Akimel O'odham

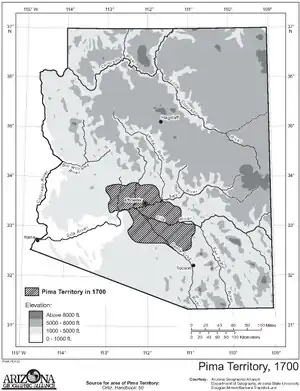

The Akimel O'odham (O'odham for "river people"), also called the Pima, are a group of Native Americans living in an area consisting of what is now central and southern Arizona, as well as northwestern Mexico in the states of Sonora and Chihuahua. The majority population of the two current bands of the Akimel O'odham in the United States are based in two reservations: the Keli Akimel Oʼodham on the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) and the On'k Akimel O'odham on the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC).

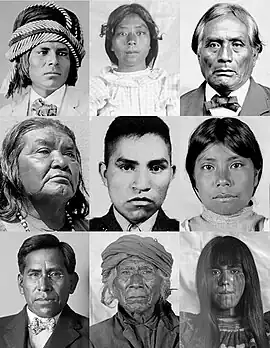

O'odham portraits | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 19,921 +/−4,574 (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| O'odham, English, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, traditional tribal religion[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Akimel O'odham are closely related to the Ak-Chin O'odham, now forming the Ak-Chin Indian Community. They are also related to the Sobaipuri, whose descendants reside on the San Xavier Indian Reservation or Wa꞉k (together with the Tohono O'odham), and in the Salt River Indian Community. Together with the related Tohono O'odham ("Desert People") and the Hia C-ed O'odham ("Sand Dune People"), the Akimel O'odham form the Upper Oʼodham or Upper Pima (also known as Pima Alto).

The short name, "Pima", is believed to have come from the phrase pi 'añi mac or pi mac, meaning "I don't know," which they used repeatedly in their initial meetings with Spanish colonists. The Spanish referred to them as the Pima.[2][3] This term was adopted by later English speakers: traders, explorers and settlers.

History prior to 1688

The Pima Indians called themselves Othama until the first account of interaction with non-Native Americans was recorded. Spanish missionaries recorded Pima villages known as Kina, Equituni and Uturituc. European Americans later corrupted the miscommunication into Pimos, which was adapted to Pima river people. The Akimel Oʼodham people today call their villages District #1 – U's kehk (Blackwater), District #2 – Hashan Kehk (Saguaro Stand), District #3 – Gu꞉U Ki (Sacaton), District #4 – Santan, District #5 – Vah Ki (Casa Blanca), District #6 – Komatke (Sierra Estrella Mountains), and District #7 – Maricopa Colony.[4]

The Akimel Oʼodham (known as the Pima to anthropologists) are a subgroup of the Upper Oʼodham or Upper Pima (also known as Pima Alto), whose lands were known in Spanish as Pimería Alta. These groups are culturally related. They are thought to be culturally descended from the group classified in archaeology as the Hohokam.[5] The term Hohokam is a derivative of the Oʼodham word Huhugam (pronounced hoo-hoo-gahm), which is literally translated as "those who have gone before," meaning "The Ancestors."

The Pima Alto or Upper Pima groups were subdivided by scholars on the basis of cultural, economic and linguistic differences into two main groupings:

One was known commonly as the Pima or River Pima. Since the late 20th century, they have been called by their own name, or endonym: Akimel Oʼotham

- Akimel O'odham (Akimel Au-Authm, meaning "River People", often simply called Pima, by outsiders, lived north of and along the Gila, the Salt, and the Santa Cruz rivers in what is today defined as Arizona)

- On'k Akimel O'odham (On'k Akimel Au-Authm – "Salt River People," lived and farmed along the Salt River), now included in the Salt River Indian Reservation.

- Keli Akimel O'otham (Keli Akimel Au-Authm, oft simply Akimel O'odham – "Gila River People", lived and farmed along the Gila River), now known as the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC)

- Ak-Chin O'odham (Ak-Chin Au-Authm),[6] Ak-Chin Indian Community

- Sobaipuri, (also simply called Sobas, called by the neighboring Akimel O'odham as Ṣáṣavino – "spotted"), originally lived in the valleys of the San Pedro River and Upper Santa Cruz River. In the early 18th century, they were gradually driven out of the lower San Pedro River valley. In the middle of the century, their remaining settlements along the upper San Pedro River were broken up by Arivaipa and Pinaleño Apache attacks. They moved west, seeking refuge among the Tohono O'odham and Akimel O'odham, with whom they merged.

The other peoples are the Tohono O'odham or Desert Pima, enrolled in the Tohono O'odham Nation.

- Tohono O'odham ("Desert People"); the neighboring Akimel O'odham called them Pahpah Au-Authm or Ba꞉bawĭkoʼa – "eating tepary beans", which was pronounced Papago by the Spanish. They lived in the semi-arid deserts and mountains south of present-day Tucson, Tubac, and south of the Gila River[7]

- Kuitatk (kúí tátk)

- Sikorhimat (sikol himadk)

- Wahw Kihk (wáw kéˑkk)

- San Pedro (wiwpul)

- Tciaur (jiawul dáhăk)

- Anegam (ʔáˑngam – "desert willow")

- Imkah (ʔiˑmiga)

- Tecolote (kolóˑdi, also cú´kud kúhūk)

- Hia C-eḍ O'odham ("Sand Dune People", also known by the neighboring O'odham as Hia Tadk Ku꞉mdam – "Sand Root Crushers,"[8] commonly known as "Sand Pimas," lived west and southwest of the Tohono O'odham in the Gran Desierto de Altar of the Sonoran Desert between the Ajo Range, the Gila River, the Colorado River and the Gulf of California south into northwestern Sonora, Mexico. There they were known to the Tohono O'odham as Uʼuva꞉k or Uʼuv Oopad, named after the Tinajas Altas Mountains.)

- Areneños Pinacateños or Pinacateños[9] (lived in the Sierra Pinacate, known as Cuk Do'ag by the Hia C-eḍ O'odham in the Cabeza Prieta Mountains in Arizona and Sonora)

- Areneños (lived in the Gran Desierto around the mountains, which were home to the Areneños Pinacateños)

The Akimel O'odham lived along the Gila, Salt, Yaqui, and Sonora rivers in ranchería-style villages. The villages were set up as a loose group of houses with familial groups sharing a central ramada and kitchen area. Brush "Olas Ki:ki" (round houses) were built around this central area. The Oʼodham are matrilocal, with daughters and their husbands living with and near the daughter's mother. Familial groups tended to consist of extended families. The Akimel Oʼodham also lived seasonally in temporary field houses in order to tend their crops.

The O'odham language, variously called O'odham ñeʼokĭ, O'odham ñiʼokĭ or Oʼotham ñiok, is spoken by all O'odham groups. There are certain dialectal differences, but they are mutually intelligible and all O'odham groups can understand one another. Lexicographical differences have arisen among the different groups, especially in reference to newer technologies and innovations.

The ancient economy of the Akimel O'odham was primarily subsistence, based on farming, hunting and gathering. They also conducted extensive trading. The prehistoric peoples built an extensive irrigation system to compensate for arid conditions.[5] It remains in use today. Over time the communities built and altered canal systems according to their changing needs.

The Akimel Oʼodham were experts in the area of textiles and produced intricate baskets as well as woven cloth. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, their primary military rivals were the Apache and Yavapai, who raided their villages at times due to competition for resources. The latter tribes were more nomadic, depending primarily on hunting and gathering, and would raid the more settled groups who cultivated foods. They established some friendly relations with the Apache.

History after 1694

Initially, the Akimel O'odham experienced little intensive colonial contact. Early encounters were limited to parties traveling through the territory or community members visiting settlements to the south. The Hispanic era (A.D.1694–1853) of the Historic period began with the first visit by Father Kino to their villages in 1694. The Pima Revolt, also known as the O'odham Uprising or the Pima Outbreak, was a revolt of Pima people in 1751 against colonial forces in Spanish Arizona and one of the major northern frontier conflicts in early New Spain.

Contact was infrequent with the Mexicans during their rule of southern Arizona between 1821 and 1853. The Akimel Oʼodham were affected by introduced European elements, such as infectious diseases to which they had no immunity, new crops (cultigens, e.g., wheat), livestock, and use of tools and goods made of metal.

Euroamerican contacts with the Akimel Oʼodham in the middle Gila Valley increased after 1846 as a result of the Mexican–American War. The Akimel Oʼodham traded and gave aid to the expeditions of Stephen Watts Kearny and Philip St. George Cooke on their way to California. After Mexico's defeat, it ceded the territory of what is now Arizona to the United States, with the exception of the land south of the Gila River. Soon thereafter the California Gold Rush began, drawing Americans to travel to California through the Mexican territory between Mesilla and the Colorado River crossings near Yuma, on what became known as the Southern Emigrant Trail. Travelers used the villages of the Akimel Oʼodham as oases to recover from the crossing of unfamiliar deserts. They also bought new supplies and livestock to support the journey across the remaining deserts to the west.

.jpg.webp)

The American era (A.D. 1853–1950), began in 1853 with the Gadsden Purchase, when the US acquired southern Arizona. New markets were developed, initially to supply immigrants heading for California. Grain was needed for horses of the Butterfield Overland Mail and for the military during the American Civil War. As a result, the Akimel Oʼodham experienced a period of prosperity. The Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) was established in 1859. The 1860 census records the Pima Villages as Agua Raiz, Arenal, Casa Blanca, Cachanillo, Cerrito, Cerro Chiquito, El Llano, and Hormiguero.[10]

After the American Civil War, numerous Euroamerican migrants came to settle upstream locations along the Gila, as well as along the lower Salt River. Due to their encroachment and competition for scarce resources, interaction between Native American groups and the Euro-American settlers became increasingly tense. The U.S. government adopted a policy of pacification and confinement of Native Americans to reservations. Uncertainty and variable crop yields led to major settlement reorganizations. The establishment of agency headquarters, churches and schools, and trading posts at Vahki (Casa Blanca) and Gu U ki (Sacaton) during the 1870s and 1880s led to the growth of these towns as administrative and commercial centers, at the expense of others.

By 1898 agriculture had nearly ceased within the GRIC. Although some Akimel Oʼodham drew rations, their principal means of livelihood was woodcutting. The first allotments of land within Gila River were established in 1914, in an attempt to break up communal land. Each individual was assigned a 10-acre (40,000 m2) parcel of irrigable land located within districts irrigated by the Santan, Agency, Blackwater, and Casa Blanca projects on the eastern half of the reservation. In 1917, the allotment size was doubled to include a primary lot of irrigable land and a secondary, usually non-contiguous 10-acre (40,000 m2) tract of grazing land.

The most ambitious effort to rectify the economic plight of the Akimel Oʼodham was the San Carlos Project Act of 1924, which authorized the construction of a water storage dam on the Gila River. It provided for the irrigation of 50,000 acres (200 km2) of Indian and 50,000 acres (200 km2) of non-Indian land. For a variety of reasons, the San Carlos Project failed to revitalize the Oʼodham farming economy. In effect the project halted the Gila river waters, and the Akimel O'odham no longer had a source of water for farming. This began the famine years. Many Oʼodham have believed these wrong and misguided government policies were an attempt of mass genocide.

Over the decades, the U.S. government promoted assimilation, forcing changes on to the Akimel Oʼodham in nearly every aspect of their lives. Since World War II, however, the Akimel Oʼodham have experienced a resurgence of interest in tribal sovereignty and economic development. The community has regained its self-government and are recognized as a tribe. In addition, they have developed several profitable enterprises in fields such as agriculture and telecommunications, and built several gaming casinos to generate revenues. They have begun to construct a water delivery system across the reservation in order to revive their farming economy.

Akimel O'odham and the Salt River

The Akimel O'odham ("River People") have lived on the banks of the Gila and Salt Rivers since long before European contact.

Their way of life (himdagĭ, sometimes rendered in English as Him-dag) was and is centered on the river, which is considered holy. The term Him-dag should be clarified, as it does not have a direct translation into the English language, and is not limited to reverence of the river. It encompasses a great deal because O'odham him-dag intertwines religion, morals, values, philosophy, and general world view which are all interconnected. Their world view/religious beliefs are centered on the natural world, and this is pervasive throughout their culture.

The Gila and Salt Rivers are currently dry, due to the (San Carlos Irrigation project) upstream dams that block the flow and the diversion of water by non-native farmers. This has been a cause of great upset among all of the Oʼodham. The upstream diversion in combination with periods of drought, led to lengthy periods of famine that were a devastating change from the documented prosperity the people had experienced until non-native settlers engaged in more aggressive farming in areas that were traditionally used by the Akimel Oʼodham and Apache in Eastern Arizona. This abuse of water rights was the impetus for a nearly century long legal battle between the Gila River Indian Community and the United States government, which was settled in favor of the Akimel Oʼodham and signed into law by George W. Bush in December 2005. As a side note, at times during the monsoon season the Salt River runs, albeit at low levels. In the weeks after December 29, 2004, when an unexpected winter rainstorm flooded areas much further upstream (in Northern Arizona), water was released through dams on the river at rates higher than at any time since the filling of Tempe Town Lake in 1998, and was a cause for minor celebration in the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. The diversion of the water and the introduction of non-native diet is said to have been the leading contributing factor in the high rate of diabetes among the Akimel Oʼodham tribe.

Modern life

As of 2014, the majority of the population lives in the federally recognized Gila River Indian Community (GRIC). In historic times a large number of Akimel O'odham migrated north to occupy the banks of the Salt River, where they formed the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC). Both tribes are confederations of two distinct ethnicities, which include the Maricopa.

Within the O'odham people, four federally recognized tribes in the Southwest speak the same language: they are called the Gila River Indian Community (Keli Akimel O'odham – "Gila River People"); the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (Onk Akimel O'odham – "Salt River People"); the Ak-Chin Indian Community (Ak-Chin O'odham); and the Tohono O'odham Nation (Tohono O'odham – "Desert People"). The remaining band, the Hia C-ed O'odham ("Sand Dune People"), are not federally recognized, but reside throughout southwestern Arizona.

Today the GRIC is a sovereign tribe residing on more than 550,000 acres (2,200 km2) of land in central Arizona. The community is divided into seven districts (similar to states) with a council representing individual subgovernments. It is self-governed by an elected Governor (currently Gregory Mendoza), Lieutenant Governor (currently Stephen Roe-Lewis) and 18-member Tribal Council. The council is elected by district with the number of electees determined by district population. There are more than 19,000 enrolled members overall.

The Gila River Indian Community is involved in various economic development enterprises that provide entertainment and recreation: three gaming casinos, associated golf courses, a luxury resort, and a western-themed amusement park. In addition, they manage various industrial parks, landfills, and construction supply. The GRIC is also involved in agriculture and runs its own farms and other agricultural projects. The Gila River Indian Reservation is home of Maricopa (Piipaa, Piipaash or Pee-Posh – "People") and Keli Akimel O'odham (also Keli Akimel Au-Authm – "Gila River People", a division of the Akimel O'odham – "River People").

The Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community is smaller in size. It also has a government of an elected President and tribal council. They operate tribal gaming, industrial projects, landfills and construction supply. The Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC) is home of the Onk Akimel O'odham (also On'k Akimel Au-Authm – "Salt River People", a division of the Akimel O'odham – "River People"), the Maricopa of Lehi (call themselves Xalychidom Piipaa or Xalychidom Piipaash – "People who live toward the water", descendants of the refugee Halchidhoma), the Tohono O'odham ("Desert People") and some Keli Akimel O'odham (also Keli Akimel Au-Authm – "Gila River People", another division of the Akimel O'odham – "River People").

The Ak-Chin Indian Community is located in the Santa Cruz Valley in Arizona. The community is composed mainly of Ak-Chin O'odham (Ak-Chin Au-Authm, also called Pima, another division of the Akimel O'odham – "River People") and Tohono O'odham, as well as some Yoeme. As of 2000, the population living in the community was 742. Ak-Chin is an O'odham word that means the "mouth of the arroyo" or "place where the wash loses itself in the sand or ground."

The Keli Akimel O'odham and the Onk Akimel O'odham have various environmentally based health issues related to the decline of their traditional economy and farming. They have the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the world, much more than is observed in other U.S. populations. While they do not have a greater risk than other tribes, the Pima people have been the subject of intensive study of diabetes, in part because they form a homogeneous group.[12]

The general increased diabetes prevalence among Native Americans has been hypothesized as the result of the interaction of genetic predisposition (the thrifty phenotype or thrifty genotype), as suggested by anthropologist Robert Ferrell in 1984[12] and a sudden shift in diet during the last century from traditional agricultural crops to processed foods, together with a decline in physical activity. For comparison, genetically similar O'odham in Mexico have only a slighter higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes than non-O'odham Mexicans.[13]

Customs

The Akimel O'odham associate great importance to the names of individuals. From age ten until the time of marriage, neither boys nor girls were allowed to speak their own names out loud. The Pima Indians believed such an act would bring bad luck to the children and their future. Similarly, people in the tribe do not say aloud the names of deceased people, in order to avoid bad luck by calling their spirits back among the living. But the word or words in the name are not dropped from the language.

The people gave their children careful oral instruction in moral, religious and other matters. Their ceremonies often included set speeches, in which the speaker would recite portions of their cosmic myth. Such a recounting was especially important in the preparation for war. These speeches were adapted for each occasion but the general context was the same.

Traditionally, the Pimas lived in a thatched wattle-and-daub hut, as seen by the early white settlers who ventured into their country:[14]

Their homes are jacales which are huts made of mats of reed-grass cut in half and built n the form of a vault on arched sticks. The top is covered with these mats, thick enough to resist the weather, Inside, they have only a petate on which to sleep, and gourds in which to carry and store water.

Notable Akimel O'odham

- Natalie Diaz, poet, language activist, former professional basketball player

- Ira Hayes (1923–1955), Marine paratrooper and flagraiser at the Battle of Iwo Jima

- Douglas Miles, artist, social worker

- Big Chief Russell Moore (1912–1983), jazz trombonist

Footnotes

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2011 American Community Survey, http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_10_1YR_B02005&prodType=table Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today

- Pritkzer, 62

- Awawtam. "Pima Stories of the Beginning of the World." The Norton Anthology of American Literature. 7th ed. Vol. A. New York: W. W. Norton &, 2007. 22–31. Print.

- About Tribe: Districts, Gila River website; accessed December 28, 2013

- Carl Waldman (2006). Encyclopedia of Native American tribes. Infobase Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8160-6274-4. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- "Ak-Chin Indian Community – About our Community". Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- Papago Local Groups and Defensive Villages, Period 1859–1890. Underhill 1939, S. 211–234.

- Gary Paul Nabhan: Gathering the Desert, University of Arizona Press, ISBN 978-0-8165-1014-6

- Because of dialect variations, both groups of the Hia C-eḍ O'odham are sometimes known as Amargosa Areneños or Amargosa Pinacateños

- The Maricopa occupied 2 others, Hueso Parado and Sacaton. John P. Wilson, Peoples of the Middle Gila: A Documentary History of the Pimas and Maricopas, 1500s–1945, Researched and Written for the Gila River Indian Community, Sacaton, Arizona, 1999, p. 166, Table 1

- "Douglas Miles." Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Apache Skateboards. (retrieved December 20, 2009)

- The Human Genome Project and Diabetes: Genetics of Type II Diabetes. New Mexico State University. 1997. June 1, 2006. "Diabetes and Genes in Disease". Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2006.

- Schulz, L.O., Bennett, P. H., Ravussin, E., Kidd, J. R., Kidd, K. K., Esparza, J., & Valencia, M. E. (2006). "Effects of traditional and western environments on prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians in Mexico and the U.S.", Diabetes Care, 29(8), 1866–1871. doi:10.2337/dc06-0138.

- Fontana, Bernard L.; Robinson, William J.; Cormack, Charles W.; Leavitt, Earnest E. (1962). Papago Indian Pottery. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press, on behalf of the American Ethnological Society. p. 6. OCLC 869680.

Further reading

- DeJong, David H (2011). Forced to abandon our fields the 1914 Clay Southworth Gila River Pima interviews. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-095-7.

- Gil-Osle, Juan Pablo. “Cabeza de Vaca’s Primahaitu Pidgin, O’odham Nation, and euskaldunak.” Journal of the Southwest 60.1 (2018): 252–68.

- Gil-Osle, Juan Pablo. “Early Map-Making of the Pimería Alta (1597–1770) in Arizona and Sonora: A Transborder Case Study.” Journal of the Southwest 63.1 (2021): 39–74.

- Ortiz, Alfonzo, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 10 Southwest. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1983.

- Pritzker, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-513877-5.

- Shaw, Anna Moore. A Pima Past. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8165-0426-1.

- Smith-Morris, Carolyn. Diabetes Among the Pima: Stories of Survival. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0816527328.

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York: Checkmark, 1999.

- Zappia, Natale A. Traders and Raiders: The Indigenous World of the Colorado Basin, 1540–1859. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.