Water splitting

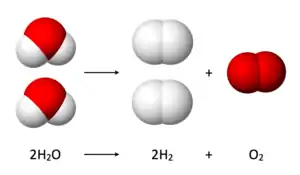

Water splitting is the chemical reaction in which water is broken down into oxygen and hydrogen:

Efficient and economical water splitting would be a technological breakthrough that could underpin a hydrogen economy, based on green hydrogen. A version of water splitting occurs in photosynthesis, but hydrogen is not produced. The reverse of water splitting is the basis of the hydrogen fuel cell.

Electrolysis

Electrolysis of water is the decomposition of water (H2O) into oxygen (O2) and hydrogen (H2) due to an electric current being passed through the water.[1]

Atmospheric electricity utilization for the chemical reaction in which water is separated into oxygen and hydrogen. (Image via: Vion, US patent 28793. June 1860.)

Atmospheric electricity utilization for the chemical reaction in which water is separated into oxygen and hydrogen. (Image via: Vion, US patent 28793. June 1860.)

- Vion, U.S. Patent 28,793, "Improved method of using atmospheric electricity", June 1860.

In power-to-gas production schemes, the excess power or off peak power created by wind generators or solar arrays is used for load balancing of the energy grid by storing and later injecting the hydrogen into the natural gas grid.

Production of hydrogen from water is energy intensive. Potential electrical energy supplies include hydropower, wind turbines, or photovoltaic cells. Usually, the electricity consumed is more valuable than the hydrogen produced so this method has not been widely used. In contrast with low-temperature electrolysis, high-temperature electrolysis (HTE) of water converts more of the initial heat energy into chemical energy (hydrogen), potentially doubling efficiency to about 50%. Because some of the energy in HTE is supplied in the form of heat, less of the energy must be converted twice (from heat to electricity, and then to chemical form), and so the process is more efficient.

Currently energy efficiency for electrolytic water splitting is 60%–70%.[2]

Water splitting in photosynthesis

A version of water splitting occurs in photosynthesis, but the electrons are shunted, not to protons, but to the electron transport chain in photosystem II. The electrons are used to convert carbon dioxide into sugars.

When photosystem I gets photo-excited, electron transfer reactions get initiated, which results in reduction of a series of electron acceptors, eventually reducing NADP+ to NADPH and PS I is oxidized. The oxidized photosystem I captures electrons from photosystem II through a series of steps involving agents like plastoquinone, cytochromes and plastocyanine. The photosystem II then brings about water oxidation resulting in evolution of oxygen, the reaction being catalyzed by CaMn4O5 clusters embedded in complex protein environment; the complex is known as oxygen evolving complex (OEC).[3][4]

In biological hydrogen production, the electrons produced by the photosystem are shunted not to a chemical synthesis apparatus but to hydrogenases, resulting in formation of H2. This biohydrogen is produced in a bioreactor.[5]

Photoelectrochemical water splitting

Using electricity produced by photovoltaic systems potentially offers the cleanest way to produce hydrogen, other than nuclear, wind, geothermal, and hydroelectric. Again, water is broken down into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis, but the electrical energy is obtained by a photoelectrochemical cell (PEC) process. The system is also named artificial photosynthesis.[6][7][8][9]

Photocatalytic water splitting

The conversion of solar energy to hydrogen by means of water splitting process is a way to achieve clean and renewable energy. This process can be more efficient if it is assisted by photocatalysts suspended directly in water rather than a photovoltaic or an electrolytic system, so that the reaction takes place in one step.[10][11]

Radiolysis

Nuclear radiation routinely breaks water bonds. In the Mponeng gold mine, South Africa, researchers found in a naturally high radiation zone a community dominated by a new phylotype of Desulfotomaculum, feeding on primarily radiolytically produced H2.[12] Spent nuclear fuel is also being investigated as a potential source of hydrogen.

Nanogalvanic aluminum alloy powder

An aluminum alloy powder invented by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory in 2017 was shown to be capable of producing hydrogen gas upon contact with water or any liquid containing water due to its unique nanoscale galvanic microstructure. It reportedly generates hydrogen at 100 percent of the theoretical yield without the need for any catalysts, chemicals, or externally supplied power.[13][14]

Thermal decomposition of water

In thermolysis, water molecules split into their atomic components hydrogen and oxygen. For example, at 2,200 °C (2,470 K; 3,990 °F) about three percent of all H2O are dissociated into various combinations of hydrogen and oxygen atoms, mostly H, H2, O, O2, and OH. Other reaction products like H2O2 or HO2 remain minor. At the very high temperature of 3,000 °C (3,270 K; 5,430 °F) more than half of the water molecules are decomposed, but at ambient temperatures only one molecule in 100 trillion dissociates by the effect of heat.[15] The high temperatures and material constraints have limited the applications of this approach.

Nuclear-thermal

One side benefit of a nuclear reactor that produces both electricity and hydrogen is that it can shift production between the two. For instance, the plant might produce electricity during the day and hydrogen at night, matching its electrical generation profile to the daily variation in demand. If the hydrogen can be produced economically, this scheme would compete favorably with existing grid energy storage schemes. What is more, there is sufficient hydrogen demand in the United States that all daily peak generation could be handled by such plants.[16]

The hybrid thermoelectric Copper-chlorine cycle is a cogeneration system using the waste heat from nuclear reactors, specifically the CANDU supercritical water reactor.[17]

Solar-thermal

The high temperatures necessary to split water can be achieved through the use of concentrating solar power. Hydrosol-2 is a 100-kilowatt pilot plant at the Plataforma Solar de Almería in Spain which uses sunlight to obtain the required 800 to 1,200 °C (1,070 to 1,470 K; 1,470 to 2,190 °F) to split water. Hydrosol II has been in operation since 2008. The design of this 100-kilowatt pilot plant is based on a modular concept. As a result, it may be possible that this technology could be readily scaled up to megawatt range by multiplying the available reactor units and by connecting the plant to heliostat fields (fields of sun-tracking mirrors) of a suitable size.[18]

Material constraints due to the required high temperatures are reduced by the design of a membrane reactor with simultaneous extraction of hydrogen and oxygen that exploits a defined thermal gradient and the fast diffusion of hydrogen. With concentrated sunlight as heat source and only water in the reaction chamber, the produced gases are very clean with the only possible contaminant being water. A "Solar Water Cracker" with a concentrator of about 100 m2 can produce almost one kilogram of hydrogen per sunshine hour.[19]

Research

Research is being conducted over photocatalysis,[20][21] the acceleration of a photoreaction in the presence of a catalyst. Its comprehension has been made possible ever since the discovery of water electrolysis by means of the titanium dioxide. Artificial photosynthesis is a research field that attempts to replicate the natural process of photosynthesis, converting sunlight, water and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates and oxygen. Recently, this has been successful in splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using an artificial compound called Nafion.[22]

High-temperature electrolysis (also HTE or steam electrolysis) is a method currently being investigated for the production of hydrogen from water with oxygen as a by-product. Other research includes thermolysis on defective carbon substrates, thus making hydrogen production possible at temperatures just under 1,000 °C (1,270 K; 1,830 °F).[23]

The iron oxide cycle is a series of thermochemical processes used to produce hydrogen. The iron oxide cycle consists of two chemical reactions whose net reactant is water and whose net products are hydrogen and oxygen. All other chemicals are recycled. The iron oxide process requires an efficient source of heat.

The sulfur–iodine cycle (S–I cycle) is a series of thermochemical processes used to produce hydrogen. The S–I cycle consists of three chemical reactions whose net reactant is water and whose net products are hydrogen and oxygen. All other chemicals are recycled. The S–I process requires an efficient source of heat.

More than 352 thermochemical cycles have been described for water splitting or thermolysis.[24] These cycles promise to produce hydrogen and oxygen from water and heat without using electricity.[25] Since all the input energy for such processes is heat, they can be more efficient than high-temperature electrolysis. This is because the efficiency of electricity production is inherently limited. Thermochemical production of hydrogen using chemical energy from coal or natural gas is generally not considered, because the direct chemical path is more efficient.

For all the thermochemical processes, the summary reaction is that of the decomposition of water:

All other reagents are recycled. None of the thermochemical hydrogen production processes have been demonstrated at production levels, although several have been demonstrated in laboratories.

There is also research into the viability of nanoparticles and catalysts to lower the temperature at which water splits.[26][27]

Recently metal–organic framework (MOF)-based materials have been shown to be a highly promising candidate for water splitting with cheap, first row transition metals.[28][29]

Research is concentrated on the following cycles:[25]

| Thermochemical cycle | LHV Efficiency | Temperature (°C/F) |

|---|---|---|

| Cerium(IV) oxide–cerium(III) oxide cycle (CeO2/Ce2O3) | ? % | 2,000 °C (3,630 °F) |

| Hybrid sulfur cycle (HyS) | 43% | 900 °C (1,650 °F) |

| Sulfur–iodine cycle (S–I cycle) | 38% | 900 °C (1,650 °F) |

| Cadmium sulfate cycle | 46% | 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) |

| Barium sulfate cycle | 39% | 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) |

| Manganese sulfate cycle | 35% | 1,100 °C (2,010 °F) |

| Zinc–zinc oxide cycle (Zn/ZnO) | 44% | 1,900 °C (3,450 °F) |

| Hybrid cadmium cycle | 42% | 1,600 °C (2,910 °F) |

| Cadmium carbonate cycle | 43% | 1,600 °C (2,910 °F) |

| Iron oxide cycle (Fe3O4/FeO) | 42% | 2,200 °C (3,990 °F) |

| Sodium manganese cycle | 49% | 1,560 °C (2,840 °F) |

| Nickel manganese ferrite cycle | 43% | 1,800 °C (3,270 °F) |

| Zinc manganese ferrite cycle | 43% | 1,800 °C (3,270 °F) |

| Copper–chlorine cycle (Cu–Cl) | 41% | 550 °C (1,022 °F) |

See also

References

- Hauch A, Ebbesen SD, Jensen SH, Mogensen M (2008). "Highly efficient high temperature electrolysis". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 18 (20): 2331. doi:10.1039/b718822f.

- Yan, Zhifei; Hitt, Jeremy L.; Turner, John A.; Mallouk, Thomas E. (9 June 2020). "Renewable electricity storage using electrolysis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (23): 12558–12563. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11712558Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1821686116. PMC 7293654. PMID 31843917.

- Yano J, Kern J, Sauer K, Latimer MJ, Pushkar Y, Biesiadka J, et al. (November 2006). "Where water is oxidized to dioxygen: structure of the photosynthetic Mn4Ca cluster". Science. 314 (5800): 821–5. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..821Y. doi:10.1126/science.1128186. PMC 3963817. PMID 17082458.

- Barber J (March 2008). "Crystal structure of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II". Inorganic Chemistry. 47 (6): 1700–10. doi:10.1021/ic701835r. PMID 18330964.

- Melis T (2008). "II.F.2 Maximizing Light Utilization Efficiency and Hydrogen Production in Microalgal Cultures" (PDF). DOE Hydrogen Program - Annual Progress Report. U.S. Department of Energy. pp. 187–190.

- Kleiner K (31 Jul 2008). "Electrode lights the way to artificial photosynthesis". New Scientist.

- Bullis K (31 Jul 2008). "Solar-Power Breakthrough. Researchers have found a cheap and easy way to store the energy made by solar power". MIT Technology Review.

- http://swegene.com/pechouse-a-proposed-cell-solar-hydrogen.html

- del Valle F, Ishikawa A, Domen K, Villoria De La Mano JA, Sánchez-Sánchez MC, González ID, et al. (2009). "Influence of Zn concentration in the activity of Cd1–xZnxS solid solutions for water splitting under visible light". Catalysis Today. 143 (1–2): 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2008.09.024.

- Navarro Yerga RM, Alvarez Galván MC, del Valle F, Villoria de la Mano JA, Fierro JL (2009). "Water Splitting on Semiconductor Catalysts under Visible-Light Irradiation". ChemSusChem. 2 (6): 471–485. doi:10.1002/cssc.200900018. PMID 19536754.

- Navarro RM, del Valle F, Villoria De La Mano JA, Álvarez-Galván MC, Fierro JL (2009). de Lasa HI, Rosales BS (eds.). Photocatalytic water splitting under visible Light: concept and materials requirements. Advances in Chemical Engineering. Vol. 36. pp. 111–143. doi:10.1016/S0065-2377(09)00404-9. ISBN 9780123747631.

- Lin LH, Wang PL, Rumble D, Lippmann-Pipke J, Boice E, Pratt LM, et al. (2006). "Long-Term Sustainability of a High-Energy, Low-Diversity Crustal Biome". Science. 314 (5798): 479–82. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..479L. doi:10.1126/science.1127376. PMID 17053150. S2CID 22420345.

- "Aluminum Based Nanogalvanic Alloys for Hydrogen Generation". U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory. Retrieved 6 Jan 2020.

- McNally D (25 Jul 2017). "Army discovery may offer new energy source". U.S. Army. Retrieved 6 Jan 2020.

- Funk JE (2001). "Thermochemical hydrogen production: past and present". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 26 (3): 185–190. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00062-8.

- Yildiz B, Petri MC, Conzelmann G, Forsberg C (2005). "Configuration and Technology Implications of Potential Nuclear Hydrogen System Applications" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. University of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 Sep 2007. Retrieved 3 Mar 2010.

- Naterer GF, Suppiah S, Lewis M, Gabriel K, Dincer I, Rosen MA, et al. (2009). "Recent Canadian Advances in Nuclear-Based Hydrogen Production and the Thermochemical Cu-Cl Cycle". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 34 (7): 2901–2917. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.01.090.

- Bürkle D, Roeb M (2008). "DLR scientists achieve solar hydrogen production in a 100-kilowatt pilotplant" (PDF). DLR - German Aerospace Center. Archived from the original on 4 Jun 2011.

- "H2 Power Systems". Archived from the original on 4 Mar 2012.

- Kudo A, Kato H, Tsuji I (2004). "Strategies for the Development of Visible-light-driven Photocatalysts for Water Splitting". Chemistry Letters. 33 (12): 1534–1539. doi:10.1246/cl.2004.1534.

- Chu S, Li W, Hamann T, Shih I, Wang D, Mi Z (2017). "Roadmap on solar water splitting: current status and future prospects". Nano Futures. 1 (2): 022001. Bibcode:2017NanoF...1b2001C. doi:10.1088/2399-1984/aa88a1. S2CID 3903962.

- Monash University (17 August 2008). "Monash team learns from nature to split water". EurekAlert.

- Kostov MK, Santiso EE, George AM, Gubbins KE, Nardelli MB (2005). "Dissociation of Water on Defective Carbon Substrates". Physical Review Letters. 95 (13): 136105. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95m6105K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.136105. PMID 16197155.

- Weimer A (2006). "Development of Solar-powered Thermochemical Production of Hydrogen from Water" (PDF). DOE Hydrogen Program.

- Weimer A (2005). "Development of Solar-powered Thermochemical Production of Hydrogen from Water" (PDF). DOE Hydrogen Program.

- "Nanoptek and Lightfuel". nanoptek.com. Retrieved 11 Apr 2021.

- McDermott M (31 Jul 2008). "A 'Giant Leap' for Clean Energy: Hydrogen Production Breakthrough from MIT". TreeHugger. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008.

- Nepal D, Das S (2013). "Sustained Water Oxidation by a Catalyst Cage-Isolated in a Metal-Organic Framework". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (28): 7224–7227. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.359.7383. doi:10.1002/anie.201301327. PMID 23729244.

- Hansen RE, Das S (2014). "Biomimetic di-manganese catalyst cage-isolated in a MOF: robust catalyst for water oxidation with Ce(IV), a non-O-donating oxidant". Energy & Environmental Science. 7 (1): 317–322. doi:10.1039/C3EE43040E.