Hurrian religion

The Hurrian religion was the polytheistic religion of the Hurrians, a Bronze Age people of the Near East who chiefly inhabited the north of the Fertile Crescent. While the oldest evidence goes back to the third millennium BCE, it is best attested in cuneiform sources from the second millennium BCE written not only in the Hurrian language, but also Akkadian, Hittite and Ugaritic. It was shaped by the contacts between Hurrians and various cultures they coexisted with. As a result, the Hurrian pantheon included both natively Hurrian deities and those of foreign origin, adopted from Mesopotamian, Syrian (chiefly Eblaite and Ugaritic), Anatolian and Elamite beliefs. The culture of the Hurrians were not entirely homogeneous, and different local religious traditions are documented in sources from Hurrian kingdoms such as Arrapha, Kizzuwatna and Mitanni, as well as from cities with sizeable Hurrian populations, such as Ugarit and Alalakh.

Hurrian religion was one of the best attested influences of Hittite religion. The Hurrian pantheon is depicted in the rock reliefs from the Hittite sanctuary at Yazılıkaya, which dates to the thirteenth century BCE. Hittite scribes also translated many Hurrian myths into their own language, possibly relying on oral versions passed down by Hurrian singers. Among the best known of these compositions are the cycle of myths describing conflicts between Kumarbi and his son Teššub and the Song of Release. Hurrian influences on Ugaritic and Mesopotamian religion also have been noted, though they are less extensive. Furthermore, it has been argued that the Hurrian myths about a succession struggle between various primordial kings of the gods influenced Hesiod's poem Theogony.

Overview

Hurrians were among the inhabitants of parts of the Ancient Near East,[1] especially the north of the Fertile Crescent.[2] Their presence is attested from Cilicia (Kizzuwatna) in modern Turkey in the west, through the Amik Valley (Mukish), Aleppo (Halab) and the Euphrates valley in Syria, to the modern Kirkuk area (Arrapha) in Iraq in the east.[3] The contemporary term "Hurrian" is derived from words attested in various languages of the Ancient Near East, such as Ḫurri (Hurrian[4]), ḫurvoge (Hurrian), ḫurili (Hittite) and ḫurla (Hittite), which referred respectively to areas inhabited by the Hurrians, the language they spoke, and to the people themselves.[5] It is assumed that these terms were all derived from a Hurrian endonym whose meaning remains unknown.[6] The Mesopotamians often referred to Hurrians as "Subarians",[7] and this name was also applied to them in scholarly literature in the early twentieth century.[8] This term was derived from the geographic name Subartu (Subir),[9] which was a designation for northern areas in Mesopotamian records.[10] The label "Subarian" is now considered obsolete in scholarship.[9]

The term "Hurrian" as used today refers to the cultural[11] and linguistic unity of various groups, and does not designate a single state.[12] The Hurrian language was spoken over a wide area in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, but started to decline in the twelfth century BCE, with only small pockets surviving north of Assyria for some five hundred years after it ceased to be spoken elsewhere.[2] It is now extinct[2] and has no known relatives other than Urartian,[9] known from inscriptions from between the ninth and sixth centuries BCE.[13] It is agreed today that while related, it was not the same language as Hurrian, and separated from it as early as in the third millennium BCE.[14] A distant connection between hypothetical Proto-Hurro-Uratrian and an archaic Northeastern Caucasian language has been proposed based on reconstructions, but it is not widely accepted.[2] The vocabulary of Hurrian is poorly understood,[15] there are also no clear rules about the transcription of Hurrian words and spelling might vary in scholarly literature due to individual authors making different decisions regarding the presence of voiced consonants.[16]

The available evidence of the culture of the Hurrians is similarly fragmentary, and does not offer information about all areas inhabited by them in all time periods.[17] There is also no indication that the religious practice of various Hurrian communities was entirely homogeneous.[18][19] The oldest evidence of Hurrian religious life comes from Urkesh[20] and dates to the third millennium BCE,[21] specifically to the Ur III period.[22] Both of the oldest available sources are royal inscriptions.[23] It is possible that Hurrians were present in the Ancient Near East for much longer, as evidenced by personal names in documents from the Sargonic period and the existence of the Hurrian loanword tibira ("metalworker") in Sumerian.[24]

The Hittite archives of Hattusa are considered to be one of the richest sources of information about Hurrian religion.[25] They consist of both texts written in Hurrian and Hurrian works translated into the Hittite language.[26] Some of them were copies of religious texts from Alalakh, Halab[27] or Kizzuwatna.[28] Several Hurrian ritual texts have also been found during the excavations of Ugarit.[29] There are also references to Hurrian deities in some Akkadian texts from that city.[29] The Amarna letters from king Tushratta of Mitanni and the treaty documents provide evidence about the Hurrian religion as practiced in the Mitanni state.[30] The archives of individual Syrian cities, like Mari, Emar and Alalakh, also contain Hurrian texts.[31] These from the first of these cities date to the reign of Zimri-Lim.[32] The evidence from eastern Hurrian centers is comparatively rare, and pantheons of cities such as Nuzi and Arrapha have to be reconstructed only based on administrative texts.[33] Documents from Nuzi allude to distinct customs such as ancestor worship[34] and maintaining sacred groves.[35] While especially in older scholarship the western and eastern Hurrian pantheons were often treated as separate, Marie-Claude Trémouille notes that the difference should not be exaggerated.[36]

Due to long periods of interchange between Hurrians and other Mesopotamian, Syrian and Anatolian societies it is often impossible to tell which features of Hurrian religion were exclusively Hurrian in origin and which developed through contact with other cultures.[37] As noted by Beate Pongratz-Leisten, transfer of deities likely easily occurred between people who shared a similar lifestyle, such as Hurrians and Mesopotamians, who both were settled urban societies at the time of their first contacts.[38] Religious vocabulary of the Hurrian language was heavily influenced by Akkadian.[39] For example, priests were known as šankunni, a loan from Akkadian šangû.[40] Another term borrowed from this language was entanni, referring to a class of priestesses, derived from entu, itself an Akkadian feminine form of the Sumerian loanword en, "lord."[41]

Gernot Wilhelm highlights that "undue importance has long been attached to the historical significance" of the presence of speakers of an early Indo-European language in the predominantly Hurrian Mitanni empire.[42] Members of its ruling dynasty had names which are linguistically Indo-European[43] and adhered to a number of traditions of such origin, but the historical circumstances of this development are not known.[9] The attested Mitanni deities of Indo-European origin include Indra, Mitra, Varuna and the Nasatya twins,[44] who all only appear in a single treaty between Šattiwaza and the Hittite king Šuppiluliuma I, where they act as tutelary deities of the former.[34] The Hurrianised spellings of their names are Mitra-ššil, Aruna-ššil (or Waruna-ššil), Indra and Našattiyana.[45] It is likely that they were only worshiped by the aristocracy of this kingdom,[45] or just by the ruling dynasty and its circle.[44] At the same time, Mitanni princesses bore theophoric names invoking Ḫepat,[43] king Tushratta referred to Šauška as the "mistress of my land,"[29] and as in the other Hurrian areas, the state pantheon was headed by Teššub.[46] The official correspondence of the Mitanni rulers was written in Akkadian or Hurrian.[47]

Evidence from Urartu in most cases cannot be used in the study of Hurrian religion, as the connection between it and Bronze Age Hurrians is almost exclusively linguistic and does not extend to religious practice or pantheon.[48] For instance, the head of the Urartian pantheon, Ḫaldi, appears to be absent from Hurrian sources.[49]

Deities

Hurrians worshiped many deities of varied backgrounds, some of them natively Hurrian, while others adopted from other pantheons or formed through the process of syncretism.[18][51] Some had "pan-Hurrian" character,[52] while the worship of others was limited to specific locations.[53] A number of deities worshiped by Hurrians in Syria and Kizzuwatna most likely had their origin in a linguistic and religious substrate absorbed first by Eblaites and then, after the fall of Ebla in the third millennium BCE, by Hurrians, who started to arrive in predominantly Amorite Syria in the same time period.[54] Others were Mesopotamian and might have been integrated into the Hurrian pantheon as early as in the third millennium BCE.[55] For example, it has been argued that Nergal was already commonly worshiped by Hurrians in this period.[56] Additionally, logograms of Mesopotamian origin were commonly used to represent the names of Hurrian deities, coexisting in writing with syllabic spellings of their names.[57] Hurrian divine names are often simple and epithet-like, for example Allani means "the lady," Šauška - "the great," and Nabarbi - "she of Nawar."[58] The word referring to gods was eni,[59] plural enna.[34]

Like in other cultures of the Ancient Near East, Hurrian gods were imagined as anthropomorphic.[60] They had to be provided with nourishment, which they received in the form of offerings.[60] The myth of Ḫedammu attests that while in theory gods would be capable of laboring themselves to acquire food, it would jeopardize their position in the universe.[60] Gods were represented in the form of statues, often made of precious metals and stones.[61] Such figures typically held symbols which served as the attributes of the given deity.[61] They had to be clothed[61] and anointed, as evidenced by lists of oil offerings.[62] It was believed that if a deity's representation is not treated properly, it might enrage them and result in various repercussions.[63] Lunar and solar eclipses in particular were viewed as a sign of the displeasure of the corresponding deities.[64]

The head of the Hurrian pantheon was Teššub, who was a weather god.[22] While it is assumed that he was not necessarily regarded as the head of the pantheon from the very beginning,[55] he likely already acquired this role in the late third millennium BCE.[52] Daniel Schwemer instead argues that was imagined as the king of gods from the beginning.[22] All Hurrians also worshiped Šauška, whose primary spheres of influence were love and war.[29] She could be depicted in both male and female form,[65] and a ritual text mentions her "female attributes" and "male attributes" side by side.[66] Further deities commonly described as "pan-Hurrian" include Kumarbi,[52] who was the "father of gods,"[67] the sun god Šimige, the moon god Kušuḫ,[68] the Mesopotamian god Nergal,[53] Nupatik,[53] whose character and relation to other deities are poorly understood[25] and Nabarbi.[52] Ishara, Allani,[69] Ea[57] and Nikkal are also considered major deities in scholarship.[70] Ḫepat, a Syrian deity incorporated into the western Hurrian pantheon,[71] was considered a major goddess in areas which accepted the theology of Halab.[29]

The concept of sukkal, or divine vizier, well known from Mesopotamian theology, was also incorporated into Hurrian religion.[40] The word itself was loaned into Hurrian and was spelled šukkalli.[40] Much like in Mesopotamia, sukkals were the attendants of the major gods.[25] Known examples include Tašmišu and Tenu, sukkals of Teššub,[72] Undurumma, the sukkal of Šauška,[73] Izzummi, the sukkal of Ea (a Hurrian adaptation of Mesopotamian Isimud),[69] Lipparuma, the sukkal of Šimige, Mukišānu, the sukkal of Kumarbi,[74] and Tiyabenti[75] and Takitu, sukkals of Ḫepat.[76] The war god Ḫešui also had a sukkal, Ḫupuštukar,[77] as did the personified sea, whose sukkal was Impaluri.[78] A single text describes a ritual involving multiple sukkals at once, namely Ḫupuštukar, Izzumi, Undurumma, Tenu, Lipparuma and Mukišanu.[73]

It has been proposed that the general structure of the Hurrian pantheon was modeled either on its Mesopotamian or Syrian counterpart, with the former view being favored by Emmanuel Laroche and Wilfred G. Lambert, and the latter by Lluís Feliu[79] and Piotr Taracha.[55] The structure of individual local variant pantheons was not necessarily identical, for example in the east and in Hurrian texts from Ugarit Šauška was the highest ranked goddess, but in western locations that position could belong to Ḫepat instead.[29]

Lists and groupings of deities

Two lists of Hurrian deities following Mesopotamian models are known, one from Ugarit and the other with Emar.[80] The former is trilingual, with a Sumerian, Hurrian and Ugaritic column, while the latter - bilingual,[80] without a column in the local vernacular language.[81] It is assumed that the list from Emar was a variant of the so-called Weidner god list, which was a part of the standard curriculum of scribal schools in Mesopotamia.[82] Since the entries in the Hurrian column in both lists largely correspond to each other, it is assumed that the Ugaritic scribes added a third column to a work compiled elsewhere in Syria at an earlier point in time, represented by the copy from Emar.[83] Due to the size of the Mesopotamian pantheon documented in god lists in multiple cases the same Hurrian deity is presented as the equivalent of more than one Mesopotamian one,[81] for example Šimige corresponds to both Utu and Lugalbanda.[84] In some cases the logic behind such decisions is not certain, for example the deity Ayakun is listed as the Hurrian counterpart of both Alammuš and Ninsun.[81] In some cases, the Mesopotamian names were simply written phonetically in the Hurrian column, instead of providing a Hurrian equivalent.[81] Examples include Irḫan[85] and Kanisurra.[86] It has been called into question whether some of such entries represent deities which were actually worshiped by the Hurrians.[87] Two entries which are agreed to be purely ancient scholarly constructs are Ašte Anive and Ašte Kumurbineve, whose names mean "the wife of Anu" and "the wife of Kumarbi."[88] They are neologisms meant to mimic the names in the column listing Mesopotamian deities.[89] Additionally, the equation between Teššub, the Ugaritic weather god Baal and the goddess Imzuanna is assumed to be an example of scribal word play, rather than theological speculation.[90] The first cuneiform sign in Imzuanna's name, IM, could be used as a logographic representation of the names of weather gods.[90]

In the western Hurrian centers, gods were also arranged in lists known as kaluti.[91] It has been proposed that this term was derived from Akkadian kalû, "all" or "totality,"[92] though the literal translation of the Hurrian term is "circle" or "round of offerings."[91] Examples are known from Hattusa and Ugarit, and in both cases, most likely follow the order established in Halab.[45] Typically, deities were divided by gender in them.[45] The kaluti of Teššub include deities such as Tašmišu, Anu, Kumarbi, Ea, Kušuḫ, Šimige, Hatni-Pišaišapḫi, Aštabi, Nupatik, Šauška, Pinikir, Hešui, Iršappa, Tenu, Šarruma, Ugur (identified as "Ugur of Teššub"), and more.[93] Furthermore, the goddess Ninegal belonged to the circle of Teššub.[71] The Hurrian form of her name is Pentikalli.[94] The kaluti of Ḫepat included her children Šarruma, Allanzu and Kunzišalli, as well as the following deities: Takitu, Hutena and Hutellura, Allani, Ishara, Šalaš, Damkina, (Umbu-)Nikkal, Ayu-Ikalti (the Mesopotamian dawn goddess Aya), Šauška with her servants Ninatta and Kulitta, Nabarbi, Šuwala, Adamma, Kubaba, Hašuntarhi, Uršui-Iškalli and Tiyabenti.[71] Kaluti of other deities are also known, for example Nikkal[95] and Šauška.[96]

A distinctive Hurrian practice, most likely of Syrian origin, was the worship of pairs of deities as if they were a unity.[97] Examples include the pairs Ninatta and Kulitta, Ishara and Allani, Hutena and Hutellura,[97] or Adamma and Kubaba.[98] Another possible dyad was the Kizzuwatnean "Goddess of the Night" and Pinikir,[99] a deity of Elamite origin originally worshiped in Susa[100] who most likely was incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon via a Mesopotamian intermediary, possibly as early as in the third millennium BCE.[55] According to Gary Beckman, based on linguistic evidence it is improbable that she was received directly from Elam.[101] Two manifestations of the same deity could be worshiped as a dyad too, for example two forms of Nupatik or Tiyabenti.[97]

Šarrēna

A special class of figures venerated by the Hurrians were so-called šarrēna.[39] This term is a combination of the Akkadian word šarri and a Hurrian plural suffix.[102] It is possible to translate it simply as "divinized kings."[39] Mary R. Bachvarova describes the šarrēna as "heroes from far away and long ago."[103] Like the names of gods, the names of šarrēna[104] and the term itself were preceded by the dingir sign, so-called "divine determinative," which was used to designate divine names in cuneiform.[103] The word designating the deified kings differed from that used to refer to then-contemporary earthly rulers, ewri.[40]

Examples of šarrēna include well known legendary Mesopotamian rulers (Gilgamesh), historical Mesopotamian kings (Sargon, Naram-Sin) and mythical antagonists from the Hurrian cycle of Kumarbi ("Silver", Ḫedammu; the latter's name was erroneously treated as belonging to Hita of Awan in the past[104]).[105] Some šarrēna mentioned in related ritual texts are not known from any other sources, namely kings Autalumma of Elam, Immašku of Lullue and Kiklip-atal of Tukriš.[106] All three of these geographic terms referred to areas located in Iran or central Asia.[107] However, Kiklip-atal's name is Hurrian.[108] It has been argued that references to these figures might indicate that an independent Hurrian tradition of historiography existed.[109]

Religious centers

The centers of Hurrian religious life were temples, known as purli or purulle.[35] No separate exclusively Hurrian style of temple construction has been identified.[35] Of the few which have been excavated, these in the east, for example in Nuzi, follow the so-called "bent axis" model well documented in Mesopotamia from the third millennium BCE onward, while the western ones in Syria often adhere to a local plan with an axially arranged forecourt, a cella with a niche for a statue, and an antecella.[35] However, exceptions from the latter rule are known, as a temple from Alalakh, the temple of the weather god of Halab and a building from Ugarit often described as a Hurrian temple follow the bent axis model.[110] While typically temples were dedicated to major members of the Hurrian pantheon, such as Teššub, Allani or Ishara, they often also housed multiple minor deities at the same time.[62]

The notion that specific gods could favor, and reside in, specific cities was present in Hurrian religion, and by extension is attested in Hittite rituals dedicated to Hurrian deities.[111] For example, Teššub was associated with Kumme,[22] Šauška with Nineveh,[20] Kušuḫ with Kuzina,[25][112] Nikkal with Ugarit,[25][97] Nabarbi with Taite,[113] and Ishara with Ebla.[114] While Kumarbi's connection with Urkesh is well documented, in the earliest sources the city was seemingly associated with Nergal.[66] It has also been proposed that his name in this case served as a logographic representation of Kumarbi or perhaps Aštabi, but this remains uncertain.[53] A secondary cult center of Kumarbi was Azuhinnu located east of the Tigris.[66]

Kumme, the main cult center of Teššub was also known as Kummum in Akkadian, Kummiya in Hittite,[22] and later as Qumenu in Urartian.[115] The name of the city has a plausible Hurrian etymology: the verbal root kum refers to building activities, and the suffix -me was used to nominalise verbs.[115] A connection with the Akkadian word kummu, "sanctuary," is less likely.[115] It was most likely located near the border between modern Turkey and Iraq, possibly somewhere in the proximity of Zakho,[18] though this remains uncertain and relies on unproven assumptions about the location of other landmarks mentioned in the same texts.[116] Beytüşşebap has been proposed as another possibility.[116] Oldest sources attesting that it was Teššub's cult center include Hurrian incantations from Mari from the eighteenth-century BCE.[115] Similar evidence is also present in documents pertaining to the reign of Zimri-Lim, one of the kings of the same city, who at one point dedicated a vase to the god of Kumme.[117] It retained its position as an internationally renowned cult center as late as during the Neo-Assyrian period.[118] However, no texts dated to the reign of Sennacherib or later mention it, and its final fate remains unknown.[119] A further center of Teššub's cult mentioned in many sources was his temple in Arrapha,[22] which was called the "City of the Gods" in Hurrian sources.[33] He also had multiple temples in the territories of the Mitanni empire, for example in Kaḫat, Waššukkanni, Uḫušmāni and Irride.[120] The first of these cities has been identified with modern Tell Barri.[121] Through syncretism with the weather god of Halab, he also came to be associated with this city, as attested in sources not only from nearby Syrian and Anatolian cities but also from as far east as Nuzi.[46] Two further temples, only known from Middle Assyrian sources but presumed to be Hurrian in character, were located in Isana and Šura.[120]

Šauška's association with Nineveh goes back at least to the Ur III period.[122] Based on archeological data the city already existed in the Sargonic period, but it is a matter of scholarly debate if it was already inhabited by Hurrians at this time.[123][124] The last source confirming that Nineveh was associated with this goddess is a text from the reign of Sargon II.[125][126] Another temple dedicated to her existed in Arrapha.[62] Additionally, a double temple excavated in Nuzi most likely belonged jointly to her and Teššub.[29]

Kuzina, associated with the moon god, was most likely the Hurrian name of Harran.[127] This city was among the locations where the custom of giving temples ceremonial Sumerian names was observed, even though it was not located within the traditional sphere of influence of Mesopotamian states.[128] The oldest known records of the temple of the moon god located there do not provide it with one, but sources from the reign of Shalmaneser III, Ashurbanipal and Nabonidus confirm that it was known as Ehulhul, "house which gives joy."[129] A double temple dedicated to Kušuḫ and Teššub existed in Šuriniwe in the kingdom of Arrapha.[130]

The religious center of the kingdom of Kizzuwatna was the city of Kummanni.[131] Despite the similarity of names, it was not the same city as Kumme.[132] A Kizzuwatnean temple of Ishara was located on a mountain bearing her name.[133] Furthermore, at least two temples dedicated to Nupatik existed in this area.[25]

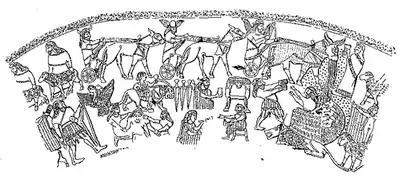

In the Hittite Empire Samuha served as one of the main centers of the worship of Hurrian deities.[134] Another major sanctuary was located in a rocky area near Hattusa, known today as Yazılıkaya (Turkish: "inscribed rock"), though it is uncertain if it can be considered a temple in the strict sense of this term.[135] The walls are decorated with reliefs of two processions of deities.[136] The goddesses follow Ḫepat, while the gods - Teššub, and the order of individual deities overlaps with the known kaluti lists.[136] The central relief depicts these two deities standing face to face.[136]

Practice

At least some deities received daily offerings of bread or flour, as attested in Hattusa and Nuzi.[62] One well known type of Hurrian offerings was keldi, translated as "peace offering"[137] or "goodwill offering."[138] It is also assumed that many monthly or seasonal festivals were observed by Hurrians, but very few of them are well documented, one exception being the hišuwa festival from Kizzuwatna, possibly originally celebrated in Syria.[62] It was meant to guarantee good fortune for the royal couple.[139] Deities who received offering during it included "Teššub Manuzi," Lelluri, Allani, Ishara, two manifestations of Nupatik (pibithi - "of Pibid(a)" and zalmathi - "of Zalman(a)/Zalmat") and the Anatolian goddess Maliya.[139] Another Kizzuwatnean festival, which was dedicated to Ishara, took place in autumn.[140]

A Hurrian ritual calendar is attested in documents from Nuzi.[141] In the earliest sources from the third millennium BCE, when the city was known as Gasur, the local calendar was similar to these from Ebla, Mari, Abu Salabikh and Eshnunna, and the month names used at the time originate in Semitic languages.[142] However, after Hurrians settled in the city, they started to use one of their own, which in some cases could be combined with the old calendar, as evidenced by a document combining month names from both into a sequence.[141] The Hurrian month names in Nuzi were Impurtanni, Arkuzzi, Kurilli, Šeḫali ša dIM (the logogram stands for the name of the god Teššub, while šeḫali might mean "festival"), Šeḫali ša Nergal, Attanašwe, Šeḫlu (followed by a month whose name is not preserved), Ḫuru, Mitirunni (mitirunnu was a festival involving a parade of divine statues) and Ḫutalši.[143] Only the names of a few of the etymologically non-Hurrian months are preserved: Ḫiaru (second; the name refers to a festival also known from northern and western Mesopotamia), Ḫinzuru (third), Tamūzu (fourth), Ulūlu (sixth), Sabūtu (seventh, as indicated by the name), Kinūnu (ninth; the name refers to a festival focused on a ritual brazier), Ḫegalla, Qarrāti and Ḫamannu (position in the calendar unknown).[144] Some Hurrian month names, including a possible cognate of Attanašwe, Atanatim, are also known from Alalakh.[145]

It is possible that Attanašwe, "month of the fathers," was connected to the cult of deceased ancestors, which is well documented in Nuzi.[34] Families apparently owned figurines representing their spirits.[34] In the west, references to "gods of the fathers," enna attanewena, can be found,[146] but it is not clear if they refer to similar customs,[34] and it is possible this term instead referred to nebulously defined ancestors of deities.[147] Funerary rites and other burial practices are poorly represented in known sources.[148] It possible that the term karašk-, known from one of Tushratta's letters to the Egyptian pharaoh referred to a type of mausoleum meant to honor a deceased relative.[148] A single text from Ugarit alludes to the dead being led to their destination by Nupatik, seemingly acting as a psychopomp in this case.[149]

Ritual texts are commonly accompanied by instructions pertaining to music which was supposed to be performed during celebrations, both choral and instrumental.[150] While some contain what is most likely the oldest instance of written musical notation, its decipherment is difficult.[151] One well known example of such a Hurrian hymn comes from Ugarit and is dedicated to Nikkal.[152] A genre of Hurrian songs whose name, zinzabuššiya, is derived from that of an unidentified bird, was associated with the worship of Šauška according to Hittite documents.[96]

Divination is well attested as an element of Hurrian religious practice.[153] Its most commonly employed method combined an inquiry aimed at a specific deity with extispicy, the examination of an animal's entrails.[64] Hepatoscopy, or examination of the liver, is mentioned particularly often.[154] A similar practice is known from Mesopotamia, where the examination of a sheep's liver was commonly understood as a way to gain answers to questions directed as the gods Shamash and Adad.[64] A method of divination involving a specific type of bird, the mušen hurri (Akkadian: "the cave bird" or perhaps "the Hurrian bird," possibly a shelduck or rock partridge) is also known, but it remains uncertain what this procedure entailed.[154]

Hurrian incantations are also well known, though they are often difficult to interpret, and many known examples are unprovenanced.[155] They were imported into Mari and Babylonia as early as in the Old Babylonian period.[155] A well-preserved corpus of such texts is also known from Hattusa.[155] Kizzuwatna was most likely the source of many incantations and other similar formulas.[155] Two examples are the itkalzi ("mouth-washing"[156]) and itkahi series of purification rituals.[155] It has been argued that the former most likely reflect a Mitanni tradition.[157]

Theophoric names

The use of theophoric names by the Hurrians is well documented, and they are considered a valuable source of information about their religious life.[158] At the same time, the earliest Hurrian names, known from records from the Sargonic period, from the time of Naram-Sin's northern campaigns onward,[159] are predominantly non-theophoric.[160] In later periods Teššub was the god most commonly invoked in them.[161] Šimige and Kušuḫ also occur in names from both western and eastern Hurrian cities.[162] Names invoking Kumarbi are uncommon.[66] Allani names are well attested in the Tur Abdin area located in the southeast of modern Turkey.[163] Tilla is very common in theophoric names from Nuzi, where his popularity was comparable to Teššub's.[164] In addition to names of gods, Hurrian theophoric names could also invoke apellatives related to them, natural features (such as the Tigris, known to Hurrians as Aranzaḫ, or the Khabur river) and settlements (Ebla, Nineveh, Arrapha, Nawar, Halab) treated as numina, and occasionally the names of months.[165] Generally, the names of goddesses were invoked in feminine personal names and gods in masculine ones, but Šauška is an exception from this rule.[166]

Examples of Hurrian theophoric names include Ḫutip-Ukur ("Ugur elevated"), Kirip-Tilla ("Tilla set free"), Unap-Teššup ("Teššub came"),[167] Kušuḫ-ewri ("Kušuḫ is a lord"), Nikkal-mati ("Nikkal is wisdom"),[168] Arip-Allani ("Allani gave [a child]"),[169] Arip-Kumarwe ("Kumarbi gave [a child]") and Ḫazip-Ishara ("Ishara heard").[170] Names combining Hurrian elements with Sumerian, Akkadian or Anatolian ones are uncommon, but some examples are known, among them Lu-Šauša and Ur-Šauša from Girsu in Mesopotamia (both meaning "man of Šauša," a variant form of Šauška), Eḫli-Addu ("save, Addu!") from Alalakh, Šauška-muwa ("the one who has the courage of Šauška") from Amurru, and Gimil(li)-Teššub (possibly "favor of Teššub," but the first element might also be an unknown Hurrian word) and Teššub-nīrārī ("Teššub is my helper") from Nuzi.[159]

Cosmology

The myth Song of Ullikummi is one of the few Hurrian texts offering a view of this culture's cosmology.[171] It mentions that the separation of heaven and earth occurred in the distant past, at the beginning of time.[172] The tool used to accomplish this was a copper sickle,[173] referred to as the "former sickle."[174] It was believed that they were subsequently placed on the back of the giant Upelluri, who was already alive during their separation.[175] Volkert Haas assumed that Upelluri stood in the sea,[176] but according to Harry Hoffner he lived underground.[177]

The Hurrian term referring to the concept of a divine Earth and Heaven was eše hawurni.[34] According to Piotr Taracha, the Earth-Heaven pair should be considered "pan-Hurrian," similar to Teššub, Šauška, Kumarbi, Šimige and Kušuḫ, and as such can be found in religious texts from all areas inhabited by Hurrians, from Kizzuwatna in modern Turkey to the Zagros Mountains.[71] However, they were not regarded as personified deities.[34] In offering lists, they typically appear at the very end, alongside mountains, rivers, springs, the sea (Kiaše), winds and clouds.[178] They are also present in incantations.[155] It has been argued that figures number 28 and 29 from the Yazılıkaya reliefs, a pair of bull-men, are holding a symbol of Heaven and standing on a symbol of Earth.[65]

Hurrians also believed in the underworld, which they referred to as the "Dark Earth" (timri eže).[179] It was ruled by the goddess Allani, whose name means "queen" or "lady" in Hurrian.[179] She resided in a palace located at the gates of the land of the dead.[180] The determination of each person's fate by Hutena and Hutellura took place in the underworld as well.[181] The underworld was also inhabited by a special class of deities,[182] Ammatina Enna (Hittite: Karuileš Šiuneš, logographically: dA.NUN.NA.KE[183]), whose name can be translated as "Former Gods" or "Primordial Gods."[146] Usually, a dozen of them are listed at a time, though one of the treaties of the Hittite king Muwatalli II only mentions nine, and in ritual texts they may at times appear in smaller or, rarely, bigger groups, with one listing fifteen of them.[94] The standard twelve members of the group were Nara, Napšara, Minki, Tuḫuši, Ammunki, Ammizzadu, Alalu, Anu, Antu, Apantu, Enlil and Ninlil.[179] The origin of those deities was not homogeneous: some were Mesopotamian in origin (for example Anu, Enlil and their spouses), while others have names which do not show an affinity with any known language.[179] The primordial gods appear to be absent from known Mittani documents.[184] They were regarded as ritually impure, and as such could be invoked in purification rituals to help with banishing the earthly causes of impurity to the underworld.[182] Birds were traditionally regarded as an appropriate offering for them.[185]

In rituals, the underworld could be reached with the use of āpi (offering pits),[182] which had to be dug as part of preparation of a given ritual.[186] They could be used either to send the sources of impurity to the underworld, or to contact its divine inhabitants.[186] The name of one of the eastern Hurrian settlements, Apenašwe, was derived from the same word and likely means "place of the pits."[182]

Mythology

Hurrian myths are known mostly from Hittite translations and from poorly preserved fragments in their native language.[67] Colophons often refer to these compositions using the Sumerian logogram SÌR, "song."[187] It is possible that the myths were transferred to Hittite cities orally by Hurrian singers, who dictated them to scribes.[188]

Cycle of Kumarbi

The Kumarbi Cycle has been described as "unquestionably the best-known belletristic work discovered in the Hittite archives."[189] As noted by Gary Beckman, while the myths about Kumarbi are chiefly known from Hittite translations, their themes, such as conflict over kingship in heaven, reflect Hurrian, rather than Hittite, theology.[190] They are conventionally referred to as "cycle," but Alfonso Archi points out that this term might be inadequate, as evidently a large number of myths about the struggle between Teššub and Kumarbi existed, and while interconnected, they could all function on their own as well.[191] Anna Maria Polvani proposes that more than one "cycle" of myths focused on Kumarbi existed.[192] The myths usually understood as forming the Kumarbi Cycle are the Song of Kumarbi, Song of LAMMA, Song of Silver, Song of Ḫedammu and Song of Ullikummi.[193][194][191] Examples from outside this conventional grouping include Song of Ea and the Beast, a myth dealing with the primordial deity Eltara, and myths about struggle with the personified sea.[191]

Beings inhabiting the sea and the underworld are generally described as allied with Kumarbi and aid him in schemes meant to dethrone Teššub.[195] His allies include his father, the primordial god Alalu, the sea god Kiaše, his daughter Šertapšuruḫi, the sea monster Ḫedammu, and the stone giant Ullikummi.[177] The term tarpanalli, "substitute," is applied to many of the adversaries who challenge Teššub's rule directly on Kumarbi's behalf.[174] In most compositions, Kumarbi's plans are successfulat first, but in the end Teššub and his allies overcome each new adversary.[72] Among the weather god's allies are his siblings Šauška and Tašmišu, his wife Ḫepat, the sun god Šimige, the moon god Kušuḫ and Aštabi.[177] It has been pointed out that the factions seem to reflect the opposition between heaven and the underworld.[177]

Song of Kumarbi

The Song of Kumarbi begins with the narrator inviting various deities to listen to the tale, among them Enlil and Ninlil.[196] Subsequently the reigns of the three oldest "Kings in Heaven" are described: Alalu, Anu and finally Kumarbi.[196] Their origin is not explained,[196] but there is direct evidence in other texts that Alalu was regarded Kumarbi's father.[197][198] Alalu is dethroned by Anu, originally his cupbearer, after nine years, and flees to the underworld.[199] After nine years, Anu meets the same fate at the hands of his own cupbearer, Kumarbi.[199] He tries to flee to heaven, but Kumarbi manages to attack him and bites off his genitals.[199] As a result, he becomes pregnant with three gods: the weather god Teššub, his brother Tašmišu,[200] and the river Tigris, known to the Hurrians as Aranzaḫ (written with the determinative ID, "river," rather than with a dingir, the sign preceding names of deities).[201] Kumarbi apparently spits out the baby Tašmišu, but he cannot get rid of the other two divine children.[200] In the next scene, Teššub apparently discusses the optimal way to leave Kumarbi's body with Kumarbi himself, Anu and Ea, and suggests that the skull needs to be split to let him get out.[202] The procedure is apparently performed by the god Ea, and subsequently the fate goddesses arrive to repair Kumarbi's skull.[202] The birth of Aranzaḫ is not described in detail.[203] Kumarbi apparently wants to instantly destroy Teššub, but he is tricked into eating a basalt stone instead and the weather god survives.[204] The rest of the narrative is poorly preserved, but Teššub does not yet become the king of the gods[205] even though he apparently dethroned Kumarbi.[206] He curses Ea because of this, but one of his bulls rebukes him for it[205] because of the potential negative consequences,[206] though it is not clear whether he considers him a particularly dangerous ally of Kumarbi or a neutral party who should not be antagonized.[207]

Song of LAMMA

The beginning of the Song of LAMMA is lost, but the first preserved fragment describes a battle in which the participants are Teššub and his sister Šauška on one side and the eponymous god on the other.[208] The identity of the god designed by the logogram dLAMMA is uncertain, though Volkert Haas and Alfonso Archi assume that he might be Karḫuḫi, a god from Carchemish, due to his association with Kubaba mentioned in this myth.[209] The Song of Kumarbi does not mention the birth of Šauška, even though she is referred to as the sister of both Teššub and Tašmišu in other texts.[126] It is possible some clues about this situation were present in sections which are not preserved.[126] After defeating Teššub and his sister, LAMMA is most likely appointed to the position of the king of the gods by Ea.[208] Kubaba urges him to meet with the Former God and other high-ranking deities and bow down to them, but LAMMA ignores her advice, arguing that since he is now the king, he should not concern himself with such matters.[210] The wind brings his words to Ea, who meets with Kumarbi, and tells him they need to dethrone LAMMA because his actions resulted in people no longer making offerings to the gods.[211] He informs LAMMA that since he does not fulfill his duty and never summons the god for an assembly, his reign needs to end, and additionally tells one of the Former Gods, Nara, to gather various animals for an unknown purpose.[208] The rest of the narrative is poorly preserved,[208] but in the end, LAMMA is defeated, and acknowledges the rule of Teššub.[212]

Song of Silver

The Song of Silver focuses on a son of Kumarbi and a mortal woman, the eponymous Silver, whose name is not written with the divine determinative.[174] Due to growing up without a father, he is derided by his peers.[213] His mother eventually tells him that his father is Kumarbi, and that he can find him in Urkesh.[214] However, when he arrives there, it turns out that Kumarbi has temporarily left his dwelling.[214] It is uncertain what happens next, but most likely Silver temporarily became the king of the gods[214] and subsequently he "dragged the Sun and the Moon down from heaven."[174] Teššub and Tašmišu apparently discuss his violent acts, but the former doubts that they can defeat him because apparently even Kumarbi was unable to do it.[215] The ending of the narrative is not preserved,[216] but it is assumed that in every myth, the opponent of Teššub was eventually defeated.[217]

Song of Ḫedammu

The Song of Ḫedammu begins with the betrothal of Kumarbi and Šertapšuruḫi, the daughter of his ally, the sea god Kiaše.[217] They subsequently have a son together, the sea monster Ḫedammu.[218] He is described as destructive and voracious.[217] Šauška is the first to discover his rampage and informs Teššub about it.[217] Apparently a confrontation between gods occurs, but Ea breaks it up and reminds both sides of the conflict - the allies of Teššub and of Kumarbi - that the destruction caused by their battles negatively impacts their worshipers, and that they risk having to labor themselves to survive.[217] Kumarbi is apparently displeased about being admonished,[219] which according to Harry Hoffner might be the reason why in the Song of Ullikummi they are no longer allies.[217] Šauška subsequently forms a plan to defeat Ḫedammu on her own and enlists the help of her handmaidens Ninatta and Kulitta.[217] She seduces the monster with the help of a love potion, and apparently manages to bring him to the dry land.[220] The ending of the narrative is not preserved, but it is agreed that in the end Ḫedammu was defeated, like the other antagonists.[217]

Song of Ullikummi

In the Song of Ullikummi, Kumarbi creates a new adversary for Teššub yet again.[220] The monster is a diorite giant bearing the name Ullikummi, meant to signal his purpose as the destroyer of Teššub's city, Kumme.[221] To shield him from the eyes of Teššub's allies, Kumarbi tells his allies, the Irširra (perhaps to be identified as goddesses of nursing and midwifery[222]) to hide him in the underworld, where he can grow in hiding on the shoulders of Upelluri.[223] He eventually grows to such an enormous size that his head reaches the sky.[223] The first god to notice him is Šimige, who instantly tells Teššub.[223] The weather god and his siblings then go to Mount Hazzi to observe the monster.[223] Šauška attempts to defeat the new adversary the same way as Ḫedammu, but fails, because Ullikummi is deaf and blind.[223] While the myths regarded as belonging to the Kumarbi Cycle today were necessarily arranged into a coherent whole, based on this fragment it is agreed that the compilers of the Song of Ullikummi were familiar with the Song of Ḫedammu.[174] A sea wave informs Šauška about the futility of her actions and urges her to tell Teššub he needs to battle Ullikummi as soon as possible.[223]

The initial confrontation between Teššub and Ullikummi apparently fails, and the gathered gods urge Aštabi to try to confront him.[224] However, he is also unsuccessful, and falls into the sea alongside his seventy followers.[224] Ullikummi continues to grow, and finally blocks the entrance to the temple of Ḫepat in Kumme.[225] Ḫepat, worried about the fate of her husband, tasks her servant Takitu with finding out what happened to him.[225] Takitu quickly returns, but her words are not preserved.[226] After a missing passage most likely dealing with Teššub's fate, Tašmišu arrives in Kumme and informs Ḫepat that her husband will be gone for a prolonged time.[225] Afterwards he meets with Teššub and suggests that they need to meet with Ea.[227] They travel to "Apzuwa" (Apsu[228]), present their case to Ea, and beg him for help.[229] Ea subsequently meets with Enlil to inform him about the monstrous size of Ullikummi and the danger he poses to the world.[230] Later he seeks Upelluri out in order to find out how to defeat Ullikummi, and asks him if he is aware of the identity of the monster growing on his back.[175] As it turns out, Upelluri did not notice the new burden at first, but eventually he starts to feel discomfort, something that according to this text he did not experience even during the separation of heaven and earth.[175] After talking to him, Ea tells the Former Gods to bring him the tool which was used to separate heaven and earth.[231][175] A second confrontation occurs, and Ullikummi apparently taunts Teššub, telling him to "behave like a man" because Ea is now on his side.[232] The rest of the final tablet is broken off,[175] but it is assumed the ancient tool was used to defeat Ullikummi.[174]

Other related myths

In the Song of Ea and the Beast, the eponymous god learns about the destiny of Teššub from a mysterious animal.[233] The myth of Eltara describes a period of rule of the eponymous god, and additionally alludes to a conflict involving the mountains.[234] Eltara is described in similar terms as Alalu and Anu in the Song of Kumarbi.[235] It is assumed that his name is a combination of the name of the Ugaritic god El and the suffix -tara.[197]

Myths about the sea

Song of the Sea might have been another myth belonging to the Kumarbi cycle, though this remains uncertain.[236] A number of possible fragments are known, but the plot remains a mystery, though it has been established that both the sea and Kumarbi are involved.[237] Ian Rutherford speculates that this myth was either an account of a battle between Teššub and the sea, or, less likely, a flood myth or a tale about the origin of the sea.[236]

A further fragmentary Hurrian text which might be a part of the Song of the Sea[238] describes an event during which the sea demanded a tribute from the gods, while Kumarbi possibly urged the other deities to fulfill his demands.[239] Šauška was apparently tasked with bringing the tribute.[240][241]

Another myth which alludes to conflicts with sea[242] focuses on Šauška and the mountain god Pišaišapḫi, portrayed as a rapist.[243] To avoid punishment, he pleads that he can tell her about Teššub's battle with the sea and the rebellion of the mountain gods against him which followed it in return for overlooking his crime.[242]

Song of Release

The Song of Release is considered a well-studied myth.[244] It revolves around Teššub's efforts to free the inhabitants of the city Igingalliš from slavery, imposed upon them by Ebla.[244] Since it is only preserved in fragments, and most of them have no colophons, the exact order of events in the plot is uncertain.[245] The cast includes the weather god Teššub, the goddess of the netherworld Allani, Ishara, the tutelary goddess of Ebla, as well a number of human characters: the Eblaite king Megi (whose name is derived from mekum, the royal title used in Ebla[246]), Zazalla, the speaker of the Eblaite assembly, Purra, the representative of the subjugated citizens of Igingalliš, and Pizigarra, a man from Nineveh whose role in the story remains unknown, even though he is introduced in the proem.[247]

Teššub apparently first contacts Megi and promises him that his city will receive his blessing if he agrees to release the slaves but will be destroyed if he does not.[248] The king relays this message to the senate, but the speaker, Zazalla, refuses to fulfill the request,[248] and apparently derisively asks if Teššub is himself poor if he makes such demands.[249] Megi, who is sympathetic to the request, has to tell Teššub that even though he would like to return the men of Igingalliš their freedom, the assembly of his city makes this impossible.[248] In another passage, Ishara most likely tries to avert the destruction of her city by negotiating with Teššub, though the details of her role are uncertain.[250]

A scene whose meaning and connection to the rest of the plot continue to be disputed in scholarship is the meeting between Allani and Teššub held in the underworld.[251] She prepares a banquet for him, and makes him sit next to the Former Gods, typically portrayed as his opponents.[251] This might have represented a reconciliation between the underworld and heaven, thought it has also been proposed that the scene was meant to mirror the beliefs about the entrance into the afterlife, with the Former Gods taking the role of deceased ancestors, or that Teššub was imprisoned in the underworld in a similar manner as Inanna in the well-known myth about her descent into the underworld.[252]

Other myths

Song of Hašarri ("Oil"[253]) focuses on Šauška and the eponymous being,[254] a personified[255] olive tree[254] who she protects from danger.[256]

A short myth describes how Takitu was sent by her mistress Ḫepat on a journey to Šimurrum.[257]

The tale of Kešši focuses on a human hero.[258] After marrying a woman named Šintalimeni he apparently forgets about paying proper reverence to the gods.[258] The narrative is poorly preserved, but it is known that it involves the hero's mother interpreting his dreams, as well as a hunt in the mountains, which was most likely the central plotline.[258]

A further genre of Hurrian works were fables which often involved gods but were primarily focused on presenting a moral.[259] These include the tales of Appu and Gurparanzaḫ.[260] The latter is poorly preserved, but focuses on the eponymous human hero,[261] apparently portrayed as an archer and hunter.[258] It takes place in Agade, which the Hurrians seemingly regarded as a legendary model of ideal governance.[258] The personification of the Tigris, Aranzaḫ, appears in this narrative in an active role as the hero's ally.[258] In one of the surviving fragments, he apparently meets with the fate goddesses.[261]

Hurrian scribes sometimes directly adapted Mesopotamian myths, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and Atrahasis.[262] They could be reworked to better suit the sensibilities of Hurrian audiences.[262] For example, Šauška replaces Ishtar in the Hurrian translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh.[263] A scene exclusive to the adaptation involves Gilgamesh meeting the personified sea, seemingly accompanied by his Hurrian sukkal Impaluri.[264] In the surviving passage the hero greets the marine deity and is cursed in response.[264] A reworking of Atrahasis in which Kumarbi replaces Enlil is only known from a single small fragment.[265]

Influence on other religions of the Ancient Near East

Hittite religion

Hurrian religion influenced Hittite religion, especially in the imperial period of the Hittite state's history.[266] The year 1400 BCE is sometimes used to mark the beginning of the period of particularly extensive Hurrian influence.[267] There is no indication that Hurrian was widely spoken in the original Hittite territories, but it gained a degree of prominence in the royal court and in scribal circles, as reflected in the Hittite corpus of cuneiform texts.[157] Hurrian deities enter the dynastic pantheon of the Hittite kings as well.[268] They could be identified with Hittite ones, for example Šimige was considered analogous to the Sun god of Heaven[269] and Teššub - to the Anatolian weather god Tarḫunna.[270] However, such equations were not necessarily widely recognized, for example Piotr Taracha doubts that the notion that the Sun goddess of Arinna was the same as Hurrian Ḫepat, known from a prayer of queen Puduḫepa, was a part of the beliefs of the general populace of the empire.[271] The official pantheon, the "Thousand Gods of Hatti," included Hurrian and Anatolian deities, but also Syrian and Mesopotamian ones.[178]

Many Hurrian myths are known from their Hittite translations, including the cycle of Kumarbi.[271] Copies in Hurrian and bilinguals are also known, though they are less common.[272] Most likely Hittite scribes worked with either oral or written originals of northern Mesopotamian, Syrian and southern Anatolian (Kizzuwatnean) origin.[273] While they retained the label of "songs," it cannot be established if they were necessarily performed in a religious context.[272] It has been pointed out that the Hittite interest in myths about Teššub was likely rooted in the structure of their native pantheon, also headed by a weather god, and on his role in royal ideology.[274]

Ugaritic religion

Hurrian religion is considered to be a major influence on Ugaritic religion, whose core component was most likely Amorite.[275] In addition to at least twenty one Hurrian texts and five Hurro-Ugaritic bilingual ones,[276] instances of Hurrian religious terminology appearing in purely Ugaritic sources are known.[275] Denis Perdee notes that the impact of Hurrians had on the religious life of this city makes it possible to differentiate the system of beliefs of its inhabitants from these known from coastal areas further south, conventionally referred to as Canaanite religion.[275] Ugaritic and Hurrian languages coexisted, and it was possible for members of the same family to have names originating in either of them.[277] The Hurrian deities attested in theophoric names known from documents this city include Teššub (seventy names, seven belonging to people from outside Ugarit),[278] Šarruma (twenty eight names, three from outside the city) Šimige (nine names), Kušuḫ (six names, one belonged to a person from outside Ugarit),[279] Iršappa (three names),[278] Kubaba, Nupatik, Ishara and possibly Šauška (one name each).[280] It is possible that the same priests were responsible for performing rituals involving Ugaritic and Hurrian deities.[281] Aaron Tugendhaft goes as far as suggesting it might be impossible to divide the gods worshiped in this city into separate Ugaritic and Hurrian pantheons.[87] At the same time, the extent of Hurrian influence on the other spheres of the history of Ugarit is disputed.[282]

Mesopotamian religion

Tonia Sharlach argues that Mesopotamian documents show that kings from the Third Dynasty of Ur "respected Hurrians' religious or ritual expertise," as evidenced by the appointment of a Hurrian named Taḫiš-atal to the position of a court diviner during the reign of Amar-Sin.[283] Other sources also indicate that Hurrians were perceived as experts in magic in Mesopotamia, and many Hurrian incantations are present in Old Babylonian collections of such texts from both southern Mesopotamian cities and Mari.[153] Most of them are either related to potency or meant to prevent or counter the effects of an animal's bite.[153]

Some Hurrian deities were incorporated into the Mesopotamian pantheon. For example, documents from the Ur III period show that Allani,[163] Šauška[284] and Šuwala were incorporated into Mesopotamian religion in this period.[285] Ninatta and Kulitta are attested in Neo-Assyrian sources in relation to Ishtar of Assur[66] and Ishtar of Arbela.[286] Similarly, Šeriš and Hurriš, the bulls who pulled Teššub's chariot, are attested in association with the Mesopotamian weather god Adad.[120] Nabarbi, Kumarbi and Samnuha appear in a tākultu ritual.[66] It is also assumed that Umbidaki, worshiped in the temple of Ishtar of Arbela, was analogous to Nupatik, possibly introduced to this city after a statue of him was seized in a war.[286] Furthermore, the name of Šala, the wife of Adad, is assumed to be derived from the Hurrian word šāla, daughter.[287]

Other proposals

The fragmentary text about Šauška bringing tribute to the sea god has been compared to an Egyptian myth about the goddess Astarte, recorded in the so-called "Astarte papyrus."[288] However, Noga Ayali-Darshan considers a direct connection between them implausible as in the latter composition the sea god is named Ym rather than Kiaše.[289] She proposes that Egyptians relied on a text written in a Western Semitic language, not necessarily identical with the Ugaritic Baal Cycle, which also describes a similar conflict.[289]

It has been suggested that the succession of primordial rulers of the gods described in the Song of Kumarbi was an influence on Hesiod's Theogony,[189] though according to Gary Beckman it is not impossible that both texts simply used similar topoi which belonged to what he deems a Mediterranean koine, a shared repertoire of cultural concepts.[189] However, he accepts that the birth of Teššub in the same myth was a template for the well known Greek myth about the birth of Athena from the skull of Zeus.[203]

References

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 1.

- Wilhelm 2004, p. 95.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 42.

- Wilhelm 2004, p. 105.

- Wilhelm 2004, pp. 95–96.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 1–2.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 8.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 2.

- Wilhelm 2004, p. 96.

- Pongratz-Leisten 2012, p. 96.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 12.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 6.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 3–4.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 4.

- Wilhelm 2004, p. 117.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. VI.

- Archi 2013, pp. 1–2.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 49.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 114.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 11.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 116.

- Schwemer 2008, p. 3.

- Trémouille 2000, pp. 116–117.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 8–9.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 53.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 57–59.

- Archi 2013, pp. 2–3.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 118.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 51.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 18–19.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 2–3.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 117.

- Haas 2015, p. 544.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 57.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 66.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 121.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 122.

- Pongratz-Leisten 2012, p. 85.

- Archi 2013, p. 5.

- Archi 2013, p. 6.

- Hoffner 2010, p. 217.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 5.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 130.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 18.

- Archi 2013, p. 9.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 50.

- Archi 2013, p. 2.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 41.

- Schwemer 2001, p. 445.

- Taracha 2009, pp. 94–95.

- Archi 2002, p. 31.

- Archi 2013, p. 7.

- Archi 2013, p. 8.

- Archi 1997, pp. 417–418.

- Taracha 2009, p. 120.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 9.

- Archi 1993, p. 28.

- Archi 2013, pp. 6–7.

- Pardee 2002, p. 24.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 63.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 67.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 64.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 67–68.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 68.

- Taracha 2009, p. 95.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 52.

- Archi 2013, p. 1.

- Archi 2013, pp. 7–8.

- Archi 2013, p. 10.

- Archi 2013, p. 11.

- Taracha 2009, p. 119.

- Schwemer 2008, p. 6.

- Kammenhuber 1972, p. 370.

- Archi 2013, p. 12.

- Beckman 1999, p. 37.

- Wilhelm 2013, p. 417.

- Kammenhuber 1972, p. 369.

- Haas 2015, p. 409.

- Feliu 2003, p. 300.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 78.

- Simons 2017, p. 83.

- Simons 2017, p. 82.

- Tugendhaft 2016, pp. 172–173.

- Simons 2017, p. 86.

- Simons 2017, p. 84.

- Tugendhaft 2016, p. 175.

- Tugendhaft 2016, p. 177.

- Tugendhaft 2016, pp. 177–178.

- Tugendhaft 2016, p. 181.

- Tugendhaft 2016, p. 179.

- Taracha 2009, p. 118.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 127.

- Taracha 2009, pp. 118–119.

- Archi 1990, p. 116.

- Archi 2013, p. 21.

- Beckman 1998, p. 6.

- Taracha 2009, p. 128.

- Archi 2013, p. 15.

- Miller 2008, p. 68.

- Miller 2008, pp. 68–69.

- Beckman 1999, p. 28.

- Bachvarova 2013, p. 38.

- Bachvarova 2013, p. 24.

- Wilhelm 2003, p. 393.

- Bachvarova 2013a, p. 41.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 10.

- Fuchs 2005, p. 174.

- Wilhelm 1982, p. 13.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 73.

- Válek 2021, pp. 53–54.

- Pongratz-Leisten 2012, p. 92.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 126.

- Taracha 2009, p. 121.

- Archi 2002, p. 27.

- Radner 2012, p. 254.

- Radner 2012, p. 255.

- Radner 2012, p. 256.

- Radner 2012, pp. 255–256.

- Radner 2012, p. 257.

- Schwemer 2008, p. 4.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 150.

- Beckman 1998, p. 1.

- Beckman 1998, pp. 1–2.

- Westenholz 2004, p. 10.

- Beckman 1998, p. 8.

- Trémouille 2011, p. 101.

- Haas 2015, p. 374.

- George 1993, p. 59.

- George 1993, p. 99.

- Haas 2015, p. 545.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 23.

- Kümmel 1983, p. 335.

- Taracha 2009, p. 123.

- Beckman 1989, p. 99.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 66–67.

- Taracha 2009, p. 94.

- Válek 2021, p. 53.

- Beckman 1999, p. 30.

- Taracha 2009, p. 138.

- Haas 2015, p. 401.

- Cohen 1993, p. 367.

- Cohen 1993, p. 8.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 368–370.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 370–371.

- Cohen 1993, p. 373.

- Archi 2013, p. 16.

- Archi 2013, p. 18.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 76.

- Krebernik 2013, p. 201.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 65.

- Wilhelm 1989, pp. 65–66.

- Duchesne-Guillemin 1984, p. 14.

- Sharlach 2002, p. 113.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 69.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 70.

- Taracha 2009, p. 85.

- Schwemer 2022, p. 368.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 119.

- Wilhelm 1998, p. 121.

- Schwemer 2001, pp. 445–446.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 140.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 129.

- Sharlach 2002, p. 99.

- Haas 2015, p. 318.

- Wilhelm 1998, pp. 124–125.

- Wilhelm 1998, p. 125.

- Wilhelm 1998, p. 123.

- Wilhelm 1998, p. 124.

- Richter 2010, p. 510.

- Richter 2010, p. 511.

- Haas 2015, p. 136.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 61.

- Haas 2015, p. 123.

- Archi 2009, p. 214.

- Bachvarova 2013a, p. 175.

- Haas 2015, p. 106.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 41.

- Taracha 2009, p. 86.

- Wilhelm 2014a, p. 346.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 67.

- Taracha 2009, pp. 124–125.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 56.

- Archi 1990, pp. 114–115.

- Archi 1990, p. 120.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 74.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 75.

- Trémouille 2000, p. 136.

- Archi 2009, pp. 209–210.

- Beckman 2011, p. 25.

- Beckman 2005, p. 313.

- Archi 2009, p. 211.

- Polvani 2008, pp. 623–624.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 40.

- Polvani 2008, p. 620.

- Schwemer 2008, pp. 5–6.

- Beckman 2011, p. 26.

- Polvani 2008, p. 619.

- Bachvarova 2013a, p. 155.

- Beckman 2011, p. 27.

- Beckman 2011, p. 28.

- Archi 2009, p. 212.

- Beckman 2011, pp. 28–29.

- Beckman 2011, p. 29.

- Beckman 2011, p. 30.

- Beckman 2011, p. 31.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 45.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 77.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 46.

- Archi 2009, p. 217.

- Hoffner 1998, pp. 46–47.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 47.

- Archi 2009, p. 216.

- Archi 2009, p. 215.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 49.

- Hoffner 1998, pp. 49–50.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 50.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 51.

- Hoffner 1998, pp. 50–51.

- Hoffner 1998, pp. 52–53.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 55.

- Hoffner 1998, pp. 55–56.

- Haas 2015, p. 309.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 56.

- Ayali-Darshan 2015, p. 96.

- Bachvarova 2013a, p. 173.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 62.

- Bachvarova 2013a, pp. 173–174.

- Bachvarova 2013a, p. 174.

- Hoffner 1998, pp. 62–63.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 63.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 64.

- Hoffner 1998, p. 65.

- Archi 2009, p. 213.

- Archi 2009, pp. 213–214.

- Polvani 2008, p. 618.

- Rutherford 2001, p. 601.

- Rutherford 2001, pp. 599–601.

- Rutherford 2001, p. 605.

- Rutherford 2001, p. 603.

- Dijkstra 2012, p. 69.

- Ayali-Darshan 2015, p. 30.

- Rutherford 2001, p. 602.

- Archi 2013, p. 14.

- Wilhelm 2013a, p. 187.

- von Dassow 2013, p. 127.

- von Dassow 2013, p. 130.

- von Dassow 2013, p. 128.

- von Dassow 2013, p. 134.

- Wilhelm 2013a, p. 190.

- Archi 2015, p. 21.

- Wilhelm 2013a, p. 188.

- Wilhelm 2013a, pp. 188–189.

- Dijkstra 2014, p. 65.

- Dijkstra 2014, p. 67.

- Dijkstra 2014, p. 69.

- Dijkstra 2014, p. 93.

- Wilhelm 2013, pp. 417–418.

- Wilhelm 1989, p. 62.

- Taracha 2009, pp. 157–158.

- Taracha 2009, p. 158.

- Archi 2013a, p. 12.

- Archi 2009, p. 210.

- Beckman 2003, p. 52.

- Beckman 2003, p. 48.

- Archi 2004, p. 321.

- Schwemer 2022, p. 385.

- Wilhelm 1998, p. 122.

- Taracha 2009, p. 82.

- Schwemer 2022, p. 371.

- Schwemer 2022, p. 373.

- Taracha 2009, p. 92.

- Schwemer 2022, p. 386.

- Schwemer 2022, pp. 385–386.

- Schwemer 2022, p. 387.

- Pardee 2002, p. 236.

- Válek 2021, p. 49.

- van Soldt 2016, p. 97.

- van Soldt 2016, p. 102.

- van Soldt 2016, p. 103.

- van Soldt 2016, pp. 103–104.

- Válek 2021, p. 52.

- Válek 2021, pp. 49–50.

- Sharlach 2002, pp. 111–112.

- Sharlach 2002, p. 105.

- Schwemer 2001, p. 409.

- MacGinnis 2020, p. 109.

- Schwemer 2007, p. 148.

- Rutherford 2001, pp. 602–603.

- Ayali-Darshan 2015, p. 37.

Bibliography

- Archi, Alfonso (1990). "The Names of the Primeval Gods". Orientalia. GBPress - Gregorian Biblical Press. 59 (2): 114–129. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43075881. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- Archi, Alfonso (1993). "The god Ea in Anatolia". Aspects of art and iconography: Anatolia and its neighbors : studies in honor of Nimet Özgüç. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. pp. 27–33. ISBN 975-95308-0-5. OCLC 31130911.

- Archi, Alfonso (1997). "Studies in the Ebla Pantheon II". Orientalia. GBPress - Gregorian Biblical Press. 66 (4): 414–425. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43078145. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- Archi, Alfonso (2002). "Formation of the West Hurrian Pantheon: The Case of Išḫara". Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History. Penn State University Press. pp. 21–34. doi:10.1515/9781575065267-003. ISBN 9781575065267.

- Archi, Alfonso (2004). "Translation of Gods: Kumarpi, Enlil, Dagan/NISABA, Ḫalki". Orientalia. GBPress - Gregorian Biblical Press. 73 (4): 319–336. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43078173. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- Archi, Alfonso (2009). "Orality, Direct Speech and the Kumarbi Cycle". Altorientalische Forschungen. De Gruyter. 36 (2). doi:10.1524/aofo.2009.0012. ISSN 0232-8461. S2CID 162400642.

- Archi, Alfonso (2013). "The West Hurrian Pantheon and Its Background". In Collins, B. J.; Michalowski, P. (eds.). Beyond Hatti: a tribute to Gary Beckman. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. ISBN 978-1-937040-11-6. OCLC 882106763.

- Archi, Alfonso (2013a). "The Anatolian Fate-Goddesses and their Different Traditions". Diversity and Standardization. De Gruyter. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1524/9783050057576.1. ISBN 978-3-05-005756-9.

- Archi, Alfonso (2015). "A Royal Seal from Ebla (17th cent. B.C.) with Hittite Hieroglyphic Symbols". Orientalia. GBPress- Gregorian Biblical Press. 84 (1): 18–28. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 26153279. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- Ayali-Darshan, Noga (2014). "The Role of Aštabi in the Song of Ullikummi and the Eastern Mediterranean "Failed God" Stories". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. 73 (1): 95–103. doi:10.1086/674665. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 163770018.

- Ayali-Darshan, Noga (2015). "The Other Version of the Story of the Storm-god's Combat with the Sea in the Light of Egyptian, Ugaritic, and Hurro-Hittite Texts". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. Brill. 15 (1): 20–51. doi:10.1163/15692124-12341268. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Bachvarova, Mary R. (2013). "Adapting Mesopotamian Myth in Hurro-Hittite Rituals at Hattuša: IŠTAR, the Underworld, and the Legendary Kings". In Collins, B. J.; Michalowski, P. (eds.). Beyond Hatti: a tribute to Gary Beckman. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. ISBN 978-1-937040-11-6. OCLC 882106763.

- Bachvarova, Mary R. (2013a). "The Hurro-Hittite Kumarbi Cycle". Gods, heroes, and monsters: a sourcebook of Greek, Roman, and Near Eastern myths. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-064481-9. OCLC 967417697.

- Beckman, Gary (1989). "The Religion of the Hittites". The Biblical Archaeologist. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 52 (2/3): 98–108. doi:10.2307/3210202. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210202. S2CID 169554957. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

- Beckman, Gary (1998). "Ištar of Nineveh Reconsidered". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. American Schools of Oriental Research. 50: 1–10. doi:10.2307/1360026. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1360026. S2CID 163362140. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- Beckman, Gary (1999). "The Goddess Pirinkir and Her Ritual from Ḫattuša (CTH 644)". Ktèma: Civilisations de l'Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques. PERSEE Program. 24 (1): 25–39. doi:10.3406/ktema.1999.2206. hdl:2027.42/77419. ISSN 0221-5896.

- Beckman, Gary (2003). "Gilgamesh in Ḫatti". Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Penn State University Press. pp. 37–58. doi:10.1515/9781575065434-006. hdl:2027.42/77471. ISBN 9781575065434.

- Beckman, Gary (2005), "Pantheon A. II. Bei den Hethitern · Pantheon A. II. In Hittite tradition", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-06-14

- Beckman, Gary (2011). "Primordial Obstetrics. "The Song of Emergence" (CTH 344)". Hethitische Literatur: Überlieferungsprozesse, Textstrukturen, Ausdrucksformen und Nachwirken: Akten des Symposiums vom 18. bis 20. Februar 2010 in Bonn. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-063-0. OCLC 768810899.

- Cohen, Mark E. (1993). The cultic calendars of the ancient Near East. Bethesda, Md.: CDL Press. ISBN 1-883053-00-5. OCLC 27431674.

- Dijkstra, Meindert (2012). "Ishtar seduces the Sea-serpent. A New Join in the Epic of Hedammu (KUB 36, 56+95) and its meaning for the battle between Baal and Yam in Ugaritic Tradition". Ugarit-Forschungen. Band 43. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-086-9. OCLC 1101929531.

- Dijkstra, Meindert (2014). "The Hurritic Myth about Sausga of Nineveh and Hasarri (CTH 776.2)". Ugarit-Forschungen. Band 45. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-086-9. OCLC 1101929531.

- Duchesne-Guillemin, Marcelle (1984). A Hurrian Musical Score from Ugarit: The Discovery of Mesopotamian Music (PDF). Malibu, California: Undena Publications. ISBN 0-89003-158-4.

- Feliu, Lluís (2003). The god Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. Leiden Boston, MA: Brill. ISBN 90-04-13158-2. OCLC 52107444.

- Fuchs, Andreas (2005), "Tukriš", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-14

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- Haas, Volkert (2015). Geschichte der hethitischen Religion. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1: The Near and Middle East (in German). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29394-6. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

- Hoffner, Harry (1998). Hittite myths. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. ISBN 0-7885-0488-6. OCLC 39455874.

- Hoffner, Harry (2010). "The Institutional 'Poverty' of Hurrian Diviners and entanni-Women". In Cohen, Yoram; Gilan, Amir; Miller, Jared L. (eds.). Pax Hethitica: studies on the Hittites and their neighbours in honour of Itamar Singer. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-06119-3. OCLC 646006786.

- Kammenhuber, Annelies (1972), "Ḫešui, Ḫišue", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-17

- Krebernik, Manfred (2013). "Jenseitsvorstellungen in Ugarit". In Bukovec, Predrag; Kolkmann-Klamt, Barbara (eds.). Jenseitsvorstellungen im Orient (in German). Verlag Dr. Kovač. ISBN 978-3-8300-6940-9. OCLC 854347204.

- Kümmel, Hans Martin (1983), "Kummanni", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-22

- MacGinnis, John (2020). "The gods of Arbail". In Context: the Reade Festschrift. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1ddckv5.12. S2CID 234551379. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- Miller, Jared L. (2008). "Setting Up the Goddess of the Night Separately". Anatolian interfaces: Hittites, Greeks, and their neighbours: proceedings of an International Conference on Cross-cultural Interaction, September 17-19, 2004, Emory University, Atlanta, GA. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-270-4. OCLC 880878828.

- Pardee, Dennis (2002). Ritual and cult at Ugarit. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-90-04-12657-2. OCLC 558437302.

- Polvani, Anna Maria (2008). "The god Eltara and the Theogony" (PDF). Studi micenei ed egeo-anatolici. 50 (1): 617–624. ISSN 1126-6651. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate (2012). "Comments on the Translatability of Divinity: Cultic and Theological Responses to the Presence of the Other in the Ancient near East". In Bonnet, Corinne (ed.). Les représentations des dieux des autres. Caltanissetta: Sciascia. ISBN 978-88-8241-388-0. OCLC 850438175.

- Radner, Karen (2012). "Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Musasir, Kumme, Ukku and Šubria – the Buffer States between Assyria and Urartu". Biainili-Urartu: the proceedings of the symposium held in Munich 12-14 October 2007. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-2438-3. OCLC 779881614.

- Richter, Thomas (2010). "Ein Hurriter wird geboren... und benannt". In Becker, Jörg; Hempelmann, Ralph; Rehm, Ellen (eds.). Kulturlandschaft Syrien: Zentrum und Peripherie. Festschrift für Jan-Waalke Meyer (in German). Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-034-0. OCLC 587015618.

- Rutherford, Ian (2001). "The Song of the Sea (SA A-AB-BA SIR3). Thoughts on KUB 45.63". Akten des IV. Internationalen Kongresses für Hethitologie: Würzburg, 4.-8. Oktober 1999. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-04485-3. OCLC 49721937.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2001). Die Wettergottgestalten Mesopotamiens und Nordsyriens im Zeitalter der Keilschriftkulturen: Materialien und Studien nach den schriftlichen Quellen (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04456-1. OCLC 48145544.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2007). "The Storm-Gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, Synthesis, Recent Studies Part I" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. Brill. 7 (2): 121–168. doi:10.1163/156921207783876404. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2008). "The Storm-Gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, Synthesis, Recent Studies: Part II". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. Brill. 8 (1): 1–44. doi:10.1163/156921208786182428. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2022). "Religion and Power". Handbook of Hittite Empire. De Gruyter. pp. 355–418. doi:10.1515/9783110661781-009. ISBN 9783110661781.

- Sharlach, Tonia (2002). "Foreign Influences on the Religion of the Ur III Court". General studies and excavations at Nuzi 10/3. Bethesda, Md: CDL Press. ISBN 1-883053-68-4. OCLC 48399212.

- Simons, Frank (2017). "A New Join to the Hurro-Akkadian Version of the Weidner God List from Emar (Msk 74.108a + Msk 74.158k)". Altorientalische Forschungen. De Gruyter. 44 (1). doi:10.1515/aofo-2017-0009. ISSN 2196-6761. S2CID 164771112.

- Taracha, Piotr (2009). Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447058858.

- Trémouille, Marie-Claude (2000). "La religione dei Hurriti". La parola del passato: Rivista di studi antichi (in Italian). Napoli: Gaetano Macchiaroli editore. 55. ISSN 2610-8739.

- Trémouille, Marie-Claude (2011), "Šauška, Šawuška A. Philologisch", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in French), retrieved 2022-06-20

- Tugendhaft, Aaron (2016). "Gods on clay: Ancient Near Eastern scholarly practices and the history of religions". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W. (eds.). Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 164. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316226728.009.

- Válek, František (2021). "Foreigners and Religion at Ugarit". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 9 (2): 47–66. doi:10.23993/store.88230. ISSN 2323-5209.

- van Soldt, Wilfred H. (2016). "Divinities in Personal Names at Ugarit, Ras Shamra". Etudes ougaritiques IV. Paris Leuven Walpole MA: Editions recherche sur les civilisations, Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-3439-9. OCLC 51010262.

- von Dassow, Eva (2013). "Piecing Together the Song of Release". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 65: 127–162. doi:10.5615/jcunestud.65.2013.0127. ISSN 2325-6737. S2CID 163759793.

- Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (2004). "The Old Akkadian Presence in Nineveh: Fact or Fiction". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 66: 7–18. doi:10.2307/4200552. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200552. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (1982). Grundzüge der Geschichte und Kultur der Hurriter (PDF) (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3534081516. OCLC 9139063.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (1989). The Hurrians. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-442-5. OCLC 21036268.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (1998), "Name, Namengebung D. Bei den Hurritern", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-18

- Wilhelm, Gernot (2003). "König Silber und König Ḫidam". Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Penn State University Press. pp. 393–396. doi:10.1515/9781575065434-037. ISBN 9781575065434.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (2004). "Hurrian". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56256-2. OCLC 59471649.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (2013), "Takitu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-17

- Wilhelm, Gernot (2013a). "The Dispute on Manumission at Ebla: why does the Stormgod Descend to the Netherworld?". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. Presses Universitaires de France. 107: 187–191. doi:10.3917/assy.107.0187. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 42771771. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (2014), "Ullikummi", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-14

- Wilhelm, Gernot (2014a), "Unterwelt, Unterweltsgottheiten C. In Anatolien", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-06-17