Photoelectrochemical cell

A "photoelectrochemical cell" is one of two distinct classes of device. The first produces electrical energy similarly to a dye-sensitized photovoltaic cell, which meets the standard definition of a photovoltaic cell. The second is a photoelectrolytic cell, that is, a device which uses light incident on a photosensitizer, semiconductor, or aqueous metal immersed in an electrolytic solution to directly cause a chemical reaction, for example to produce hydrogen via the electrolysis of water.

Both types of device are varieties of solar cell, in that a photoelectrochemical cell's function is to use the photoelectric effect (or, very similarly, the photovoltaic effect) to convert electromagnetic radiation (typically sunlight) either directly into electrical power, or into something which can itself be easily used to produce electrical power (hydrogen, for example, can be burned to create electrical power, see photohydrogen).

Two principles

The standard photovoltaic effect, as operating in standard photovoltaic cells, involves the excitation of negative charge carriers (electrons) within a semiconductor medium, and it is negative charge carriers (free electrons) which are ultimately extracted to produce power. The classification of photoelectrochemical cells which includes Grätzel cells meets this narrow definition, albeit the charge carriers are often excitonic.

The situation within a photoelectrolytic cell, on the other hand, is quite different. For example, in a water-splitting photoelectrochemical cell, the excitation, by light, of an electron in a semiconductor leaves a hole which "draws" an electron from a neighboring water molecule:

This leaves positive charge carriers (protons, that is, H+ ions) in solution, which must then bond with one other proton and combine with two electrons in order to form hydrogen gas, according to:

A photosynthetic cell is another form of photoelectrolytic cell, with the output in that case being carbohydrates instead of molecular hydrogen.

Photoelectrolytic cell

A (water-splitting) photoelectrolytic cell electrolizes water into hydrogen and oxygen gas by irradiating the anode with electromagnetic radiation, that is, with light. This has been referred to as artificial photosynthesis and has been suggested as a way of storing solar energy in hydrogen for use as fuel.[1]

Incoming sunlight excites free electrons near the surface of the silicon electrode. These electrons flow through wires to the stainless steel electrode, where four of them react with four water molecules to form two molecules of hydrogen and 4 OH groups. The OH groups flow through the liquid electrolyte to the surface of the silicon electrode. There they react with the four holes associated with the four photoelectrons, the result being two water molecules and an oxygen molecule. Illuminated silicon immediately begins to corrode under contact with the electrolytes. The corrosion consumes material and disrupts the properties of the surfaces and interfaces within the cell.[2]

Two types of photochemical systems operate via photocatalysis. One uses semiconductor surfaces as catalysts. In these devices the semiconductor surface absorbs solar energy and acts as an electrode for water splitting. The other methodology uses in-solution metal complexes as catalysts.[3][4]

Photoelectrolytic cells have passed the 10 percent economic efficiency barrier. Corrosion of the semiconductors remains an issue, given their direct contact with water.[5] Research is now ongoing to reach a service life of 10000 hours, a requirement established by the United States Department of Energy.[6]

Other photoelectrochemical cells

The first photovoltaic cell ever designed was also the first photoelectrochemical cell. It was created in 1839, by Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel, at age 19, in his father's laboratory.[7]

The mostly commonly researched modern photoelectrochemical cell in recent decades has been the Grätzel cell, although much attention has recently shifted away from this topic to perovskite solar cells, due to relatively high efficiency of the latter and the similarity in vapor assisted deposition techniques commonly used in their creation.

Dye-sensitized solar cells or Grätzel cells use dye-adsorbed highly porous nanocrystalline titanium dioxide (nc-TiO

2) to produce electrical energy.

Materials for photoelectrolytic cells

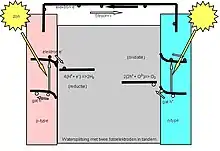

Water-splitting photoelectrochemical (PEC) cells use light energy to decompose water into hydrogen and oxygen within a two-electrode cell. In theory, three arrangements of photo-electrodes in the assembly of PECs exist:[8]

- photo-anode made of a n-type semiconductor and a metal cathode

- photo-anode made of a n-type semiconductor and a photo-cathode made of a p-type semiconductor

- photo-cathode made of a p-type semiconductor and a metal anode

There are several requirements for photoelectrode materials in PEC production:[9]

- light absorbance: determined by band gap and appropriate for solar irradiation spectrum

- charge transport: photoelectrodes must be conductive (or semi-conductive) to minimize resistive losses

- suitable band structure: large enough band gap to split water (1.23V) and appropriate positions relative to redox potentials for and

- catalytic activity: high catalytic activity increases efficiency of the water-splitting reaction

- stability: materials must be stable to prevent decomposition and loss of function

In addition to these requirements, materials must be low-cost and earth abundant for the widespread adoption of PEC water splitting to be feasible.

While the listed requirements can be applied generally, photoanodes and photocathodes have slightly different needs. A good photocathode will have early onset of the oxygen evolution reaction (low overpotential), a large photocurrent at saturation, and rapid growth of photocurrent upon onset. Good photoanodes, on the other hand, will have early onset of the hydrogen evolution reaction in addition to high current and rapid photocurrent growth. To maximize current, anode and cathode materials need to be matched together; the best anode for one cathode material may not be the best for another.

TiO

2

2

In 1967, Akira Fujishima discovered the Honda-Fujishima effect, (the photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide).

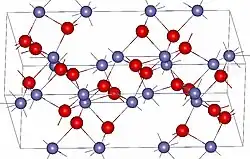

TiO

2 and other metal oxides are still most prominent[10] catalysts for efficiency reasons. Including SrTiO

3 and BaTiO

3,[11] this kind of semiconducting titanates, the conduction band has mainly titanium 3d character and the valence band oxygen 2p character. The bands are separated by a wide band gap of at least 3 eV, so that these materials absorb only UV radiation.

Change of the TiO

2 microstructure has also been investigated to further improve the performance. In 2002, Guerra (Nanoptek Corporation) discovered that high localized strain could be induced in semiconductor films formed on micro to nano-structured templates, and that this strain shifted the bandgap of the semiconductor, in the case of titanium dioxide, into the visible blue.[12] It was further found (Thulin and Guerra, 2008) that the strain also favorably shifted the band-edges to overlay the hydrogen evolution potential, and further still that the strain improved hole mobility, for lower charge recombination rate and high quantum efficiency.[13] Chandekar developed a low-cost scalable manufacturing process to produce both the nano-structured template and the strained titanium dioxide coating.[14] Other morphological investigations include TiO

2 nanowire arrays or porous nanocrystalline TiO

2 photoelectrochemical cells.[15]

GaN

GaN is another option, because metal nitrides usually have a narrow band gap that could encompass almost the entire solar spectrum.[16] GaN has a narrower band gap than TiO

2 but is still large enough to allow water splitting to occur at the surface. GaN nanowires exhibited better performance than GaN thin films, because they have a larger surface area and have a high single crystallinity which allows longer electron-hole pair lifetimes.[17] Meanwhile, other non-oxide semiconductors such as GaAs, MoS

2, WSe

2 and MoSe

2 are used as n-type electrode, due to their stability in chemical and electrochemical steps in the photocorrosion reactions.[18]

Silicon

In 2013 a cell with 2 nanometers of nickel on a silicon electrode, paired with a stainless steel electrode, immersed in an aqueous electrolyte of potassium borate and lithium borate operated for 80 hours without noticeable corrosion, versus 8 hours for titanium dioxide. In the process, about 150 ml of hydrogen gas was generated, representing the storage of about 2 kilojoules of energy.[2][19]

Structured materials

Structuring of absorbing materials has both positive and negative affects on cell performance. Structuring allows for light absorption and carrier collection to occur in different places, which loosens the requirements for pure materials and helps with catalysis. This allows for the use of non-precious and oxide catalysts that may be stable in more oxidizing conditions. However, these devices have lower open-circuit potentials which may contribute to lower performance.[20]

Hematite

Researchers have extensively investigated the use of hematite (α-Fe2O3) in PEC water-splitting devices due to its low cost, ability to be n-type doped, and band gap (2.2eV). However, performance is plagued by poor conductivity and crystal anisotropy.[21] Some researchers have enhanced catalytic activity by forming a layer of co-catalysts on the surface. Co-catalysts include cobalt-phosphate[22] and iridium oxide,[23] which is known to be a highly active catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction.[20]

Tungsten oxide

Tungsten(VI) oxide (WO3), which exhibits several different polymorphs at various temperatures, is of interest due to its high conductivity but has a relatively wide, indirect band gap (~2.7 eV) which means it cannot absorb most of the solar spectrum. Though many attempts have been made to increase absorption, they result in poor conductivity and thus WO3 does not appear to be a viable material for PEC water splitting.[20]

Bismuth vanadate

With a narrower, direct band gap (2.4 eV) and proper band alignment with water oxidation potential, the monoclinic form of BiVO

4 has garnered interest from researchers.[20] Over time, it has been shown that V-rich[24] and compact films[25] are associated with higher photocurrent, or higher performance. Bismuth Vanadate has also been studied for solar generation from seawater,[26] which is much more difficult due to the presence of contaminating ions and a more harsh corrosive environment.

Oxidation form

Photoelectrochemical oxidation (PECO) is the process by which light enables a semiconductor to promote a catalytic oxidation reaction. While a photoelectrochemical cell typically involves both a semiconductor (electrode) and a metal (counter-electrode), at sufficiently small scales, pure semiconductor particles can behave as microscopic photoelectrochemical cells. PECO has applications in the detoxification of air and water, hydrogen production, and other applications.

Reaction mechanism

The process by which a photon initiates a chemical reaction directly is known as photolysis; if this process is aided by a catalyst, it is called photocatalysis.[27] If a photon has more energy than a material's characteristic band gap, it can free an electron upon absorption by the material. The remaining, positively charged hole and the free electron may recombine, generating heat, or they can take part in photoreactions with nearby species. If the photoreactions with these species result in regeneration of the electron-donating material—i.e., if the material acts as a catalyst for the reactions—then the reactions are deemed photocatalytic. PECO represents a type of photocatalysis whereby semiconductor-based electrochemistry catalyzes an oxidation reaction—for example, the oxidative degradation of an airborne contaminant in air purification systems.

The principal objective of photoelectrocatalysis is to provide low-energy activation pathways for the passage of electronic charge carriers through the electrode electrolyte interface and, in particular, for the photoelectrochemical generation of chemical products.[28] With regard to photoelectrochemical oxidation, we may consider, for example, the following system of reactions, which constitute TiO2-catalyzed oxidation.[29]

- TiO2 (hv) → TiO2 (e− + h+)

- TiO2(h+) +RX → TiO2 + RX.+

- TiO2(h+) + H2O → TiO2 + HO. + H+

- TiO2(h+) + OH− → TiO2 + HO.

- TiO2(e−) + O2 → TiO2 + O2.−

This system shows a number of pathways for the production of oxidative species that facilitate the oxidation of the species, RX, in addition to its direct oxidation by the excited TiO2 itself. PECO concerns such a process where the electronic charge carriers are able to readily move through the reaction medium, thereby to some extent mitigating recombination reactions that would limit the oxidative process. The “photoelectrochemical cell” in this case could be as simple as a very small particle of the semiconductor catalyst. Here, on the “light” side a species is oxidized, while on the “dark” side a separate species is reduced.[30]

Photochemical oxidation (PCO) versus PECO

The classical macroscopic photoelectrochemical system consists of a semiconductor in electric contact with a counter-electrode. For N-type semiconductor particles of sufficiently small dimension, the particles polarize into anodic and cathodic regions, effectively forming microscopic photoelectrochemical cells.[28] The illuminated surface of a particle catalyzes a photooxidation reaction, while the “dark” side of the particle facilitates a concomitant reduction.[31]

Photoelectrochemical oxidation may be thought of as a special case of photochemical oxidation (PCO). Photochemical oxidation entails the generation of radical species that enable oxidation reactions, with or without the electrochemical interactions involved in semiconductor-catalyzed systems, which occur in photoelectrochemical oxidation.

Applications

PECO may be useful in treating both air and water, as well as producing hydrogen as a source of renewable energy.

Water Treatment

PECO has shown promise for water treatment of both stormwater and wastewater. Currently, water treatment methods like the use of biofiltration technologies are widely used. These technologies are effective at filtering out pollutants like suspended solids, nutrients, and heavy metals, but struggle to remove herbicides. Herbicides like diuron and atrazine are commonly used, and often end up in stormwater, posing potential health risks if they are not treated before reuse.

PECO is a useful solution to treating stormwater because of its strong oxidation capacity. Investigating different mechanisms for herbicide degradation in stormwater, like PECO, photocatalytic oxidation (PCO), and electro-catalytic oxidation (ECO), researchers determined that PECO was the best option, demonstrating complete mineralization of diuron in one hour.[32] Further research into this use for PECO is needed, as it was only able to degrade 35% of atrazine in that time, however it is a promising solution moving forward.

Air Treatment

PECO has also shown promise as a means of air purification. For people with severe allergies, air purifiers are important to protect them from allergens within their own homes.[33] However, some allergens are too small to be removed by normal purification methods. Air purifiers using PECO filters are able to remove particles as small as 0.1 nm.

These filters work as photons excite a photocatalyst, creating hydroxyl free radicals, which are extremely reactive and oxidize organic material and microorganisms that cause allergy symptoms, forming harmless products like carbon dioxide and water. Researchers testing this technology with patients suffering from allergies drew promising conclusions from their studies, observing significant reductions in total symptom scores (TSS) for both nasal (TNSS) and ocular (TOSS) allergies after just 4 weeks of using the PECO filter.[34] This research demonstrates strong potential for impactful health improvements who suffer from severe allergies and asthma.

Hydrogen Production

Possibly the most exciting potential use for PECO is producing hydrogen to be used as a source of renewable energy. Photoelectrochemical oxidation reactions that take place within PEC cells are the key to water splitting for hydrogen production. While the main concern with this technology is stability, systems that use PECO technology to create hydrogen from vapor rather than liquid water has demonstrated potential for greater stability. Early researchers working on vapor fed systems developed modules with 14% solar to hydrogen (STH) efficiency, while remaining stable for 1000+ hours.[35] More recently, further technological developments have been made, demonstrated by the direct air electrolysis (DAE) module developed by Jining Guo and his team, which produces 99% pure hydrogen from the air and has demonstrated stability of 8 months thus far.[36]

Promising research and technological advancement using PECO for different applications like water and air treatment and hydrogen production suggests that it is a valuable tool that can be utilized in a variety of ways.

History

In 1938, Goodeve and Kitchener demonstrated the “photosensitization” of TiO2—e.g., as evidenced by the fading of paints incorporating it as a pigment.[37] In 1969, Kinney and Ivanuski suggested that a variety of metal oxides, including TiO2, may catalyze the oxidation of dissolved organic materials (phenol, benzoic acid, acetic acid, sodium stearate, and sucrose) under illumination by sunlamps.[38] Additional work by Carey et al. suggested that TiO2 may be useful for the photodechlorination of PCBs.[39]

Further reading

- I. U. I. A. Gurevich, I. U. V. Pleskov, and Z. A. Rotenberg, Photoelectrochemistry. New York: Consultants Bureau, 1980.

- M. Schiavello, Photoelectrochemistry, photocatalysis, and photoreactors: Fundamentals and developments. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1985.

- A. J. Bard, M. Stratmann, and S. Licht, Encyclopedia of Electrochemistry, Volume 6, Semiconductor Electrodes and Photoelectrochemistry: Wiley, 2002.

See also

References

- John A. Turner; et al. (2007-05-17). "Photoelectrochemical Water Systems for H2 Production" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- "Silicon/nickel water splitter could lead to cheaper hydrogen". Gizmag.com. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- Berinstein, Paula (2001-06-30). Alternative energy: facts, statistics, and issues. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 1-57356-248-3.

Another photoelectrochemical method involves using dissolved metal complexes as a catalyst, which absorbs energy and creates an electric charge separation that drives the water-splitting reaction

- Deutsch, T. G.; Head, J. L.; Turner, J. A. (2008). "Photoelectrochemical Characterization and Durability Analysis of GaInPN Epilayers". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 155 (9): B903. Bibcode:2008JElS..155B.903D. doi:10.1149/1.2946478.

- Brad Plummer (2006-08-10). "A Microscopic Solution to an Enormous Problem". SLAC Today. SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- Wang, H.; Deutsch, T.; Turner, J. A. A. (2008). "Direct Water Splitting Under Visible Light with a Nanostructured Photoanode and GaInP2 Photocathode". ECS Transactions. 6 (17): 37. Bibcode:2008ECSTr...6q..37W. doi:10.1149/1.2832397. S2CID 135984508.

- "First Photovoltaic Devices". pveducation.org. Archived from the original on 2010-07-18.

- Tryk, D.; Fujishima, A; Honda, K (2000). "Recent topics in photoelectrochemistry: achievements and future prospects". Electrochimica Acta. 45 (15–16): 2363–2376. doi:10.1016/S0013-4686(00)00337-6.

- Seitz, Linsey (26 February 2019), "Lecture 13: Solar Fuels", Lecture Slides, Introduction to Electrochemistry CHE 395, Northwestern University

- A. Fujishima, K. Honda, S. Kikuchi, Kogyo Kagaku Zasshi 72 (1969) 108–113

- De Haart, L.; De Vries, A. J.; Blasse, G. (1985). "On the photoluminescence of semiconducting titanates applied in photoelectrochemical cells". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 59 (3): 291–300. Bibcode:1985JSSCh..59..291D. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(85)90296-8.

- U.S. Patent No. 7,485,799: Stress-induced bandgap-shifted semiconductor photoelectrolytic/photocatalytic/photovoltaic surface and method for making same; John M. Guerra, February 2009.

- Thulin, Lukas; Guerra, John (2008-05-14). "Calculations of strain-modified anatase ${\text{TiO}}_{2}$ band structures". Physical Review B. 77 (19): 195112. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.195112.

- U.S. Patent No.8,673,399: Bandgap-shifted semiconductor surface and method for making same, and apparatus for using same; John M. Guerra, Lukas M. Thulin, Amol N. Chandekar; March 18, 2014; assigned to Nanoptek Corp.

- Cao, F.; Oskam, G.; Meyer, G. J.; Searson, P. C. (1996). "Electron Transport in Porous Nanocrystalline TiO2 Photoelectrochemical Cells". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 100 (42): 17021–17027. doi:10.1021/jp9616573.

- Wang, D.; Pierre, A.; Kibria, M. G.; Cui, K.; Han, X.; Bevan, K. H.; Guo, H.; Paradis, S.; Hakima, A. R.; Mi, Z. (2011). "Wafer-Level Photocatalytic Water Splitting on GaN Nanowire Arrays Grown by Molecular Beam Epitaxy". Nano Letters. 11 (6): 2353–2357. Bibcode:2011NanoL..11.2353W. doi:10.1021/nl2006802. PMID 21568321.

- Hye Song Jung; Young Joon Hong; Yirui Li; Jeonghui Cho; Young-Jin Kim; Gyu-Chui Yi (2008). "Photocatalysis Using GaN Nanowires". ACS Nano. 2 (4): 637–642. doi:10.1021/nn700320y. PMID 19206593.

- Kline, G.; Kam, K.; Canfield, D.; Parkinson, B. (1981). "Efficient and stable photoelectrochemical cells constructed with WSe2 and MoSe2 photoanodes". Solar Energy Materials. 4 (3): 301–308. Bibcode:1981SoEnM...4..301K. doi:10.1016/0165-1633(81)90068-X.

- Kenney, M. J.; Gong, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Z.; Feng, J.; Lanza, M.; Dai, H. (2013). "High-Performance Silicon Photoanodes Passivated with Ultrathin Nickel Films for Water Oxidation". Science. 342 (6160): 836–840. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..836K. doi:10.1126/science.1241327. PMID 24233719. S2CID 206550249.

- Peter, Laurie; Lewerenz, Hans-Joachim (2 October 2013). Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting: Materials, Processes and Architectures. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-647-3.

- Iordanova, N.; Dupuis, M.; Rosso, K. M. (8 April 2005). "Charge transport in metal oxides: A theoretical study of hematite α-Fe2O3". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 122 (14): 144305. Bibcode:2005JChPh.122n4305I. doi:10.1063/1.1869492. PMID 15847520.

- Zhong, Diane K.; Gamelin, Daniel R. (31 March 2010). "Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation by Cobalt Catalyst ("Co−Pi")/α-FeO Composite Photoanodes: Oxygen Evolution and Resolution of a Kinetic Bottleneck". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (12): 4202–4207. doi:10.1021/ja908730h. PMID 20201513.

- Tilley, S. David; Cornuz, Maurin; Sivula, Kevin; Grätzel, Michael (23 August 2010). "Light-Induced Water Splitting with Hematite: Improved Nanostructure and Iridium Oxide Catalysis". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (36): 6405–6408. doi:10.1002/anie.201003110. PMID 20665613.

- Berglund, Sean P.; Flaherty, David W.; Hahn, Nathan T.; Bard, Allen J.; Mullins, C. Buddie (16 February 2011). "Photoelectrochemical Oxidation of Water Using Nanostructured BiVO Films". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 115 (9): 3794–3802. doi:10.1021/jp1109459.

- Su, Jinzhan; Guo, Liejin; Yoriya, Sorachon; Grimes, Craig A. (3 February 2010). "Aqueous Growth of Pyramidal-Shaped BiVO4 Nanowire Arrays and Structural Characterization: Application to Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting". Crystal Growth & Design. 10 (2): 856–861. doi:10.1021/cg9012125.

- Luo, Wenjun; Yang, Zaisan; Li, Zhaosheng; Zhang, Jiyuan; Liu, Jianguo; Zhao, Zongyan; Wang, Zhiqiang; Yan, Shicheng; Yu, Tao; Zou, Zhigang (2011). "Solar hydrogen generation from seawater with a modified BiVO4 photoanode". Energy & Environmental Science. 4 (10): 4046. doi:10.1039/C1EE01812D.

- D. Y. Goswami, Principles of solar engineering, 3rd ed. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2015.

- H. Tributsch, "Photoelectrocatalysis," in Photocatalysis: Fundamentals and Applications, N. Serpone and E. Pelizzetti, Eds., ed New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1989, pp. 339-383.

- O. Legrini, E. Oliveros, and A. Braun, "Photochemical processes for water treatment," Chemical Reviews, vol. 93, pp. 671-698, 1993.

- D. Y. Goswami, "Photoelectrochemical air disinfection " US Patent 7,063,820 B2, 2006.

- A. J. Bard, "Photoelectrochemistry and heterogeneous photo-catalysis at semiconductors," Journal of Photochemistry, vol. 10, pp. 59-75, 1979.

- Zheng, Zhaozhi; Deletic, Ana; Toe, Cui Ying; Amal, Rose; Zhang, Xiwang; Pickford, Russell; Zhou, Shujie; Zhang, Kefeng (2022-08-15). "Photo-electrochemical oxidation herbicides removal in stormwater: Degradation mechanism and pathway investigation" (PDF). Journal of Hazardous Materials. 436: 129239. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129239. ISSN 0304-3894. PMID 35739758. S2CID 249139350.

- King, Haldane (2019-08-13). "PECO v. PCO Air Purifiers: How are they different? - Molekule Blog". Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- Rao, Nikhil G.; Kumar, Ambuj; Wong, Jenny S.; Shridhar, Ravi; Goswami, Dharendra Y. (2018-06-21). "Effect of a Novel Photoelectrochemical Oxidation Air Purifier on Nasal and Ocular Allergy Symptoms". Allergy & Rhinology. 9: 2152656718781609. doi:10.1177/2152656718781609. ISSN 2152-6575. PMC 6028155. PMID 29977658.

- Kistler, Tobias A.; Um, Min Young; Agbo, Peter (2020-01-04). "Stable Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution for 1000 h at 14% Efficiency in a Monolithic Vapor-fed Device". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 167 (6): 066502. Bibcode:2020JElS..167f6502K. doi:10.1149/1945-7111/ab7d93. ISSN 0013-4651. S2CID 216411125.

- Guo, Jining; Zhang, Yuecheng; Zavabeti, Ali; Chen, Kaifei; Guo, Yalou; Hu, Guoping; Fan, Xiaolei; Li, Gang Kevin (2022-09-06). "Hydrogen production from the air". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 5046. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.5046G. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32652-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9448774. PMID 36068193.

- C. Goodeve and J. Kitchener, "Photosensitisation by titanium dioxide," Transactions of the Faraday Society, vol. 34, pp. 570–579, 1938.

- L. C. Kinney and V. R. Ivanuski, "Photolysis mechanisms for pollution abatement," 1969.

- J. H. Carey, J. Lawrence, and H. M. Tosine, "Photodechlorination of PCB's in the presence of titanium dioxide in aqueous suspensions," Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, vol. 16, pp. 697–701, 1976.