Piracy in the Persian Gulf

Piracy in the Persian Gulf describes the naval warfare that was prevalent until the 19th century and occurred between seafaring Arabs in Eastern Arabia and the British Empire in the Persian Gulf. It was perceived as one of the primary threats to global maritime trade routes, particularly those with significance to British India and Iraq.[2][3] Many of the most notable historical instances of these raids were conducted by the Al Qasimi tribe. This led to the British mounting the Persian Gulf campaign of 1809, a major maritime action launched by the Royal Navy to bombard Ras Al Khaimah, Lingeh and other Al Qasimi ports.[2][4] The current ruler of Sharjah, Sultan bin Muhammad Al Qasimi argues in his book The Myth of Piracy in the Gulf[5] that the allegations of piracy were exaggerated by the Honourable East India Company to cut off untaxed trade routes between the Middle East and India.[6]

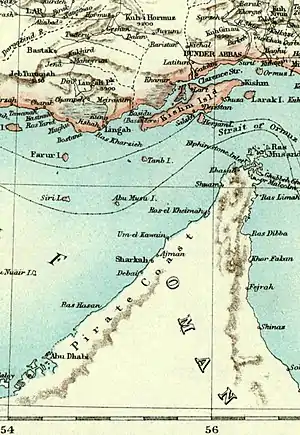

Piratical activities were common in the Persian Gulf from the late 18th century to the mid 19th century, particularly in the area known as the Pirate Coast which spanned from modern-day Qatar to Oman. Piracy was alleviated from 1820 with the signing of the General Maritime Treaty, cemented in 1853 by the Perpetual Maritime Truce, after which the Pirate Coast began to be known by the British as the Trucial Coast (present-day United Arab Emirates).[7][8]

Early history

Piracy flourished in the Persian Gulf during the commercial decline of the Dilmun Civilization (centered in present-day Bahrain) around 1800 BC.[9]

As early as 694 BC, Assyrian pirates attacked traders traversing to and from India via the Persian Gulf. King Sennacherib attempted to wipe out the piracy but his efforts were unsuccessful.[10][11]

It is suggested in the historical literature of the Chronicle of Seert that piracy interfered with the trade network of the Sasanians around the 5th century. The works mention ships en route from India being targeted for attacks along the coast of Fars during the reign of Yazdegerd II.[12]

Ibn Hawqal, a 10th-century history chronicler, alludes to piracy in the Persian Gulf in his book The Renaissance Of Islam. He describes it as such:[13]

From Ibn Hawqal's book, "The Renaissance Of Islam": —

- As early as about the year 815 the people of Basrah had undertaken an unsuccessful expedition against the pirates in Bahrain; 2 in the 10th century. People could not venture to sail the Bed Sea except with soldiers and especially artillery-men (naffatin) on board. The island Socotra in particular was regarded as a dangerous nest of pirates, at which people trembled as they passed it. It was the point d'appui of the Indian pirates who ambushed the Believers there. Piracy was never regarded as a disgraceful practice for a civilian, nor even as a curious or remarkable one. Arabic has formed no special term for it; Estakhri (p. 33) does not even call them "sea-robbers," but designates them by the far milder expression "the predatory." Otherwise the Indian term the barques is used for them.

In Richard Hodges' commentary on the increase of trade in the Persian Gulf around 825, he makes references to Bahraini pirate attacks on ships on ships from China, India and Iran. He believes the pirates were attacking ships travelling from Siraf to Basra.[14]

Marco Polo made observations of piracy in the Persian Gulf. He states that in the seventh century, the islands of Bahrain were held by the piratical tribe of Abd-ul-Kais, and in the ninth century, the seas were so disturbed that the Chinese ships navigating the Persian Gulf carried 400 to 500 armed men and supplies to beat off the pirates. Towards the end of the 13th century, Socotra was still frequented by pirates who encamped there and offered their plunder for sale.[15]

17th century

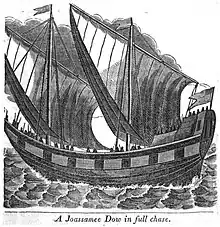

Following the expulsion of the Portuguese from Bahrain in 1602, the Al Qasimi (called by the British at the time Joasmee or Jawasmi1 ) – the tribes extending from the Qatari Peninsula to the Ras Musandam – adopted maritime raiding as a way of life due to the lack of any maritime authority in the area.[7]

European piracy in the Persian Gulf was frequent in the 16th and 17th century, targeting mainly Indian vessels en route to Mecca.[16]

Edward Balfour asserts that the Muscat Arabs were "highly predatory" from 1694 to 1736, but it was not until 1787 that the Bombay records made mention to the systemic recurrence of piracy in the Persian Gulf.[17]

The Pirate Coast

The designation Pirate Coast was first used by the British around the 17th century and acquired its name from the raiding activities that the local Arab inhabitants pursued.[18] Edward Balfour proclaims that the Pirate Coast was comprehended to have encompassed the area between Khasab and Bahrain, an area circumscribing 350 miles. It is also claimed that the principal stronghold was in Ras Al Khaimah.[8][17]

Hermann Burchardt, a 19th-century German explorer and photographer, surmised that the Pirate Coast deserved its designation, and goes on to claim that piracy was the main occupation of the inhabitants who were infamous for their fanatacism and bloodthirstiness.[8] A British customs official named John Malcolm who served in the Persian Gulf area from the 18th century to the 19th century wrote that when he questioned an Arab servant named Khudádád about the Jawasmi (the main pirate tribe in the Persian Gulf), Khudádád professed that "their occupation is piracy, and their delight murder; and to make it worse, they give you the most pious reasons for every villainy they commit".[19]

18th century

One of the earliest mentions of piracy by the British comes from a letter written by William Bowyear dated in 1767. It describes a Persian pirate named Mīr Muhannā. The letter states "In his day, he was a major source of concern for all those who traded along the Persian Gulf and his exploits were an early factor, beyond purely commercial concerns, that led the East India Company to first become entangled in the politics of the region".[20]

Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah was the most notorious pirate to have exploited the Persian Gulf during this era. He was described by the English traveller and author, James Silk Buckingham, as ‘the most successful and the most generally tolerated pirate, perhaps, that ever infest any sea.’[21] He moved to Khor Hassan in Qatar around 1785.[22] In 1810, the Wahhabis attempted to strengthen their position in the Persian Gulf region by aligning themselves with him as he was the most influential personage in Qatar at the time.[23] He ruled Qatar for a short period and the British considered him to be the leading pirate of the Pirate Coast.[24]

In his book Blood-Red Arab Flag, Charles E. Davies alleges that the issue of piracy in the Persian Gulf appeared to have escalated in 1797.[25] This date corresponds with some of the most prominent acts of piracy committed against the British by the Al Qasimi tribe, eventually giving rise to the Persian Gulf campaign of 1809.[2] The first recorded instances, however, under the rule of Saqr bin Rashid Al Qasimi are disputed as constituting acts of piracy by Emirati historians.[26]

19th century

Organized piracy under the Wahhabis

Around 1805, the Wahhabis maintained an unsteady suzerainty over parts of the southern Persian coast. They implemented a system of organized raids on foreign shipping. The vice-regent of the Pirate Coast, Husain bin Ali, compelled the Al Qasimi chiefs to send their vessels to plunder all the trade ships of the Persian Gulf without exception. He kept one-fifth of the loot for himself.[27] Arnold Wilson suggests that the Al Qasimi tribe members acted against their will so as not to incur the vengeance of the Wahhabis.[27] However, upon remarking on the rampant increase in piracy starting in 1805, J. G. Lorimer, a British chronicler, perceives this view as extreme, and believes the Al Qasimi acted within their volition.[28] With military and financial backing from the Emirate of Dir'iyah, Qasimis aimed to spread Wahhabi doctrines across the Gulf region. They had a powerful naval force and sought to end the rising European colonial infiltration on their trade and commercial routes.[29] The strategic port-city of Ras al-Khaimah, the capital of the Qawasim, offered ample opportunity for Wahhabi vessels to conduct quick, decisive attacks on British vessels from India and in the Gulf. Half of the booty captured from British ships were sent directly as tribute to the Emir of Diriyah. Throughout the 1800s, Wahhabi-Qasimi navy continually launched numerous naval attacks on British fleet and merchant ships.[30]

1809 Persian Gulf campaign

In the aftermath of a series of attacks in 1808 off the coast Sindh involving 50 Qasimi raiders and following the 1809 monsoon season, the British authorities in India decided to make a significant show of force against the Al Qasimi, in an effort not only to destroy their larger bases and as many ships as could be found, but also to counteract French encouragement of them from their embassies in Persia and Oman.[31] By the morning of 14 November, the military expedition was over and the British forces returned to their ships, having suffered light casualties of five killed and 34 wounded. Arab losses are unknown, but were probably significant, while the damage done to the Al Qasimi fleets was severe: a significant portion of their vessels had been destroyed at Ras Al Khaimah.[32]

While the British authorities claimed that acts of piracy disrupted maritime trade in the Persian Gulf, Sultan bin Muhammad Al Qasimi, author of The Myth of Piracy in the Gulf, dismisses this as an excuse used by the East India Company to further their agendas in the Persian Gulf.[6] Indian historian Sugata Bose maintains that while he believes the British allegations of piracy were self-serving, he disagrees with Al Qasimi's thesis that piracy was not widespread in the Persian Gulf region.[33] Davies argues that the motives of the Al Qasimi tribe in particular may have been misunderstood and that it cannot be definitively stated that they were pirates due to issues of semantics.[25] J.B. Kelly comments in his treatise on Britain and the Persian Gulf that the Qasimi are undeserving of their reputation as pirates, and goes on to state that it was largely earned as a result of successive naval incidents with the rulers of Muscat.[34]

Renewed tensions

There were numerous outrages expressed by the British, who were dismayed with the acts of piracy committed against them after an arrangement between them and the Al Qasimi broke down in 1815. J.G. Lorimer contends that after the dissolution of the arrangement, the Al Qasimi "now indulged in a carnival of maritime lawlessness, to which even their own previous record presented no parallel". Select instances are given:[28][35]

"In 1815 a British Indian vessel was captured by the Jawasmi near Muscat, the majority of the crew being put to death and the rest being held for ransom."

"On the 6th of January 1816, the H.E.I. Company's armed pattamar "Deriah Dowlut," manned entirely by natives of India, was attacked by Jawasmi off Dwarka, and eventually taken by boarding. Out of 38 individuals on board, 17 were killed or murdered, 8 were carried prisoners to Ras-al-Khaimah, and the remainder, being wounded, were landed on the Indian coast. The entire armament of the Deriah Dowlut consisted of two 12-pounder and three 2-pounder iron guns; whereas each of the pirate vessels, three in number, carried six 9-pounders and was manned by 100 to 200 Arabs, fully armed."

"Matters were at length brought to a head by the capture in the Red Sea, in 1816, of three Indian merchant vessels from Surat, which were making the passage to Mocha under the British flags; of the crew only a few survivors remained to tell the tale, and the pecuniary loss was estimated at Rs. 12,00,000."

Following the incident involving the Surat vessels (said to have been carried out by Amir Ibrahim, a cousin to the Al Qasimi Ruler Hassan Bin Rahmah) an investigation took place and the 'Ariel' was despatched to Ras Al Khaimah from Bushire, to where it returned with a flat denial of involvement in the affair from the Al Qasimi who were also at pains to point out they had not undertaken to recognise 'idolotrous Hindus' as British subjects, let alone anyone from the West Coast of India other than Bombay and Mangalore. A small squadron assembled off Ras Al Khaimah and, on Sheikh Hassan continuing to be 'obstinate', opened fire on four vessels anchored there. Firing from too long a range, the squadron expended some 350 rounds to no effect and disbanded, visiting other ports on the coast. Unsurprisingly given this ineffective 'punishment', Lorimer reports "The temerity of the pirates increased" and further raids on shipping followed, including the taking of "an Arab vessel but officered by Englishmen and flying English colours" just 70 miles North of Bombay.[36]

After an additional year of recurring incidents, at the end of 1818 Hassan bin Rahmah made conciliatory overtures to Bombay and was "sternly rejected." Naval resources commanded by the Al Qasimi during this period were estimated at around 60 large boats headquartered in Ras Al Khaimah, carrying from 80 to 300 men each, as well as 40 smaller vessels housed in other nearby ports.[37]

1819 Persian Gulf campaign

In 1819 the British wrote a memo regarding the issue of rising piracy in the Persian Gulf. It stated:[38]

- The piratical enterprises of the Joasmi [Al Qasimi] tribes and other Arab tribes in the Persian Gulf region had become so extensive and attended by so many atrocities on peaceful traders, that the Government of India at last determined that an expedition on a much larger and comprehensive scale than ever done before, should be undertaken for the destruction of the maritime force of these piratical tribes on the Gulf and that a new policy of bringing the tribes under British rule should be inaugurated.

The case against the Al Qasimi has been contested by the historian, author and Ruler of Sharjah, Sultan bin Muhammed Al Qasimi in his book, 'The Myth of Arab Piracy in the Gulf' in which he argues that the charges amount to a casus belli by the East India Company, which sought to limit or eliminate the 'informal' Arab trade with India, and presents a number of internal communications between the Bombay Government and its officials which shed doubt on many of the key charges made by Lorimer in his history of the affair.[26] At the time, the Chief Secretary of the Government of Bombay, F. Warden, presented a minute which laid blame for the piracy on the Wahhabi influence on the Al Qasimi and the interference of the East India Company in native affairs. Warden also, successfully, argued against a proposal to install the Sultan of Muscat as Ruler of the whole peninsula. Warden's arguments and proposals likely influenced the shape of the eventual treaty concluded with the Sheikhs of the Gulf coast.[39]

In November of that year the British embarked on an expedition against the Al Qasimi, led by Major-General William Keir Grant, voyaging to Ras Al Khaimah with a force of 3,000 soldiers. The British extended an offer to Said bin Sultan of Muscat in which he would be made ruler of the Pirate Coast if he agreed to assist the British in their expedition. Obligingly, he sent a force of 600 men and two ships.[40][41] The forces of noted pirate Rahmah ibn Jabir also assisted the British expedition.[42]

The force gathered off the coast of Ras Al Khaimah on 25 and 26 November and, on 2 and 3 December troops were landed south of the town and set up batteries of guns and mortars and, on 5 December the town was bombarded from both land and sea. Continued bombardment took place over the following four days until, on 9 December, the fortress and town of Ras Al Khaimah were stormed and found to be practically deserted. On the fall of Ras Al Khaimah, three cruisers were sent to blockade Rams to the North and this, too was found to be deserted and its inhabitants retired to the 'impregnable' hill-top fort of Dhayah.[43]

The rout of Ras Al Khaimah led to only 5 British casualties as opposed to the 400 to 1000 casualties reportedly suffered by the Al Qasimi.[44] However, the fight for Dhayah was altogether harder and hand-to-hand fighting through the date plantations of Dhayah took place between 18 and 21 December. By 21 December the Al Qasimi defenders had repaired to Dhayah Fort, protected by the slopes around the fortification. Two 24-pounder guns were brought to Dhayah from HMS Liverpool in a great effort and set up at the foot of the hill. The transport of the guns involved running them three miles up a narrow, shallow creek, dragging them through a muddy swamp, and then pulling them over rocky ground. Once they were set up, a message was sent to the defenders offering for their women and children to leave; the defenders ignored it. The guns opened fire at 8:30 AM and by 10:30 the walls of the fort were breached and its defenders put up a white flag and surrendered. Three hundred and ninety-eight fighting men and some 400 women and children left the fort.[43]

The town of Ras Al Khaimah was blown up and a garrison was established there, consisting of 800 sepoys and artillery. The expedition then visited Jazirat Al Hamra, which was deserted. The expedition then went on to destroy the fortifications and larger vessels of Umm Al Qawain, Ajman, Fasht, Sharjah, Abu Hail, and Dubai. The expedition also destroyed ten vessels that had taken shelter in Bahrain.[45]

The British took counter measures to suppress piracy in the region by relocating their troops from Ras Al Khaimah to the island of Qeshm. They eventually withdrew from the island around 1823 after protests by the Persian government.[46]

Peace treaties

.jpg.webp)

The surrender of Ras Al Khaimah and the bombardment of other coastal settlements resulted in the Sheikhs of the coast agreeing to sign treaties of peace with the British. These consisted of a number of 'preliminary agreements' (the foremost of which was that with Hassan Bin Rahmah of Ras Al Khaimah, who signed a preliminary agreement which ceded his town for use as the British Garrison) and then the General Maritime Treaty of 1820. This resulted in the area becoming known first as Trucial Oman and then generally the Trucial States.

The first article of the treaty asserts: 'There shall be a cessation of plunder and piracy by land and sea on the part of the Arabs, who are parties to this contract, for ever.' It then goes on to define piracy as being any attack that is not an action of 'acknowledged war'. The 'pacificated Arabs' agree, on land and sea, to carry a flag being a red rectangle contained within a white border of equal width to the contained rectangle, 'with or without letters on it, at their option'. This flag was to be a symbol of peace with the British government and each other.

The vessels of the 'friendly Arabs' were to carry a paper (register), signed by their chief and detailing the vessel. They should also carry a documented port clearance, which would name the 'Nacodah' (today generally spelled nakhuda), crew and number of armed men on board as well as the port of origin and destination. They would produce these on request to any British or other vessel which requested them.

The treaty also makes provision for the exchange of envoys, for the 'friendly Arabs' to act in concert against outside forces and to desist from putting people to death after they have given up their arms or to carry them off as slaves. The treaty prohibits slaving 'from the coasts of Africa or elsewhere' or the carrying of slaves in their vessels. The 'friendly Arabs', flying the agreed flag, would be free to enter, leave and trade with British ports and 'if any should attack them, the British Government will take notice of it.'[47]

Signatories

The treaty was issued in triplicate and signed at mid-day on 8 January 1820 in Ras Al Khaimah by Major-General Grant Keir together with Hassan Bin Rahmah Sheikh of 'Hatt and Falna' (hatt being the modern day village of Khatt and Falna being the modern day suburb of Ras Al Khaimah, Fahlain) and Rajib bin Ahmed, Sheikh of 'Jourat al Kamra' (Jazirah Al Hamra). A translation was prepared by Captain JP Thompson.

The treaty was then signed on 11 January 1820 in Ras Al Khaimah by Sheikh Shakbout of 'Aboo Dhebbee' (Abu Dhabi) and on 15 January by Hassan bin Ali, Sheikh of Rams and Al Dhaya (named on the treaty document as 'Sheikh of 'Zyah').

The treaty was subsequently signed in Sharjah by Saeed bin Saif of Dubai (on behalf of Mohammed bin Haza bin Zaal, the Sheikh of Dubai was in his minority) on 28 January 1820 and then in Sharjah again by Sultan bin Suggur, Sheikh of Sharjah and Ras Al Khaimah (at Falayah Fort) on 4 February 1820. On 15 March 1820 Rashid bin Humaid, Sheikh of Ajman and Abdulla bin Rashid, Sheikh of Umm Al Qawain both signed at Falayah.

Bahrain became a party to the treaty, and it was assumed that Qatar, perceived as a dependency of Bahrain by the British, was also a party to it.[48] Qatar, however, was not asked to fly the prescribed Trucial flag.[49] As punishment for alleged piracy committed by the inhabitants of Al Bidda and breach of treaty, an East India Company warships bombarded the town in 1821. The town was razed to the ground, forcing between 300 and 400 denizens of Al Bidda to flee and temporarily take shelter on the islands between the Qatar and the Trucial Coast.[50]

Further treaties

The treaty only granted protection to British vessels and did not prevent coastal wars between tribes. As a result, piratical raids continued intermittently until 1835, when the sheikhs agreed not to engage in hostilities at sea for a period of one year. The truce was renewed every year until 1853, when a treaty was signed with the United Kingdom under which the sheikhs (the Trucial Sheikhdoms) agreed to a "perpetual maritime truce".[51] As a result of this agreement, the British would in the future refer to the coastal area as the "Trucial Coast" rather than the "Pirate Coast", its earlier moniker. It was enforced by the United Kingdom, and disputes among sheikhs were referred to the British for settlement.[52] Bahrain subscribed to the treaty in 1861.[7]

Despite the treaties, piracy remained a problem until the coming of steamships capable of outrunning piratical sail ships. Much of the piracy in the late nineteenth century was triggered by religious upheavals in central Arabia.[53] In 1860, the British opted to concentrate its forces on suppressing the slave trade in adjacent East Africa. This decision left its trade vessels and steamers in the Persian Gulf vulnerable to piracy, prompting some to take their business elsewhere.[54]

During the late 19th and early 20th-century a number of changes occurred to the status of various emirates, for instance emirates such as Rams (now part of Ras Al Khaimah) were signatories to the original 1819 treaty but not recognized as trucial states, while the emirate of Fujairah, today one of the seven emirates that comprise the United Arab Emirates, was not recognised as a Trucial State until 1952. Kalba, recognized as a Trucial State by the British in 1936 is today part of the emirate of Sharjah.[55]

20th century

Kuwait signed protective treaties with Britain in 1899 and 1914 and Qatar signed a treaty in 1916.[56] These treaties, in addition to the earlier treaties signed by the Trucial States and Bahrain, were aimed suppressing piracy and slave trade in the region.[53] Acts of piracy in the Persian Gulf desisted during this period. By the 20th century, piracy had become a marginal activity,[57] mainly due to the increasingly widespread use of steamships which were too expensive for freebooters to finance.[58]

21st century

Jamie Krona of the Maritime Liaison Office declared that piracy throughout the Middle East region was not only a threat to the regional economy, but also to the global economy.[59]

Iraq experienced a rise in piracy since the start of the century. There were 70 incidents of piracy reported from June to December 2004, and 25 incidents from January to June 2005. It is usually perpetrated by small groups of three to eight people using small boats.[60] From July to October 2006, there were four reported piracy incidents in the northern Persian Gulf, which targeted mainly Iraqi fishermen.[61]

Notes

1. Al Qasimi were also referred to as Joasmi, Jawasmi, Qawasim and Qawasmi in various records and books.

References

- Al Qasimi, Muhammad (1986). The Myth of Piracy in the Arabian Gulf. UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0709921063.

- Al Qasimi, Sultan (1986). The Myth of Piracy in the Gulf. UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0709921063.

- "The Corsair - Historic Naval Fiction". historicnavalfiction.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "Sheikh Saqr bin Mohammed al-Qasimi obituary". theguardian.com. 1 November 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Al-Qasimi, Sultan Muhammed; Shāriqah), Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsimī (Ruler of (1 January 1988). The Myth of Arab Piracy in the Gulf. Routledge. ISBN 9780415029735 – via Google Books.

- Pennel, C.R. (2001). Bandits at Sea: A Pirates Reader. NYU Press. p. 11. ISBN 0814766781.

- Donaldson, Neil (2008). The Postal Agencies in Eastern Arabia and the Gulf. Lulu.com. pp. 15, 55, 73. ISBN 978-1409209423.

- Nippa, Annegret; Herbstreuth, Peter (2006). Along the Gulf : from Basra to Muscat. Schiler Hans Verlag. p. 25. ISBN 978-3899300703.

- Nyrop, Richard (2008). Area Handbook for the Persian Gulf States. Wildside Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1434462107.

- Hamilton, John (2007). A History of Pirates. Abdo Pub Co. p. 7. ISBN 978-1599287614.

- Saletore, Rajaram Narayan (1978). Indian Pirates: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Concept. p. 12.

- Larsen, Curtis (1984). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society (Prehistoric Archeology and Ecology series). University of Chicago Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0226469065.

- "Full text of "The Renaissance Of Islam"". Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Hodges, Richard (1983). Mohammed, Charlemagne, and the Origins of Europe: Archaeology and the Pirenne Thesis. Cornell University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0801492624.

- Anonymous (2010). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Volume 13, part 2. Nabu Press. p. 434. ISBN 978-1142480257.

- Cornell, Jimmy (2012). World Voyage Planner: Planning a voyage from anywhere in the world to anywhere in the world. Adlard Coles. ISBN 9781408156315.

- Edward Balfour (1885). The Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia (3rd ed.). London: B. Quaritch. pp. 189, 224–225, 367–368.

- United Arab Emirates. Infobase Publishing. 2008. p. 20. ISBN 9781438105840.

- Malcolm, John (1828). Sketches of Persia, from the journals of a traveller in the East (1st ed.). London J. Murray. p. 27.

- "A Thorn in England's Side: The Piracy of Mīr Muhannā". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Buckingham, James Silk (1829). Travels in Assyria, Media, and Persia (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 121.

- "The coming of Islam". fanack.com. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [843] (998/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Orr, Tamra (2008). Qatar (Cultures of the World). Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-0761425663.

- Davies, Charles (1997). Blood-Red Arab Flag: An Investigation Into Qasimi Piracy 1797-1820. University of Exeter Press. pp. 65–67, 91. ISBN 978-0859895095.

- al-Qāsimī, Sulṭān ibn Muḥammad (1986). The myth of Arab piracy in the Gulf. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0709921063. OCLC 12583612.

- Wilson, Arnold (2011). The Persian Gulf (RLE Iran A). Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 978-0415608497.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [653] (796/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2014. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Peterson, J. E. (2016). The Emergence of the Gulf States: Studies in Modern History. 50 Bedford Square, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-4411-3160-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Peterson, J. E. (2016). The Emergence of the Gulf States: Studies in Modern History. 50 Bedford Square, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 33, 34. ISBN 978-1-4411-3160-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 5, 1808–1811. Conway Maritime Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Marshall, John (1823). "Samuel Leslie Esq.". Royal Naval Biography. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green. pp. 88–90.

- Bose, Sugata (2009). A Hundred Horizons: The Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0674032194.

- Casey, Paula; Vine, Peter (1992). The heritage of Qatar. Immel Publishing. pp. 34.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [654] (797/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 4 August 2015. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. pp. 655–656.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [656] (799/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 26 September 2018. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "'Précis of correspondence regarding the affairs of the Persian Gulf, 1801-1853' [57r] (113/344)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2015. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Government of Bombay. pp. 659–660.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [659] (802/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Moorehead, John (1977). In Defiance of The Elements: A Personal View of Qatar. Quartet Books. p. 23. ISBN 9780704321496.

- Casey, Paula; Vine, Peter (1992). The heritage of Qatar. Immel Publishing. pp. 36.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. pp. 666–670.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [667] (810/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Lorimer, John (1915). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. British Government, Bombay. p. 669.

- Ahmadi, Kourosh (2008). Islands and International Politics in the Persian Gulf. Routledge. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0415459334.

- General Treaty for the Cessation of Plunder and Piracy by Land and Sea, Dated February 5, 1820

- Toth, Anthony. "Qatar: Historical Background." A Country Study: Qatar (Helen Chapin Metz, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 1993). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Historical references to Doha and Bidda before 1850" (PDF). The Origins of Doha Project. p. 3. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [793] (948/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Mohamed Althani, p. 22

- "UK in the UAE". Ukinuae.fco.gov.uk. 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- Leatherdale, Clive (1983). Britain and Saudi Arabia, 1925-1939: The Imperial Oasis. Routledge. pp. 10, 30. ISBN 978-0714632209.

- "Economy in Turmoil: Gulf Trade Hit By Piracy and Famine". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2005). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates : a society in transition. London: Motivate. ISBN 1860631673. OCLC 64689681.

- Ulrichsen, Kristian (2014). The First World War in the Middle East. Hurst. p. 23. ISBN 978-1849042741.

- "Global Maritime Piracy, 2008-2009". people.hofstra.edu. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Sowell, Thomas (1999). Conquests And Cultures: An International History. Basic Books. p. 39. ISBN 978-0465014002.

- "Piracy Conference Held in Oman". armedmaritimesecurity.com. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Griffes. South Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean. ProStar Publications. p. 184. ISBN 1577857992.

- "U.S. troops battling pirates, smugglers off Iraq's coast". stripes.com. 26 October 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

External links

![]() Media related to Piracy in the Persian Gulf at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Piracy in the Persian Gulf at Wikimedia Commons

- Qatar Digital Library - an online portal providing access to British Library archive materials relating to piracy in the Persian Gulf, including public domain resources