's Witnesses hold to a similar view.[99]

Practices

.jpg.webp)

Depending on the specific denomination of Christianity, practices may include baptism, the Eucharist (Holy Communion or the Lord's Supper), prayer (including the Lord's Prayer), confession, confirmation, burial rites, marriage rites and the religious education of children. Most denominations have ordained clergy who lead regular communal worship services.[101]

Christian rites, rituals, and ceremonies are not celebrated in one single sacred language. Many ritualistic Christian churches make a distinction between sacred language, liturgical language and vernacular language. The three important languages in the early Christian era were: Latin, Greek and Syriac.[102][103][104]

Communal worship

Services of worship typically follow a pattern or form known as liturgy.[note 4] Justin Martyr described 2nd-century Christian liturgy in his First Apology (c. 150) to Emperor Antoninus Pius, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.[106]

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship typically on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the gospels.[note 5][107] Instruction is given based on these readings, in the form of a sermon or homily. There are a variety of congregational prayers, including thanksgiving, confession, and intercession, which occur throughout the service and take a variety of forms including recited, responsive, silent, or sung.[101] Psalms, hymns, worship songs, and other church music may be sung.[108][109] Services can be varied for special events like significant feast days.[110]

Nearly all forms of worship incorporate the Eucharist, which consists of a meal. It is reenacted in accordance with Jesus' instruction at the Last Supper that his followers do in remembrance of him as when he gave his disciples bread, saying, "This is my body", and gave them wine saying, "This is my blood".[111] In the early church, Christians and those yet to complete initiation would separate for the Eucharistic part of the service.[112] Some denominations such as Confessional Lutheran churches continue to practice 'closed communion'.[113] They offer communion to those who are already united in that denomination or sometimes individual church. Catholics further restrict participation to their members who are not in a state of mortal sin.[114] Many other churches, such as Anglican Communion and the Methodist Churches (such as the Free Methodist Church and United Methodist Church), practice 'open communion' since they view communion as a means to unity, rather than an end, and invite all believing Christians to participate.[115][116][117]

Sacraments or ordinances

And this food is called among us Eukharistia [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

In Christian belief and practice, a sacrament is a rite, instituted by Christ, that confers grace, constituting a sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word sacramentum, which was used to translate the Greek word for mystery. Views concerning both which rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament, vary among Christian denominations and traditions.[118]

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are Baptism and the Eucharist; however, the majority of Christians also recognize five additional sacraments: Confirmation (Chrismation in the Eastern tradition), Holy Orders (or ordination), Penance (or Confession), Anointing of the Sick, and Matrimony (see Christian views on marriage).[118]

Taken together, these are the Seven Sacraments as recognized by churches in the High Church tradition—notably Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Independent Catholic, Old Catholic, many Anglicans, and some Lutherans. Most other denominations and traditions typically affirm only Baptism and Eucharist as sacraments, while some Protestant groups, such as the Quakers, reject sacramental theology.[118] Certain denominations of Christianity, such as Anabaptists, use the term "ordinances" to refer to rites instituted by Jesus for Christians to observe.[119] Seven ordinances have been taught in many Conservative Mennonite Anabaptist churches, which include "baptism, communion, footwashing, marriage, anointing with oil, the holy kiss, and the prayer covering".[100]

In addition to this, the Church of the East has two additional sacraments in place of the traditional sacraments of Matrimony and the Anointing of the Sick. These include Holy Leaven (Melka) and the sign of the cross.[120]

A penitent confessing his sins in a Ukrainian Catholic church

A penitent confessing his sins in a Ukrainian Catholic church

Confirmation being administered in an Anglican church

Confirmation being administered in an Anglican church Ordination of a priest in the Eastern Orthodox tradition

Ordination of a priest in the Eastern Orthodox tradition

Service of the Sacrament of Holy Unction served on Great and Holy Wednesday

Service of the Sacrament of Holy Unction served on Great and Holy Wednesday

Liturgical calendar

Catholics, Eastern Christians, Lutherans, Anglicans and other traditional Protestant communities frame worship around the liturgical year.[121] The liturgical cycle divides the year into a series of seasons, each with their theological emphases, and modes of prayer, which can be signified by different ways of decorating churches, colors of paraments and vestments for clergy,[122] scriptural readings, themes for preaching and even different traditions and practices often observed personally or in the home.

Western Christian liturgical calendars are based on the cycle of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church,[122] and Eastern Christians use analogous calendars based on the cycle of their respective rites. Calendars set aside holy days, such as solemnities which commemorate an event in the life of Jesus, Mary, or the saints, and periods of fasting, such as Lent and other pious events such as memoria, or lesser festivals commemorating saints. Christian groups that do not follow a liturgical tradition often retain certain celebrations, such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost: these are the celebrations of Christ's birth, resurrection, and the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Church, respectively. A few denominations such as Quaker Christians make no use of a liturgical calendar.[123]

Symbols

Most Christian denominations have not generally practiced aniconism,[124] the avoidance or prohibition of devotional images, even if early Jewish Christians, invoking the Decalogue's prohibition of idolatry, avoided figures in their symbols.[125]

The cross, today one of the most widely recognized symbols, was used by Christians from the earliest times.[126][127] Tertullian, in his book De Corona, tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace the sign of the cross on their foreheads.[128] Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix did not appear in use until the 5th century.[129]

Among the earliest Christian symbols, that of the fish or Ichthys seems to have ranked first in importance, as seen on monumental sources such as tombs from the first decades of the 2nd century.[130] Its popularity seemingly arose from the Greek word ichthys (fish) forming an acrostic for the Greek phrase Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ),[note 6] (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior), a concise summary of Christian faith.[130]

Other major Christian symbols include the chi-rho monogram, the dove and olive branch (symbolic of the Holy Spirit), the sacrificial lamb (representing Christ's sacrifice), the vine (symbolizing the connection of the Christian with Christ) and many others. These all derive from passages of the New Testament.[129]

Baptism

.jpg.webp)

Baptism is the ritual act, with the use of water, by which a person is admitted to membership of the Church. Beliefs on baptism vary among denominations. Differences occur firstly on whether the act has any spiritual significance. Some, such as the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, as well as Lutherans and Anglicans, hold to the doctrine of baptismal regeneration, which affirms that baptism creates or strengthens a person's faith, and is intimately linked to salvation. Baptists and Plymouth Brethren view baptism as a purely symbolic act, an external public declaration of the inward change which has taken place in the person, but not as spiritually efficacious. Secondly, there are differences of opinion on the methodology (or mode) of the act. These modes are: by immersion; if immersion is total, by submersion; by affusion (pouring); and by aspersion (sprinkling). Those who hold the first view may also adhere to the tradition of infant baptism;[131][132][133][134] the Orthodox Churches all practice infant baptism and always baptize by total immersion repeated three times in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.[135][136] The Lutheran Church and the Catholic Church also practice infant baptism,[137][138][139] usually by affusion, and using the Trinitarian formula.[140] Anabaptist Christians practice believer's baptism, in which an adult chooses to receive the ordinance after making a decision to follow Jesus.[141] Anabaptist denominations such as the Mennonites, Amish and Hutterites use pouring as the mode to administer believer's baptism, whereas Anabaptists of the Schwarzenau Brethren and River Brethren traditions baptize by immersion.[142][143][144][145]

Prayer

"... ‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us today our daily bread. Forgive us our debts, as we also forgive our debtors. Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil’".

— The Lord's Prayer, Matthew 6:9–13, EHV[146]

In the Gospel of Saint Matthew, Jesus taught the Lord's Prayer, which has been seen as a model for Christian prayer.[147] The injunction for Christians to pray the Lord's prayer thrice daily was given in the Didache and came to be recited by Christians at 9 am, 12 pm, and 3 pm.[148][149]

In the second century Apostolic Tradition, Hippolytus instructed Christians to pray at seven fixed prayer times: "on rising, at the lighting of the evening lamp, at bedtime, at midnight" and "the third, sixth and ninth hours of the day, being hours associated with Christ's Passion".[150] Prayer positions, including kneeling, standing, and prostrations have been used for these seven fixed prayer times since the days of the early Church.[151] Breviaries such as the Shehimo and Agpeya are used by Oriental Orthodox Christians to pray these canonical hours while facing in the eastward direction of prayer.[152][153]

The Apostolic Tradition directed that the sign of the cross be used by Christians during the minor exorcism of baptism, during ablutions before praying at fixed prayer times, and in times of temptation.[154]

Intercessory prayer is prayer offered for the benefit of other people. There are many intercessory prayers recorded in the Bible, including prayers of the Apostle Peter on behalf of sick persons[155] and by prophets of the Old Testament in favor of other people.[156] In the Epistle of James, no distinction is made between the intercessory prayer offered by ordinary believers and the prominent Old Testament prophet Elijah.[157] The effectiveness of prayer in Christianity derives from the power of God rather than the status of the one praying.[158]

The ancient church, in both Eastern and Western Christianity, developed a tradition of asking for the intercession of (deceased) saints, and this remains the practice of most Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic, and some Lutheran and Anglican churches.[159] Apart from certain sectors within the latter two denominations, other Churches of the Protestant Reformation, however, rejected prayer to the saints, largely on the basis of the sole mediatorship of Christ.[160] The reformer Huldrych Zwingli admitted that he had offered prayers to the saints until his reading of the Bible convinced him that this was idolatrous.[161]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church: "Prayer is the raising of one's mind and heart to God or the requesting of good things from God".[162] The Book of Common Prayer in the Anglican tradition is a guide which provides a set order for services, containing set prayers, scripture readings, and hymns or sung Psalms.[163] Frequently in Western Christianity, when praying, the hands are placed palms together and forward as in the feudal commendation ceremony. At other times the older orans posture may be used, with palms up and elbows in.

Scriptures

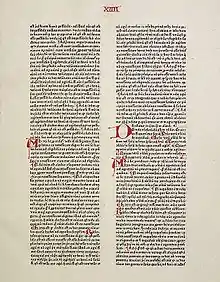

Christianity, like other religions, has adherents whose beliefs and biblical interpretations vary. Christianity regards the biblical canon, the Old Testament and the New Testament, as the inspired word of God. The traditional view of inspiration is that God worked through human authors so that what they produced was what God wished to communicate. The Greek word referring to inspiration in 2 Timothy 3:16 is theopneustos, which literally means "God-breathed".[164]

Some believe that divine inspiration makes present Bibles inerrant. Others claim inerrancy for the Bible in its original manuscripts, although none of those are extant. Still others maintain that only a particular translation is inerrant, such as the King James Version.[165][166][167] Another closely related view is biblical infallibility or limited inerrancy, which affirms that the Bible is free of error as a guide to salvation, but may include errors on matters such as history, geography, or science.

The canon of the Old Testament accepted by Protestant churches, which is only the Tanakh (the canon of the Hebrew Bible), is shorter than that accepted by the Orthodox and Catholic churches which also include the deuterocanonical books which appear in the Septuagint, the Orthodox canon being slightly larger than the Catholic;[168] Protestants regard the latter as apocryphal, important historical documents which help to inform the understanding of words, grammar, and syntax used in the historical period of their conception. Some versions of the Bible include a separate Apocrypha section between the Old Testament and the New Testament.[169] The New Testament, originally written in Koine Greek, contains 27 books which are agreed upon by all major churches.

Some denominations have additional canonical holy scriptures beyond the Bible, including the standard works of the Latter Day Saints movement and Divine Principle in the Unification Church.[170]

Catholic interpretation

In antiquity, two schools of exegesis developed in Alexandria and Antioch. The Alexandrian interpretation, exemplified by Origen, tended to read Scripture allegorically, while the Antiochene interpretation adhered to the literal sense, holding that other meanings (called theoria) could only be accepted if based on the literal meaning.[171]

Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of scripture: the literal and the spiritual.[172]

The literal sense of understanding scripture is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture. The spiritual sense is further subdivided into:

- The allegorical sense, which includes typology. An example would be the parting of the Red Sea being understood as a "type" (sign) of baptism.[173]

- The moral sense, which understands the scripture to contain some ethical teaching.

- The anagogical sense, which applies to eschatology, eternity and the consummation of the world.

Regarding exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation, Catholic theology holds:

- The injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal[174][175]

- That the historicity of the Gospels must be absolutely and constantly held[176]

- That scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church"[177] and

- That "the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome".[178]

Qualities of Scripture

Many Protestant Christians, such as Lutherans and the Reformed, believe in the doctrine of sola scriptura—that the Bible is a self-sufficient revelation, the final authority on all Christian doctrine, and revealed all truth necessary for salvation;[179][180] other Protestant Christians, such as Methodists and Anglicans, affirm the doctrine of prima scriptura which teaches that Scripture is the primary source for Christian doctrine, but that "tradition, experience, and reason" can nurture the Christian religion as long as they are in harmony with the Bible.[179][181] Protestants characteristically believe that ordinary believers may reach an adequate understanding of Scripture because Scripture itself is clear in its meaning (or "perspicuous"). Martin Luther believed that without God's help, Scripture would be "enveloped in darkness".[182] He advocated for "one definite and simple understanding of Scripture".[182] John Calvin wrote, "all who refuse not to follow the Holy Spirit as their guide, find in the Scripture a clear light".[183] Related to this is "efficacy", that Scripture is able to lead people to faith; and "sufficiency", that the Scriptures contain everything that one needs to know to obtain salvation and to live a Christian life.[184]

Original intended meaning of Scripture

Protestants stress the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture, the historical-grammatical method.[185] The historical-grammatical method or grammatico-historical method is an effort in Biblical hermeneutics to find the intended original meaning in the text.[186] This original intended meaning of the text is drawn out through examination of the passage in light of the grammatical and syntactical aspects, the historical background, the literary genre, as well as theological (canonical) considerations.[187] The historical-grammatical method distinguishes between the one original meaning and the significance of the text. The significance of the text includes the ensuing use of the text or application. The original passage is seen as having only a single meaning or sense. As Milton S. Terry said: "A fundamental principle in grammatico-historical exposition is that the words and sentences can have but one significance in one and the same connection. The moment we neglect this principle we drift out upon a sea of uncertainty and conjecture".[188] Technically speaking, the grammatical-historical method of interpretation is distinct from the determination of the passage's significance in light of that interpretation. Taken together, both define the term (Biblical) hermeneutics.[186] Some Protestant interpreters make use of typology.[189]

History

Early Christianity

Apostolic Age

Christianity developed during the 1st century AD as a Jewish Christian sect with Hellenistic influence[190] of Second Temple Judaism.[191][192] An early Jewish Christian community was founded in Jerusalem under the leadership of the Pillars of the Church, namely James the Just, the brother of Jesus, Peter, and John.[193]

Jewish Christianity soon attracted Gentile God-fearers, posing a problem for its Jewish religious outlook, which insisted on close observance of the Jewish commandments. Paul the Apostle solved this by insisting that salvation by faith in Christ, and participation in his death and resurrection by their baptism, sufficed.[194] At first he persecuted the early Christians, but after a conversion experience he preached to the gentiles, and is regarded as having had a formative effect on the emerging Christian identity as separate from Judaism. Eventually, his departure from Jewish customs would result in the establishment of Christianity as an independent religion.[195]

Ante-Nicene period

This formative period was followed by the early bishops, whom Christians consider the successors of Christ's apostles. From the year 150, Christian teachers began to produce theological and apologetic works aimed at defending the faith. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and the study of them is called patristics. Notable early Fathers include Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria and Origen.

Persecution of Christians occurred intermittently and on a small scale by both Jewish and Roman authorities, with Roman action starting at the time of the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. Examples of early executions under Jewish authority reported in the New Testament include the deaths of Saint Stephen[196] and James, son of Zebedee.[197] The Decian persecution was the first empire-wide conflict,[198] when the edict of Decius in 250 AD required everyone in the Roman Empire (except Jews) to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods. The Diocletianic Persecution beginning in 303 AD was also particularly severe. Roman persecution ended in 313 AD with the Edict of Milan.

While Proto-orthodox Christianity was becoming dominant, heterodox sects also existed at the same time, which held radically different beliefs. Gnostic Christianity developed a duotheistic doctrine based on illusion and enlightenment rather than forgiveness of sin. With only a few scriptures overlapping with the developing orthodox canon, most Gnostic texts and Gnostic gospels were eventually considered heretical and suppressed by mainstream Christians. A gradual splitting off of Gentile Christianity left Jewish Christians continuing to follow the Law of Moses, including practices such as circumcision. By the fifth century, they and the Jewish–Christian gospels would be largely suppressed by the dominant sects in both Judaism and Christianity.

Spread and acceptance in Roman Empire

Christianity spread to Aramaic-speaking peoples along the Mediterranean coast and also to the inland parts of the Roman Empire and beyond that into the Parthian Empire and the later Sasanian Empire, including Mesopotamia, which was dominated at different times and to varying extents by these empires.[200] The presence of Christianity in Africa began in the middle of the 1st century in Egypt and by the end of the 2nd century in the region around Carthage. Mark the Evangelist is claimed to have started the Church of Alexandria in about 43 AD; various later churches claim this as their own legacy, including the Coptic Orthodox Church.[201][202][203] Important Africans who influenced the early development of Christianity include Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius, and Augustine of Hippo.

King Tiridates III made Christianity the state religion in Armenia between 301 and 314,[204][205][206] thus Armenia became the first officially Christian state. It was not an entirely new religion in Armenia, having penetrated into the country from at least the third century, but it may have been present even earlier.[207]

Constantine I was exposed to Christianity in his youth, and throughout his life his support for the religion grew, culminating in baptism on his deathbed.[208] During his reign, state-sanctioned persecution of Christians was ended with the Edict of Toleration in 311 and the Edict of Milan in 313. At that point, Christianity was still a minority belief, comprising perhaps only 5% of the Roman population.[209] Influenced by his adviser Mardonius, Constantine's nephew Julian unsuccessfully tried to suppress Christianity.[210] On 27 February 380, Theodosius I, Gratian, and Valentinian II established Nicene Christianity as the State church of the Roman Empire.[211] As soon as it became connected to the state, Christianity grew wealthy; the Church solicited donations from the rich and could now own land.[212]

Constantine was also instrumental in the convocation of the First Council of Nicaea in 325, which sought to address Arianism and formulated the Nicene Creed, which is still used by in Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and many other Protestant churches.[213][37] Nicaea was the first of a series of ecumenical councils, which formally defined critical elements of the theology of the Church, notably concerning Christology.[214] The Church of the East did not accept the third and following ecumenical councils and is still separate today by its successors (Assyrian Church of the East).

In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the Byzantine Empire was one of the peaks in Christian history and Christian civilization,[215] and Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in size, wealth, and culture.[216] There was a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy, as well as an increase in literary output in vernacular Greek.[217] Byzantine art and literature held a preeminent place in Europe, and the cultural impact of Byzantine art on the West during this period was enormous and of long-lasting significance.[218] The later rise of Islam in North Africa reduced the size and numbers of Christian congregations, leaving in large numbers only the Coptic Church in Egypt, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church in the Horn of Africa and the Nubian Church in the Sudan (Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia).

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the West, the papacy became a political player, first visible in Pope Leo's diplomatic dealings with Huns and Vandals.[219] The church also entered into a long period of missionary activity and expansion among the various tribes. While Arianists instituted the death penalty for practicing pagans (see the Massacre of Verden, for example), what would later become Catholicism also spread among the Hungarians, the Germanic,[219] the Celtic, the Baltic and some Slavic peoples.

Around 500, Christianity was thoroughly integrated into Byzantine and Kingdom of Italy culture[220] and Benedict of Nursia set out his Monastic Rule, establishing a system of regulations for the foundation and running of monasteries.[219] Monasticism became a powerful force throughout Europe,[219] and gave rise to many early centers of learning, most famously in Ireland, Scotland, and Gaul, contributing to the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century.

In the 7th century, Muslims conquered Syria (including Jerusalem), North Africa, and Spain, converting some of the Christian population to Islam, and placing the rest under a separate legal status. Part of the Muslims' success was due to the exhaustion of the Byzantine Empire in its decades long conflict with Persia.[221] Beginning in the 8th century, with the rise of Carolingian leaders, the Papacy sought greater political support in the Frankish Kingdom.[222]

The Middle Ages brought about major changes within the church. Pope Gregory the Great dramatically reformed the ecclesiastical structure and administration.[223] In the early 8th century, iconoclasm became a divisive issue, when it was sponsored by the Byzantine emperors. The Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (787) finally pronounced in favor of icons.[224] In the early 10th century, Western Christian monasticism was further rejuvenated through the leadership of the great Benedictine monastery of Cluny.[225]

High and Late Middle Ages

In the West, from the 11th century onward, some older cathedral schools became universities (see, for example, University of Oxford, University of Paris and University of Bologna). Previously, higher education had been the domain of Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools (Scholae monasticae), led by monks and nuns. Evidence of such schools dates back to the 6th century AD.[226] These new universities expanded the curriculum to include academic programs for clerics, lawyers, civil servants, and physicians.[227] The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting.[228][229][230]

Accompanying the rise of the "new towns" throughout Europe, mendicant orders were founded, bringing the consecrated religious life out of the monastery and into the new urban setting. The two principal mendicant movements were the Franciscans[231] and the Dominicans,[232] founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic, respectively. Both orders made significant contributions to the development of the great universities of Europe. Another new order was the Cistercians, whose large, isolated monasteries spearheaded the settlement of former wilderness areas. In this period, church building and ecclesiastical architecture reached new heights, culminating in the orders of Romanesque and Gothic architecture and the building of the great European cathedrals.[233]

Christian nationalism emerged during this era in which Christians felt the impulse to recover lands in which Christianity had historically flourished.[234] From 1095 under the pontificate of Urban II, the First Crusade was launched.[235] These were a series of military campaigns in the Holy Land and elsewhere, initiated in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I for aid against Turkish expansion. The Crusades ultimately failed to stifle Islamic aggression and even contributed to Christian enmity with the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.[236]

The Christian Church experienced internal conflict between the 7th and 13th centuries that resulted in a schism between the Latin Church of Western Christianity branch, the now-Catholic Church, and an Eastern, largely Greek, branch (the Eastern Orthodox Church). The two sides disagreed on a number of administrative, liturgical and doctrinal issues, most prominently Eastern Orthodox opposition to papal supremacy.[237][238] The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) attempted to reunite the churches, but in both cases, the Eastern Orthodox refused to implement the decisions, and the two principal churches remain in schism to the present day. However, the Catholic Church has achieved union with various smaller eastern churches.

In the thirteenth century, a new emphasis on Jesus' suffering, exemplified by the Franciscans' preaching, had the consequence of turning worshippers' attention towards Jews, on whom Christians had placed the blame for Jesus' death. Christianity's limited tolerance of Jews was not new—Augustine of Hippo said that Jews should not be allowed to enjoy the citizenship that Christians took for granted—but the growing antipathy towards Jews was a factor that led to the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290, the first of many such expulsions in Europe.[239][240]

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against Cathar heresy,[241] various institutions, broadly referred to as the Inquisition, were established with the aim of suppressing heresy and securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion and prosecution.[242]

Modern era

Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation

The 15th-century Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. During the Reformation, Martin Luther posted the Ninety-five Theses 1517 against the sale of indulgences.[243] Printed copies soon spread throughout Europe. In 1521 the Edict of Worms condemned and excommunicated Luther and his followers, resulting in the schism of the Western Christendom into several branches.[244]

Other reformers like Zwingli, Oecolampadius, Calvin, Knox, and Arminius further criticized Catholic teaching and worship. These challenges developed into the movement called Protestantism, which repudiated the primacy of the pope, the role of tradition, the seven sacraments, and other doctrines and practices.[243] The Reformation in England began in 1534, when King Henry VIII had himself declared head of the Church of England. Beginning in 1536, the monasteries throughout England, Wales and Ireland were dissolved.[245]

Thomas Müntzer, Andreas Karlstadt and other theologians perceived both the Catholic Church and the confessions of the Magisterial Reformation as corrupted. Their activity brought about the Radical Reformation, which gave birth to various Anabaptist denominations.

Partly in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church engaged in a substantial process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reform.[249] The Council of Trent clarified and reasserted Catholic doctrine. During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states.[250]

Meanwhile, the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 brought about a new wave of missionary activity. Partly from missionary zeal, but under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Throughout Europe, the division caused by the Reformation led to outbreaks of religious violence and the establishment of separate state churches in Europe. Lutheranism spread into the northern, central, and eastern parts of present-day Germany, Livonia, and Scandinavia. Anglicanism was established in England in 1534. Calvinism and its varieties, such as Presbyterianism, were introduced in Scotland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland, and France. Arminianism gained followers in the Netherlands and Frisia. Ultimately, these differences led to the outbreak of conflicts in which religion played a key factor. The Thirty Years' War, the English Civil War, and the French Wars of Religion are prominent examples. These events intensified the Christian debate on persecution and toleration.[251]

In the revival of neoplatonism Renaissance humanists did not reject Christianity; quite the contrary, many of the greatest works of the Renaissance were devoted to it, and the Catholic Church patronized many works of Renaissance art.[252] Much, if not most, of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Church.[252] Some scholars and historians attribute Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution.[253] Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Nicolaus Copernicus,[254] Galileo Galilei,[255] Johannes Kepler,[256] Isaac Newton[257] and Robert Boyle.[258]

Post-Enlightenment

In the era known as the Great Divergence, when in the West, the Age of Enlightenment and the scientific revolution brought about great societal changes, Christianity was confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies, such as versions of socialism and liberalism.[259] Events ranged from mere anti-clericalism to violent outbursts against Christianity, such as the dechristianization of France during the French Revolution,[260] the Spanish Civil War, and certain Marxist movements, especially the Russian Revolution and the persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union under state atheism.[261][262][263][264]

Especially pressing in Europe was the formation of nation states after the Napoleonic era. In all European countries, different Christian denominations found themselves in competition to greater or lesser extents with each other and with the state. Variables were the relative sizes of the denominations and the religious, political, and ideological orientation of the states. Urs Altermatt of the University of Fribourg, looking specifically at Catholicism in Europe, identifies four models for the European nations. In traditionally Catholic-majority countries such as Belgium, Spain, and Austria, to some extent, religious and national communities are more or less identical. Cultural symbiosis and separation are found in Poland, the Republic of Ireland, and Switzerland, all countries with competing denominations. Competition is found in Germany, the Netherlands, and again Switzerland, all countries with minority Catholic populations, which to a greater or lesser extent identified with the nation. Finally, separation between religion (again, specifically Catholicism) and the state is found to a great degree in France and Italy, countries where the state actively opposed itself to the authority of the Catholic Church.[265]

The combined factors of the formation of nation states and ultramontanism, especially in Germany and the Netherlands, but also in England to a much lesser extent,[266] often forced Catholic churches, organizations, and believers to choose between the national demands of the state and the authority of the Church, specifically the papacy. This conflict came to a head in the First Vatican Council, and in Germany would lead directly to the Kulturkampf.[267]

Christian commitment in Europe dropped as modernity and secularism came into their own,[268] particularly in the Czech Republic and Estonia,[269] while religious commitments in America have been generally high in comparison to Europe. Changes in worldwide Christianity over the last century have been significant, since 1900, Christianity has spread rapidly in the Global South and Third World countries.[270] The late 20th century has shown the shift of Christian adherence to the Third World and the Southern Hemisphere in general,[271][272] with the West no longer the chief standard bearer of Christianity. Approximately 7 to 10% of Arabs are Christians,[273] most prevalent in Egypt, Syria and Lebanon.

Demographics

With around 2.4 billion adherents according to a 2020 estimation by Pew Research Center,[1][274][275][276][277][278] split into three main branches of Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern Orthodox, Christianity is the world's largest religion.[3] High birth rates and conversions in the global South were cited as the reasons for the Christian population growth.[279][280] The Christian share of the world's population has stood at around 33% for the last hundred years, which means that one in three persons on Earth are Christians. This masks a major shift in the demographics of Christianity; large increases in the developing world have been accompanied by substantial declines in the developed world, mainly in Western Europe and North America.[281] According to a 2015 Pew Research Center study, within the next four decades, Christianity will remain the largest religion; and by 2050, the Christian population is expected to exceed 3 billion.[282]: 60

.jpg.webp)

According to some scholars, Christianity ranks at first place in net gains through religious conversion.[284][285] As a percentage of Christians, the Catholic Church and Orthodoxy (both Eastern and Oriental) are declining in some parts of the world (though Catholicism is growing in Asia, in Africa, vibrant in Eastern Europe, etc.), while Protestants and other Christians are on the rise in the developing world.[286][287][288] The so-called popular Protestantism[note 7] is one of the fastest growing religious categories in the world.[289][290][291] Nevertheless, Catholicism will also continue to grow to 1.63 billion by 2050, according to Todd Johnson of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity.[292] Africa alone, by 2015, will be home to 230 million African Catholics.[293] And if in 2018, the U.N. projects that Africa's population will reach 4.5 billion by 2100 (not 2 billion as predicted in 2004), Catholicism will indeed grow, as will other religious groups.[294] According to Pew Research Center, Africa is expected to be home to 1.1 billion African Christians by 2050.[282]

In 2010, 87% of the world's Christian population lived in countries where Christians are in the majority, while 13% of the world's Christian population lived in countries where Christians are in the minority.[16] Christianity is the predominant religion in Europe, the Americas, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[16] There are also large Christian communities in other parts of the world, such as Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.[16] In Asia, it is the dominant religion in Armenia, Cyprus, Georgia, East Timor, and the Philippines.[295] However, it is declining in some areas including the northern and western United States,[296] some areas in Oceania (Australia[297] and New Zealand[298]), northern Europe (including Great Britain,[299] Scandinavia and other places), France, Germany, and the Canadian provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec, and some parts of Asia (especially the Middle East, due to the Christian emigration,[300][301][302] and Macau[303]).

The Christian population is not decreasing in Brazil, the southern United States,[304] and the province of Alberta, Canada,[305] but the percentage is decreasing. Since the fall of communism, the proportion of Christians has been stable or even increased in the Central and Eastern European countries.[306] Christianity is growing rapidly in both numbers and percentage in China,[307][3] other Asian countries,[3][308] Sub-Saharan Africa,[3][309] Latin America,[3] Eastern Europe,[306][283] North Africa (Maghreb),[310][309] Gulf Cooperation Council countries,[3] and Oceania.[309]

Despite a decline in adherence in the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion in the region, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian.[16] Christianity remains the largest religion in Western Europe, where 71% of Western Europeans identified themselves as Christian in 2018.[311] A 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that 76% of Europeans, 73% in Oceania and about 86% in the Americas (90% in Latin America and 77% in North America) identified themselves as Christians.[3][16] By 2010 about 157 countries and territories in the world had Christian majorities.[3]

There are many charismatic movements that have become well established over large parts of the world, especially Africa, Latin America, and Asia.[312][313][314][315][316] Since 1900, primarily due to conversion, Protestantism has spread rapidly in Africa, Asia, Oceania, and Latin America.[317] From 1960 to 2000, the global growth of the number of reported Evangelical Protestants grew three times the world's population rate, and twice that of Islam.[318] According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey from the University of Melbourne, since the 1960s there has been a substantial increase in the number of conversions from Islam to Christianity, mostly to the Evangelical and Pentecostal forms.[319] A study conducted by St. Mary's University estimated about 10.2 million Muslim converts to Christianity in 2015;[310][320] according to the study significant numbers of Muslim converts to Christianity can be found in Afghanistan,[310][321] Azerbaijan,[310][321] Central Asia (including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and other countries),[310][321] Indonesia,[310][321] Malaysia,[310][321] the Middle East (including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey,[322] and other countries),[310][321] North Africa (including Algeria, Morocco,[323][324] and Tunisia[325]),[310][321] Sub-Saharan Africa,[310][321] and the Western World (including Albania, Belgium, France, Germany, Kosovo, the Netherlands, Russia, Scandinavia, United Kingdom, the United States, and other western countries).[310][321] It is also reported that Christianity is popular among people of different backgrounds in Africa and Asia; according to a report by the Singapore Management University, more people in Southeast Asia are converting to Christianity, many of them young and having a university degree.[308] According to scholar Juliette Koning and Heidi Dahles of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam there is a "rapid expansion" of Christianity in Singapore, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and South Korea.[308] According to scholar Terence Chong from the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, since the 1980s Christianity is expanding in China, Singapore,[326] Indonesia, Japan,[327][328] Malaysia, Taiwan, South Korea,[16] and Vietnam.[329]

In most countries in the developed world, church attendance among people who continue to identify themselves as Christians has been falling over the last few decades.[330] Some sources view this as part of a drift away from traditional membership institutions,[331] while others link it to signs of a decline in belief in the importance of religion in general.[332] Europe's Christian population, though in decline, still constitutes the largest geographical component of the religion.[333] According to data from the 2012 European Social Survey, around a third of European Christians say they attend services once a month or more.[334] Conversely, according to the World Values Survey, about more than two-thirds of Latin American Christians, and about 90% of African Christians (in Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Zimbabwe) said they attended church regularly.[334] According to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, Christians in Africa and Latin America and the United States have high levels of commitment to their faith.[335]

Christianity, in one form or another, is the sole state religion of the following nations: Argentina (Catholic),[336] Costa Rica (Catholic),[337] the Kingdom of Denmark (Lutheran),[338] England (Anglican),[339] Greece (Greek Orthodox),[340] Iceland (Lutheran),[341] Liechtenstein (Catholic),[342] Malta (Catholic),[343] Monaco (Catholic),[344] Norway (Lutheran),[345] Samoa,[346] Tonga (Methodist), Tuvalu (Reformed), and Vatican City (Catholic).[347]

There are numerous other countries, such as Cyprus, which although do not have an established church, still give official recognition and support to a specific Christian denomination.[348]

| Tradition | Followers | % of the Christian population | % of the world population | Follower dynamics | Dynamics in- and outside Christianity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic Church | 1,329,610,000 | 50.1 | 15.9 | ||

| Protestantism | 900,640,000 | 36.7 | 11.6 | ||

| Eastern Orthodox Church | 220,380,000 | 11.9 | 3.8 | ||

| Other Christianity | 28,430,000 | 1.3 | 0.4 | ||

| Christianity | 2,382,750,000 | 100 | 31.7 |

| Region | Christians | % Christian |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 558,260,000 | 75.2 |

| Latin America–Caribbean | 531,280,000 | 90.0 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 517,340,000 | 62.9 |

| Asia Pacific | 286,950,000 | 7.1 |

| North America | 266,630,000 | 77.4 |

| Middle East–North Africa | 12,710,000 | 3.7 |

| World | 2,173,180,000 | 31.5 |

| Christian median age in region (years) |

Regional median age (years) | |

|---|---|---|

| World | 30 | 29 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 19 | 18 |

| Latin America-Caribbean | 27 | 27 |

| Asia-Pacific | 28 | 29 |

| Middle East-North Africa | 29 | 24 |

| North America | 39 | 37 |

| Europe | 42 | 40 |

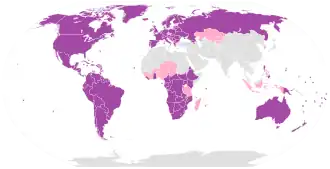

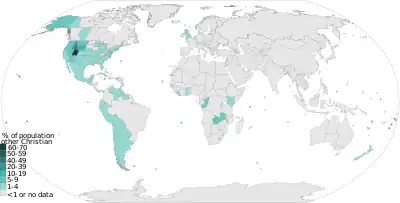

Countries with 50% or more Christians are colored purple; countries with 10% to 50% Christians are colored pink.

Countries with 50% or more Christians are colored purple; countries with 10% to 50% Christians are colored pink. Nations with Christianity as their state religion are in blue.

Nations with Christianity as their state religion are in blue. Distribution of Catholics

Distribution of Catholics.svg.png.webp) Distribution of Protestants

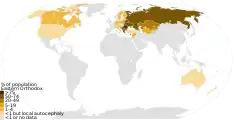

Distribution of Protestants Distribution of Eastern Orthodox

Distribution of Eastern Orthodox Distribution of Oriental Orthodox

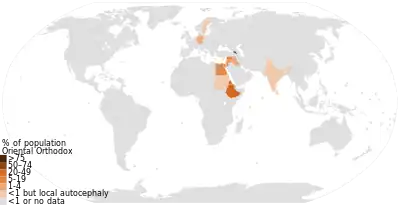

Distribution of Oriental Orthodox Distribution of other Christians

Distribution of other Christians

Churches and denominations

Christianity can be taxonomically divided into six main groups: Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Oriental Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodoxy, the Church of the East, and Restorationism.[14][350] A broader distinction that is sometimes drawn is between Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity, which has its origins in the East–West Schism (Great Schism) of the 11th century. Recently, neither Western nor Eastern World Christianity has also stood out, for example, in African-initiated churches. However, there are other present[351] and historical[352] Christian groups that do not fit neatly into one of these primary categories.

There is a diversity of doctrines and liturgical practices among groups calling themselves Christian. These groups may vary ecclesiologically in their views on a classification of Christian denominations.[353] The Nicene Creed (325), however, is typically accepted as authoritative by most Christians, including the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and major Protestant, such as Lutheran and Anglican denominations.[354]

- (Not shown are non-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and some restorationist denominations.)

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church consists of those particular Churches, headed by bishops, in communion with the pope, the bishop of Rome, as its highest authority in matters of faith, morality, and church governance.[355][356] Like Eastern Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church, through apostolic succession, traces its origins to the Christian community founded by Jesus Christ.[357][358] Catholics maintain that the "one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church" founded by Jesus subsists fully in the Catholic Church, but also acknowledges other Christian churches and communities[359][360] and works towards reconciliation among all Christians.[359] The Catholic faith is detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[361][362]

Of its seven sacraments, the Eucharist is the principal one, celebrated liturgically in the Mass.[363] The church teaches that through consecration by a priest, the sacrificial bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. The Virgin Mary is venerated in the Catholic Church as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven, honoured in dogmas and devotions.[364] Its teaching includes Divine Mercy, sanctification through faith and evangelization of the Gospel as well as Catholic social teaching, which emphasises voluntary support for the sick, the poor, and the afflicted through the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. The Catholic Church operates thousands of Catholic schools, universities, hospitals, and orphanages around the world, and is the largest non-government provider of education and health care in the world.[365] Among its other social services are numerous charitable and humanitarian organizations.

Canon law (Latin: jus canonicum)[366] is the system of laws and legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Catholic Church to regulate its external organisation and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics toward the mission of the church.[367] The canon law of the Latin Church was the first modern Western legal system,[368] and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West.[369][370] while the distinctive traditions of Eastern Catholic canon law govern the 23 Eastern Catholic particular churches sui iuris.

As the world's oldest and largest continuously functioning international institution,[371] it has played a prominent role in the history and development of Western civilization.[372] The 2,834 sees[373] are grouped into 24 particular autonomous Churches (the largest of which being the Latin Church), each with its own distinct traditions regarding the liturgy and the administering of sacraments.[374] With more than 1.1 billion baptized members, the Catholic Church is the largest Christian church and represents 50.1%[16] of all Christians as well as 16.7% of the world's population.[375][376][377] Catholics live all over the world through missions, diaspora, and conversions.

Eastern Orthodox Church

.jpg.webp)

The Eastern Orthodox Church consists of those churches in communion with the patriarchal sees of the East, such as the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.[379] Like the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church also traces its heritage to the foundation of Christianity through apostolic succession and has an episcopal structure, though the autonomy of its component parts is emphasized, and most of them are national churches.

Eastern Orthodox theology is based on holy tradition which incorporates the dogmatic decrees of the seven Ecumenical Councils, the Scriptures, and the teaching of the Church Fathers. The church teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church established by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission,[380] and that its bishops are the successors of Christ's apostles.[381] It maintains that it practises the original Christian faith, as passed down by holy tradition. Its patriarchates, reminiscent of the pentarchy, and other autocephalous and autonomous churches reflect a variety of hierarchical organisation. It recognises seven major sacraments, of which the Eucharist is the principal one, celebrated liturgically in synaxis. The church teaches that through consecration invoked by a priest, the sacrificial bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. The Virgin Mary is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as the God-bearer, honoured in devotions.

Eastern Orthodoxy is the second largest single denomination in Christianity, with an estimated 230 million adherents, although Protestants collectively outnumber them, substantially.[16][13][382] As one of the oldest surviving religious institutions in the world, the Eastern Orthodox Church has played a prominent role in the history and culture of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Near East.[383] The majority of Eastern Orthodox Christians live mainly in Southeast and Eastern Europe, Cyprus, Georgia, and parts of the Caucasus region, Siberia, and the Russian Far East. Over half of Eastern Orthodox Christians follow the Russian Orthodox Church, while the vast majority live within Russia.[384] There are also communities in the former Byzantine regions of Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and in the Middle East. Eastern Orthodox communities are also present in many other parts of the world, particularly North America, Western Europe, and Australia, formed through diaspora, conversions, and missionary activity.

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches (also called "Old Oriental" churches) are those eastern churches that recognize the first three ecumenical councils—Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus—but reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon and instead espouse a Miaphysite christology.

The Oriental Orthodox communion consists of six groups: Syriac Orthodox, Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (India), and Armenian Apostolic churches.[385] These six churches, while being in communion with each other, are completely independent hierarchically.[386] These churches are generally not in communion with the Eastern Orthodox Church, with whom they are in dialogue for erecting a communion.[387] Together, they have about 62 million members worldwide.[388][389][390]

As some of the oldest religious institutions in the world, the Oriental Orthodox Churches have played a prominent role in the history and culture of Armenia, Egypt, Turkey, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan and parts of the Middle East and India.[391][392] An Eastern Christian body of autocephalous churches, its bishops are equal by virtue of episcopal ordination, and its doctrines can be summarized in that the churches recognize the validity of only the first three ecumenical councils.[393]

Some Oriental Orthodox Churches such as the Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, places a heavier emphasis on Old Testament teachings than one might find in other Christian denominations, and its followers adhere to certain practices: following dietary rules that are similar to Jewish Kashrut,[394] require that their male members undergo circumcision,[395] and observes ritual purification.[396][397]

Church of the East

The Church of the East, which was part of the Great Church, shared communion with those in the Roman Empire until the Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorius in 431. Continuing as a dhimmi community under the Sunni Caliphate after the Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, it represented the world's largest Christian denomination in terms of geographical extent. It established dioceses and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea and today's Iraq and Iran, to India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of Kerala), the Mongol kingdoms in Central Asia, and China during the Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries). In the 13th and 14th centuries, the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire, where influential Church of the East clergy sat in the Mongol court.