Piarist High School (Timișoara)

Piarist High School is an architectural ensemble in Timișoara, originally intended for the high school established by the Piarist Order. The Secession-style ensemble, comprising a high school, a chapel church and a boarding school, was designed by László Székely and opened in 1909. After World War II, some faculties of the Timișoara Polytechnic School functioned here. Gerhardinum, the high school of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Timișoara, is currently operating here. The ensemble is inscribed in the list of historical monuments in Romania.[1]

| Piarist High School Gerhardinum Roman Catholic Theological High School | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | |

1 Queen Marie Square, Timișoara | |

| Coordinates | 45°45′9″N 21°13′21″E |

| Information | |

| Type | Public |

| Denomination | Roman Catholicism |

| Established | 1790 (Piarist High School) 1992 (Gerhardinum High School) |

| Authority | Ministry of National Education |

| Oversight | Roman Catholic Diocese of Timișoara |

| Principal | Ilona Jakab |

| Language | Romanian, Hungarian |

| Website | gerhardinum |

History

Piarist High School

In Central Europe, there were Piarist schools in six provinces ("ordinariates"): Austria, Bohemia-Moravia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. The first Piarist school in Transylvania was the gymnasium founded in 1717 in Bistrița. It was followed by those from Carei and Sighetu Marmației. Cluj also boasted a Piarist institution.

In Banat, the activity of monk-teachers began in 1747 when the Serbian nobleman Iacob Bibici and his wife Margareta Tomian built a church and a monastery on their estate in Sântana, which in 1750 they donated, together with the sum of 15,000 Rhenish florins, to the Piarist Order, for them to set up a gymnasium there. The gymnasium was inaugurated in 1751 with three classes: lower, middle and upper. The classes were apparently run by Bulgarian monks at first, but soon priest-teachers trained in several languages were called up here. From the very beginning classes were taught in all the languages spoken then in the empire, providing a revolutionary system for the teaching methods of the 18th century.[2] In 1772, two more classes were added, the fourth and the fifth, which, together with three classes of the primary school, formed the eight classes of education of the time.[3]: 184 1784 brings the closure of the boarding school next to the school, by order of the emperor, and in 1788 the school premises are requisitioned for the military hospital of the Timișoara garrison.[3]: 184 In the short time in Sântana, an estimated 17,000 students from all over the region attended school.[2]

According to an imperial patent of Emperor Joseph II, the order will be established in Timișoara from 1788, where shortly after arrival they will have to transform the school they ran into an eight-grade gymnasium.[4] As previously said, the Jesuits already had a church and a school in Timișoara, built in 1726, somewhere in the perimeter delimited by the north side of the Liberty Square and on the current Emanuil Ungureanu Street,[2] but the number of students was very small. In 1769 there were only 20 students in all six classes.[2] In 1778 the gymnasium was closed, after the abolition of the Jesuit Order in 1773. Franciscans from Bosnia built a Baroque church between 1733 and 1736. After the arrival of the Piarists, the activity of the Franciscans decreases, and their church becomes the property of the Piarists, who will use it until 1911, when it will be demolished, and in its place the Palace of the Credit Bank will be built next year.[3]: 185

The language of instruction was initially, for a short time, Latin. But, by a decree of Joseph II, German was imposed as the official language of the high school. From the middle of the 19th century until the end of World War I, classes were taught in Hungarian, and from 1920 the teaching system in Romanian was applied. At the beginning of the 19th century, there were few Romanian students in high school, but this situation may also be due to the fact that they were Orthodox and, by order of the Serbian patriarch Stefan Stratimirović, Orthodox students could not enroll in German schools unless they had Serbian names.[5]

In 1802, the sixth grade was added to the Piarist gymnasium, which operated in the Catholic seminary. Since 1841 it has been elevated to the rank of high school (upper gymnasium). In 1850 it became a complete high school (with eight classes).[3]: 185 At that time the high school had 12 teachers, a physics laboratory, a mineralogy collection and a herbarium. In the school year 1852–1853, the high school had 184 students, of whom 41 were Germans, 66 Hungarians, 45 Serbs, 26 Romanians, 4 Croats, and 2 Slovenes.[6] Among the high school students was the future writer Ioan Slavici, who attended the sixth and seventh grades of high school here between 1865 and 1867.[7]

The old Jesuit monastery is gradually becoming too small for the needs of the school and moving solutions are being sought. In this old building, the Popular Art School on Emanuil Ungureanu Street still operates today. But the adjoining church no longer exists. The architectural complex of the Piarist High School, existing to this day, with classrooms, boarding school, dormitory and chapel, was built between 1908 and 1909, with the ministerial authorization issued on 26 March 1907. The building project was designed by Alexander Baumgarten, a technical expert, whereas the detailed plans of the building were designed by the City Engineers' Office. The buildings were raised by the construction masters from Arnold Merbl & Co. under the supervision of the architect László Székely. The whole complex is elaborated in the Secession style, popular at that time, but with much more faded touches, resembling in some details a classicism adapted to the place.[2] The newly established school soon became an elite unit of Banat, so many students from all neighboring areas attended it. They also came here from Serbia, Slovenia, Galicia and Wallachia (for example, the sons of the Bibescu family). By 1918, 46,000 students had graduated here.[2] The lazaretto of the Wehrmacht was housed within the massive walls of this high school during World War II.[4]

Polytechnic Institute

After World War II, following the ban by the communist authorities on the activities of the monastic orders of the Roman Catholic Church, the activity of the Piarist High School ceased. In 1946, the high school and boarding school buildings were assigned to the Timișoara Polytechnic School.[8] The building on Piatra Craiului Street became the library of the Polytechnic. Only the chapel could keep its original destination.

After 1948, following its reorganization into a Polytechnic Institute, most of the newly established Faculty of Electrotechnics moved in the high school building,[8] which is why the ensemble was called Electro. Some of the laboratories of the Faculty of Chemistry also moved in the library building. In the 1970s, amid a development of electronics and computer science, the high school building became too small and the topic of building a new headquarters for the Faculty of Electrotechnics was raised; it will be put into use in 1976. Most of the Faculty of Electrotechnics is moved to the new headquarters, which is why after this date the Piarist ensemble was called Old Electro.

After 1989, the issue of returning the ensemble to the Roman Catholic Church arose. The Faculty of Electrotechnics is completely relocated to the new headquarters, so the high school building was retroceded relatively quickly in 1992. The laboratories of the Faculty of Chemistry could also be moved, as a new headquarters was built in 1982 for the Faculty of Chemistry. The library was the last to be moved; its new headquarters was inaugurated in 2014.

Gerhardinum High School

After the 1990s, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Timișoara managed to regain its school complex and established here the Gerhardinum Roman Catholic High School, after the name of Saint Gerard, the first bishop and patron saint of the diocese. Priest-teacher Petru Szabó was appointed first principal on 8 September 1992.[4] The transfer to possession was gradually made in several stages; the final handover took place in 2006. Also in 2006, a boarding school with 80 places was created in the old Piarist dormitory.[4]

The school is a state high school, which operates under the protection of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Timișoara, with teaching departments in Romanian and Hungarian. The profile of the high school is theological-humanistic. It also teaches real subjects, such as computer operator courses. Upon graduating high school, after taking an exam of professional skills, students have the right to teach religion in schools with grades I–VIII. The graduation exam of the computer operator course ensures the International Computer Driving Licence, an internationally recognized certificate.

Piarist Church

.jpg.webp)

The Piarist Church is the church of the Order of Piarist Monks, who came to Timișoara in 1788 and received the monastery of Franciscan monks and the church of St. John of Nepomuk built between 1733 and 1736 on the site of an old mosque, in turn built over a medieval Catholic church. The Piarists built a new church and school in 1909. The old church was taken over by the municipality and demolished in 1911, 261 skeletons of some personalities, monks and Austrian soldiers that defended the city during the siege of 1849 being moved from its crypt. The tomb of Johanna von Honrath, the wife of Carl von Greth, the city's commander, has been identified. Johanna von Grath was Beethoven's first love.[9]

The new church was dedicated to the Exaltation of the Holy Cross and is distinguished by eclectic and historicist elements – e.g., the false buttresses of the tower or the conical helmet of the tower. However, it is the only church in Timișoara that clearly fits into the "1900s style" – because, even at that time, neo-Gothic or neo-Romanesque were preferred for churches, being more sober and imposing. The secondary altars were ordered and executed in Munich, and the interior retains some elements from the old Franciscan church. József Ferenczy painted frescoes of the interior with scenes from the life of Joseph Calasanz, the founder of the Piarist Order in 1597.[10]

Piarists have been active after 1948, because it was considered a student church. The last Piarist in the country, Ferenc Való, lived and died here in 2005.[9] Since then, the church has been taken over by the priests of the Gerhardinum Roman Catholic Theological High School. The Holy Masses, as well as the devotions to Rita of Cascia and Anthony of Padua are celebrated here in Hungarian and Romanian.[9]

Principals

| Name | Term |

|---|---|

| Petru Szabó | 1992–1996 |

| Tibor Szeles | 1996–1998 |

| Ioan Kapor | 1998–2000 |

| Ioan Ciuraru | 2000–2001 |

| Iosif Heinrich | 2001–2004 |

| Petru Szabó | 2004–2009 |

| Ilona Jakab | 2009–present |

Notable students

- Pál Bodor (1930–2017), writer, poet, publicist and translator[11]

- Szilárd Bogdánffy (1911–1953), Roman Catholic cleric[12]

- Adalbert Boros (1908–2003), Roman Catholic cleric

- Miloš Crnjanski (1893–1977), writer and poet

- Hans Mokka (1912–1999), opera singer, actor and writer

- Mór Déchy (1851–1917), geographer

- Ferenc Herczeg (1863–1954), writer, playwright and journalist[11]

- Francesco Illy (1892–1956), entrepreneur and founder of illy[13]

- György Kurtág (b. 1926), composer and pianist[14]

- Adam Müller-Guttenbrunn (1852–1923), writer and director of Vienna Volksoper (1898–1903)

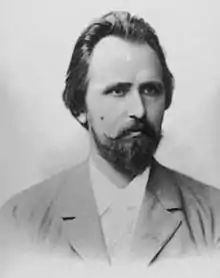

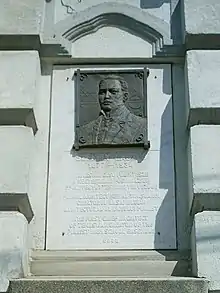

- Tivadar Ortvay (1843–1916), historian, archaeologist, geographer and Roman Catholic priest

- Ioan Slavici (1848–1925), writer and journalist[15]

References

- "Lista monumentelor istorice din județul Timiș". Direcția Județeană pentru Cultură Timiș. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- Bălan, Titus (26 June 2016). "Călugării piariști au lăsat Timișoarei una din cele mai moderne școli". Banatul Azi. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- Ilieșiu, Nicolae (2003). Timișoara: monografie istorică (2nd ed.). Timișoara: Planetarium. ISBN 973-97327-2-0.

- "Liceul Teologic Romano-Catolic Gerhardinum". Dieceza Romano-Catolică de Timișoara. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- Zamfir, Florin. "Vechimea elementului românesc în spațiul varieșean" (PDF). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-31.

- Preyer, Johann N. (1853). Monographie der königlichen Freistadt Temesvár. Timișoara: Rösch & Comp. p. 140. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- Crețu, Stănuța; et al. (1979). "Slavici, Ioan". Dicționarul literaturii române de la origini până la 1900. Bucharest: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. p. 788.

- Neguț, Nicolae (2005). Monografia Facultății de Mecanică din Timișoara: 1920-1948-2003. Timișoara: Politehnica. p. 26. ISBN 973-625-231-0.

- "Timișoara :: Biserica Piaristă". Biserici.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- Mihoc, Diana; Ciubotaru, Dan Leopold (1997). "Capela gimnaziului piarist din Timișoara – obiectiv arhitectonic "stil 1900"". Analele Banatului, Arta, SN. 2: 51–61.

- "Piaristák a Székelyföldön - Beszélgetés Kállay Emil atyával". A Magyar Piarista Diákszövetség Hírlevele. 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Boldoggá avatják a temesvári piarista diák dr. Bogdánffy Szilárd vértanú, nagyváradi segédpüspököt október 30-án". A Magyar Piarista Diákszövetség Hírlevele. 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Post mortem Temesvár díszpolgárává avatták Illy Ferenc egykori piarista öregdiákot". A Magyar Piarista Diákszövetség Hírlevele. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Jubileumi ünnepségsorozat a temesvári "Gerhardinum" Római Katolikus Teológiai Líceumban". Piarista Rend Magyar Tartománya. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- Both, Ștefan (23 April 2015). "Ioan Slavici, dezamăgit de experiența din Banat. S-a mutat la Timișoara să învețe nemțește, dar s-a trezit că trebuie să studieze tot limba maghiară". Adevărul. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.