Crescent honeyeater

The crescent honeyeater (Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus) is a passerine bird of the honeyeater family Meliphagidae native to southeastern Australia. A member of the genus Phylidonyris, it is most closely related to the common New Holland honeyeater (P. novaehollandiae) and the white-cheeked honeyeater (P. niger). Two subspecies are recognized, with P. p. halmaturinus restricted in range to Kangaroo Island and the Mount Lofty Ranges in South Australia.

| Crescent honeyeater | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male (above) and female (below) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Meliphagidae |

| Genus: | Phylidonyris |

| Species: | P. pyrrhopterus |

| Binomial name | |

| Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus (Latham, 1801) | |

| |

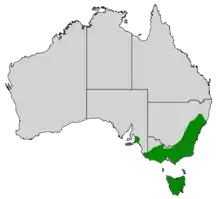

| Crescent honeyeater range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It has dark grey plumage and paler underparts, highlighted by yellow wing-patches and a broad, black crescent, outlined in white, down the sides of its breast. The species exhibits slight sexual dimorphism, with the female being duller in colour than the male. Juvenile birds are similar to the female, though the yellow wing-patches of male nestlings can be easily distinguished.

The male has a complex and variable song, which is heard throughout the year. It sings from an exposed perch, and during the breeding season performs song flights. The crescent honeyeater is found in areas of dense vegetation including sclerophyll forest and alpine habitats, as well as heathland, and parks and gardens, where its diet is made up of nectar and invertebrates. It forms long-term pairs, and often stays committed to one breeding site for several years. The female builds the nest and does most of the caring for the two to three young, which become independent within 40 days of laying its egg.

The parent birds use a range of anti-predator strategies, but nestlings can be taken by snakes, kookaburras, currawongs, or cats. While the crescent honeyeater faces a number of threats, its population numbers and distribution are sufficient for it to be listed as of Least Concern for conservation.

Taxonomy

The crescent honeyeater was originally described by ornithologist John Latham in 1801 as Certhia pyrrhoptera, because of an assumed relationship with the treecreepers Certhia.[2] It was later named Certhia australasiana by George Shaw in 1812,[3] Melithreptus melanoleucus by Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1817,[4] and Meliphaga inornata by John Gould in 1838.[5] The generic term comes from the French phylidonyre, which combines the names for a honeyeater and a sunbird (previously thought to belong to the same family).[6] The specific epithet is derived from the Ancient Greek stems pyrrhos meaning 'fire' and pteron meaning 'wing', in reference to the yellow wing patches.[7] Some guidebooks have the binomial name written as Phylidonyris pyrrhoptera;[8] however, a review in 2001 ruled that the genus name was masculine, hence pyrrhopterus is the correct specific name.[9] Two subspecies are recognised: the nominate form P. p. pyrrhopterus over most of its range; and P. p. halmaturinus, which is restricted to Kangaroo Island and the Mount Lofty Ranges.[6]

A 2004 molecular study showed its close relatives to be the New Holland honeyeater and the white-cheeked honeyeater, the three forming the now small genus Phylidonyris.[10] A 2017 genetic study using both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA found the white-streaked honeyeater to also lie within the clade. The ancestor of the crescent honeyeater diverged from the lineage giving rise to the white-streaked, New Holland and white-cheeked honeyeaters around 7.5 million years ago.[11] DNA analysis has shown honeyeaters to be related to the Pardalotidae (pardalotes), Acanthizidae (Australian warblers, scrubwrens, thornbills, etc.), and Maluridae (Australian fairy-wrens) in the large superfamily Meliphagoidea.[12]

"Crescent honeyeater" has been designated as the official common name for the species by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOC).[13] Other common names include chinawing, Egypt and horseshoe honeyeater.[14][15] Gould called it the Tasmanian honeyeater.[16]

Description

Appearance

The crescent honeyeater measures 14–17 centimetres (5.5–6.7 in) in length with a wingspan of 16–23 centimetres (6.3–9.1 in), and it weighs about 16 grams (0.56 oz).[6] It is sexually dimorphic with the female a paler version of the male.[17] The male is mostly dark grey, with clear yellow wing-patches; a broad black crescent, outlined in white, down the sides of the breast; and a white streak above the eye.[8] The top of the tail is black with yellow edges to the feathers forming distinctive yellow panels on the sides of the tail. White tips on the undertail are usually only visible in flight.[6] The underparts are pale brownish-grey fading to white. The female is duller, more olive-brown than grey, with duller yellow wing-patches and faded crescent-shaped markings.[8] Both sexes have dark grey legs and feet, deep ruby eyes and a long, downcurved black bill. The gape is also black.[6] Young birds are similar to the adults, though not as strongly marked,[8] and have dark grey bills, duller brown eyes, and yellow gapes.[6] Male nestlings can be distinguished by their more extensive yellow wing-patches from seven days old.[17] Moulting patterns of the species are poorly known; crescent honeyeaters appear to replace their primary flight feathers between October and January.[18]

While both subspecies have the same general appearance, the female of halmaturinus has paler plumage than the nominate race, and both male and female have a smaller wing and tail and longer bill. The halmaturinus population on Kangaroo Island has a significantly shorter wing and longer bill than the Mount Lofty population, although this size variation of an insular form is at odds with Allen's and Bergmann's rules.[6]

Vocalisation

The crescent honeyeater has a range of musical calls and songs. One study recorded chatter alarm calls similar to the New Holland honeyeater, a number of harsh monosyllabic or tri-syllabic contact calls, and complex and diverse songs.[19] The most common contact call is a loud, carrying "e-gypt",[20] while the alarm call is a sharp and rapid "chip-chip-chip".[21] The male also has a melodic song which is heard throughout the year, at any time of the day.[19] The structure of the song is complex and diverse, and includes both a descending whistle and a musical two-note call.[19] The male's song is performed from an exposed perch or within the tree canopy, and it engages in mating displays (song flights) during the breeding season.[19] When the female is on the nest and the male nearby, they utter low soft notes identified as "whisper song".[22]

Distribution and habitat

There are records of scattered populations of the crescent honeyeater on the Central Tablelands, the Mid North Coast, and in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, and it is widespread in the areas of New South Wales south of Dharug National Park and east of Bathurst. In Victoria it is widespread across an area from the NSW border south west to Wallan with scattered populations recorded further west. It is widespread in Tasmania, except in the northeastern part of the state where it is more sparsely distributed. It is restricted to sclerophyll forest in eastern South Australia,[23] where isolated populations have been recorded in the Mount Lofty Ranges and on Kangaroo Island. Local influxes have occurred outside its normal range in response to changes in habitat. Recorded population densities range from 0.3 birds per hectare (0.12/acre) near Orbost, to 8.7 pairs per hectare (3.5/acre) in Boola Boola State Forest, also in Victoria.[6]

While the crescent honeyeater occupies a wide variety of habitats including coastal heath, rainforest, wet sclerophyll forest, mountain forest, alpine woodland, damp gullies and thick tea-tree scrub, they all demonstrate its preference for dense vegetation.[6] It has been frequently recorded in wet sclerophyll forest dominated by eucalypts and with a thick mid-story and understory of shrubs such as blackwood, silver wattle, Cassinia, Prostanthera, and Correa. At higher altitudes it occurs in alpine heathlands and in woodlands of stunted eucalypt or conifers.[6]

The movements of the crescent honeyeater within its range are incompletely known. There is widespread evidence of seasonal migration to lower altitudes in cooler months, yet a proportion of the population remains sedentary.[6] Autumn and winter migration to the lowland coastal areas is seen in southern Tasmania, where it is not unusual to see it in urban parks and gardens,[24] as well as in Gippsland, and the New South Wales Central and South Coast. In the Sydney region, some birds appear to move down from the Blue Mountains to Sydney for the cooler months, yet others remain in either location for the whole year. It is only seen in alpine and subalpine areas of the Snowy Mountains in warmer snow-free months (mainly October to April). Other populations of crescent honeyeaters follow a more nomadic pattern of following food sources; this has been recorded in the Blue Mountains and parts of Victoria.[6]

Behaviour

Breeding

Crescent honeyeaters occupy territories during the breeding season of July to March, with pairs often staying on in the territory at the end of the season and committing to one breeding site for several years.[6] Banding studies have recaptured birds within metres of the nest in which they were raised, and one female was re-trapped at the banding place almost ten years later.[6] The pairs nest solitarily, or in loose colonies with nests around 10 metres (33 ft) apart. The male defends the territory, which is used both for foraging and breeding, though during the breeding season he is more active in protecting the area, and therefore much more vocal. During courtship the male performs song flights, soaring with quivering wings and continuously calling with a high piping note.[25]

The female builds the nest close to the boundary of the territory, usually near water, low in the shrubs. It is a deep, cup-shaped, bulky nest of cobweb, bark, grass, twigs, roots and other plant materials, lined with grass, down, moss, and fur.[24] The long strips of bark from stringybark or messmate trees are often used.[20] The clutch size is 2 or 3, occasionally 4. Measuring 19 millimetres (0.75 in) by 15 millimetres (0.59 in), the eggs are pale pink, sometimes buff-tinged, with lavender and chestnut splotches. The base colour is darker at the larger end.[24] The female incubates and broods the eggs, but both sexes feed the nestlings and remove faecal sacs, although the female does the majority of caring for the young. The young birds are fed insects, with flies making up much of the regurgitated material, according to one study.[25] The incubation period is 13 days, followed by a fledging period of 13 days. The parent birds feed the fledglings for around two weeks after they leave the nest, but the young do not remain long in the parents' territory.[17] The young are independent within 40 days of egg-laying.[17]

Parent birds have been observed using a range of anti-predator strategies: the female staying on the nest until almost touched; one or other of the pair performing distraction displays, fluttering wings and moving across the ground; the female flying rapidly at the intruder; and both birds giving harsh scolding calls when a kookaburra, tiger snake or currawong approached.[25] The nests of the crescent honeyeater are usually low in the shrubs, which makes them and their young vulnerable to predation by snakes and other birds; however, domestic and feral cats are the most likely predators to hunt this species.[15]

Crescent honeyeaters pair in long-term relationships that often last for the whole year; however, while they are socially monogamous, they appear to be sexually promiscuous. One study found that only 42% of the nestlings were sired by the male partner at the nest, despite paternity guards such as pairing and territorial defence.[26] The crescent honeyeaters observed exhibited a number of characteristics consistent with genetic promiscuity: sexual dimorphism, with sex-specific plumages identifiable at nestling stage; reduced male contribution to feeding and caring for the young; vigorous defence of the territory by the male; and frequent intrusions into other territories by females which were tolerated by the males holding those territories.[26]

Feeding

The crescent honeyeater is arboreal,[6] foraging mainly among the foliage and flowers in the understory and tree canopy on nectar, fruits and small insects.[27] It has been recorded eating the honeydew of psyllids, soft scale and felt scale insects.[6] It feeds primarily by probing flowers for nectar, and gleaning foliage and bark and sallying for insects.[6] While regularly observed feeding singly or in pairs, the crescent honeyeater has also been recorded moving in loose feeding flocks, and gathering in large groups at productive food sources.[6] A study in forest near Hobart in Tasmania found that the crescent honeyeater's diet was wholly composed of insects during the breeding season, while nectar was a significant component during winter. Insects consumed included moths and flies. Tree-trunks were the site of foraging around two-thirds of the time, and foliage a third. It fed on nectar as plants came into flower in the autumn and winter, and then foraged in Tasmanian blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus) during the breeding season in spring.[28] The flowering of royal grevillea (Grevillea victoriae) over summer in subalpine areas in the Snowy Mountains attracted large numbers of crescent honeyeaters.[6] It feeds intensively when sources are plentiful and, when feeding on flame heath (Astroloma conostephioides), it was recorded visiting an average of 34 flowers per minute.[27] Other plants it has been recorded visiting include a number of Banksia species,[29] waratah (Telopea),[30] tubular flowered genera including Astroloma, Epacris and Correa, mistletoes of the genus Amyema, and eucalypts in the Mount Lofty Ranges in South Australia.[27] In Bondi State Forest it was also recorded feeding at cluster-flower geebung (Persoonia confertiflora), native holly (Lomatia ilicifolia), tall shaggy-pea (Oxylobium arborescens), silver wattle (Acacia dealbata) and blackthorn (Bursaria spinosa).[6] Local differences in flower foraging patterns have been observed in South Australia; populations on Kangaroo Island forage more often at Adenanthos flowers than those in the nearby Fleurieu Peninsula, while the latter forage more often at eucalypt blooms, and at a higher diversity of plants overall.[31]

Conservation status

While the population numbers and distribution are sufficient for the crescent honeyeater to be listed as of Least Concern for conservation,[1] numbers have fluctuated significantly over the past twenty-five years and currently seem to be in decline.[6] The threats to the crescent honeyeater include habitat destruction, as the alpine forests in which it breeds are being reduced by weed infestations, severe bushfires, drought and land-clearing. The crescent honeyeater's dependence on long-term partnerships and breeding territories means that breeding success is threatened by the death of one partner or the destruction of habitual territory. The influx of birds to urban areas also places them at increased risk of accidents and predation.[15] Cats have been recorded preying on crescent honeyeaters,[6] and at least one guide urges cat owners to keep their cats in enclosures when outside the house or to provide a stimulating indoor environment for them.[15]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22704353A93964548. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22704353A93964548.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Latham, John (1801). Supplementum Indicis Ornithologici, sive Systematis Ornithologiae (in Latin). London: G. Leigh, J. & S. Sotheby. p. xxxviii.

- Shaw, George (1812). General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History. Aves. Vol. VIII. London: Kearsley, Wilkie & Robinson. p. 226.

- Vieillot, L.P. (1817). Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle, appliquée aux arts, principalement à l'Agriculture, à l'Écomomie rurale et domestique, à la Médecine, etc. Par une société de naturalistes et d'agriculteurs. Nouvelle edition (in French). Vol. 14. Paris: Déterville. p. 328.

- Gould, John (1838). A Synopsis of the Birds of Australia, and the Adjacent Islands. London: J. Gould. Part IV, Appendix p. 5.

- Higgins, P.J.; Peter, J.M.; Steele, W.K. (2001). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds: Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats. Vol. 5. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 998–1009. ISBN 0-19-553071-3.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Simpson, Ken; Day, Nicholas; Trusler, Peter (1993). Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Ringwood, Victoria: Viking O'Neil. p. 238. ISBN 0-670-90478-3.

- David, Normand; Gosselin, Michel (2002). "The Grammatical Gender of Avian Genera". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 122 (4): 257–82. ISSN 0007-1595.

- Driskell, Amy C.; Christidis, Les (2004). "Phylogeny and Evolution of the Australo-Papuan Honeyeaters (Passeriformes, Meliphagidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 31 (3): 943–60. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.017. PMID 15120392.

- Marki, Petter Z.; Jønsson, Knud A.; Irestedt, Martin; Nguyen, Jacqueline M.T.; Rahbek, Carsten; Fjeldså, Jon (2017). "Supermatrix phylogeny and biogeography of the Australasian Meliphagides radiation (Aves: Passeriformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 107: 516–29. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.021. hdl:10852/65203. PMID 28017855.

- Barker, F.Keith; Cibois, Alice; Schikler, Peter; Feinstein, Julie; Cracraft, Joel (2004). "Phylogeny and Diversification of the Largest Avian Radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (30): 11040–45. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111040B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101. PMC 503738. PMID 15263073.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2021). "Honeyeaters". World Bird List Version 11.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Pizzey, Graham; Doyle, Roy (1980) A Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Collins Publishers, Sydney. ISBN 073222436-5

- "Phylidonyris pyrrhoptera". Life in the Suburbs: promoting urban biodiversity in the ACT. The Australian National University. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- Gould, John (1865). Handbook to the Birds of Australia. London: J. Gould. p. 493.

- Clarke, Rohan H.; Clarke, Michael F. (2000). "The Breeding Biology of the Crescent Honeyeater Philydonyris pyrrhoptera at Wilson's Promontory, Victoria". Emu. 100 (2): 115–24. doi:10.1071/MU9843. S2CID 86730978.

- Ford, Hugh A. (1980). "Breeding and Moult in Honeyeaters (Aves : Meliphagidae) near Adelaide, South Australia". Australian Wildlife Research. 7 (3): 453–63. doi:10.1071/wr9800453.

- Jurisevic, Mark A.; Sanderson, Ken J. (1994). "The Vocal Repertoires of Six Honeyeater (Meliphagidae) Species from Adelaide, South Australia". Emu. 94 (3): 141–48. doi:10.1071/MU9940141.

- Dickison, D. (1926). "The Charming Crescent Honeyeater" (PDF). Emu. 26 (3): 120–21. doi:10.1071/MU926120.

- Morcombe, Michael (2000). Field Guide to Australian Birds. Brisbane: Steve Parish Publishing. pp. 264–65. ISBN 1-876282-10-X.

- Cooper, Roy P. (1960). "The Crescent Honeyeater". Australian Bird Watcher. 1: 70–76. ISSN 0045-0316.

- Ford, Hugh A.; Paton, David C. (1977). "The Comparative Ecology of Ten Species of Honeyeaters in South Australia". Austral Ecology. 2 (4): 399–407. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1977.tb01155.x.

- Beruldsen, Gordon (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs. Kenmore Hills, Queensland: self. pp. 322–23. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- Clarke, Rohan H.; Clarke, Michael F. (1999). "The Social Organization of a Sexually Dimorphic Honeyeater: the Crescent Honeyeater Philydonyris pyrrhoptera at Wilson's Promontory, Victoria". Australian Journal of Ecology. 24 (6): 644–54. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9993.1999.00990.x.

- Ewen, John G.; Ciborowski, Kate L.; Clarke, Rohan H.; Boulton, Rebecca L.; Clarke, Michael F. (2008). "Evidence of Extra-pair Paternity in Two Socially Monogamous Australian Passerines: the Crescent Honeyeater and the Yellow-faced Honeyeater". Emu. 108 (2): 133–37. doi:10.1071/MU07040. S2CID 85028730.

- Ford, Hugh A. (1977). "The Ecology of Honeyeaters in South Australia". South Australian Ornithologist. 27: 199–203. ISSN 0038-2973.

- Thomas, D.G. (1980). "Foraging of Honeyeaters in an Area of Tasmanian Sclerophyll Forest". Emu. 80 (2): 55–58. doi:10.1071/MU9800055.

- Taylor, Anne; Hopper, Stephen (1988). The Banksia Atlas. Australian Flora and Fauna Series. Vol. 8. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. pp. 98, 152, 184, 212, 214, 226. ISBN 0-644-07124-9.

- Nixon, Paul (1997) [1989]. The Waratah (2nd ed.). East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-878-6. plate 3.

- Ford, Hugh A. (1976). "The Honeyeaters of Kangaroo Island" (PDF). South Australian Ornithologist. 27: 134–38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-27.